What do more years on Earth add up to? Wisdom, maybe, or at least lessons in what went right or, occasionally, very wrong. At New York Magazine, we’ve spent time recently reflecting on the value of age and what comes of it. We reached out to famous artists and thinkers in their late ’70s and older and asked them to reflect on the lessons they’ve learned — and, in some cases, are still working to master — over the course of their long lives. Scientists, activists, and a few Star Trek captains told us what they wish they’d known when they were younger, what they value now, the accomplishments they are most proud of, and the wrong turns they took.

Contents: Activist Dolores Huerta | Conductor Zubin Mehta | Scientist David Baltimore | Actor George Takei | Poet Susan Howe | Actress Rita Moreno | Actor Patrick Stewart | Actor William Shatner | Theater Director Woodie King, Jr. | Socialite Martha Bartlett | Actor George Bartenieff | Civil Rights Leader James Lawson | Architect B. V. Doshi | Dancer Yvonne Rainer | Dancer Gus Solomons Jr. | Poet Ishmael Reed | Actress Chita Rivera | Saxophonist Sonny Rollins

‘The Local Priest Told Everybody They Should Pray to God for a Wage Increase Instead’

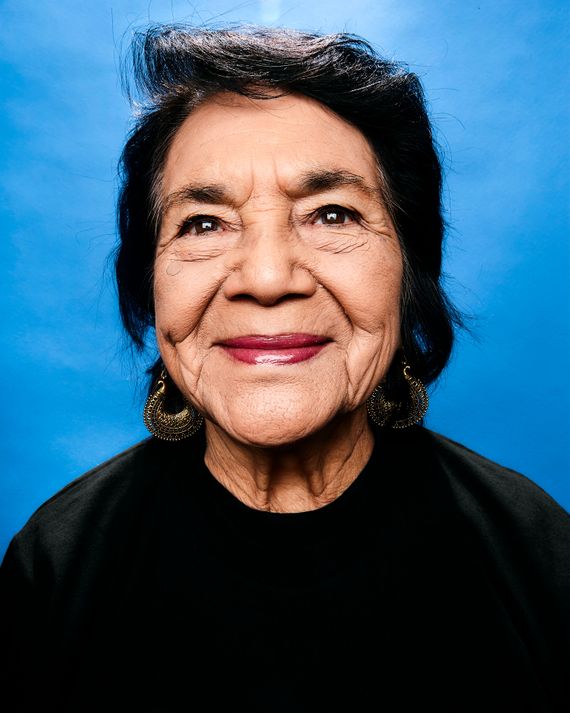

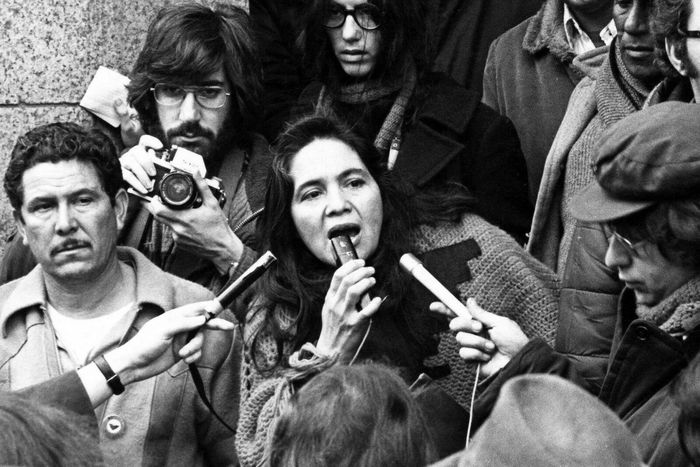

Activist Dolores Huerta, 90

Anyone can be an organizer, but a lot of people are inhibited by doubt that they can convince other people. If they can break that barrier of fear, they can be organizers. My teacher in organizing was an old-school gentleman named Fred Ross Sr. This was in Stockton, California. He taught me that if people understand why they’re in the situation that they’re in, and how they can change the situation, then they have the power to change things. He changed my entire life. I quit teaching.

When we first started organizing in one small town south of Bakersfield [in 2005], we were going to have a march for a wage increase in farmworkers. Our organization was pro-gay, pro-choice. The local priest told everybody not to go to our march, that they should pray to God for a wage increase instead. We had our march — and after, the women in the community went and convinced their priest that he should support us in spite of our differences. After that, he actually had a Mass for my birthday. So people can change.

We started the national grape boycott with house meetings, getting people to invite us to their homes. It was making them understand that they’re the ones who had to do it; nobody was going to do it for them. We started the boycott in New York City, and we had farmworkers go out and ask people to form a picket line in front of a store selling grapes, to pass leaflets out to people. In Grand Central station, we passed out 25,000 leaflets every single day. This was one of the big areas where Cesar Chavez and I had a difference of opinion. The company we were up against, it grew oranges, potatoes, and grapes. He wanted to boycott potatoes, and we had this big argument. I said, “When people think of potatoes, they think of Idaho, not California.” When the grapes were being sold at the New York auctions for 75 cents a box instead of $20, that’s what convinced them to come to the table.

