Isaac Butler’s The Method: How the Twentieth Century Learned to Act chronicles the history of Method acting and the generations of American actors shaped by it. Developed in the early 20th century by Russian actor and director Konstantin Stanislavski, the approach was refashioned in America by Lee Strasberg, Stella Adler, and Sanford Meisner — first at New York’s Group Theatre and later at the Actors Studio. This excerpt focuses on one of the Method’s later adherents, James Dean, who wasn’t exactly well respected by his fellow practitioners.

Excerpt from 'The Method'

“We now have a place, you see,” Lee Strasberg said to assembled members of the Actors Studio in October 1956. “That gives us a symbol, a feeling that it’s permanent. We don’t know what we’ll do next year, but we know where we’ll be next year. Everything is possible.” Strasberg spoke from the stage of their new home, a renovated church at 432 West 44th Street. The Actors Studio had begun as an experiment, a new way for the professional actor to work on their craft between jobs. It had weathered multiple moves, the resignation of co-founder Bobby Lewis, financial difficulties, and outside political pressure. Now it was a young institution with a permanent base of operations.

But the Studio’s triumph was tinged with grief. Only a few sentences into his benedictory address, Strasberg broke down into tears. “You see, that’s what I was afraid of,” he said and then paused for a long time. He was thinking of James Dean, who had died in an automobile accident almost exactly a year earlier. Strasberg was moved to think of Dean because Giant, his third and final film, had recently opened. “When I got in the cab, I cried. And it was funny, because actually I was crying out of two reasons. It was pleasure and enjoyment” at Dean’s performance, he said. But it was also the waste of Dean’s talent that Strasberg mourned, the way he had ruined himself with “the strange kind of behavior that not just Jimmy had, you see, but that a lot of you here have and a lot of other actors have that are going through the exact same thing … the drunkenness and the rest of it.” Strasberg could help the actor to radically investigate the self, but he didn’t know what to do with what they might find, other than recommending they see an analyst.

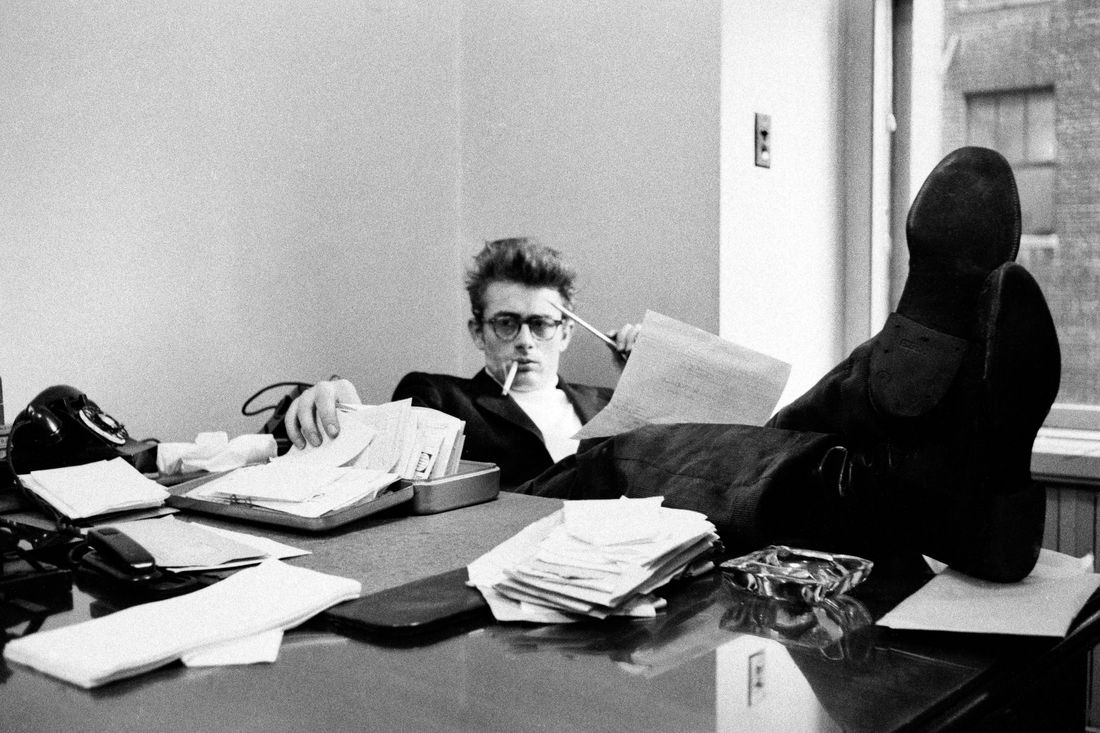

James Dean had more than his share of psychological problems. His mother, with whom he was close, died of uterine cancer when he was 9, and he was sent to live with an aunt and uncle in Indiana. As a teenager, he may have been sexually abused by his pastor. He was, in the words of Carroll Baker, “a sad-faced, introverted oddball,” and he had a pronounced, almost performative, vulnerability. Although he had dropped out of college to become an actor, he hated being exposed, analyzed, or critiqued.

Actors need to be able to adjust the thickness of their skin in order to survive, hardening themselves to the gaze of the public while becoming open and vulnerable for the sake of their work. Dean never learned how to do this, and his inability to modulate himself led to strange and off-putting behavior. Once, Lewis asked him to audition for his production of The Teahouse of the August Moon. Lewis had seen Dean’s work and felt he could do the role, but Lewis couldn’t simply cast him by fiat, particularly as the character was Japanese. “Jimmy was paralyzed with fear when I told him to prepare a few lines of Sakini’s opening monologue,” Lewis recalled. When Dean got up onstage at the Martin Beck Theatre to deliver his monologue, he collapsed in a fit of laughter and ran offstage. Lewis ran after him. What the hell was he doing?

