This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

Here’s what a blurb is: you asking (read begging) a writer with a lofty reputation (loftier than yours, anyway) to bestow upon your book a few spontaneous (that is, semi-coerced) words of ecstasy. It’s you singing your praises in the voice of another, basically. That a person with even a modicum of self-awareness would submit to such a floridly craven, histrionically insecure practice is, to me, shocking. And yet it is the done thing, what editors and publishing houses expect. Long story short, I knuckled under. I agreed to use a blurb on the jacket of my new book, Didion & Babitz.

The rebel spark in my heart, though, wasn’t completely snuffed. If I did get an endorsement, I decided, it would be an endorsement that was also a repudiation, and from a writer both beyond the pale and beyond the grave, Eve Babitz, my book’s co-subject and long dead: “Lili, you did it, you killed Joan Didion. I’m so happy somebody killed her at last and it didn’t have to be me.”

Granted, this quote was a bit of a fake-out since Babitz wasn’t talking about my new book, which I’d only started writing after her memorial in January 2022. But not that much of a fake-out. She was talking about a piece I’d written on Didion for Vanity Fair, in which I’d compared Didion to Andy Warhol, presented her as a figure of morbidity and destruction, calling her “our kiss of death.”

Now, obviously I didn’t kill Didion. Didn’t kill her in a literal sense, didn’t kill her in a figurative sense. Nobody could kill her. She’s too good to kill. But I was flattered that Babitz thought I’d killed her. It made me — me, with my too-ready smile, my wouldn’t-hurt-a-fly ponytail — feel fearsome. Like a literary assassin.

Scribner, to my surprise, was into the idea of a blurb from Eve. Just not that particular blurb. It made the book sound anti-Didion, Scribner argued, when the book went out of its way to give Didion a fair shake; when the book was full of admiration for her. And I backed off because Scribner was right.

Scribner, though, was also wrong. The book was, beneath its judicious and even-handed surface, biased against Didion to an outrageous degree, and the book was, behind its admiring posture toward her, violent toward her. The violence I committed was inadvertent.

But then, I’d committed inadvertent violence before.

In 2021, I released a podcast, Once Upon a Time … at Bennington College, about the writers of the class of 1986 — Bret Easton Ellis, Jonathan Lethem, Donna Tartt. While still a student at Bennington, Tartt had begun The Secret History, a modern classic: the last word in chic whodunits and the definitive campus novel. (The definitive YA novel as well. The Secret History is Harry Potter if Harry fucked and did drugs instead of magic.) The book was a cultural touchstone of my teen years. I’d read it at least a dozen times; memorized huge swaths; had even studied classics in college in the hopes of having an experience approximating that of the main characters.

Ellis and Lethem would talk to me for the podcast. The notoriously reticent Tartt, however, would not. I therefore had to report on her more thoroughly, more rigorously, more relentlessly. It’d never occurred to me that a work as seemingly far-fetched and fantastical as The Secret History could be based in reality. In the course of my research, though, I learned that the book was, apart from the homicidal bits, practically a roman à clef, an imaginative re-creation of her first year at Bennington, when she fell under the spell of a mysterious and possibly sinister professor of ancient Greek and his band of glamorous students.

I found the “real” Julian Morrow, the book’s villain (ancient-Greek professor Claude Fredericks); the “real” Henry Winter, the book’s heartthrob (student Todd O’Neal); the “real” Bunny Corcoran, the book’s murderee (student Matt Jacobsen, who was very much not dead but otherwise as Bunny-like as a person could be, with Bunny’s glasses — “tiny, old-fashioned, with round steel rims” — trousers — “knee-sprung” — and voice — “nasal, garrulous, W.C. Fields with a bad case of Long Island lockjaw”). I even found the “real” Richard Papen, the book’s protagonist: Tartt herself.

Same as Papen, Tartt felt the blight and taint of her origins. (“The Tartts don’t have a real good reputation as far as her father’s side of the family,” said Lovejoy Boteler, a native of Tartt’s hometown, Grenada, Mississippi. “They just had a general reputation as not being liberal in terms of race.”) Same as Papen, Tartt had a father who ran a gas station. (The Southland Service Station on Highway 51.) Same as Papen, Tartt was on financial aid. (Lethem wrote a piece about his time at Bennington, including his friendship with Tartt, who was, he said, “like myself, a financial-aid case there stranded, amid the heirs to various American fortunes.”) And, same as Papen, Tartt took pains to conceal these facts.