Chavez and I both believed in nonviolence in grassroots organizing, but we differed a lot in strategy. I think it’s the difference in the way women and men think. Women, we avoid conflict, and in doing that, we don’t really fight for our position. One of the things I regret is that sometimes I didn’t fight hard enough against a tactic I thought was wrong and was very costly to the organization. During the Imperial Valley lettuce strike in 1979, we had a moment where I think we could have negotiated and settled the strike, and we didn’t. It resulted in a death of a worker, who was killed by the employers. I think we could have settled that strike, but women have a lot of intuition that we don’t listen to. Also, a lot of us women worry about our looks. Of course, that’s really important when you’re younger. But right now, every time I put makeup on for a Zoom call, I think, We, as women, are getting so ripped off by the cosmetics companies.

Back in the day, there were very few grassroots organizations, and now a lot of young people are motivated. You see the Black Lives Matter movement, the Me Too movement, ending gun violence — you see how quickly people can be mobilized on the internet. Even the women’s marches, how quickly people can be brought together. We’re going to be going into the elections in November registering people to vote virtually. The message can be spread so quickly, and that’s exciting. I learned about Ahmaud Arbery’s death, and the solidarity jog, how many people took part. That was all virtual.

One negative thing about the online issue, though: You realize that you don’t know your neighbors. Yesterday, on my daily walk, a woman greeted me and said, “Are you Dolores Huerta?,” and turns out she’s a schoolteacher. And a man shouted out, “Are you Dolores Huerta?,” and it turns out he just bought a house, and he recognized me because he was active in a labor union in L.A. I guess we’ve had social distancing in a different kind of way about relating to our neighbors. And that’s different than when I was young. When I was young, you knew everybody on the block.

—As told to Amelia Schonbek

‘In the Beginning, I Wasn’t Very Flexible. I Had to Learn That.’

Conductor Zubin Mehta, 84

I did one year of university in Bombay — the plan was for me to go on to medical studies — but then I went straight to Vienna to study music when I was 18. I was so immersed in music that I didn’t miss the education I would have gotten. I do now, but I don’t spend sleepless nights thinking about it.

My father was a great musician, and he gave me lots of advice. So did Hans Swarowski, my conducting teacher in Vienna. It was because I followed their advice that I had my first important jobs at 25 as music director of the Montreal Symphony Orchestra and assistant conductor of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. But I also got advice from others that I didn’t follow as a young man but do now, especially in opera. When I first started conducting opera, I had to learn on the job, and when you do that, there are pitfalls. Wagner’s Ring cycle is one of the hardest works to learn — it’s 17 hours of music! — and when I first did it in Florence, the orchestra wasn’t as good as it is today, and the singers weren’t very good either, so of course I had big problems. I did the best I could, but in the beginning, I wasn’t very flexible. I had to learn that.

I’m not studying new things too much, but when I restudy the classic works, I’m always discovering new details. It’s like when you look at a painting of Botticelli’s: At first you notice all the beautiful women, and it’s only later that you pay attention to all the birds and plants at their feet. In music, that kind of happens continuously.

—As told to Justin Davidson

‘We Still Go Back and Read Darwin’

Scientist David Baltimore, 82

It’s like a bad dream come true. I started off as a virologist, have read a lot about the influenza epidemic of 1918–19, and I’ve always felt a wonderment that it doesn’t happen more frequently. There are so many viruses out there in the world.

Between my junior and senior years of high school, I did a visit at a mouse-research laboratory in Bar Harbor, Maine. It was on a whim, a suggestion of my mother’s. What I discovered over that summer was that the forefronts of research were available to me. I could work on a problem that no one else knew the answer to. It was a simple problem, not earthshaking in any way, but it was mine. There was a moment when I knew something that no one else in the world knew, and I could communicate that with my fellow scientists, and it was a piece of a larger scientific puzzle. I then decided that’s how I wanted to spend my life.

Even though I won a Nobel Prize [at 37], and I pretty well knew I wasn’t going to make another discovery as dramatic as the one that won me the prize, I continued on, and we’ve made some pretty dramatic advances in my laboratory over the 50 years since that discovery. I had gone into science because I wanted to try to understand the behavior of living things. And every little step is an excitement to me. Even if the advance in knowledge that’s made is small, and there are only 27 people who care about it, I still get a thrill from it. I’ve never lost that.

It’s been a period of 60 years since I first was exposed to scientific questions. When I first began work as a scientist with viruses, the virus itself was the unit of interest and we couldn’t get any smaller than that. Over time, we had the ability to pull out the genetic information, at higher and higher resolution, and finally at the highest possible resolution. We can now do that at will. All of that gives us a much richer understanding of the complexity of life, and the ability to alter life, in very subtle but ultimately meaningful ways. All of that is new. But at the same time, it’s the same questions. We still go back and read Darwin.

