She’s composed and imposing,” says Margo Jefferson. We’re gazing at a painting in “Before Yesterday We Could Fly,” a one-room installation at the Metropolitan Museum of Art that takes the history of Seneca Village — a community of free Blacks who thrived in Manhattan during the 19th century — and flings it into the Afrofuture, conjoining and collapsing time altogether. On this day, Jefferson is lithe in draped layers, a thin scarf around her neck. Her hair is cropped, her blonde curls impeccably toned; her hands swan through the air as she speaks. Before us is Henry Taylor’s large-scale portrait of Andrea Motley Crabtree, the first female deep-sea diver in the U.S. Army. There is evidence of staging in Crabtree’s ramrod pose, her orderly, unthreatening ’fro, her carmine-painted mouth. Hers is the practiced, stolid ladyhood requisite for all Black mavens, all defiers of the limitations imposed upon their race and sex. She wears her diving suit. She holds her helmet on her knee. “She looks impermeable — but you know she’s not,” says Jefferson.

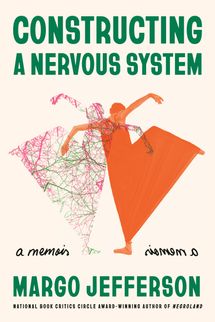

It’s a summation typical of the Jeffersonian critical manner. This month, the writer publishes her second memoir, Constructing a Nervous System, an exploration of the self as told through the lives of Jefferson’s late sister, Denise; artists like Ella Fitzgerald and Ike Turner; and literary figures such as Willa Cather and the character Topsy of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The book is a double helix of personal history and critique — a work built on the nearly half-century Jefferson has spent as a critic of American culture, writing on traditions from minstrelsy to contemporary theater, literature, and music, buttressed by racial pathos all. She published her first essay, “Ripping Off Black Music,” in Harper’s in 1973. The opening shot: “Elvis Presley was the greatest minstrel America ever spawned, and he appeared in bold whiteface. He sang like a nigger, danced like a nigger, walked like a nigger, and talked like a nigger. Chuck Berry, unfortunately, was a nigger.” Jefferson was 26 years old. “I wanted to make my way to the center of American culture and find ways to decenter it,” she has said — and she did, winning a Pulitzer Prize as a New York Times critic in 1995 and writing the book On Michael Jackson in 2006 before turning to memoir.

The critic Hilton Als started reading Jefferson in the ’70s, when she was writing for The Village Voice and editing at Newsweek. He calls her one of the best literary critics working. “I would say that she has a certain restlessness with form. That restlessness, that constant evolution of and beyond any constraints, is what I admire most about her,” he says. “There are writers who try to keep ahead of the times. I’ve always felt that the times have to try to keep up with Margo.”

On the page, her sentences are balletic. They do not sweat. “I was taught to avoid showing off,” she begins her 2015 memoir, Negroland. Yet she tells me that politesse, ingrained by her “haute bourgeoisie” upbringing, was a habit she sought to shake. “There was a certain well-behaved manner even when I was arguing, standing firm, that I didn’t want to stay in thrall to. I was talking about this with a student of mine the other day” — Jefferson teaches at Columbia — “who was Black and was writing about race. And I said, ‘There are moments where you are very good. But you are working a little too hard to be reasonable and obliging, to make it something that your audience will be able to move toward. I don’t want you to do exactly the opposite, but look at what this is doing.’ ” Jefferson laughs. “So now transfer this back to me: ‘Margo artfully switched it to a student!’ ”

Jefferson’s people are a people of many names: the Black/Negro aristocracy, the Black/Negro elite, the Black/Negro bourgeoisie, the Talented Tenth, the blue-vein society, the third race, Jack-and-Jillers, Oreos here, impostors there. They have been subjects of satire (Darryl Pinckney’s High Cotton), literary fiction (Dorothy West’s The Wedding), sociology (E. Franklin Frazier’s Black Bourgeoisie), creative nonfiction (Lawrence Otis Graham’s Our Kind of People), and poetic lambasting, when, in 1926, Langston Hughes derided their “Nordic manners, Nordic faces, Nordic hair, Nordic art (if any), and an Episcopal heaven.”

Despite this, their existence remained contested. “Is There a Black Upper Class?” queried the Times in 1999. This was owed to their insularity and, as Jefferson has said, their absence from the awareness of white American society. A fear of transgression pervaded the Black upper classes of Jefferson’s childhood, a neurotically clannish sect obsessed with appearances and achievements. Her turn toward memoir — long considered the province of egoists, turncoats, and women — could be read as a rebellion. “Children always find ways to subvert while they’re busy complying,” Jefferson writes in Negroland. “This child’s method of subversion? She would achieve success, but she would treat it like a concession she’d been forced to make … She came to feel that too much had been required of her. She would have her revenge.”

