It was time for Walter Prince to make his choice. The 25-year-old had spent the previous six hours on a Dating Game–inspired set, complete with a rainbow-striped backdrop and a white shag rug, filming an episode of the YouTube dating show Proof of Love. He and three other guys had competed for the heart of the jumpsuit-clad bachelorette Ali Diamond in a series of increasingly absurd challenges — a rap battle, a hot-plate cook-off, a birth-preparation session with a doula — and Prince had prevailed. Now the moment had come for him to decide whether to go on a date with Diamond or take a $3,000 check and walk away.

“It’s a tough decision,” Prince said, hanging his head under his black Yankees cap. Diamond waited expectantly, arms outstretched. “Ali, I’ve loved getting to know you and cooking for you and, like, being fake pregnant with you,” he continued. “But — I gotta take that cash.”

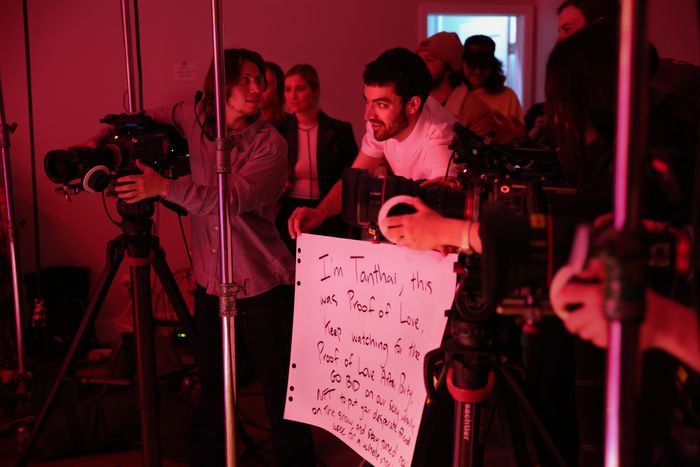

Tanthai Pongstien, the show’s host, dropped his flimsy prop mic and ran a circle around Prince, dashing toward the camera. “Let’s fucking go! Oh, shit!” Pongstien screamed, his voice going hoarse. “He rugged her! He fucking rugged her.”

That’s cryptospeak for scammed — and Prince’s cash will be rendered in ethereum. It was a Wednesday night in Greenpoint, and we were at the studio–cum–office space of Mad Realities, a collective of eight core team members and 437 NFT holders, which its founders call the world’s first crypto-powered production studio. Every week since early March, Mad Realities has been shooting episodes of Proof of Love, funded by more than 172 ETH (currently worth about $505,000) that the founders raised through the sale of NFTs. Those NFTs came with the right to vote on major decisions like casting every week’s new bachelor or bachelorette as well as the show’s 24-year-old host, who runs two UX/UI-design agencies. “I’m here for clout. I’m here for the vibe,” Pongstien said. “But this is also a way to kick-start my entertainment career.” He claimed he could not name a single reality-TV show.

In the minds of many people in this room, crypto could be the savior of a broken entertainment industry — and Mad Realities could be the savior of an insular crypto universe. Co-founders Alice Ma, 26, and Devin Lewtan, 23, as well as Mad Realities head of creative Adam Faze, 24, think these kinds of shows could resonate beyond group chats and Tech Twitter. As Ma put it, they want to “permeate the culture. Like, legitimate culture.”

The show’s premise is simple: At the end of every taping, the winning contestant can choose to go on a date with their newly beloved and come back for the May 1 season finale, where they’ll compete for a jackpot currently worth about $15,000 (to be paid in ethereum, of course) — or they can choose a nontrivial sum and walk away. The show’s pacing is staccato, riddled with onscreen graphics and memes, courtesy of editor Ari Cagan. “The internet is so serious sometimes, especially Crypto Twitter. Everyone’s very focused on making money,” said Lewtan, who’s also Mad Realities’ CEO. “We wanted to create a space for real people to come on and lean into the bit.” And besides, she said, “traditional Hollywood is not keeping up with the times.” Ma and Lewtan thought a Web3 dating show would be the kind of thing that’s just weird enough to get people talking. It hasn’t happened quite yet: The most-viewed episode just cracked 6,000 views.

On set, vapes of various makes and substances were surreptitiously hit by their streetwear-clad owners. A couple of guys passed around an Oculus headset like a joint, playing a fishing game in the metaverse. The studio pulsed with the energy of 20-somethings drunk on the feeling of being in charge — as well as being literally drunk: A folding table that once supported a tidy row of liquor bottles was now littered with half-empties.

“Usually there’s someone in the room who’s a 50-year-old executive who funded the thing,” said Ma. “So you kind of have to be PC in certain ways, or you can’t curse, or you can’t make certain jokes that might be considered brand damage to them. We really get to do whatever we want with it.” For contestants, the team scoured its networks for the most outlandish mutuals they could find — people like Prince, who, arriving on set, told me he was “fiscally 45, physically 24,” and during his on-camera confessional said he was looking for someone to, “for lack of a better word, suck the soul out of me.” When I asked him what he did for work, he described himself as “a clout-chaser.” (He also works at a text-message marketing company.) So far, he’s been the only contestant to choose money over a date.