The time between the appearance of new viruses is long, relative to the political calendar. So we don’t have the political will to maintain our worry about new viruses over decades. And yet that is what we have to do. Once a virus is loose, the time for it to spread is very short, much too short for us to ramp up new capabilities. We have to prepare ourselves for it. We’ve done very poorly in that regard.

—As told to Amelia Schonbek

‘I Enjoy Being a Participant’

Actor George Takei, 83

After the war, we lived on Skid Row, and my father opened up an employment office in Little Tokyo to find jobs for people coming back from these barbed-wire-prison camps; then he found a dry-cleaning shop in the Mexican-American community of East L.A., and he bought it for a song and sold it for a profit; then he found a grocery store in South Central and built that up and sold it. I don’t know how he did it, but then in 1950, he went into real estate, and he was successful at that because he built good relationships with the Japanese-American community. I mean, they struggled, and I saw how hard they worked. So now — I don’t play golf! Being an actor means being between engagements is a fact of our chosen profession, so I’ve liked being engaged. I speak about my internment experience; I raise awareness. I enjoy being a participant — I served for 11 years as Mayor Tom Bradley’s appointee to the Southern California Rapid Transit District Board. So the next time you’re in Los Angeles, you’ll come see our subway that we managed to build.

—As told to Helen Shaw

‘I Don’t Think I’ll Live to See How We Climb Out of This’

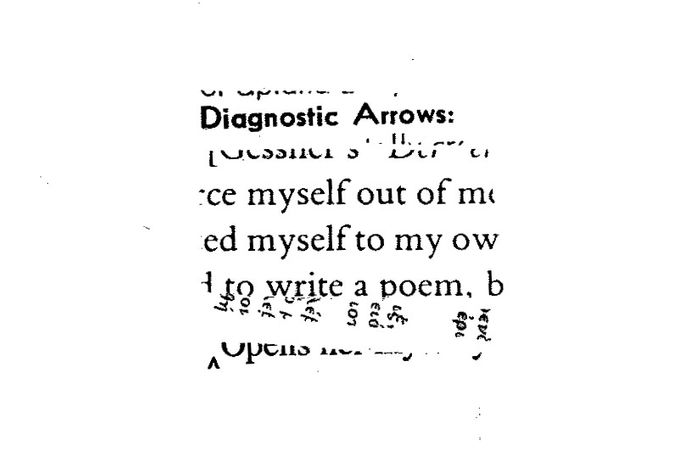

Poet Susan Howe, 82

One of my primal memories is the day of Pearl Harbor. I was 4 years old, and my father had taken me to the Buffalo Zoo, and the polar bears were acting insane. A crowd had formed around them, and they were jumping up and down and blowing water on each other and galloping around. I remember my father, who just loved animals, saying, “They must know something tremendous in the world has happened somewhere.” And that night on the radio, we heard about Pearl Harbor and then he went away to war.

Since this COVID-19 has hit, I’ve wondered about everything. About life, death, and America. I think it’s the most overwhelmingly shocking event, both metaphysically and politically, that I could have imagined. Because it’s so mysterious. One doesn’t know what to do; one doesn’t know how long it’s going to last or how it will strike. There were terrible things — like Vietnam, obviously. Iraq. I understand that there’s something misguided and terrible in our foreign policy. Yet something held. Good things happened. With the Kennedy assassination and then MLK’s assassination, things started to get very ugly and very complicated. This thing is terrifying in a different way that I can’t put my finger on.

Also the fact that I’m old and I know I’m at the end. I don’t think I’ll live to see how we climb out of this. I’m sure we will, somehow, but I think it will take longer than my life. And I won’t see it. I’ve never felt that before.

When I see words trashed and stepped on by Trump, it’s very, very, painful. I remember so well during the war how we listened to Roosevelt on the radio, how he seemed so eloquent and so wise. In the course of my lifetime, I’m thinking — then we had Roosevelt, and now we have Trump. But not only that. In my lifetime, polar bears have become endangered and now almost extinct. That strikes me as connected.

I think of how lucky I am. I’m in my house right near Long Island Sound, and I take a walk every afternoon. Usually, I was this old woman walking alone — a nut out there — but now there are people, and you speak to them, and they smile, which is a new experience. And I’m so struck by birdsong. They all seem to be talking to each other in wonderful languages I don’t understand. They seem to be signaling that there’s another world in the sky.

Yeats’s and Stevens’s last poems both concerned birds. That seems interesting to me, how they go to the birds’ cries, a cry that is beyond language. The last poem in Stevens’s collection is called “Not Ideas About the Thing But the Thing Itself.” It’s about hearing a bird’s cry “at the earliest ending of winter, in March.” It struck me how that is so literally true about the pandemic. In March, we had ideas of the thing but not the thing itself. The thing itself came, slap, later, at the earliest ending of winter.

