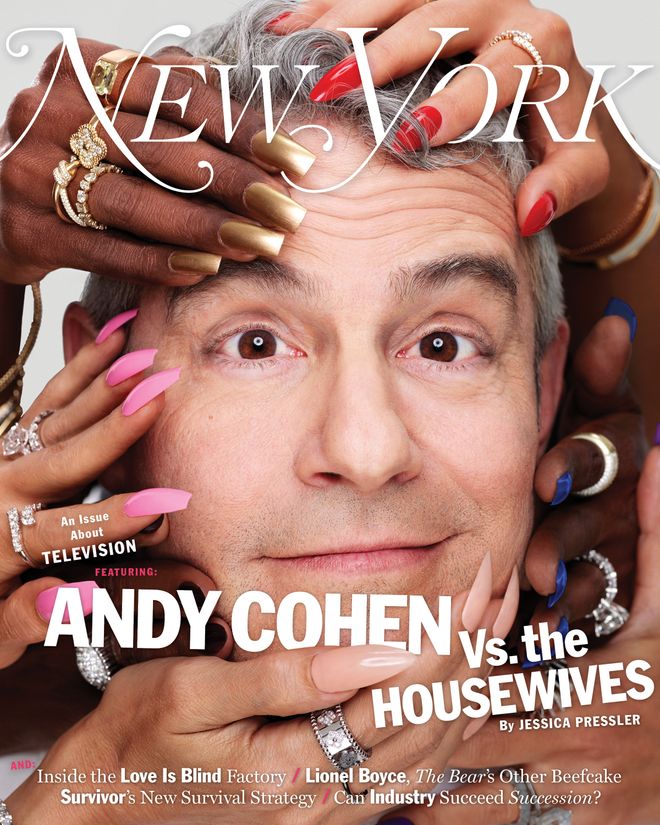

This article was published on June 5, 2024. The Bear has since received 23 nominations for the 2024 Emmy Awards, including an Outstanding Supporting Actor nomination for Lionel Boyce. Read all of Vulture’s Emmy-race coverage here.

When we go to eat something, people will now look to me like, ‘What should we get?’” Lionel Boyce tells me over cheeseburgers and fries at the packed S&P luncheonette in Flatiron this spring. S&P has his favorite burger in the city, originally recommended by a friend during one of the actor’s trips to New York. Because he has starred for the past two years as pastry chef Marcus Brooks on one of television’s most popular dramas, FX’s The Bear, about the inner workings of a Chicago restaurant, his dining choices now carry an air of authority. “And then I pick something and everyone’s like, ‘I don’t like this,’” he says, laughing. “I’m like, ‘Well, I don’t know.’ It’s still me. It’s not like I’m a seasoned chef.”

