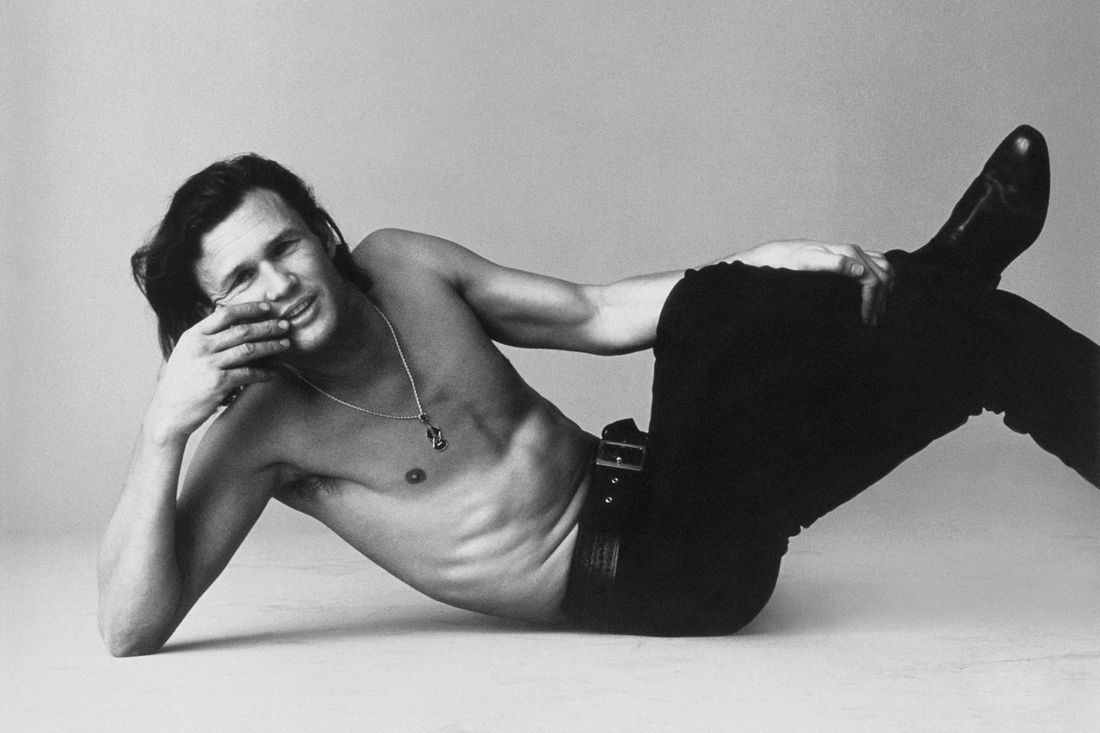

In Taxi Driver, a campaign worker named Betsy (Cybill Shepherd) goes on a lunch date with disturbed Vietnam vet turned cabbie Travis Bickle (Robert De Niro). She says he reminds her of the character in “The Pilgrim, Chapter 33,” a soulful, self-lacerating Kris Kristofferson song off his 1971 album The Silver Tongued Devil and I. “He’s a prophet and a pusher, partly truth and partly fiction — a walking contradiction!,” she says. “I’m not a pusher,” intones Travis, whose ability to interpret metaphor is only slightly greater than that of a dog. But he still buys the record, and as the clerk hands it to Travis, Scorsese makes sure to show us the cover image: Kristofferson, pictured from hips up, thumbs hooked into the waistband of his jeans. That’s how cool Kris Kristofferson was by the mid-’70s: Not even the Rolling Stones got their own commercial in a Martin Scorsese movie.

Kristofferson, who died on Sunday at 88 at his home in Maui, once said The Silver Tongued Devil and I captured the “echoes of the going-ups and the coming-downs, walking pneumonia and run-of-the-mill madness, colored with guilt, pride, and a vague sense of despair.” The singer and actor wrote a lot of tunes and made a lot of movies that captured those sensations, from heavily covered songs “Sunday Morning Comin’ Down,” “Help Me Make It Through the Night,” and “Lovin’ Her Was Easier (Than Anything I’ll Ever Do Again)” to Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, and the 1976 version of A Star Is Born.

If you take in the totality of his decades of work as a musician and an actor, it’s astonishing in its breadth and quality. Of all the stars who existed simultaneously on vinyl and celluloid, he had the most elegantly balanced career — an artist who brought the same level of craft and integrity to each world. He never gave the impression that he thought of acting mainly as a way to promote his musical career, or the reverse. Nor did one overshadow the other, as was the case with David Bowie, Bing Crosby, and Frank Sinatra, great musicians who could be good in the right role but were never thought of as equally committed to both crafts.

