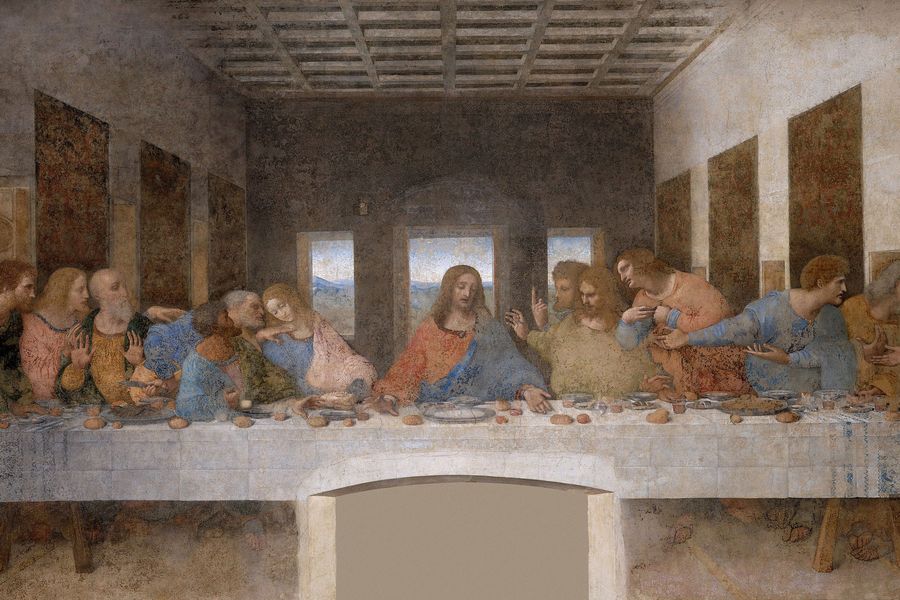

Tribulation, shock, gravitas, confusion, silent states of being, psyches agape — it is perhaps the most dramatic moment in Western history. This is the cosmic hour of despair in which Jesus announces that one of the 12 disciples gathered for the Last Supper will betray him that night and that this is the last time he will dine with them on this Earth. He bestows the Eucharist on humanity with a primitive, cannibalistic “Take, eat; this is my body”; “Drink … this is my blood.” He offers a new commandment, “Love one another,” and makes one of his apostles the new son of his mother. How is an artist to get all this into a painting?

In this time, overwhelmed and dizzied, I find myself going back to Renaissance masterworks for reasons I don’t entirely understand. Probably this has to do with feeling those paintings depict, indeed enact, momentous shifts — philosophical, stylistic, social, political, and economic — that not long before had been literally unthinkable. They are paintings in which so much is at stake. I think it also returns to the kind of painting imprinted on me as a 10-year-old really seeing art for the first time, when I became obsessed with piecing meaning together from pictures. Being a Jewish atheist in love with great stories, wanting to assimilate (even saying I was Catholic for several years), and also in love with ornate systemizations of the world and eternally curious as an outsider to the New Testament — all this makes me look for a measure of our time in those other times.

Which is how I found myself, recently, looking closely at two versions of the Last Supper. Painted just 50 years apart, in almost the same place, more than 500 years ago, they allow me to glean how ideas and worldviews can shift almost overnight. The first is the second-most-famous painting in Western art history: Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper, begun in Milan around 1495. The other is an almost unknown 1445–50 masterpiece by Andrea del Castagno in Florence, a painting Leonardo probably knew, studied, and tried to move beyond. Leonardo’s painting shattered older artistic forms and embedded new ideas in material; Castagno’s version, tremendous in its own right, can still surprise and imparts incredible spiritual power.