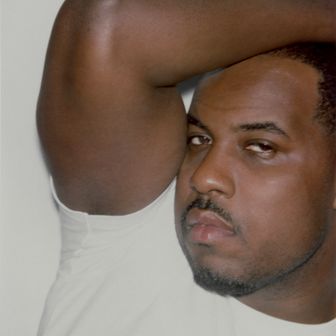

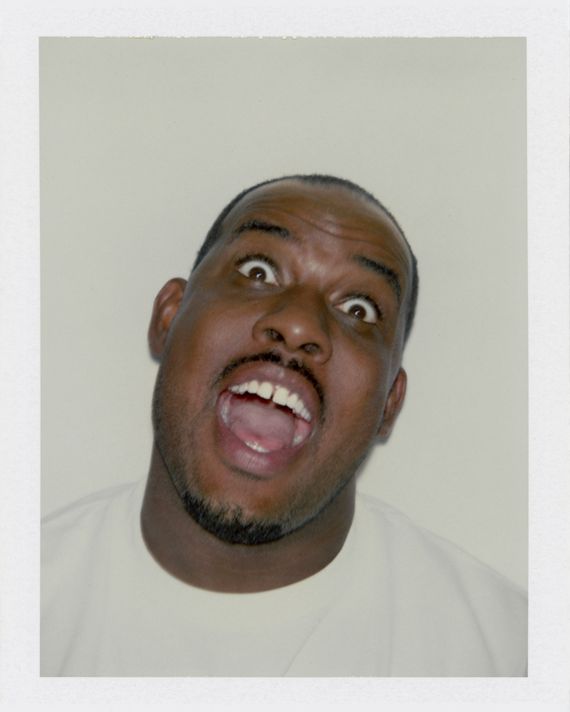

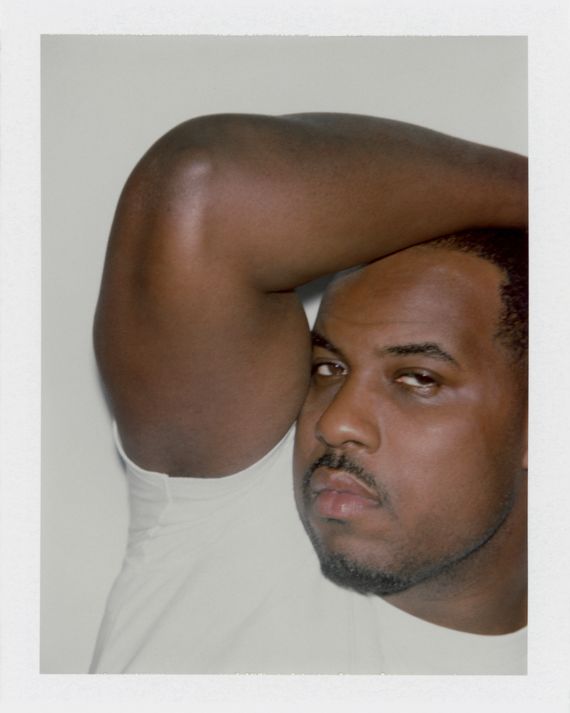

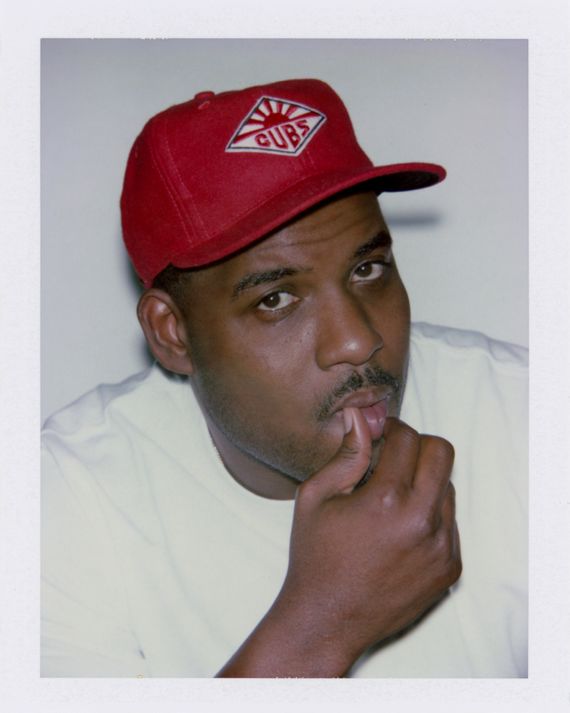

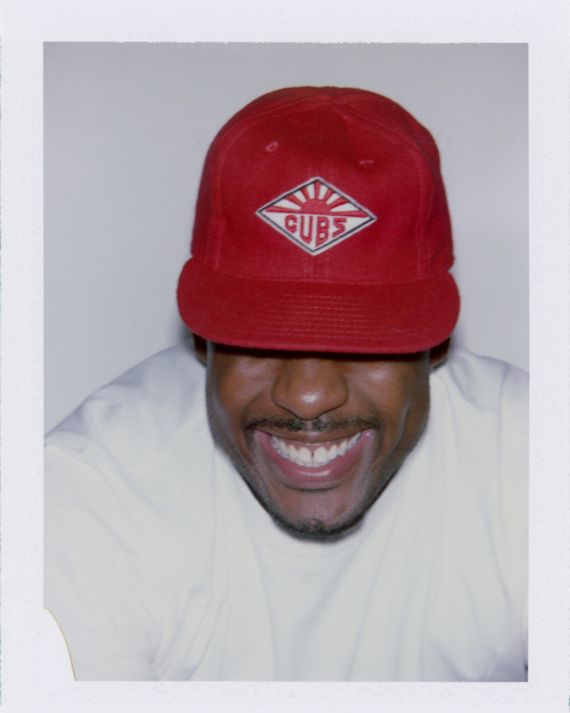

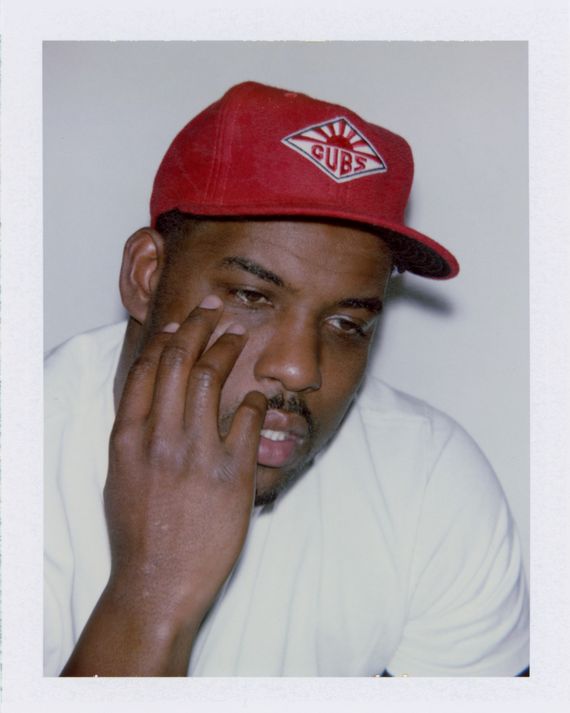

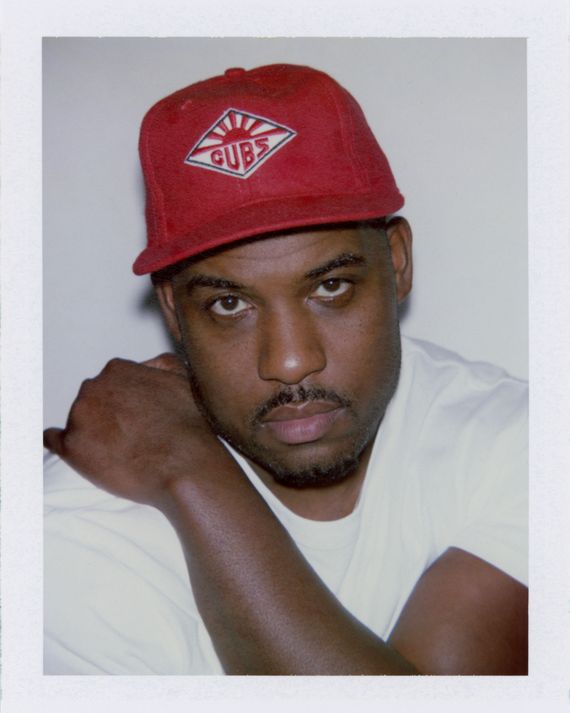

At around six-foot-three, Boyce is perched higher than most at the old-time diner table. He’s in a gray short-sleeved tee, green cargos, Dunks, and a navy cap that reads TOKYO across the front in orange felt. The 33-year-old speaks in hushed tones, sometimes at a nervous speed. Much like his character, the mild-mannered Marcus, Boyce is usually the calmest person in a crowd. Marcus is a man of few words; when he does speak, it’s sincere and with purpose. He’s quick to help co-workers navigate tumultuous relationships with one another, and in his off time, he helps care for his mother, who’s in what appears to be a coma.