Kristofferson was. His work was so closely intertwined in creation and reception that it was obvious how they fed each other. The characters in his songs and the ones he played in movies were all very much Kristofferson characters: refracted, grimed-up shards of himself, with plausible deniability and elements of exaggeration or critique. These were men who had dirt on their hands and booze on their breath. They got beaten or killed or made mistakes that marked them as pariahs forever.

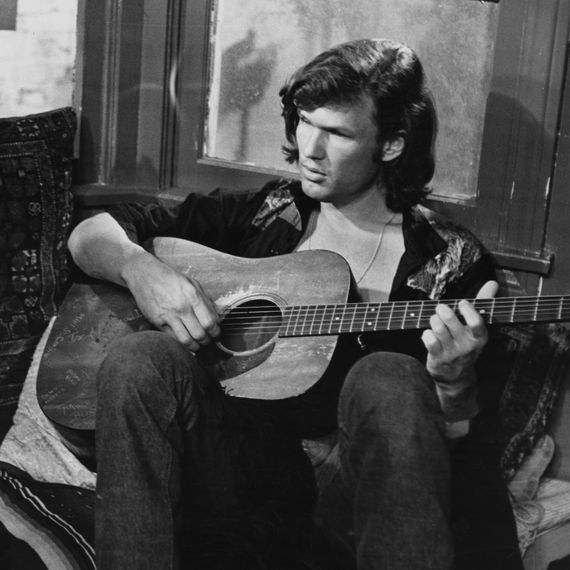

Born in Brownsville, Texas, to a military family, Kristofferson earned early bona fides as a real-life sensitive tough guy. He held blue-collar jobs in high school, played football, and was a good enough rugby player to get written about in Sports Illustrated. But he wasn’t a stereotypical jock. He loved words — maybe more than anything else, except women, who, according to multiple biographers, practically flung themselves at him from the instant puberty hit. (He was married three times, to Fran Beer, singer Rita Coolidge, and onetime law student Lisa Meyers.) Kristofferson was also a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford, where he boxed, continued playing rugby, and got a showbiz manager who he hoped would make him into a successful singer-songwriter, which he saw as a fast path to his dream job, becoming a literary novelist.

Kristofferson’s parents hated the Hemingway-wannabe road their son was on and pushed him to enlist in the Army. Though he completed Ranger School and became a helicopter pilot, he eventually quit to continue chasing his dream. His parents disowned him in a letter written by his mother: “Nobody over the age of 14 listens to that kind of music, and if they did, they wouldn’t be somebody we would want to know.”

Over the next decade-plus, Kristofferson kept his head down and continued to be Kris Kristofferson, the rugged poet with the narrow eyes, the world-weary charisma, and the frog-inside-a-cello voice. He moved to Nashville with Beer and struggled to pay for treatment for their son’s esophageal problems. He got a job as a janitor at Columbia Records and bent rules against approaching the talent in order to get his songs in front of performers he loved. One was Johnny Cash, who ignored him until Kristofferson got drunk and landed a helicopter on his lawn. When Cash stormed out of his house to find the longhaired dude who mopped up at the studio sitting in the cockpit of the chopper, Kristofferson supposedly presented Cash with charts for what would become one of his signature singles, “Sunday Morning Comin’ Down.” (Kristofferson later told Cash’s son it was actually “a different song that wasn’t any good.”)

Cash not only went on to record multiple Kristofferson tracks but advised him on his craft. Yet even Cash’s magic touch couldn’t transform him into a star. Throughout the ’60s, Kristofferson remained known within the industry as a pipeline for fresh material and not much more. His first notable songwriting credit was “Viet Nam Blues,” covered by Dave Dudley in 1966; it was just big enough of a success to get him signed to Epic Records, where he recorded a single (“Golden Idol”) that made no particular impression. His subsequent songs were recorded by the likes of Roy Drusky (“Jody and the Kid”), Ray Stevens (“Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down”) Jerry Lee Lewis (“Once More with Feeling”), and Waylon Jennings ("The Taker”). But he couldn’t get any traction as a performer.

Then stardom finally happened, all at once — and sort of by accident. In all his years of struggle, Kristofferson never gave much thought to acting. It wasn’t where his interest lay. His first film performance was in Dennis Hopper’s Brechtian anti-western The Last Movie; he did it as a lark because Hopper was his friend and had just made his directorial debut with one of the biggest hits of the ’60s, Easy Rider. The Last Movie was two years away from being released when casting director Fred Roos saw Kristofferson perform at the Troubadour and impulsively asked him to audition for the lead in one of his projects, Monte Hellman’s existential highway parable Two-Lane Blacktop. Kristofferson said yes to the tryout even though he wasn’t actually interested, showed up drunk to the audition, and left before reading any lines.