My mother lived into her early 90s. but most of the old women that I knew were kind of bedridden and sort of had given up by the 80s. Being an energetic, active woman in one’s 80s is much more common now. I’m capable of driving and working and taking care of myself. I love doing t’ai chi, meditation, yoga, things like that. But what’s sad about this moment is that it isn’t the same doing it on Zoom. The human body, a group of you, even if you do not touch, there’s something profound there about what you do with your hands that you don’t get on a screen.

I don’t know if I’ll write another book. I think the book I just did is probably my last. I don’t have the stamina. My sense of career ambition is absolutely gone. I think there was a shift, after the very sudden death of my husband, that was just as inexplicable as this pandemic. He went to bed fine one night and was dead in the morning. An embolism. Trying to find my place, what the hell to do next after that — that produced a book and a kind of, I think, profoundly new way of writing. The sudden horrible mystery of death, of finding a dead person, it caused a big change in my work and a change in me. I’m more concerned with explaining — I don’t know what. Trying to understand. Trying to understand.

I do love to think about certain poets who wrote great work until the ends of their lives. That’s rare, but Whitman certainly did, and John Ashbery did. But some of these poets, it becomes like a kind of prayer, and a belief in the word.

Whitman’s late poem “A Clear Midnight” is so beautiful. The final line is “Night, sleep, death and the stars.” I think about that line as a woman lying down and going to bed at night at 82. How could you get anything more holy?

—As told to Amelia Schonbek

‘I’m Not Afraid to Apologize’

Actress Rita Moreno, 88

I’m in a business where egos are very, very fragile. And I have learned how to handle people who have problems in the kindest way I can. And sometimes being kind simply means being very honest and direct. And I am known — if I’m not known for anything — I am known for being very plainspoken. And people may get angry, they may get hurt, but ultimately they really respect you for that. I’m also not afraid to apologize. That’s a very hard thing for people to learn, especially people who are sensitive and emotional. I’m both of those things, still. I have learned how to say I was wrong with grace. I’m very sorry. I know I hurt you. And I won’t do that again. It’s hard to do.

—As told to Jackson McHenry

‘I Had No Idea That My Father Was Ill’

Actor Patrick Stewart, 79

I wish that I had known when I was a child what I only learned about five years ago. That was that in 1940, when my father came back from France when the Expeditionary Force was being overrun by the Nazis, when my father got back to the U.K., he had severe PTSD. Of course, it wasn’t called that then; it was called shellshock. It was the kind of thing where he displayed some of the symptoms that we now know can come about as a result of trauma.

There is so much help now for you. I am myself a patron of an organization called Combat Stress, which deals with veterans who have PTSD. My father was a man of violent changing moods, particularly with alcohol. And my home life, from the age of 6 to 12, was unpleasant and scary. I learned about PTSD, and it made me so sad to realize, because I have publicly over the years given my father a very bad press because of the violence toward my mother. When I was saying that, I had no idea that my father was ill. Please understand. I’m not saying that what you did is okay. Now, violence is a choice that person makes. It is inexcusable. But if I had known that he was ill, then in some way it might have affected my relationship with him and even, indeed, might have helped him to deal with it. But I didn’t know.

—As told to Jackson McHenry

‘Everybody Else Doesn’t Know Anything Either’

Actor William Shatner, 89

What I’ve slowly discovered is that I know nothing, and really, the longer I live, the more I realize I know nothing. And what is dawning on me very slowly is that everybody else doesn’t know anything either.

You know, I was around when Jonas Salk came up with the vaccine for polio. Again, I’m in Montreal, and I’m hearing about people being lamed, hearing that the American president walks with canes. I see Tiny Tim crossing the television set. I saw this handicapped child walking across the television screen, and I felt sorry — but then when I had my own child who was healthy and watched this child … oh, it was terrible. But with Salk, here was the way to prevent the most dreaded scourge. The sense of relief that went through mankind! That’s what will happen here. Being a competitive person, I would like to think that American labs will be the first to come up with it, but it doesn’t matter. The word is that the 30 or 40 labs that are working on it now will all get it, and so nobody will make a fortune on the 7 billion doses they need to make to inoculate everybody to allow us to meet.

—As told to Helen Shaw

‘You Cannot Make It Alone’

Theater Director Woodie King, Jr., 82

I think one of the worst things that could happen to a young artist and young people is that they’re not members of any organization. Before I left Detroit, I went to an acting school called Bloomfield Hills, and every summer they would bring in just these unbelievably brilliant artists, like Basil Rathbone from London, and they would talk to us. There were maybe one or two African-Americans. But I would take pages and pages of notes, so when I came to New York, I could look up, say, Harold Clurman, and he would remember me. You cannot make it alone. You cannot. You must be a member of Theater Communications Group and the National Theatre Conference. You must be a part of the current Establishment. I wouldn’t say the world is going to come to an end if they’re not members — but it would certainly be a lot a lot easier if they are.