In This Issue

More From

the Television Issue

See All

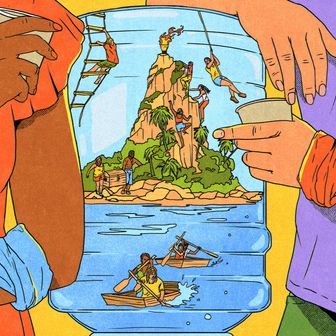

Not until season two does Marcus start to feel more like a main character, in large part owing to Boyce’s performance in “Honeydew,” his most prominent appearance on the show so far. In the episode, directed by Ramy Youssef, Marcus is sent to a professional kitchen in Copenhagen by his boss, Jeremy Allen White’s Carmy Berzatto, to help him gain confidence. The task at hand? To study under a big-time British-born chef named Luca and acquire the tools that will help him invent three desserts before the show’s titular new restaurant opens. At one point, we see Marcus scrambling to Google dextrose because he has been charged with making shiso gelée, a dessert infused with flavor from a well-known Japanese herb he has never heard of. Minutes before, he is fucking up at placing flower petals atop a fancy pudding with chopsticks. “Sorry, I’m a little nervous,” he says. “I think at a certain stage it becomes less about skill and it’s more about being open,” Luca offers after Marcus asks how he got so good. “To the world, to yourself, to other people.” It’s a captivating depiction of someone discovering an unexpected passion. It’s also largely Boyce’s own life story.

He grew up in Inglewood, California, the second of three children. His father was an Arrowhead Water delivery driver, and his mother was an L.A. sheriff and a devout Christian. When she wasn’t working, she was listening to talk radio or watching T. D. Jakes sermons on TV. “She always says she missed her calling as an orator,” Boyce tells me. “The kind of characters I like are similar to my mom. Someone who very much stands on their own ground, very larger-than-life characters. Like Will Ferrell or Danny McBride types.”

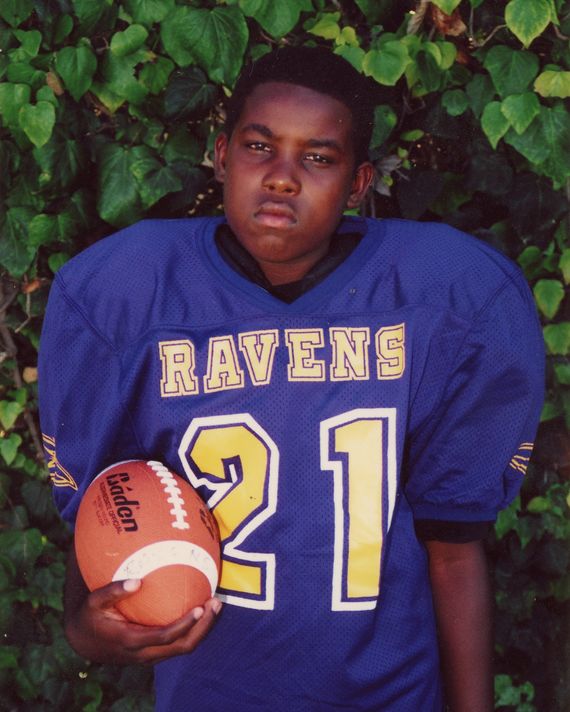

In his early years, Boyce was similarly boisterous. He played basketball and football and was on the track team, and he never stuck to one crowd. In middle school, he started getting kicked out of class because he had “just discovered how to be funny” and disrupted lessons to get jokes off. Outside sports, he experimented with constructing new story lines for his favorite TV show. “I wanted to understand the link between Black people, kung fu, and anime,” he remembers. “Like every young nigga, I just watched Dragon Ball Z and started to write episodes of it, making up stuff.” Around the beginning of high school, he grew more reserved. “I actually don’t remember the transition when I calmed down,” he says. He made football his primary focus and briefly left his script-writing passion projects behind — until his senior year, when he enrolled in a drama course and reconnected with an old classmate from elementary school.