Really, no one has seen Leonardo’s Last Supper for half a millennium, at least as it was meant to be seen. A mad-scientist experimenter with materials and techniques, Leonardo loved blending colors, playing with shading (chiaroscuro) and smoky space (sfumato). For this showpiece, rather than employing stable fresco, he used oil and tempera paint over two coats of gesso and one or two of white lead. This promoted mold between the work and its surface. He paid it no mind. Worse, the wall he painted on was filled with moisture-retaining rubble. By the time he finished in 1498, the painting was already deteriorating. It was flaking 20 years later. In 1532, it was called “blurred and colorless.” By mid-century, it was written that “the painting is all ruined.” Vasari described it in 1556 as a “muddle of blots,” saying the figures were unrecognizable. In the 1700s, drapery was hung to protect the work. This trapped moisture between the painting and the fabric; each time the drapery was drawn, the surface was scratched more. Soon, artists began touching up missing and damaged parts. In 1770, the whole thing was largely repainted. At some point, a door was cut into the painting; floods came and went. Napoleon’s army stabled horses in the refectory, and soldiers reportedly lobbed bricks at the apostles’ heads. Finally, on August 15, 1943, the building was struck by Allied bombers and mostly destroyed: The roof was blown off. The painting survived, covered in sandbags and mattresses, but remained exposed to the elements for months. In 1999, the entire thing was “restored.” So who knows what we’re looking at?

Even so, we are struck by Leonardo’s gigantic leap of painterly faith. Unlike almost any Last Supper before it — which tended to be flatter, more grounded in symbolism and part-by-part narrative — Leonardo’s work was meant to be grasped simultaneously in a whoosh of emotion. The artist wrote that all the component parts of his work should be “seen at one and the same time both together and separately.” This is insanely advanced — it is how Vincent van Gogh wanted us to see his subject matter, surface, strokes, paint, and texture all at the same time. Leonardo’s painting has a flow of sensual space, feeling, movement, atmosphere, light, and drama — a visual-intellectual-philosophical-psychological order that hadn’t been presented or imagined on the Earth before.

This isn’t a style of the Church, Italy, a patron, or a doctrine. It’s a personal style, the work of a self-taught 40-something gay man who devised ways to dye one’s hair blond as well as build bridges. Art history has been going through regular stylistic shifts ever since. This is what a social revolution looks like.

This brings us to Castagno’s marvelous Last Supper, a Middle Renaissance masterpiece. This huge beauty covers one wall in the Florence refectory of the Benedictine nuns of Saint Apollonia. The space isn’t rhythmic, cinematic, naturalistic, breathing, or real. It’s a wildly exciting mix of Byzantine with forced geometric perspective, exaggerated horizontality, metaphysical symbolism, finicky late medievalism, spiritualism, and episodic herky-jerkiness. It shows us what Last Suppers used to look like: Each disciple might be given particular attributes to universalize them and make them recognizable; they might hold certain objects, follow established iconographic or pictorial programs, pose in specific ways.

Even if it doesn’t represent an Olympian height and will never be on a fridge magnet, I love it more than Leonardo’s. Castagno’s picture flattens like a fabulous kaleidoscopic illuminated manuscript; the overall optical effect is like seeing a hallucinogenic inlaid marble table from above. There’s no light source, windows, or central majestic Jesus, so the eye darts about this uncentered mazy space. Without having Leonardo’s unity, Castagno’s painting is about presenting a lot of information bit by bit anywhere you look. It’s a tour de force of divided attention.

Castagno’s Last Supper is set where it was in the Bible: the eastern Roman Empire city of Jerusalem. The dress is contemporary Roman: toga. The décor is wealthy contemporary Roman. Unlike Leonardo’s nondescript room, opulent materials and patterns are the visual stars of the painting — particularly six magnificent marble panels behind the disciples. Each is a lavalike abstraction of the emotional state of the disciple below. I don’t recall ever seeing anything like these before. These are each great abstract paintings. We may identify Egyptian serpentine-green porphyry (a sign of great wealth and position), cipollino rosso from nearby western Turkey, and breccia pavonazzo, among other colors.

