The re-emergence of singer Marianne Faithfull in 1979 was one of the most striking second acts in the history of pop music. For her album of that year, Broken English, she collected a suite of songs that mapped out a corrosive, unsparing and highly personal journey through some of the 20th century’s most toxic realms — celebrity and heroin addiction, sexism and self-destruction.

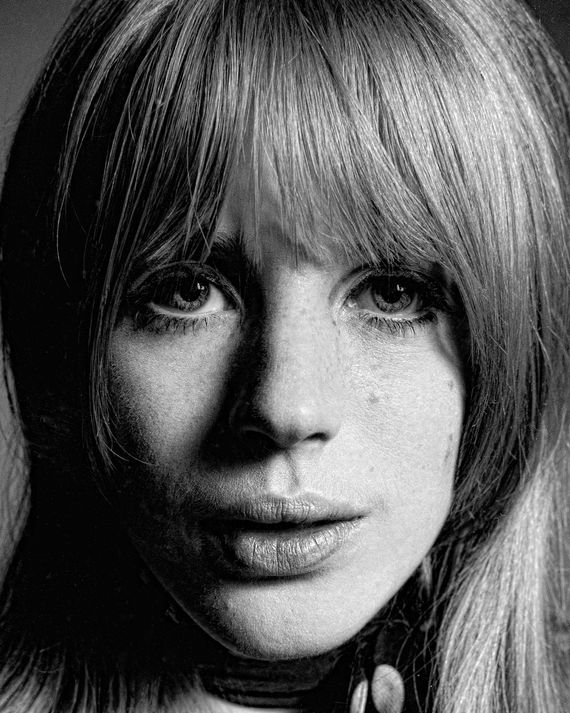

Faithfull was a beautiful pop star at the height of the ’60s rock era, known across the world for her hits (notably the classic ballad “As Tears Go By”) and her boyfriend, Rolling Stone Mick Jagger.

A few years later, she was a homeless drug addict.

Broken English made it clear that Faithfull, whose death at 78 was announced today, was a remarkable artist in her own right, and something quite different from the mere caricature of the beautiful muse on the arm of a rock star at his decadent height. The album was unsparing — a bleak tour through a nightmarish pop-culture fun house. The music was shimmery, sometimes abrasive, sometimes almost Eurodisco. In “The Ballad of Lucy Jordan” she took a portrait of an emotionally isolated housewife and turned it into a riveting portrait of female anomie, with intimations of suicide. The title song captured the singer’s own continental background with overtones to the Baader-Meinhof terrorist group. And on “Why Ya Do It,” she focused rage and humiliation into a profanity-laden dialog that spoke savagely for every woman humiliated by a man:

Why’d ya do it, she said, when you know it makes me sore?

’’Cause she had cobwebs up her fanny and I believe in giving to the poor’

Why’d ya do it, she said, why’d you spit on my snatch?

Are we out of love now? Is this just a bad patch?

As the album and her 1994 autobiography, Faithfull, however, she was at pains to make clear she was a woman who acted and was not acted upon; together they are a tough portrait of the dead-end freak-show carnival where, Faithfull freely admitted, she was the ringmaster.

Faithfull’s family history is some concoction of the Felliniesque and, you might say, the Schnitzlerian, after the guy who wrote Traumnovelle, the book on which Stanley Kubrick based Eyes Wide Shut. In her autobiography, she writes that her mother, a dancer and an actress, came from a family of moneyed Austro-Hungarian aristocrats, and was properly called the Baroness Erisson; her mother’s granduncle was Leopold von Sacher-Masoch, who wrote the early erotic classic Venus in Furs and became the eponym for masochism. She says her mother, Eva, was badly damaged during the Second World War but also met a British major who was working for MI6. (His name was Glynn Faithfull; she did not invent “faithfull” for her pop career.)

He came from a line of odd people — Faithull writes that her father’s father was a “sexologist” who had invented a “frigidity machine” to “unlock primal libidinal energy.” Her mother did not enjoy sex, and her father was obsessed with it. “Eva presumed she was going to be pampered and adored,” Faithfull wrote, “the last thing my father wanted in a mate. He wanted a co-conspirator with whom he could share his vision.” The family ended up living in an almost communal social-research institution. After her parents, inevitably, split up, she and her mother were reduced to poverty, made worse by her mother’s eccentricities. Faithfull, who was not Catholic, ended up going to a convent school.

Eventually Faithfull found an interest in performing in plays and, entranced by Buddy Holly and Joan Baez and Simone de Beauvoir, folk music, and arty café intellectualism as well. On a trip to London, she ended up at a party at Cambridge; there she met a student named John Dunbar. He came from an eccentric background, too, and soon Faithfull was living with him and his family. “It was like a whole doorway opened up into a world that I didn’t [know existed],” she said.

It was 1964 — on the eve of what came to be known as Swinging London, where, after nearly 20 years of postwar blues, a somewhat unshackled band of artists, entrepreneurs, hipsters, refugees from an impoverished upper class, the wealthy aimless, and a new breed of pop star were in the process of revolutionizing Western society.