The fact that they would know someone like Prince isn’t surprising: Ma was a core contributor to ConstitutionDAO, the group of “degens” that tried to buy the Constitution last fall. Faze did a brief stint in the film division at Annapurna, but he’s probably best known for appearing to be the ex-boyfriend of Olivia Rodrigo. (Despite copious paparazzi evidence, neither confirmed their relationship.) Lewtan, a former product engineer at a software company, was one of the women behind “NYU Girls Roasting Tech Guys,” a COVID-era Clubhouse dating show she and her co-founders called a “bar simulation” when they launched it last year. Another NYU Girl, Sarah Jannetti, now runs Mad Realities’ operations. Unlike on that Clubhouse show, crypto — and crypto shilling — are integral to Proof of Love. Even the show’s name is a play on the blockchain terminology of “proof of stake” or “proof of work,” which are different mechanisms used to verify new transactions. Since contestants are mostly drawn from the teams’ social networks, many skew toward crypto enthusiasm. “Buy our fucking NFTs!” Pongstien yelled into the camera.

I already had. Right around the time Eric Adams announced he would take his first three mayoral paychecks in bitcoin last fall, I became intensely curious about crypto. I started buying a few NFTs, and in January, I purchased one of Mad Realities’ “Genesis Pass” NFTs, an animation of a floating rose, for around $300. I soon found out that the boundaries in crypto are porous: It’s the kind of place where founders will freely up-bid their own auctions and anonymous Twitter trolls can make value fluctuate with the stroke of a keyboard. I opted to sell my Mad Realities NFT before publishing this story, asking the same amount I had paid for it; it got snapped up less than four minutes later.

It’s hard to say whether Mad Realities is really aiming to disrupt Hollywood or if this is just another tech start-up, one looking to capitalize on the enormous amount of money flowing into the crypto space. It’s possible that a Kickstarter and a group chat could yield the same results. “It’s funny because our YouTube views are like, fine,” said Faze. “But in person, we have this community of people that are like, ‘Oh my God, it’s Mad Realities Sunday.’” A few days after the shoot where Prince took the cash, the Mad Realities team hosted an episode premiere and panel at the NFT gallery Bright Moments in Soho. More than 250 people showed up — nearly double the venue’s capacity — and formed a line outside. The ground was littered with rose petals, a nod to Mad Realities’ NFT graphics. A waitress circulated with a tray of shots. Butterfly clips abounded. One woman wore a show-stopping zebra-print set; Prince showed up with a date wearing an oversize black chain hanging from the back of her jeans.

These people were clearly not all here for the blockchain. Even for those who are actually in tech, the real attraction of crypto is the community. The inside-joke terms (rug pull, HODL, WAGMI), the general ridiculousness, the high barrier to entry both in terms of knowledge and finance: It’s all making the internet feel small again, at least for a subset of people. At the after-party, I was approached by a member of Friends With Benefits, one of the most well-known crypto social clubs. (It’s also one of the most maligned, in part because it can cost the equivalent of thousands of dollars to join as a full member.) “At the end of the day, this is a project to get acquired by someone,” the crypto bro said of the Mad Realities show. “If any NFT project is about to get swallowed up, this is what that is. Proof of concept.” Then he threatened to sue me if I used his name in this story.

Mad Realities’ founders imagine Proof of Love could be a silver bullet, the thing that will finally get the outside world to understand crypto’s potential without the crypto stigma. But the reality is that the world of crypto is still volatile and poorly regulated: Over one weekend in January, the price of bitcoin plummeted, taking with it $130 billion. Also there’s not much stopping someone from setting up a project, selling NFTs, and running away with the money. (It’s happened more than a few times, and the DOJ is just starting to catch up.)

Even at a small scale, Mad Realities’ chaos has occasionally veered out of the founders’ control. During each week’s episode premiere, the team auctions off an NFT that is a unique edition, which is called a 1/1. The winning bidder gets a producer credit, sponsorship rights, and the power to cast anyone they want as a contestant in the next episode. The week I visited the set, Ma, Lewtan, and other members of the core team were dealing with a crisis involving the most recent winner: After this person had secured their 1/1, they went on a satirical Twitter rant about wanting to send an unhoused person to compete on Proof of Love to “prove that house-free people are just as sexually desirable and hot as other groups, if not more.” In response, the bachelorette, Diamond, threatened to quit, outraged at the idea of someone “using a houseless person as a prop.”

The 1/1 winner turned out to be trolling. Even so, the team had to scramble, responding to feedback and denouncing the tweets while trying to get a protocol in place to vet people nominated for the show. “We thought the chaos was going to be more like someone deciding to send a gift to a contestant. We have very thoughtful, kind people in our community,” Lewtan told me. “Even just jokes like this, associating with our brand … I mean, it’s top of mind.” For the first time, they were confronting what could happen when you let strangers bid on creative control. If they weren’t prepared, Lewtan acknowledged, “This could turn dystopian very quickly.”