Finally, Leonardo DiCaprio Can Relax

As you watch Leonardo DiCaprio in The Revenant haul his twisted body over miles and miles of frozen tundra, his face a mask of rage and pain, his snuffles and grunts resounding through the theater, you might find yourself thinking, Give him his fucking Oscar already. Who cares if his performance as the 19th-century explorer Hugh Glass isn’t his most inventive, that it’s more a testament to his will and endurance than his artistry? Academy voters apparently believe that it’s Leo’s time, and it surely is. With any luck, now that he’s finally won that award — and he can stop having to tell interviewers that it doesn’t matter how often he has been nominated and gone home empty-handed because the Oscars really aren’t “on his radar” and, besides, the most important thing in the world is fighting climate change — he’ll stop laboring to prove what a GREAT ACTOR he is and take a breath onscreen, and I don’t mean a breath that comes at you hard from 12 speakers. He’ll remember what he knew, instinctively, when he began performing.

You have to go back to DiCaprio’s early work to recall the joy he radiated in front of the camera. It was in 1993 that he appeared in his first starring role as the teenage protagonist of This Boy’s Life, a fine adaptation of Tobias Wolff’s memoir partly undone by Robert De Niro’s face-pulling as Wolff’s abusive stepfather. DiCaprio plays a fatherless boy who strives to project manly defiance, who smokes and swears and defaces property and slouches like Elvis but can’t help turning into a gleeful, laughing child with his mom (a tender Ellen Barkin). The emotional seesaw DiCaprio homes in on in Tobias became the basis for many of his best characters: shrewd, discerning child-men who grow more and more cocky — and then reckless — and then are suddenly wide open, vulnerable. In many instances, they end up dead.

DiCaprio’s performance as the developmentally disabled Arnie, brother of Johnny Depp’s Gilbert, in What’s Eating Gilbert Grape (first nomination, first loss) is revealing in a different way. For starters, it’s his most radical transformation. He thrusts out his upper teeth, scrunches up his features, and desynchronizes his limbs, squealing and leaping about with floppy exuberance. But it’s not just his physical contortions that win you over. The fatherless Arnie is an incorrigible attention addict, and DiCaprio (whose parents divorced when he was a 1-year-old and who mostly lived with his mom) lets the scene-stealer in himself rip. One of the most famous stories about him is that he was thrown off the kiddie show Romper Room at age 5 for being disruptive and trying to hog the spotlight, and even now, in “mature” roles (and despite a life spent evading paparazzi), there’s a glint in his eyes when his characters are noticed and applauded.

It was the ham-handed, overdirected Western melodrama The Quick and the Dead (a vehicle for Sharon Stone but with a stellar cast that includes Gene Hackman and a youngish Russell Crowe) that showed something else about DiCaprio: Following a (latish) growth spurt, he had become beautiful. You look at him and gasp: Every feature works. As “the Kid,” who longs to prove to his dad (Hackman) that he’s a spectacular gunfighter, DiCaprio gives the movie a lift. He twirls his guns and bows to the crowd, grooving on the acclaim — and setting himself up for a fall. Underneath the goofy exhibitionism — through the goofy exhibitionism — he gives you glimmers of the Kid’s tragedy, the longing for respect that pushes him beyond his natural abilities. DiCaprio proves that he can give a bouncy, funny performance that still cuts deep.