I got into Tartt’s secret history, as opposed to Tartt’s official history, the one she trotted out in interviews and in a piece she published in Harper’s just prior to The Secret History’s release. That story “Sleepytown” was about her maternal great-grandfather, a Thomas De Quincey–reading Victorian southern gentleman who dosed her daily with codeine cough syrup so that she spent her childhood in an opium haze. She’d later claim “Sleepytown” was fiction mislabeled as memoir. And fiction it assuredly was, as both her maternal great-grandfathers died before she was born.

I explained how Tartt entered Bennington a product of her time and place: Her senior photo from high school (a “segregation academy” called Kirk) shows a ’70s suburban Scarlett O’Hara. And how, once at Bennington, she became a product of her own imagination: A snapshot taken during her first year at the college shows a starched and ruffled dandy out of post-WWI England. How, in other words, she went from Donna Tartt to “Donna Tartt.” I pulled back the curtain on Tartt — she was as much an autobiographer as a novelist! She was as deliberate a creation as any of her characters! — as Toto pulled back the curtain on the great and powerful Oz: purely by accident, purely out of doggy enthusiasm.

Tartt was less than delighted. There was a spate of fire-breathing letters from her lawyers. (From George Sheanshang, Esq.: “As counsel for Donna Tartt, I want to be certain you understand that … you will be held responsible to the extent that any person speaking or being quoted in your podcast makes any false, misleading or otherwise inaccurate statement with respect to my client.”) Her agents, RCW Literary Agency, even tried to get the podcast yanked from the air on the grounds that it infringed on certain rights — which rights were never specified — and only stood down after an item appeared in “Page Six.” “Acclaimed author Donna Tartt has been sending off some tart legal letters to a podcast … which details Tartt’s time at the school, including an allegedly gender-bending relationship with her male muse.” I’d discovered a cache of letters she’d written Lethem in the winter of 1982–83. They chronicled her romance with yet another ancient-Greek student, Paul McGloin, who referred to her as “my boy” and “my lad.” I also excerpted a classmate’s diary: “Paul is in love with a ‘delightful creature,’ a girl who looks like a little boy … whose sexuality seems to be that she wants to be treated like a homosexual man.”

Tartt’s anger brought me no pleasure, only consternation. I felt the podcast was an act of love, a tribute to the enduring power of her book. Yet she construed it as an act of aggression. And it’s entirely possible that her interpretation is the more accurate. There might have been an unconscious malice — a glee — to my pounce. (Remember Eve’s line, “Lili, you did it, you killed Joan Didion”?) That I didn’t intend to be cruel doesn’t mean I wasn’t. So perhaps the podcast was both: an act of love and an act of aggression. A kiss that was also a kiss-off.

Joan Didion, like Donna Tartt, isn’t just a writer — is a celebrity writer. The two are famous in a way that writers so rarely are. Are famous in a way that actors are famous, or singers. They have a romance, a glamour, a theatricality. They’re known for their books, obviously and of course. But they’re also known for their style, their attitude, their mystique: Didion, with her undersize body, her oversize sunglasses, her Pall Malls and Stingrays and migraines, and Tartt, looking like a female Sebastian Flyte, comporting herself like a southern J.D. Salinger. Which is to say, it isn’t only their prose that fascinates and beguiles, it’s them. Or, rather, their personas.

Coincidentally, I got my first inkling that there might be something of interest behind Didion’s curtain while making the Bennington podcast. Ellis was talking to me about Quintana, Joan’s daughter, also enrolled at Bennington (she’d have been class of ’88 had she not transferred). He became friends with Quintana, and then, shortly after, with Joan and Joan’s husband, the writer John Gregory Dunne.

