What do people want from Jon Bernthal? Ask this question on Twitter, and you’ll get thirsty replies about that smirk, that hair, his flirtatiousness in Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt and his adoration in Wind River, and how he invented the concept of kissing in Sharp Stick. Ask the same of casting directors, and they’ll point to his tough-guy persona, cultivated and refined on The Walking Dead, The Punisher, Fury, Baby Driver, and Widows. But the answer from TV viewers is more difficult to decipher. This was Bernthal’s busiest year in the medium, with two starring roles on We Own This City and American Gigolo and a supporting turn on The Bear that demanded — and received — complexity from the actor. The first two were opportunities for Bernthal to step fully into leading-man status with hour-long episodes and season-long arcs. So, it’s time for another question: Why did they land with such thuds?

It’s been a weird year for TV overall. There was an overabundance of IP, from Disney+’s Marvel Cinematic Universe and Star Wars series to the dueling fantasy prequels of Prime Video’s The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power and HBO’s House of the Dragon. There were series that premiered with very little fanfare but became hits, and others that were canceled too soon. And there was simply too much television to keep track of, as networks experimented with different release models and day-of-the-week drops. Amid all that, it’s not impossible to guess why certain shows got lost in the shuffle. Was demand super-high for American Gigolo, a remake of a Paul Schrader ’80s movie? As police violence against Black people remains disproportionately high, were people excited about watching hours of that in We Own This City? And because Bernthal’s casting in The Bear was kept a secret (not announced during filming, not mentioned in press materials, and not even known by the cast at first), people who stumbled on that show had no prior awareness of his presence. There’s somewhat of a disconnect, then, between the feral feedback pictures and GIFs of this man receive online, and the muted response to most of his work this year — both from general viewers, who didn’t create much buzz around American Gigolo, and awards-voting bodies, who basically ignored We Own This City.

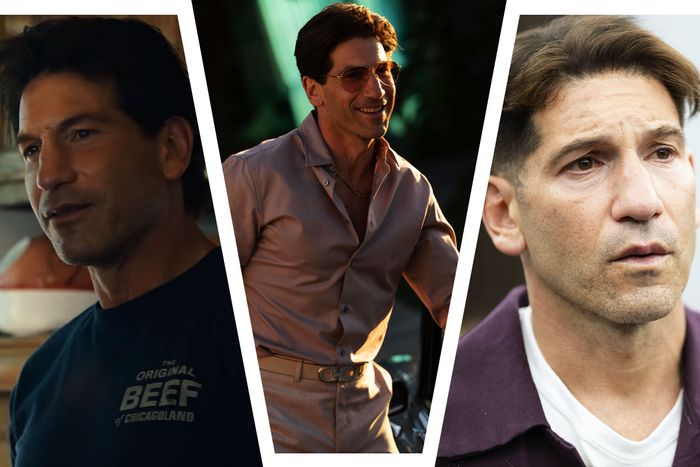

What people missed, though, are three roles that each demanded a specific distillation of the various qualities that make Bernthal so mesmerizing onscreen. He rose to the occasion over and over, with brutish villainy as the main antagonist in We Own This City, bruising vulnerability as the titular American Gigolo, and a combination of braggadocious posturing and warm pride as a struggling sandwich-shop owner who lives on in his family’s memories in The Bear. The quality of these shows was not the same, but within them, Bernthal’s performances were distinctive gradations of the hard-soft balance he does so well, reflecting an awareness of his own appeal and a willingness to dig deeper into his capacity for moral turbulence. Whether or not people were watching, in his most major TV year, Bernthal did the work.

April’s We Own This City premiered a couple months before the 20th anniversary of The Wire, George Pelecanos and David Simon’s previous series about Baltimore and the institutionalized corruption therein. An adaptation of the same-named nonfiction book by former Baltimore Sun reporter Justin Fenton, the HBO miniseries wasn’t an immediately accessible watch. It jumped through time, stopping at various points between 2003 and 2017 as it traced parallel investigations into Baltimore’s Gun Trace Task Force by the FBI and the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice, and bounced around politicians’ offices, police stations, and city corners and neighborhoods to paint a portrait of a city in crisis. It was, of course, bleak, since the Gun Trace Task Force’s crimes were so plentiful. All of that made We Own This City a socially important and entertainingly infuriating watch, but not exactly an enjoyable one — especially if someone were tuning in just for Bernthal-thirst purposes, which were immediately dashed by this man’s awful haircut and unconscionable personality.