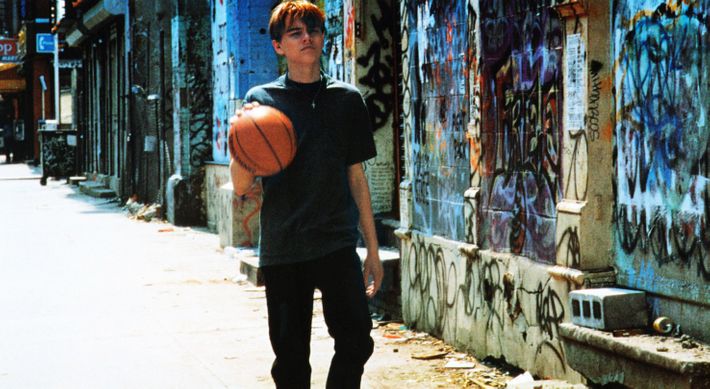

In the film of Jim Carroll’s The Basketball Diaries, DiCaprio goes even deeper. Once more he plays a fatherless teen, a delinquent, and (like Tobias Wolff) a budding poet. But he’s also a junkie. The movie builds to a scene in which he collapses against a door and begs and weeps and threatens his mother (Lorraine Bracco), hitting notes of anguish that he’d never hit before (and, truth to tell, hasn’t hit since). The young DiCaprio often measured himself against River Phoenix, who’d just died. Here was the kind of performance that Phoenix didn’t live to give.

Critics, meanwhile, made the obvious comparisons to James Dean, but DiCaprio shows no relish for the psychological self-plumbing that made Dean’s Method stylings so riveting — and, when it got weird, so discomfiting. DiCaprio just couldn’t purge the showman in himself. At the end of The Basketball Diaries, we see that the movie’s voice-over narration was part of the character’s one-man stage show, and DiCaprio breaks into a mischievous little grin when the applause erupts. James Dean would have been too immersed for bows and grins.

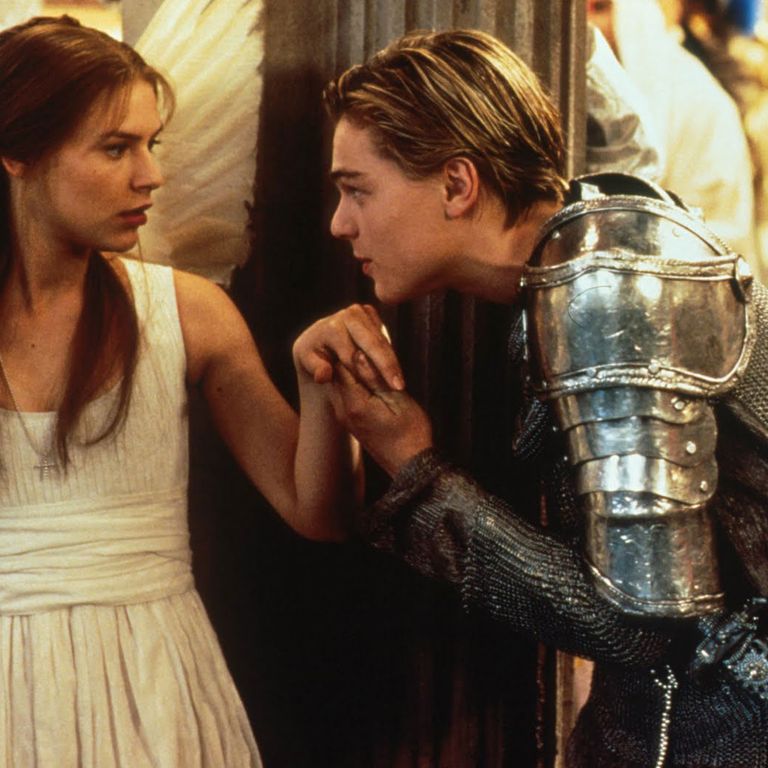

There were signs, though, that DiCaprio couldn’t do everythingwell. He should buy up existing copies of Total Eclipse, in which he makes a game but risible attempt to play the poet Rimbaud as depicted by tony playwright Christopher Hampton. When Rimbaud moans to his lover, Verlaine (an unusually dire David Thewlis), that “the only unbearable thing is that nothing is unbearable,” DiCaprio seems so callowly American that you almost wish he’d gone the camp route and used a Pepé Le Pew accent. But then, DiCaprio is never camp. He’s as earnest onscreen as Bruce Willis is smug. Only a little better was Baz Luhrmann’s whooshy Romeo + Juliet. Yes, it was a hit, and, yes, it made DiCaprio a teen dream. But he’s not up to what little verse that Luhrmann leaves unmolested. His beautyis all he has going for him.