Ellis, on what it was like spending time with the couple in New York in the late ’80s: “I would walk into their apartment, and Joan would hand me a drink and she would just stand there and not say anything — terrifying, terrifying. Looking back, I often wonder why there were so many young, good-looking guys who were surrounding John, whether it was my boyfriend at the time — Jim — who I think John had a real thing for, or Jon Robin Baitz.” Baitz, then in his 20s, was a playwright. Ellis continued: “My boyfriend Jim was blond, blue-eyed — a lawyer, very straight-acting, very good-looking. So, look, I always assumed John was gay. I never assumed he was not gay. It was just one of those things with that whole crowd: Nick Dunne” — Dunne’s brother, the producer turned writer, who’d come out near the end of his life as “a closeted bisexual celibate” — “Tony Richardson” — the director, who’d died of AIDS in 1991 — “John Dunne. It was a gay man and a wife living the way you were supposed to live. That’s how it was back then. You couldn’t be open. And there were friends of mine who spotted John in certain gay bars late at night, very drunk. Not the chic, hip gay bars, the Times Square gay bars.”

That Dunne may have been inclined toward homosexuality isn’t especially noteworthy. His and Didion’s marriage, one of the most famous in 20th-century literary America, clearly had a great many things going for it, and if erotic chemistry wasn’t among them, so what? (It makes their 20th-century marriage seem 21st-century, frankly — mixed orientation.) So he wasn’t her lover boy. He was pretty much her everything else: her co-writer, her co-parent, her co-dependent. Even her co-her. “People often said that he finished sentences for me,” she once observed, referring to his habit of speaking for her in public. “Well, he did.” And because he did, she had the power of silence.

It was a power she wielded masterfully. When she left Sacramento for New York in the late ’50s to work at Vogue, she was painfully, almost pathologically, shy. A tongue-tied girl from the provinces. “Mouse” was what journalist Noel Parmentel, her first love, maybe her one true love, called her. “She was so small, so quiet — timorous, really,” said Parmentel. Only in the early ’60s did she start to change. After Parmentel talked Ivan Obolensky into taking on her first book, Run River, which had been turned down by a dozen publishers: “‘Buy the thing,’ I told him. ‘It’s breaking her heart.’” And after Parmentel, who would not marry her, told her to marry his sidekick, Dunne, then known as Greg: “The furthest thing from Joan’s mind was marrying Greg, I can tell you that, but I suggested Greg as a possible husband for her.”