Bernthal has been villain before — his breakthrough TV role was murderous stalker Shane on The Walking Dead — but there’s an undercurrent of comedy to the exaggeration of hotheaded Brad in The Wolf of Wall Street, hotheaded Griff in Baby Driver, hotheaded Florek in Widows … you get the idea. These men are capable of absolutely awful things, but Bernthal can summon a level of arrogance so broad and so extreme it almost becomes absurdism. He walks back that approach for Gun Trace Task Force leader Sgt. Wayne Jenkins in We Own This City, though, and in playing the character as more tightly wound and more petulantly defensive, he unearths a simmering core of malevolence. Bernthal’s Jenkins smiles like a scorpion preparing to sting, and that put-upon good-naturedness makes his bursts of violence that much more upsetting: using his baton to smash a man’s liquor bottle while on patrol, then smugly sauntering away; his laugh when he realizes he mistakenly beat a fellow cop at a crime scene, and the swiftness with which he goes from being out for blood to joking about the error; the wiliness with which he insists “I didn’t do it. Wasn’t me,” during FBI questioning about his crimes, and his bratty “I do not feel like telling you that right now” when they ask who is responsible.

Bernthal calibrates Jenkins so that his puffed-up sense of self becomes the miniseries’ through-line. He’s who the other members of the team speak about in scoffing terms to the FBI, like they still can’t believe what he got away with; in the flashbacks, director Reinaldo Marcus Green’s camera tracks Bernthal’s wide-legged physicality and self-satisfied authority during raids, searches, and arrests. Bernthal makes Jenkins a man who believes he was promised more than he got, and whose instability becomes toxic, and the writing is smart enough to make this cop recognizable but not relatable. The dialogue emphasizes all the ways in which Jenkins thought he was better than those around him, and Bernthal channels that conceit in a performance that ends in an echo chamber.

We Own This City served Bernthal well with an odious character who wasn’t just a caricature, but five months later, American Gigolo wasn’t nearly as clearly conceived. The revamp of Schrader’s film, in which capitalism, transactional sexuality, performative masculinity, and feminism combined into a complicated jumble of shifting gender dynamics against an ’80s-consumerist backdrop, lacked all of the filmmaker’s pointedness. American materialism and its debilitating effect on individuality was at the top of Schrader’s mind, but 42 years later, the TV series that took the film’s name didn’t even attempt any broader points about the changing nature of sex work, or the mainstreaming of certain types of fetishization, or the “implicit Puritanism” that has been on the rise culturally in recent decades. Instead, series showrunner Nikki Toscano and developer David Hollander (who was taken off the project after allegations of misconduct, but wrote and directed the first two episodes) made their American Gigolo a jumbled mess by prioritizing the story’s murder element, overloading each episode with the same few minutes of gauzily lit flashbacks, villainizing nearly every female character into a predator or a manipulator, and saddling Bernthal with a character who was thinly motivated and irredeemably flat.

This role should have been what lit Bernthal fans on fire. As Julian Kaye, Bernthal wears an array of well-fitted suits and silky-smooth shirts — before he strips them off. He flirts and teases and gives women that look: the lip-biting, heavily lidded, soft-eyed, enthralled-by-your-existence one he also pulled out in Wind River, Sharp Stick, and Sweet Virginia, and that a character in American Gigolo describes as making “women feel like they’re the eighth fucking wonder of the world.” The aesthetics are all there, until American Gigolo very quickly hits a stylistic and narrative plateau. While ostensibly focusing on Julian after he serves 15 years in prison for a murder he didn’t commit, American Gigolo spends too much time in the past, cycling through the various women who abused Julian: the neighbor who molested him, the mother who sold him to a brothel as a teenager, the madame who pushed him into sex work, the new boss who essentially rapes him on his first night out of the joint. That dynamic pushes Bernthal too often into reactivity, and robs him of the opportunity to claim the character as his own. Where is Julian’s agency or interiority in any of this?