—As told to Helen Shaw

‘Whoever’s Been President Has Usually Been a Friend’

Socialite Martha Bartlett, 94

My grandfather, when I was 4 years of age, he asked me what I planned to do with my life. I thought, This is a very strange question. He was paramount: You always had to have a direction. And whatever you are, you have to be the best. I honestly and truly think that in a funny kind of way, if you do things that you’re good at, it brings a lot of happiness into your life.

If you had four children, which I had, and had to entertain a great deal (maybe 50, 60 every month for dinner), you just had to manage, period. It didn’t matter if you wanted to. That’s one of the disciplines.

All my life, I brought people together that have become great friends. It’s one of the most satisfactory things you can do. I have a friend, and she doesn’t share any of her friends, and I don’t understand that. I like to share everything. You do it with a light touch so you don’t take it too seriously.

Whoever’s been president has usually been a friend. Oh, it’s much ado about nothing, so what — it’s all part of history. But I always appreciated to be part of it. The Cuban Missile Crisis was just one of many episodes. You can imagine, I was in on all of them. You just feel very grateful, and it was very exciting. But there was not much I could do about it. And I’m going to tell you something: Don’t dwell on a lot of things you can’t do much about. Stick in life to the things you can manage. You’re not part of the missile crisis, so just leave it alone.

My mother worried all the time, about everything, and she went past 100. But I think it’s a waste of time. The Spanish flu was far worse than this. The Second World War was horrendous. Am I going to sit here and worry about this virus? I hope I have better things to worry about. I have a garden that I love and 40 years of catalogues from Sotheby’s and Christie’s that have taken five or six weeks to sort through.

—As told to Amelia Schonbek

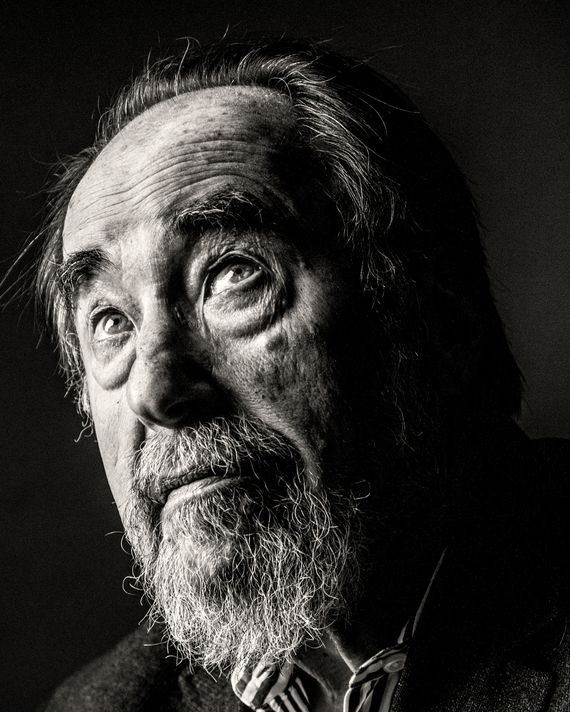

‘The Theater’s Only Alive When There’s a Background of Tumult and Passion’

Actor George Bartenieff, 87

I don’t have advice to myself; I have advice for others! I’m very concerned with any way that I can pass on my experiences because these days there isn’t that community of theater that we had. Back then, there were a lot of non-actors in theater, and that was wonderful. When I was living on 10th Street, I had to walk one block to a storefront where they were doing early Happenings — and again, that was a door opening to an experience that was filled with ambiguity and mystery.

But I think we became too rich, and that led to excesses of all kinds. Think of that time: The feminist movement and the civil-rights movement (which was a kind of a pinnacle) and Woodstock — all these things were a height of rebellion against the bomb, against the Doomsday Clock. Even so-called amateurs had something to say, so they began to perform. Never mind the pandemic, the theater has abdicated its responsibilities — it’s no longer interested in being relevant; it’s more interested in entertainment. The theater’s only alive when there’s a background of social tumult and passion.

—As told to Helen Shaw

‘You Are on a Life’s Journey’