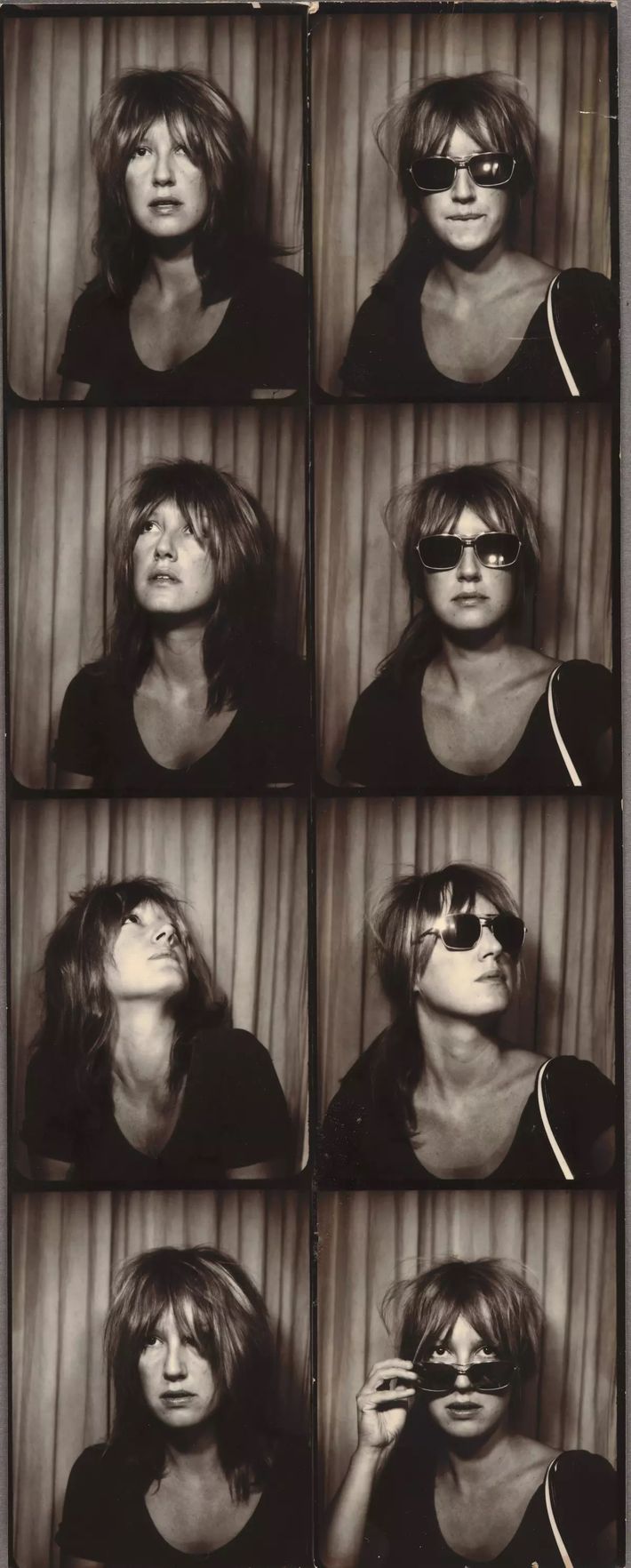

Didion’s motives for marrying Dunne might have been confused, compromised even. Once she was with him, though, she flowered. “She wasn’t the aspirant from Sacramento anymore, the little girl who was too scared to speak,” said writer-friend Dan Wakefield. “Now she didn’t speak on purpose. She understood that not speaking gave her mystery and mystery gave her magnetism. People were fascinated by her. I remember I gave a party. A guy was there — Norman Dorsen — a law professor at NYU, involved in liberal politics and all that shit. Joan was just standing there, not saying a thing. She had on this pair of dark glasses. Norman goes up to her and says, ‘Ms. Didion, why do you wear those sexy, intriguing dark glasses?’ I cracked up and said, ‘I think you’ve answered your own question.’ She was like the sphinx. And when the sphinx spoke, everybody listened.”

Listened even harder when the sphinx didn’t speak. A memory from writer David Thomson: “I saw Joan and John do an event together once. They had this double act going. Someone asked Joan a question, and she waved a hand at John, and he answered for her. It was quite extraordinary, really. He did all the talking, but all the attention was on her.”

And Dunne did more than her talking. Talent wasn’t enough to secure the literary pinnacle. Cunning was every bit as necessary. You needed to vanquish your rivals, shore up your alliances, consolidate your reputation while looking like you were too high-minded for such earthly shenanigans. Dunne, never in contention for the spot of Major American Writer, hustled overtly. (Josh Greenfeld, close to both Didion and Dunne, recalled Dunne’s social-climbing ways: “Buck” — Henry, the actor-screenwriter — “had this picture of John. He’d just broken his arm. It was in a cast. But he was still going to a party.”) Which allowed Didion, very much in contention, to hustle covertly. “John was dominant, and Joan was happy to have him so,” said writer Susanna Moore. “Their relationship was a bit good cop–bad cop. She’d let him execute the cut or the criticism, make the attack. That way she could stay above it all.”

Without Dunne, Didion’s persona — near silent, above the fray, cooler than cool — wouldn’t have been possible. She presented as totally and utterly self-sufficient. (I’m thinking of that famous Julian Wasser photo: her standing in front of a Corvette, the defiant expression on her face, the cigarette smoldering between her fingers.) For her to do that required another person: first her lover-mentor and then the husband that her lover-mentor chose for her.

It’s safe to say that Tartt didn’t like what I did to her in Once Upon a Time … at Bennington College, regarded it as a violation. Would Didion have felt the same about Didion & Babitz? Maybe. Maybe she’d see me as an enemy, someone blurting out her deepest, darkest secrets, secrets that she imagined impugned her very existence. But also, maybe not. Because the thing about Didion: She was always blurting out her own secrets.

She wrote an entire book about Dunne, 2005’s The Year of Magical Thinking, in which she never portrayed him as anything but straightforwardly heterosexual. Yet in a 1977 interview for the Boca Raton News, she said of their relationship, “It wasn’t so much a romance as Other Voices, Other Rooms.” Other Voices, Other Rooms, the first published novel of Truman Capote. A love story, except not between a man and a woman, between a man and a man.

If Didion was hiding, it was in plain sight.