His next starring role was, of course, the Big One: James Cameron’s cornball epic, Titanic. In early scenes, his Jack — the name his character Tobias told everyone to call him in This Boy’s Life because he thought it sounded manly — is jaunty and spring-heeled, with a dash of cunning, a daredevil and an artist. What made those teenage girls go back and back and back to theaters, preferring the first half to the later spectacle, is what happens between DiCaprio and his co-star, Kate Winslet. Physically and temperamentally different, they find an exquisite balance: He lightens her heavier, more brooding, more actressy style, while she magnetizes him, bends his rhythms to her emotions. You feel them discovering each other, even when their dialogue is laugh-out-loud terrible. Most of the supporting players are high on the hog (Billy Zane’s curling eyebrows evoke Snidely Whiplash), but it’s hard to laugh at lovers who are so sublimely in tune.

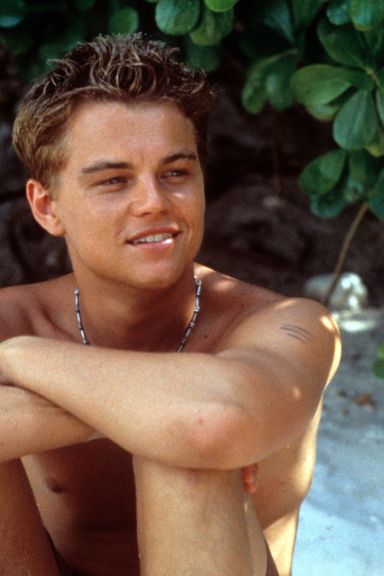

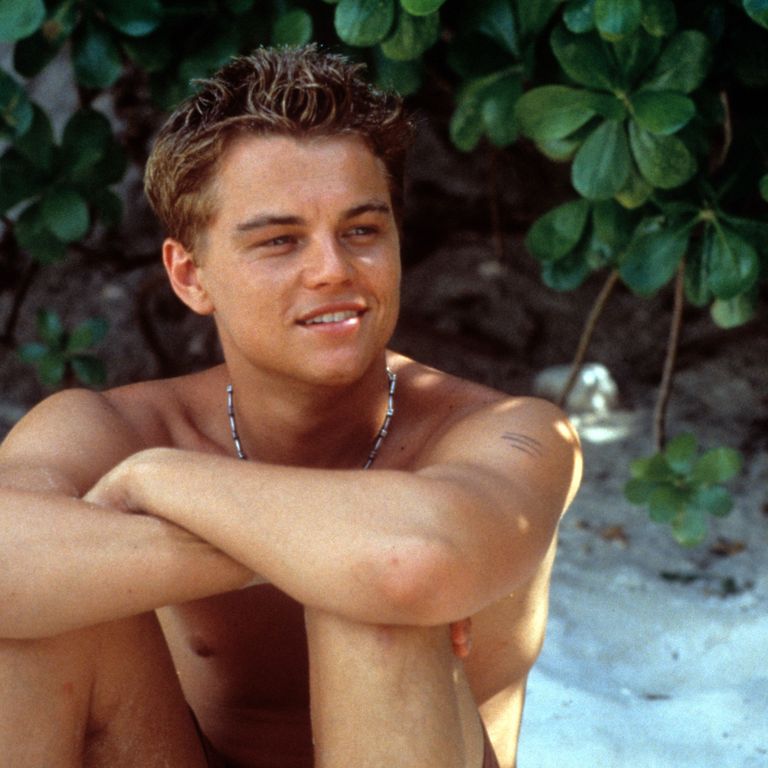

Did Titanic halt young Leo’s rise as an actor? It’s possible. Exhausted by the shoot, he did a quickie swashbuckler of no consequence, The Man in the Iron Mask, and had a startlingly effective supporting role in Woody Allen’s dour Celebrity as version of his old co-star, the hotel-room-destroying Johnny Depp. But then came the Oscar-nomination snub, which must have left him — whatever his public demurral — with an angry sense of entitlement. It wasn’t long before he was famous for his entourage, his “Pussy Posse,” and his evident need to date 20-something supermodels as if to make up for high-school rejections. He became a prince. By the time he made the pretentious The Beach, two years later, some of his lightness was gone. His few good moments were rooted in that familiar DiCaprio persona: the inexperienced young man who pretends to be something he isn’t — here, the kind of hero he identifies with in romantic movies and video games — and then finds himself in the presence of real horror, real death.