“I met that nigga in first grade at a fucking private school in Inglewood, but he didn’t remember,” Tyler, the Creator tells me, laughing into the phone. “And then when I saw him in 12th grade, I walked up to him like, ‘Hey, you went to First Church, huh?’ He’s like, ‘Yeah, how’d you know?’ I was like, ‘Because I could never forget that moisturized skin color you got, brother.’ And he was like, ‘What the fuck wrong with you?’ But it’s true.” In the class at Westchester High School, their relationship grew from small talk and dapping each other up in the hallways to connecting over their love for Chappelle’s Show, Napoleon Dynamite, the Wayans brothers’ Scary Movie franchise, and Adult Swim. A drama-class prompt assignment in their high school drama class deepened their bond: They were instructed to build a story by writing in two-minute intervals with a partner; after the two minutes were up, one person would pass the script to the other, who would add on to what came before. “When I read it, I noticed that, although it was random, our antennas were matching,” Tyler says. “The jokes we gravitated to were different — I was more absurd, over-the-top, and he was so sniper. Very laser-specific. More toned but still outrageous in its own way. And that’s where we clicked.”

By 2009, that last year of high school, Tyler and his rap collective, Odd Future, were already establishing themselves in Los Angeles’s underground youth culture, releasing group mixtapes, performing, and dropping skate videos on YouTube. Boyce started to hang out with Tyler’s crew, people like Jasper Dolphin and Travis Bennett, who, like Tyler, reveled in juvenile debauchery and havoc wreaking — an early-’90s-baby take on Jackass except with Black teenagers from the West Coast. After graduating, Odd Future would bulldoze their way into the mainstream, establishing arguably the most impactful artists’ camp of their generation. Musically and stylistically, the collective (which included Earl Sweatshirt, Hodgy Beats, Left Brain, Syd, Domo Genesis, and Frank Ocean) meshed the sensibilities of hip-hop and punk culture.

In the meantime, Boyce was a weakside linebacker for El Camino College in

Torrance, hoping to play well enough to transfer to a Division I program. Tyler had been telling him since high school that he was going to make a television show in the tradition of Dave Chappelle’s and, when given the chance, Boyce would have to be a part of it. In 2011, Tyler called him into an unexpected meeting with Adult Swim, which ended with the creation of Loiter Squad, an over-the-top sketch-comedy series involving gags, original characters, and celebrity parodies. Boyce would write and act in sketches. It was promising enough for him to leave his football dreams in the rearview. He was also appearing more regularly in Odd Future’s output under the name L Boy. On “Hi,” the intro for the collective’s 2012 released The OF Tape Vol. 2, he sets the tone by cracking on every member of the group with unhinged outbursts: “My nigga Earl ugly as fuck! Let’s have a moment of silence for that nigga real quick.”

“I grew up around so much high energy that if a person comes in with a lot of it, I’m not disturbed,” Boyce says of the group’s antics. “They can go to a hundred, and I won’t be like, ‘Get the fuck away from me.’ I get it. My brain is just always running, so I can keep up with wherever they’re going.” If you squint and scan the screen, you’ll see a young Boyce in the background of the “Oldie” video laughing and dancing while Frank, Earl, and Tyler command the camera’s attention. “Loiter Squad was like kicking the door open. I had assumed I would play sports my whole life,” Boyce says as we leave S&P and walk toward Union Square Park.