Eve Babitz knew Joan Didion well as a person. (She and Didion were part of the same scene in late-’60s–early-’70s Hollywood, and it was Didion who got her first piece, on the girls of Hollywood High, published in Rolling Stone.) But it was Didion’s persona that obsessed her. And enraged her. This was something I learned only after she died, when I found a letter she wrote to Didion in 1972. The crucial passage from that letter:

Could you write what you write if you weren’t so tiny, Joan? Would you be allowed to if you weren’t physically so unthreatening? Would the balance of power between you and John have collapsed long ago if it weren’t that he regards you a lot of the time as a child so it’s all right that you are famous? And you yourself keep making it more all right because you are always referring to your size.

Babitz felt that frailty was Didion’s drag, a way of hiding how bold she was, how brazen, how cocksure. She ingratiated herself with men, Babitz believed, by betraying women.

Babitz, in stark contrast to Didion, was a writer who was instantly forgotten, obscure before she was known. Only in the past decade — four decades after her first book was published, a decade and a half after her last — has she truly become known.

What happened a decade ago: I wrote a piece on Babitz for Vanity Fair, and it got the ball rolling. Soon after it appeared, New York Review of Books Classics and Counterpoint Press began reissuing her story collections and novels, all out of print. My book on her, Hollywood’s Eve, was released in 2019. Then Kendall Jenner was photographed reading Babitz on a yacht, and she was name-checked — twice — on the Gossip Girl reboot. She was officially launched, the sensation and phenomenon she was always meant to be.

I have a theory. I believe Babitz didn’t catch on in her day, when she was actually living and writing, because she was too much the embodied creature to construct a persona, at least a public one. (Why would she worry about presenting as the thing? She was the thing.) In that Vanity Fair profile, I constructed a persona for her — something else I did by accident — pulling together her wild and chaotic life so that what had been implicit in the pages of her work was explicit: She was her own best character and always had been.

I gathered the details she’d left scattered in various pieces, collected and un-, and in the chapters of books that were fiction posing as non- (“Everything I wrote was memoir or essay or whatever you want to call it. It was one hundred percent nonfiction. I just changed the names. Why? So I wouldn’t get sued!”), shaping it into a coherent narrative, making it all pop: Igor Stravinsky’s goddaughter, Marcel Duchamp’s nude, Jim Morrison’s consort; the mash note she wrote to Joseph Heller when in her teens, the fire she set that nearly burned her alive when in her 50s.

Babitz is now a cultural heroine as well as a literary, same as Didion. What she stands for is pleasure, polymorphous and perpetual; hedonism and mayhem and revelry; recklessness that recognizes no moral boundaries; self-destruction beyond endurance. In short, Babitz is now a brand. And that brand is the un-Didion.

There’s no question that I puff up Babitz in the new book. (Puff her up with good reason. She’s an important writer and a key L.A. mover and shaker, and she’s been overlooked for so long.) At the same time: Do I cut down Didion, in revealing so much about her? Do I take this larger-than-life figure and reduce her, reveal her as puny, unworthy? The answer is an emphatic “no.” As I emphatically do not cut down Donna Tartt in Once Upon a Time … at Bennington College. Didion and Tartt are two of the most successful writers — and, in my opinion, two of the best writers — this country’s ever produced, and I simply show how they did it, how they pulled it off, became who they became.

Late in The Great Gatsby there’s a scene: Gatsby, in a case of mistaken identity, has been shot, a funeral is held. One of the few attendees is Gatsby’s father, a sun-faded sad sack who hands over to Nick Carraway the flyleaf from an old paperback. On it, the daily schedule of young Jimmy Gatz. Self-exhortations include “Study electricity” and “Bath every other day” and “No more smoking or chewing.” Gatsby is the archetypal self-made man, that is, the archetypal American (autogenesis — conceiving, begetting, birthing the self, denying the grip or reality of the past — is, after all, at the heart of the American project, the American Dream), and now we know exactly how he made himself. The schedule is a how-to guide to becoming Jay Gatsby. As a document, it’s as ludicrous as it is touching as it is haunting, and it serves to demystify, to turn Jay Gatsby, the myth, back into Jimmy Gatz, the mortal.

It doesn’t matter that Joan Didion started out as “Mouse” any more than it matters that Donna Tartt started out as a suburban Scarlett O’Hara. Or that Jay Gatsby started out Jimmy Gatz. Even if Nick Carraway is letting you in on the trick behind Gatsby’s transformation, Gatsby is still Great.