Things were about to get even heavier. Enter Martin Scorsese, whom Harvey Weinstein reportedly promised an Oscar (Scorsese had been denied the statuette more times than DiCaprio and had at least three masterpieces under his belt) for Gangs of New York. But the movie, for all its ostentatious pleasures, was a mess, and DiCaprio got the worst of it, dwarfed by a titanically scenery-chewing Daniel Day-Lewis and floundering in a poorly conceived romance with Cameron Diaz.

It’s worth posing an indelicate question: Is DiCaprio a lightweight — or maybe a borderline middleweight? That’s not meant as a slur. A lightweight can be every bit as thrilling to watch as a heavyweight, and some of the great screen icons belong in that category. Cary Grant was a brilliant lightweight, though he proved capable of hitting shockingly dark notes in Hitchcock’s Notorious. Bogart was a light-middleweight who could suggest great depths and, as Dobbs in The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, go believably loco. But the real heavyweights — Day-Lewis, Olivier, Brando, Vanessa Redgrave, Dustin and Philip Seymour Hoffman, etc. — have the histrionic resources to be both huge and finely calibrated. They were trained, both formally and by working in the theater. You can snicker all you want at actors who refer to their bodies as their “instruments,” but there is much to be said for the boot-camp of acting classes (Method, Meisner, clown, improv, etc.), dance, and voice work. Obviously, the best film actors modulate what they do for the screen. They understand that they can’t project to the camera — they have to let the camera read them. But that technical foundation gives them size.

DiCaprio doesn’t have that foundation. His training was in commercials, TV sitcoms, and soaps. He has a voice without much timbre, and his accent work is spotty. When he was younger, he could move with confidence, but nowadays, when he has to suggest stature, he can’t quite fill the space. And with some exceptions, the kinds of roles he has gravitated toward don’t use his natural rhythms. They’re Oscar bait.

In J. Edgar, under heavy makeup and with a director (Clint Eastwood) who didn’t know how to protect him, he’s often laughable — although he eventually wins you over with his guts and honesty, his refusal to caricature any aspect of J. Edgar Hoover’s struggle. He gets by in Christopher Nolan’s Inception by looking forlorn in multiple timelines (his wife has issues) while the CGI swirls around him, but there’s nothing distinctive about his work. Quentin Tarantino wrote him a juicy theatrical turn in Django Unchained as a to-the-plantation-born slave owner, a glibly homicidal little prince, and it’s fun to see DiCaprio as a villain. But not quite as much fun as it’s meant to be. He does a lot of sloppy gesticulating and shouting, and he doesn’t rise above the movie’s cartoon level. Then, once more a victim of Baz Luhrmann’s whoosh, he was the Pretty Good Gatsby. If you’re rooting for DiCaprio — as I am, always — you can correct for his artificiality by rationalizing, “This is a poor boy named Gatz pretending to be a mature aristocrat named Gatsby, so his habit of saying ‘old sport’ is meant to sound phony.” But when DiCaprio is frozen and on a pedestal, his sorrow doesn’t read. His face looks heavy and slack, and there doesn’t seem to be much going on behind that big brow. It’s as if he has attached anvils to his soul.

There have also, admittedly, been triumphs and near triumphs since Titanic. Steven Spielberg used DiCaprio’s gifts — and, I think, brilliantly exploited his limitations — in Catch Me If You Can, where the tempo is lickety-split, but not just for the sake of razzle-dazzling you. Spielberg takes his style from the flimflam-artist protagonist, Frank Abagnale Jr., another of DiCaprio’s naughty boys trying like mad to impress a mostly absent father. He’s not just in tune with the motion of the film, but that motion is the key to the grim subtext: Frank must go fast to keep from going deep. If he deserved an Oscar for anything post-Titanic, it was for this performance. But Academy voters don’t tend to recognize breeziness, which they equate with superficiality. You must suffer for a golden statuette, and DiCaprio was ready.