On the show, Boyce came off as stiffer than his contagiously goofy friends, but his deadpan performances provided a different brand of humor, something more like putting your not fully committed brother up to a prank because you know people will take him more seriously. One of the funnier skits was almost exactly that: Boyce posted up in various parts of Los Angeles, taunting people walking down the street while his homeboys — and Bam Margera — feed him lines through a microphone. His best role in Loiter Squad was Catchphrase Jones, a ’70s-blaxploitation-inspired, Mr. T–esque soul brotha with a bushy mustache who chases around a villain named the Black Claw, speaking only in ridiculous puns at random moments. “In hindsight, it was crazy,” Boyce reflects. “We didn’t know how far it was reaching or what it really meant to other people because I was just so excited by the idea of working with Adult Swim. If you don’t know how hard it is to get something made, it’s not hard because you don’t know what you’re up against. You’re not considering anything other than, We’re doing it.”

Loiter Squad ran for three seasons between 2012 and 2014. “We started getting a handle on how to actually execute our ideas during the third season,” Boyce says. “We were headed to a point where it would have been funny to five people.” When it ended, Tyler pulled Boyce in to co-create The Jellies!, an animated sitcom that also aired on Adult Swim and had an even more neurotic sense of humor. “The Jellies! was like, ‘Do we have to make it a little bit more accessible because our humor is really stupid? No, you lean into it.’”

After Loiter Squad, Boyce realized he liked being both in front of and behind the camera. “I thought, How can I do more of this?” he says. The Bear is the first major role he landed from an audition. Reading the script, “you could feel what you see in the pilot, the pace of it. And Marcus made sense to me.”

“The funny part is Marcus was actually written for Lionel, and I’m not sure how much he knows that,” says Christopher Storer, the show’s creator, writer, and director. The two met through Boyce’s close friend Jerrod Carmichael and television producer Nick Weidenfeld years before working together; Storer says from early on, he was struck by Boyce and his friends’ creative output. He was also impressed by how much Boyce’s commitment to film came through in their conversations. In The Bear’s first season, his character feels underdeveloped; Marcus’s evolution in season two is stark, a product of Boyce’s increased comfort in the role and having the trust from Storer to expand it. “Lionel has such a sensitivity and intelligence to him,” Storer says. “In the coming seasons, you see him pass that information he’s learned on to other people.”

In just two seasons, the show, which also stars Ayo Edebiri, Ebon Moss-Bachrach, and Matty Matheson, has won ten Emmys (for its first season alone) and four Golden Globes. Boyce is expected to earn his first Emmy nomination this summer for his performance in “Honeydew.” Twelve years into the game, he’s just starting to get over the feeling of being a fish out of water in certain spaces. Earlier in his career, he says, “I would be making excuses to discredit myself from everything that I’ve made. I’d be like, ‘I helped make this,’ instead of, ‘I do this.’ I think it was because my path was nontraditional.” He doesn’t feel that when playing Marcus. His gradual ownership of the role is perhaps why people identify so strongly with his character. In a sub-Reddit for the show, a fan kicks off a discussion with “Marcus gets like no love despite being a total sweetheart and completely dedicated to his craft. He’s handsome, sweet, loves his mom.”

The will-they-won’t-they relationship between Marcus and Edebiri’s chef Sydney has inspired a collective yearning in viewers for even a bread crumb of resolution. Occasionally, Marcus breaks out of his shell to flirt with Sydney, whose emotions are harder to read. In season two’s finale, when Marcus feels rejected after sort of asking Sydney out, he grows frustrated and snaps at her in front of the team for something completely unrelated. “I think the show did a good job of exploring this thing where you get along with a person and sometimes feelings get crossed. You’re not really sure. It’s like, I like this person, but am I supposed to like them more?” Boyce says. “I guess I don’t really think about it. To me, I’m just wherever the story goes as long as it makes sense. People have already made up their minds of what they think and want.” Some fans want to see Sydney with Carmy, the blue-eyed, physically fit white dude who’s in charge of the place — so much so that Edebiri and Allen White’s IRL relationship is being overly emphasized in the press. Sydney never feels closed off to the idea of something deeper with Carmy. Marcus, though, is a Black man presented as an affable, gentle giant who is easier to friend-zone because he’s never shown in a romantic light.