Bernthal tries to find it by deploying bemusement and wariness in his interactions with Detective Joan Sunday (Rosie O’Donnell), who wrongly put him away years ago but is curious about how often his name comes up in the murders and abductions she’s currently investigating. In the early episodes, Bernthal’s presentation of Julian as formal yet tentative in his interactions with others — almost meek — aligns with the series’ initial impression of this character as someone both hardened and cowed by prison. But American Gigolo is so divergent in its timelines and so unsure of where its focus should lie that it denies Bernthal the ability to collapse into the character and trace his transformation. There are suggestions here of how Bernthal can play quiet, wounded, and fragile to greater degrees than he has before, but American Gigolo can’t find a balance for either its story or its lead actor.

That failure from American Gigolo makes what The Bear pulls off even more skillful. The former had a whole season to create the conditions under which Bernthal could make an impression, while all the latter needed was one scene, a couple lines of dialogue the characters experience as memories, and one last close-up. It’s obvious from the beginning of the season that creator Christopher Storer had a clear vision for how the characters we meet at the Original Beef of Chicagoland would be affected by the suicide of restaurant owner Michael. The remaining staff would chafe against new owner Carmy (Jeremy Allen White), Michael’s younger brother, and his professionally trained rules and protocols. Rather than deal with his own feelings of abandonment and isolation, Carmy would pour himself into improving the restaurant and untangling the web of debt Michael left behind. And family and close friends, like sister Sugar (Abby Elliott) and “cousin” Richie (Ebon Moss-Bachrach), would speak of him in such conflicting terms — frustrated and adoring, fondly and peeved — that the audience’s own conception of Michael would grow fuller and more encompassing, despite not meeting him until sixth episode “Ceres.”

When “Ceres” opens with Mikey holding court in the Berzattos’ family kitchen, telling a story about a wild night out that Richie hangs onto, Sugar rolls her eyes at, and Carmy indulgently smiles at while putting together the braciole that Mikey is supposed to be cooking, it makes perfect sense that Bernthal is the revealed actor. By this point, Michael has become a bit of an enigma: someone who kept hardship close to his chest, who pushed away others who got too close, who wanted the best for Carmy but couldn’t voice it, who was an increasingly distracted boss and an uneven businessman but still, through magnetism and open-heartedness, inspired loyalty and love. These are all qualities that align with Bernthal as a performer, and director Joanna Calo follows Michael around the kitchen as he aggressively salts meat and commands the room in a way he clearly always did. His voice is engaged and engaging, drawing his listeners into the story while remaining in control of it. He’s at ease in the kitchen environment that transcended both his personal and professional lives. He’s the elder brother and the best friend, and all the burden and inspiration of those roles is communicated in just a few minutes.

The Bear shows Michael again only one more time, but the impact Bernthal makes in that scene (shot in one day in Los Angeles at the end of the season’s production schedule, to accommodate Bernthal’s American Gigolo commitments) endures through season finale “Braciole,” which is named after Michael’s customary dish and includes his last words to Carmy in the form of a short letter Richie hands over after holding onto it for months. In “Ceres,” Bernthal approached Mikey like of course he would expect everyone to look toward him for entertainment, and his grasp of the character was so strong you can practically hear his voice in “Braciole” while Carmy reads the note: “I love you, dude. Let it rip.” The note is direct in a way Mikey’s storytelling wasn’t, provides the affirmation Carmy wanted for so long, and also offers up the season’s fairy-tale ending via the recipe for family-meal spaghetti. After a season defined by Michael’s absence and the problems he left behind, “Braciole” ends with a short-term solution for the restaurant’s woes and a visual homage to the man whose myriad contradictions came to such vibrant life in Bernthal’s hands.

So where does Bernthal’s TV career go from here? We Own This City was a miniseries, while American Gigolo hasn’t yet been renewed for a second season, but its first season could stand alone in a self-contained, if ultimately unsatisfying, way. The Bear is rumored to start filming again in February, but who knows whether Bernthal’s Michael will be back; in fact, there’s an argument to be made that the character served his purpose and doesn’t need to return. The only upcoming project on Bernthal’s IMDb schedule is Snow Ponies, an action-comedy film The Hollywood Reporter describes as following “a crew of seven hardened men who travel across a vicious landscape to deliver a mysterious package.” That certainly sounds Bernthal-ian, but it also suggests it might be a while until the actor graces our small screens again. The final shot of The Bear’s first season reminded us of the affective power of Bernthal’s uninterrupted attention. This year, he deserved more of ours.