The best of his Scorsese collaborations is in The Aviator, where his Howard Hughes shares Frank Abagnale’s headlong approach to life. His Hughes is a boy heir who fights to prove to the world that he can dominate the space, that he can challenge the laws of speed and gravity — and good sense. That cockiness gives him immense charm and glamour, but it also leaves him dangerously exposed. What undoes him, though, is not his enemies. He’s undone by his own mind, by an obsessive-compulsive disorder that arrests his motion and renders him impotent.

DiCaprio is just as good in Blood Diamond as another cock-of-the-walk, a wiry con artist who’s most fully alive when he’s backed into corners. His briskness keeps the film — a nightmarish melodrama centering on brutal African diamond mines — from getting bogged down by its message.

More unusual is his reunion with Winslet in Sam Mendes’s adaptation of Richard Yates’s Revolutionary Road, in which DiCaprio does pull off some weighty, Oscar-bait psychodrama. Note, though, that he’s not playing against type. His suburban philanderer could have been Titanic’s Jack once, but what was buoyant and self-assured is now plainly dodgy. In the climactic scene, DiCaprio loses his supreme balance: Winslet has forced him into the moment, which leaves him flayed. A superb performance — but the movie got bad reviews and no nomination for DiCaprio. Maybe it hurt too much to see our dream couple hit a different kind of iceberg — their marriage.

DiCaprio’s steadiest collaborator in the last decade has been Scorsese, who’s plainly enthralled with his leading man — and his leading man’s ability to get financing. But it’s worth asking whether — in The Departed, Shutter Island, The Wolf of Wall Street, and even The Aviator — the director’s amphetamine tempos sometimes force DiCaprio to indicate rather than “be.” There are moments when he seems to have a metronome ticking in his head.

He has enough goodwill in Hollywood that he would probably have won the Oscar for The Wolf of Wall Street if the film hadn’t been so controversial. I thought his performance was one note, although he admittedly hit that note harder and harder and harder, finally lurching around in a drug-addled purgatory. The world’s heart went out to him when that year’s winner, Matthew McConaughey, stopped on his way to the stage to console DiCaprio, who managed a wan smile and said it was okay. It’s possible he won his Oscar for that one moment. All he needed was to give a performance — preferably one in which he could suffer floridly.

Well, he did, plainly putting himself through hell, which he has done before and maybe has decided that he needs to do. Anyone who can simulate being chewed by a bear (even a CGI bear) deserves at the very least a merit badge. The Revenant has been a monster hit, and a lot of people have been wowed — and put through the wringer — by it. But I found director Alejandro González Iñárritu’s mix of show-off, macho technique and bogus Native American spirituality repugnant, and its ending — the hero nobly forswears revenge but promptly gets it anyway — a cheat. And I think DiCaprio’s Oscar-winning performance is his least interesting, although the other nominees are relatively weak and I’m not going to cry that an injustice has been done.

DiCaprio is now feeling, on some level, fulfilled, no matter how much he might publicly discount what that win actually means. Very few actors rise above the Oscar. If nothing else, they know that the first paragraph of their obituaries — maybe even the first line — will include the compound adjective “Academy Award–winning,” and they can rest for a time.

DiCaprio is a complicated case in so many ways and full of contradictions. He’s a party animal who works diligently to ensure the future of life on Earth. He only takes projects that challenge him, that involve creative risk, but he seems tighter, more hidden as an actor than he was at the beginning of his ascent. It’s as if the two sides of him — the intellectual and the instinctive — have grown distant from each other. Maybe with this Oscar, DiCaprio will feel free to do what he hasn’t in years, which is not to overthink his performances and be strangled by some mistaken idea of seriousness. Think what he could do in a movie by, say, David O. Russell, who’s not the easiest guy to work with but who’d give him room to be playful, to loosen up and think on his feet. DiCaprio doesn’t need to drag himself over frozen tundra anymore. He can wear his seriousness lightly.