All the apostles are scrunched together in a row on a long built-in banquette in an alcove — almost like rowers in a Roman barge. As close as they are together, however, each is in his own visual and interior space. This is important. This may be contemporary Jerusalem, but Castagno’s is a great otherworldly stage where this frozen moment is played out in a never-changing, eternal tableau. This mystic dislocation connects Castagno to the mind-set and space of Gothic and medieval art. Things don’t flow; they stop and start. Yet his scale, space, techniques, ambition, and colors are pure Renaissance. This makes optical sparks crackle. The figures are not people so much as they’re symbolic statues and states of mind. This turns a skeleton key in the picture. Now I see the disciples having visionary premonitions of all dying martyrs’ deaths.

Start with Judas, easy to spot as the only one without a halo, and in medieval style, Castagno seats him alone on the opposite side of the table. Note his hooknose and stereotypical Jewish features. Judas teeters on a three-legged stool and seems suspended in midair. His feet dangle, which makes him look silly and stunted. In the Gospel of John (the account Castagno appears to use), Peter asks Jesus to say who the traitor is. Jesus says it is he whom he offers a crust of bread. Look close; Judas holds that sop in his right hand. We don’t see his left hand, perhaps because it grips the 30 pieces of silver received for the betrayal.

Peter is seated on Jesus’ right (our left). His backstory explains his unusual defensive pose — which is one hand grasping his other wrist in front of him, as if in denial. The Gospel records that Peter protests to Jesus at dinner that he will never betray him. Jesus tells him that he will deny him three times before the break of the next day. This comes to pass. (He also falls asleep while on guard right before Christ is arrested.) The disciple to Peter’s right is James the Minor. He looks into a glass of red wine; you can almost see the reflection of his head there. He was later said to have been stabbed, beaten, clubbed, sawed in two, and thrown off a wall in Rome.

Next is Thomas, who looks up in a gesture of doubt, as if to say to Jesus’ story, “I don’t know about that.” Of course, this is Doubting Thomas, who sees Jesus after his death, still doesn’t believe it’s him, and is told to “thrust [your hand] into my side and be not faithless.” The other two disciples on this side of the table are Philip and Matthew, who in Turkey and Ethiopia, respectively, were said to have been impaled, beheaded, hanged, or crucified. No wonder everyone seems frozen. They’re being given some sort of intuition of what’s to come.

On Jesus’ immediate left (our right) is John. Often called the Beloved of Christ, he bows his head into Jesus’ arm. Some accounts say he was beheaded, others that he died of old age in the year AD 98 in Turkey. Said to be the youngest of the 12 and deemed by Jesus to be his mother’s new son, he looks so sweet I prefer this latter explanation of him as some sole-surviving Ishmael of the crew. Next is Andrew, who holds a knife. He turns to his dining partner Bartholomew, who will be flayed alive in Armenia — as if saying, “This is for you.” Perhaps Andrew’s twisted foot implies his crucifixion on an X-shaped cross. Next is Jude, who is the most emotionally lost at sea. He will later be shot with arrows, clubbed, or crucified. The last two are Simon, crucified in Jerusalem, and James the Major, who will be stoned, clubbed, or crucified there as well. The violent death of Jesus and his disciples are key components of Christianity. I surmise that had Jesus sat under a yew tree, like the Buddha, and simply ascended to heaven, Christianity mightn’t have been what it became. Suffering and death are at the core of its idea of redemption, at least before Martin Luther. And that’s in this painting.

This is a great painting, a masterpiece in pristine condition. But there are no lines to see it, no souvenir industry built around it. Maybe it’s because Castagno died so very young, before the age of 40. He arrived at this height of Middle Renaissance painting when he was barely in his 20s and apparently bound for extraordinary things. But he didn’t live to be part of the revolution. He wasn’t there to develop and advance a style he helped codify. Still, this painting beats with genius, though genius of an era that was dying as soon as it was painted.

*This article appears in the July 6, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!