Despite tanking a great opportunity, there was buzz around Kristofferson as an up-and-comer, someone who had the counterculture imprimatur that was increasingly required for movie stardom in the ’70s. Plus, Columbia Pictures heard Roos liked him enough to offer him a lead role in a movie, so they sent him writer-director Bill Norton’s screenplay for Cisco Pike. Kristofferson said yes, despite not having any formal acting training. Although he didn’t care for the film, the role became his Hollywood debut, and featured a soundtrack powered by Kristofferson originals that would show up a year later on The Silver Tongued Devil and I. By the time the movie finally hit theaters in 1972, Kristofferson’s ex-lover Janis Joplin had died and had a posthumous smash with “Me and Bobby McGee.”

Kristofferson was such a hot commodity by then that he started working with major directors, including Lewis John Carlino (The Sailor Who Fell from Grace With the Sea), Martin Scorsese (Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore), Paul Mazursky (Blume in Love), and Sam Peckinpah (Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia, Convoy). The keystone in the domino chain to stardom was the Barbra Streisand version of A Star Is Born, in 1976. It became the second-highest-grossing movie released that year, exceeded only by the original Rocky. From that moment on, Kris Kristofferson was always with us. There would never be a point when you would go through a year listening to music or watching movies or TV without running across him and thinking that he was good, actually; the kind of good that sneaks up on you.

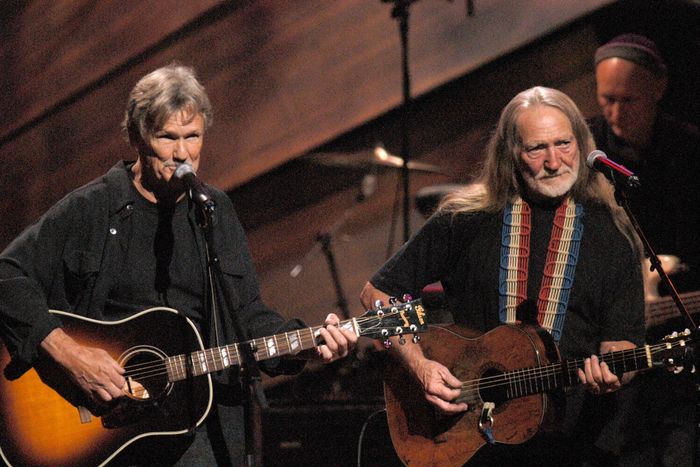

Onstage and on records, Kristofferson was a solid draw on his own or as part of a multi-act bill, and a great collaborator for anyone with even a hint of a country sound. Arguably his biggest era of commercial success as a musician started in the ’80s as part of the Highwaymen, a quartet rounded out by Cash, Waylon Jennings, and Willie Nelson, all pioneers in the so-called “outlaw country” subgenre. He also used the stage as a soapbox or pulpit for progressive causes, including Native American and civil rights and the dignity of Palestineans, environmentalism and feminism, and opposition to U.S. involvement in Vietnam, the Gulf War, Latin America, and Iraq.

As an actor, he moved through the ’70s and ’80s as an offbeat leading man with a wood-carved face — somebody whose name (like Adam Driver’s today) didn’t mean much in terms of box office but signified both art and populism in a way that mysteriously helped get movies funded. Even when a film he was in didn’t announce itself as Art (like A Star Is Born or the Blade movies), it had artful aspects, and he could be good — occasionally great — in it.

The role of self-destructive alcoholic rock star John Norman Howard A Star Is Born was originally supposed to be played by Elvis Presley, but Presley’s manager, Tom Parker, demanded top billing and 50 percent of the soundtrack. Kristofferson hated the movie as well as the experience of making it (he called it “the worst thing I’ve been through since Ranger School”), but it was ironically appropriate that Kristofferson replaced Elvis. Throughout his life, Presley always fantasized about being a hip and critically acclaimed film actor like Marlon Brando, whom he idolized. In the ’70s, Kristofferson kinda looked like a young Brando and was a double-threat music-and-movie star like Elvis. But from the very beginning of his stint in Hollywood, Kristofferson insisted on a baseline of hard truth that marked him as a serious actor even though he’d slipped into movies through a side door and never taken an acting class in his life. He held the same standards for music. His choices in both represented who he was and always wanted to be: a creative force who had ideas and ambitions and rarely did anything just for money. That’s why you never caught him in the equivalent of a bubblegum Elvis timekiller like Blue Hawaii or Change of Habit. Even in Kristofferson movies that ended up bombing with audiences and reviewers — like Heaven’s Gate, which public opinion belatedly turned around on, and the financial thriller Rollover, which remains justifiably forgotten — you could at least detect a few of the qualities that might’ve piqued his interest, back when it was just words on paper. Right around the time that Elvis left the building, Kristofferson walked onstage and took the spot Elvis had always dreamed of: the music-star matinee idol who was taken seriously on the big screen, not because he’d finally proved he was an artist, but because there was never any question that he was one.