“I think there’s some really lovely and powerful moments between Sydney and Marcus in season three. They connect because they’re such similar people who are really excited about what they do,” Edebiri says. “Sydney can’t put that excitement down just because of everything that she’s been through, and seeing it again in Marcus allowed her to feel it again. We got to do some scenes together that I’m kind of nervous to see but excited.”

Whether or not something happens between Marcus and Sydney, Marcus is due for some significant changes. The last time we see him, after the rush of the restaurant’s soft launch, he picks up his phone and finds he has missed repeated calls and emergency texts from the nurse who cares for his mother. In March, photos of the show’s cast dressed in black on the steps of a Chicago church leaked online, all but confirming his mother’s death. How will such a crucial loss affect the character going forward? “Over the last two seasons, we sort of see the way grief affects people in the restaurant, whether it was in their past or something they’re currently going through. And I think to have Marcus begin to wrap his mind around that and start to face it, we want to show, well, what’s his version of that?” Storer says.

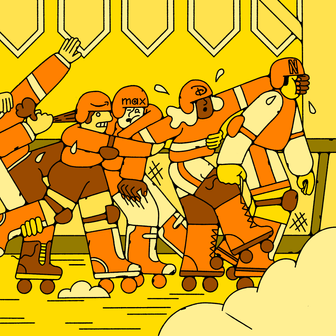

The roles Boyce is securing outside of The Bear don’t yet carve out a clear path of what kind of actor he may become, and that’s what’s exciting about this stage of his career. He appeared as a home-and-garden-store clerk in the final season of Curb Your Enthusiasm this year; he and Larry David have a funny standoff about why the place doesn’t sell Black lawn-jockey statues. “That’s a scenario I’ve daydreamed about. You can’t really fathom it,” Boyce says. It’s the only role he has auditioned for outside of The Bear. “You’re doing a scene with Larry and he’s making the faces you’ve watched for like 15, 20, however many years. I’m like, This is wild. No dream’s a farce now.” In February, it was announced that Boyce will star in a new Max Minghella–directed psychological thriller with Kate Hudson, Elisabeth Moss, Arian Moayed, Este Haim, Kaia Gerber, and Ziwe.

After filming for The Bear’s upcoming season, out June 27, wrapped last month, Boyce returned to his home in L.A. These days, he’s trying to pin down a solid routine that will let him get back to writing projects with friends like Tyler. He centers himself by regularly doing calisthenics workouts — just for cardio since weight lifting makes his already -broad frame too bulky, too quickly. He also has a love for chess; he plays against people on his phone almost every day. “There’s this crazy rush you get when you play a stranger,” he says. How often does he win? “A lot. Maybe it’s just I’m playing people who aren’t really that great.” When he realizes we’re within walking distance of the Chess Forum, a shop that sells chess pieces and hosts games, he suggests we make our way there. I warn him that he probably won’t be getting that crazy rush today, as I have very limited knowledge of the game. He offers to teach, just as he taught Tyler.

The Chess Forum, near Washington Square Park, feels like a store in a film with regular business handled in the front and underworld matters handled in the back. It’s a tight space. To the right of the front desk is a throughway that opens up to six small tables; three of them are occupied with games of varying skill levels. “Pawns, first row. They usually move one space forward,” Boyce says, demonstrating before breaking down the rest of the game for me. I feel like I’m experiencing the inverse of Marcus and Luca in “Honeydew,” learning the tricks of the trade from someone far more skilled than I who extends the grace of patiently and attentively walking me through the process. I get the sense that Boyce lives for these teachable moments regardless of which end he’s on.