Civil Rights Leader James Lawson, 91

I knew I wanted to be a pastor since before I was in high school. And not just a preacher-teacher. A pastor, a prophet. I knew pretty consistently that my life’s work was going to be rooted in serving people in and through a congregation. Biblical faith is mostly a record of some 1,500 years of people grappling with the life force of the Earth and what it means to their lives in their own times. And a major feature of those God-human encounters that are recorded in the Scriptures is that you are on a life’s journey, and you hit major obstacles including pandemics, but also how you can be unafraid, cultivate your heart and soul and mind and strength, cultivate your neighbor, and you can persevere and endure. Martin Luther King — and I can name a whole slew of others — were black pastors, all of whom saw that to be a pastor, you had to challenge racism and segregation. To be a pastor meant that you had to deal with the issues of economic enslavement. Black people could not be a teller at a bank. Black people could not teach, could not be a fireman or a policeman. The prohibitions against black people was the nature of slavery and post–Civil War life in America. Any pastor who’s not concerned for how his or her people make a living, are able to support their children and their families and their environment, for the total wellbeing of their parishioners, is not a pastor. That’s one of the things people don’t see that came out of the ’60s — you’ve got a model of religion that’s very different from the Pat Robertsons, the people Trump has pulled into his orbit from the churches. It’s not a model of hating people, rejecting people. It’s a model of trying to build compassion through justice and truth. That’s what I do say in my teaching and in my work in the community. Concentrate on discovering the power of nonviolent love and truth. And organize, organize, organize, out of the philosophy and strategic history of nonviolence. There is no alternative. Use the power of nonviolence in themselves to organize against the wrong, to realign our history.

—As told to Amelia Schonbek

‘There Is Always the Sunrise’

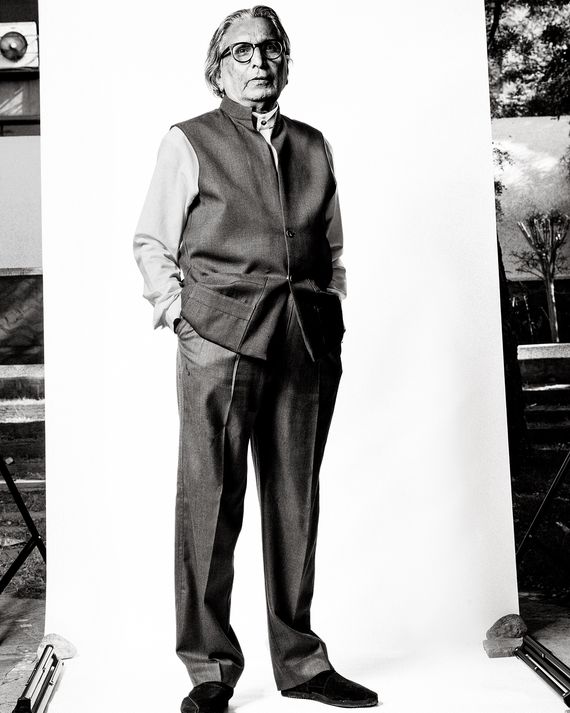

Architect B. V. Doshi, 92

My grandfather had lost one of his eyes when he was working on carpentry, but he always told me, “At least I have one eye.” Optimism! I learned that there is always something you still have that you can work with. And that has helped me a lot. Every time there is a problem, there is also an alternative. One should never lose hope.

In my extended family, I see four generations. What I have learned from them is that you will never know what is going to happen, but there is always something that is going to be exciting. COVID is a great example of uncertainty, and yet the world is going to continue and go on. Beyond your expectations, beyond your fears, there is always the sunrise. I’ve learned about eternity in another way, as a cyclic order, and that has given me a chance to think about architecture in a different way: Is it possible to create something that may be only a germ and over time will germinate into a forest?

—As told to Justin Davidson

‘It’s Gotten Harder to Make Work’

Dancer Yvonne Rainer, 85

When I first started dancing, my mother was able to give me a little money, and I took three classes a day in the late ’50s, early ’60s. My first dance teacher was named Edith Stephen. She had a studio on the fifth floor in the Village, and a friend of mine, a musician, was taking classes there. The first class just took. I had no idea of my physical limitations — it was a physical rush to find out This is for me. From there, I went to [Martha] Graham, to Merce [Cunningham], and I took a lot of ballet classes, though I never had any turnout. I became a choreographer because I knew there would be no company that would accept me with my particular limitations — a long torso and short legs.

I had begun to make my own solos in Robert Dunn’s class in 1960–61 — he was a devotee of John Cage. That first piece I made is still performed: It was Three Satie Spoons. Then I began to get grants; I got my first Guggenheim in the late ’60s and a MacArthur later on. It’s not easy being a choreographer unless you institutionalize yourself in some way with a big company. It’s gotten harder to make work because my dancers are all teaching and choreographing themselves. It’s hard to get six mature people together; by the time they’re in their 50s, they have their own commitments. But I’ve kept going. In fact, I was supposed to do this duet with my co-worker in a gallery somewhere. Of course, it was closed down. It’s the first time I’ve had a dead stop in my enterprises.

Spacing wise, this six feet of distance creates a whole new public choreography. You’re conscious of your body in space in a formal way, keeping away from people and the absence of touching with friends you ordinarily hug. There’s a whole different kind of physicality that you assume with this invisible adversary.