“It’s all so embarrassing,” Dean said.

“I agree with you,” Lewis said. “But there are lots of uncomfortable things we must put up with in our work. Now pull yourself together and get this job.”

The young actor promised he would, but two lines into the speech, he started laughing again, ran offstage, and never returned. Dean was right: Garden-variety auditions are mortifying, even without having to put on a fake Japanese accent and deliver lines like “Lovely ladies, kind gentlemen, please to introduce myself. Sakini by name.” But Lewis was also right. Actors don’t get to choose their roles, and they need self-control to survive.

Many of Dean’s peers disliked him. He had a bratty streak, and his technique, such as it was, leaned heavily on his natural gifts, emphasizing spontaneity over rigor. Norma Connolly, who acted with Dean on television, said, “Jimmy was an asshole. He was also a trade kid. He would trade sexual favors to move up the ladder … he was a boring, tacky little boy.” She also remembered an Oscar party at which Dean, dressed in a T-shirt and desperate for attention, kept drumming on the host’s pots and pans and bragging about the size of his penis. Dean relented only when Marlon Brando entered the room. Dressed in a crisp suit, Brando pointed to Dean’s T-shirt and said, “That was last year, Jimmy.”

Accusations of copying Brando and Montgomery Clift dogged Dean’s brief career, in part because they were true. Dean phoned Clift regularly, trying to get the secret to his minimalist grace — the way Clift did everything just so without appearing to try too hard — but Clift refused to divulge his secrets. To study Brando’s mannerisms, Dean watched The Men again and again and read press reports about his idol’s research process. Brando, who responded to Dean’s entreaties for advice with a recommendation that the younger man see an analyst, was among those charging Dean with plagiarism. After seeing Dean in East of Eden, Brando remarked that the young actor was “wearing my last year’s wardrobe and using my last year’s talent.”

Dean responded in the press that “when a new actor comes along, he’s always compared to someone else … People were telling me I behaved like Brando before I knew who Brando was … I have my own personal rebellions and don’t have to rely on Brando’s.” But the tape tells another tale. In both East of Eden and Rebel Without a Cause, Dean copies Brando’s voice and mannerisms, sprinkling them with a tablespoon or two of Montgomery Clift. In Dean’s hands, Brando’s and Clift’s performances are distilled into stylistic tics divorced from the substance that lent them their original power. Whereas Brando’s quiet moments are alive with the character’s thoughts, Dean’s register as pouty and withdrawn. Brando could take huge emotional risks because his performances remained rooted in character. By contrast, Dean’s famous “You’re tearing me apart!” scene at the beginning of Rebel Without a Cause appears unmotivated, exploding out of nowhere for its own sake.

Elia Kazan, who directed East of Eden, had few kind words for the actor he had made into a star. He cast Dean because he felt the young man essentially was the character of Cal: a petulant, rebellious kid with emotional problems and daddy issues who was capable of both great sweetness and wild acts of self-sabotage. Once saddled with Dean, Kazan realized that he could either “get the scene right immediately, without any detailed direction … or he couldn’t get it at all.” Raymond Massey, playing Dean’s father in the film, frequently complained about his co-star’s inability to do the same thing twice or to say the lines as written. Kazan’s lack of faith in his newfound star is evident in the resulting film. For Cal’s emotional climax, Kazan hid Dean’s face in shadow, and Dean’s lines sound as if he redubbed them in postproduction.

Dean was a member of the Studio, but he rarely got up on its stage. He had been so humiliated by Strasberg’s feedback the first time he presented work there that, while he appeared in other people’s projects, he seldom risked being the focus of Strasberg’s unflinching gaze again. Dean and Strasberg had a mutually beneficial relationship in the press, however. The young man gained legitimacy as an actor through associating himself with Strasberg, whom he called “an incredible man, a walking encyclopedia, with fantastic insight.” Strasberg and the Studio gained their own legitimacy through their association with someone becoming so famous and so beloved.

The method that Dean practiced was not exactly Strasberg’s, but to the public he was a Method actor because he belonged in the stylistic lineage of John Garfield, Brando, and Clift. By imitating the actors who had come before him, he transformed the Method from an approach into a style, and his performances shifted the Method subject from adulthood to late adolescence. In all three of Dean’s films, he rebels against a father figure who is incapable of loving him properly. From the vantage point of today, all three are odd symbols of nonconformity. Cal in East of Eden wants to fit in but is incapable of doing so. Jim Stark in Rebel Without a Cause states his cause explicitly within the film: He wants his father to be a traditional, firm-handed patriarch. Jim is the enforcer of cultural norms, not their destroyer. In Giant, Dean’s best film and performance, he’s a side character, and he spends much of the film as the drunken butt of everyone’s jokes.

His raw-nerved presence reminded teenagers of all they were told to repress, his androgynous beauty summoned up their forbidden desires, and his death in a car accident immediately before Rebel Without a Cause’s premiere lent him a tragic glamour. Dean’s posthumous canonization swept the Actors Studio up into the whirlwind of youth culture despite its being an institution founded by a man in his late 40s, run by a man in his mid-50s, and built on the theories of a Russian born in the 1860s. For young actors looking to get discovered while discovering themselves, the Actors Studio was the place to be; to more respectable society gatekeepers like Hollywood gossip columnist Louella Parsons, it was “the professionally unwashed, unmannered, unconventional actors’ group.” The Actors Studio seemed to be churning out a new batch of malcontents every couple of years, actors who sneered at conformity in society, in the Hollywood studios, and in the rehearsal hall. The Method now became another form of rebellion.