Margo was born in Chicago in 1947, younger sister to Denise. Their mother, Irma, was a homemaker and society woman. Their father, Dr. Ronald Jefferson, was head of pediatrics at Provident, a Black hospital on the city’s South Side. Theirs was a world of firsts and onlys. The girls attended the University of Chicago Laboratory Schools. Margo went on to Brandeis, then Columbia. Denise — whom Margo calls “forceful, very lively, sometimes obstreperous” — pursued a career in dance, eventually becoming director of the Ailey School at the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater.

The Jeffersons were one of few Black families residing in cushy, historic Hyde Park. The neighborhood of the University of Chicago now boasts a butterfly sanctuary, the Museum of Science and Industry, a shopping center, and the Obama family residence, a stone’s throw from the Isidore H. Heller House, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. It is an island of comfort amid poverty, with Englewood nearby. “It’s a strained-for oasis,” Jefferson tells me. “But still an oasis.” It is also brutally maintained: The University of Chicago boasts one of the largest private police forces in the country.

Growing up there was a plural experience that could find expression only in hybridized form; it feels as if Jefferson, looking about and seeing no suitable models, decided to construct her own. Negroland homes in on these dramas with her sister cast as both dramaturge and lead actress. Constructing a Nervous System is a cultural memoir in the same vein, a topography of Jefferson’s many selves. The book begins on a stage — one she saw in a dream. (“It’s a big writing challenge to make one’s dreams work on the page,” she says. “I’ve seen it fail enough times that I wanted that challenge.”) Its pages are full of swings, digressions, delights, with Jefferson acting as tour guide through her intellectual and cultural landscape. She calls it cultural memoir, temperamental memoir, temperamental autobiography. Handed to her by the poet Wendy S. Walters over dinner, the title gave order to the assemblage, one the author feared would not gel: “I was afraid of a certain disjointedness. It was a struggle to make it all cohere — I worried about losing the reader.”

Among the book’s prevalent themes is Jefferson’s reality as an “adult orphan.” Her father died in the ’90s. Then, in 2010, her sister died from ovarian cancer. This premature death imbued Jefferson with a sense of urgency, an awareness of time’s frailty; it was the event that hastened her need to document her upbringing in the fear that the particular milieu was disappearing. (“Secrecy about family, about what went on in the domestic household was a bond between us — was part of what made us family,” writes bell hooks. “There was a dread one felt about breaking that bond.”) Before Jefferson could publish Negroland, her mother died too. Jefferson and I speak of the peculiarity of the term adult orphan — its similarity to adult children and how both terms feel oxymoronic but aren’t. I ask Jefferson whether, like me, she considers “daughter” to be one of her primary identities. She says she does.

“THRUM go the materials of my life,” she writes in Constructing. “Chosen, imposed, inherited, made up. I imagined it as a nervous system. But not the standard biological one.” For her, that includes her lifelong obsession with performers — specifically, male performers. Jefferson became active in the feminist movement of the 1970s. At the time, she appeared alongside people like Ti-Grace Atkinson and Kate Millett in the documentary Some American Feminists, expounding on the double binds and particularities of Black women’s situations and how the feminist, leftist, and Black-liberation movements had each failed them in turn. “I’ll never renounce the pleasures the feminine has always given me: its materials, its histories, its small rituals and grand designs,” Jefferson writes in the new book. “And yet, since my teens, I’ve avidly (often secretly) collected black male performers as alter egos. I admired, I longed to possess their styles. To wield them.”

What made her most anxious about publishing the book was her inclusion of Ike Turner. (Or, as she calls him, “the Pygmalion-tyrant who launched potent Tina Turner; pushed and beat her till she fled, then remade both of them: her as a superstar, him as a disgrace.”) She deeply admires Tina, whom she calls “masterly” and thinks deserves a better documentary than the one she got last year. Still, Jefferson has always envied Ike — for his looks, charisma, and presence. “I knew it was a risk,” she says. “I knew people would say, ‘You’ve got some goddamn nerve.’ ”

But for better or worse, Ike Turner is one of the figures constellating her universe, of which Constructing is an attestation. She roams through the crevices of her mind, through its makings, fixations, and perceived shortcomings. The writing moves among first person, second, third. In any other hands, the fear of disjointedness would be justified. As a reader, I find Jefferson most enrapturing when — as in her debut Harper’s essay — she bins her gentility for something sharper. Tending her envy, tallying slights both personal and historical, indulging her gloomier moods: the well-comported girl no more.

“When I was in high school, even through college, I toyed with the idea of being an actor. And I was not good at assuming other characters and other voices. I wasn’t. I was kind of a personality gal, right?” Jefferson says now. “So I’d sometimes tell myself, Okay, you’re doing this in writing, you’re invoking. That’s how you found a way to do this: to be a kind of character actor.”

Want more stories like this one? Subscribe now to support our journalism and get unlimited access to our coverage. If you prefer to read in print, you can also find this article in the April 11, 2022, issue of New York Magazine.