—As told to Helen Shaw

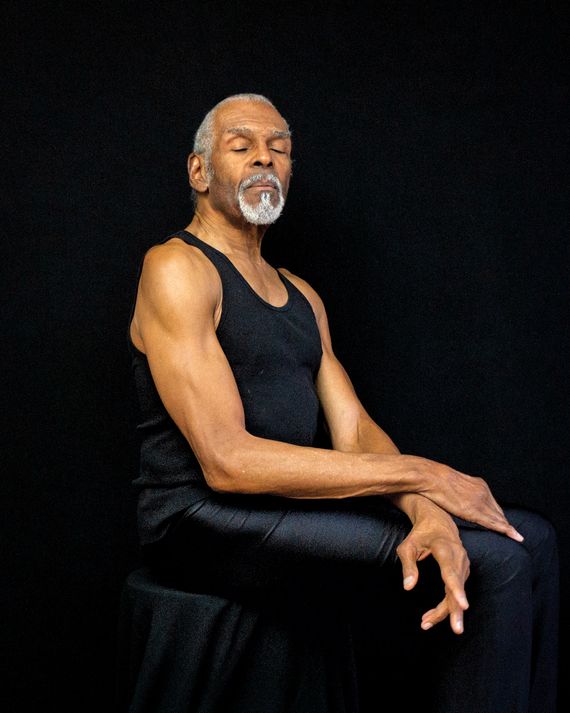

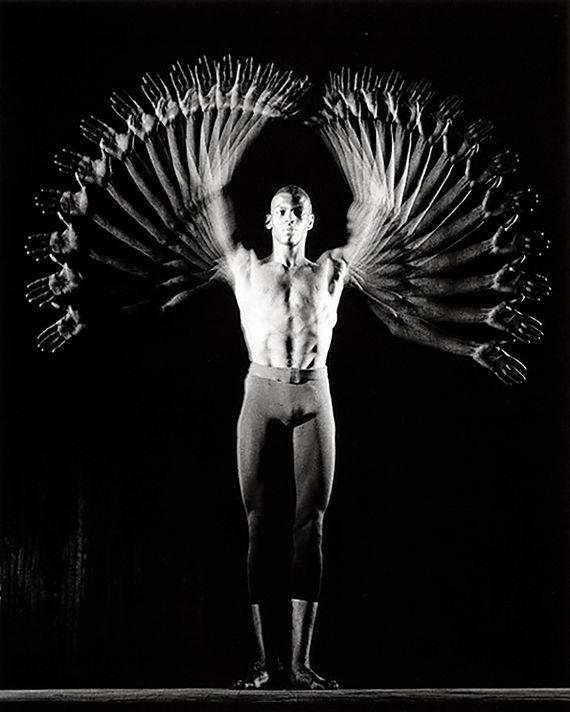

‘I Am Going to Sue Merce Cunningham’

Dancer Gus Solomons Jr., 80

There’s some advice I wish I hadn’t followed. Merce Cunningham said, “Wear weights on your ankles; it will strengthen your back,” and so I forced myself to dance and do class that way. And that was damaging my back progressively. I am going to sue Merce Cunningham. But you know, he grew up when I grew up. No one knew what to do. I had very good teachers, but the state of somatic knowledge was inchoate at that point. No one knew how to train the muscles, how to compensate for different proportions and anomalies as they do now. I had scoliosis that developed over the years from the mid-’80s until 1997, when it started to impinge on the nerves in my left leg. So I hobbled around not knowing if I was putting my left leg down — I just couldn’t feel it. In 2012, when the curvature had progressed to 58 degrees, the doctor said, “We need to do surgery.” They managed to reduce the curvature to 24 degrees. There’s still damage in the left side, and it’s rods, it’s rigid, so I have very little movement in my spine. The middle of my spine is one piece that limits my bending forward and my twisting, so I have to work with that. I do work with that. Then I broke my hip in 2018. I’m still recovering. I was going to get a revision with the doctor who replaced my left knee, but then I discovered I had prostate cancer — so all surgical revisions were off the table.

I’ve had radiation. That’s going okay, though I don’t know. The urologist said, “It’s aggressive,” which I’ve just learned is the substitute term for stage four, which sounds fatal. But he never said stage four, and it hadn’t spread, so I had radiation and hormone therapy. I’m strong; I’m exercising every day. My stability is not what it needs to be, but I’m working on ways to compensate for that. I’ve reconciled myself to using a cane and seeing what possibilities there are. I’m accepting the changing instrument as it changes — not regretting what I can’t do but seeing what I can do and using that.

—As told to Helen Shaw

‘I’ve Seen Tokens Come and Go’

Poet and Novelist Ishmael Reed, 82

The kind of life I was living in New York, with all its temptations. That was something I really look back upon as being a lot of time wasted. Because I’d come to New York broke from a working-class background with no prospects. And then six years later, I’m in French restaurants and dining at Doubleday townhouse and my name is mentioned in gossip columns and the Daily News and the New York Times. It occurred to me that they were grooming me to be the next token. At 82, I’ve seen tokens come and go. They get a lot of publicity and recognition, and the problem with tokenism is that the New York literary Establishment, which has been serving tokens for 100 years, is that when they are no longer useful, they get dropped and somebody takes their place. There was Ralph Ellison, who saw younger writers as his competition. I interviewed him; I said, “Why are you so hard on younger writers?” Turns out he hadn’t read many of them. But he wants to be the token. Then there was the other alternative. Langston Hughes, who cultivated and mentored younger writers. So I follow Langston Hughes’s example in more ways than one. I live in a black neighborhood. He lived in Harlem. He supported younger writers. I support younger writers. If you Google my name and look up news, some of the younger writers acknowledge that.

—As told to Jackson McHenry

‘I Know I’ve Had Some Pretty Good Taste’

Actress Chita Rivera, 87

Your life is like one big family; you have to treat it as such. There’s no small people, only small minds. I’m a very positive person, even though I don’t sound like it today. I love the group of amazing friends that I have accumulated through my whole life, which actually represent me. My oldest friend is a girlfriend that I’ve got, Dee Dee Wood. We went to ballet school together. She and her husband at the time choreographed Mary Poppins, The Sound of Music — she’s a very gifted person. It’s as if not a day has gone by with our lives.

I’m doing a series with Seth Rudetsky, and it’s called Chita Rivera and Friends, and I’ve just been having my friends on every Saturday. I had Rob Marshall and Scott Ellis and Jason Alexander, and we reminisced about The Rink. I think God has a way of reminding us that we did something okay when we have friends like this and we can go over the memories that we’ve had. These are people that I’ve known for a very long time, and they’ve become successful, and they’re great, and they’re friends of mine. It makes me feel great about myself. I know I’ve had some pretty good taste.

—As told to Jackson McHenry

‘I Accept the Theory of Reincarnation’

Saxophonist Sonny Rollins, 89

I have been more or less quarantined for a couple of years. I have a pulmonary fibrosis, I have a walker, and I don’t really go out much. I just go out when my friend takes me to the doctor or the bank. So having to stay in the house is not an entirely new situation for me. Actually, I’m quite happy as far as that is concerned. With the virus, well, I’ve got a lot of feelings about that.

What is working for me? I’ll tell you. I accept the theory of reincarnation. I’ve been a person that’s been interested in the so-called afterlife for most of my life. When this virus came, it was still somewhat of a shock. A plague. We all know there have been plagues all through history, so it’s nothing new for mankind, but this is the first one of this magnitude that we have had. What does it mean?

If you accept reincarnation, then you know that we’re not meant to be living on Earth forever. I don’t ascribe to that feeling that life is here for us to enjoy. That it’s just about me having a good time and not owing anybody anything. If that’s all that life means to you, then yeah, I guess a plague is a big deal. What’s more important to me is living by the Golden Rule. Now, recently, there was an article that got some attention. It was revisiting the fact that all of the ancient disciplines and religions that we know of in our world, every one of them — Christianity, Islam, Judaism, Taoism, Buddhism, Confucianism, Zoroastrianism — all of these disciplines preach the Golden Rule. Do unto others as you would have done unto you. I’m not the best person in the world, and I’m not the worst, but there’s a reason for my being here.

When you get to be my age, your friends drop off one by one. I just lost another old friend of mine who passed away. I have to accept that. He was 93. When I look back on my life and what I could have done, how much better I could have been, what a wiser person I could have been — there are little things that I look back on, but I don’t want to look back. What’s important is what I’m learning now and how am I dealing with what I have to do now.

I also feel, in this fantastic universe that we’re in, it’s all good! There’s a reason for everything that happens. If you’re a great performer and all of a sudden you can’t play anymore, there’s a reason for that. I really went up the wall when I realized I couldn’t play anymore because of my condition, around 2014. There was definitely a grieving process. I got great joy in practicing. I used to go by the ocean in California, back in the day when it was okay to do things like that, and play by the ocean. Or after I played at a nightclub, we’d get off at three, four in the morning and I’d drive up on the Palisades Parkway and go into a secluded spot and play. I loved just playing my horn. So it was very hard. I went through a period of despair. Finally, it came to me: Sonny, you have to be grateful that you had a life in music, instead of decrying the fact that you can’t play.

I was very fortunate as a youngster. I was born in Harlem, and all these great jazz musicians were all around, these people I heard when I was 2 and 3 years old. I got my first saxophone when I was about 8 years old. I realized early on that I loved music, that this is what it was all about. I was born on the right track, so to speak. This is probably having to do with my karma, my previous births. I came into this world loving music and having an opportunity to play it — that’s some good karma that I accumulated someplace in my previous lives. I don’t know when. I don’t want to know. Whatever it was, I’m here in this life now and I have to go on and get better and better. As the Buddhists say, you get more into the light.

—As told to Amelia Schonbek

*A version of this article appears in the May 25, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!