One of Dunbar’s friends was Peter Asher, the son of a wealthy lawyer. Asher, too, still lived at home with his parents and his sister, the model Jane Asher. The Asher parents were continental in the same way the Dunbars were in that they let their daughter bring her boyfriend, Paul McCartney, home to live with them.

They soon all became part of a perfervid scene. Dunbar and Asher — with money the latter had made from having a pop hit called “A World Without Love,” written by McCartney — opened a bookshop with an art gallery in the basement. (In 1966, the Indica Gallery would host Yoko Ono’s first exhibition in London. As every Beatles fan knows, Dunbar would invite his friend John Lennon to come see it for the VIP preview before opening night.) With Dunbar one night in 1964, Faithfull attended a party where she met the people who would change her life.

From that point, two tales would diverge. One would be her own story, which would take her through a world few get to experience but in the end would leave her living on the streets scrounging for drugs. The other story, which is the one that made up her media image, was a highly sexualized and male-centric one. That story is generally told this way, in a typically overwrought passage from Old Gods Almost Dead, Stephen Davis’s biography of the Rolling Stones:

Conversation died when Marianne walked into the room. Girls like her, Scott Fitzgerald wrote, “do all the breathing for everyone, and finally even the men have to go outside for air.” She was a dreamy vision of Anglo-European drop-dead beauty: long blonde hair, eyes like blue ice, a “large balcony” (as the French call big breasts), and full, inviting lips plumped like downy pillows. Marianne was also educated, well read, and highly intelligent, and her innocent gaze fell on a man like a heat wave.

In Rolling Stones lore, Faithfull overnight became the Stones’ muse. The reality was different. At the time, the boy-men of the band were still creating themselves; Faithfull said that she was dismayed that night by Jagger’s scruffiness. She was, however, impressed with the band’s manager, a maelstrom of ambition, fast talk, and relativistic ethics named Andrew Loog Oldham.

As much as anyone, Oldham’s precocious perceptions as to where the culture was moving — and the opportunities open to those who took advantage of it — helped make the Rolling Stones the sensation they became. Dunbar said that Oldham saw Faithfull as “an angel with big tits” — a new image for the ambitious visionary to promote in an outlandish new world. He soon took Faithfull into a studio with Lionel Bart, who had just written the score for Oliver! She recorded a Bart song for her first single, then, for the B-side, the tune Jagger and Keith Richards had written. She sang it in mono in front of an orchestra. (A young session guitarist named Jimmy Page played the guitar part.) It was called “As Tears Go By,” and it was apparent to all that it was not a B-side.

“I didn’t think anything would come of it,” she told Gillian Gaar, author of She’s a Rebel: The History of Women in Rock and Roll. “It came out in the summer, I did a few TV shows, and that was all very boring, and I thought, Oh God, this is a big fuss about nothing. And I just went back to school in the fall.”

Oldham thought otherwise: “In another century you’d set sail for her, in 1964 you’d record her,” his advertising copy read. The song ultimately became a top-ten hit in England, then went to No. 22 on the American charts. It would take Jagger and Richards more than a year to find appropriate songs for themselves to sing, but somehow they had managed to write something close to a standard on one of the first tries. As Faithfull later noted, “It’s an absolutely astonishing thing for a boy of 20 to have written. A song about a woman looking back nostalgically on her life … It did such a good job of imprinting that it was to become, alas, an indelible part of my media-conjured self for the next 15 years.”

She kept making hits — four top-ten singles in the U.K. — and put out two albums, one of pop songs — featuring “As Tears Go By” — and another of the folk music she had more affinity for. The latter is uneven but also contains a lovely take on Ian & Sylvia’s “Four Strong Winds.”

At 18, she was living in a house filled with junkies living off the largesse of her and her husband. She was still a pop star — a typical week might include singing “Yesterday” with Paul McCartney on a TV special — and spent money like a pop star, too. (Dunbar said her first addiction was shopping.) But she was soon pulled away by a gateway to a darker world: the grass-infused, highly untidy abode that Rolling Stone Brian Jones and Anita Pallenberg used as their base of operations.

Jones was the iconic but fragile secret musical force of the Stones; Pallenberg was the epitome of the elegant, mysterious Swedish muse. (She spoke four languages.) “Anita and Brian were like two beautiful children who had inherited a decrepit palazzo,” Faithfull wrote. “Every day they would dress up in their furs and satins and velvets and parade about and invite people over, and we would all sit on the floor.” In Faithfull’s telling, Jagger hit on her when they happened to meet again at a recording studio — to get her attention, he tipped his wine down the front of her shirt. Still she remained more connected to other members of the band. She spent her money with profligacy, schemed with the beautiful Pallenberg, and gazed longingly at Keith Richards.

One memorable evening eventually included a fumbling but ultimately failed make-out session with Jones, then (finally!) a rousing early-hours lovemaking session with Richards. The next morning, Jagger invited her out shopping, and that put them on the trajectory that ultimately solidified their relationship.

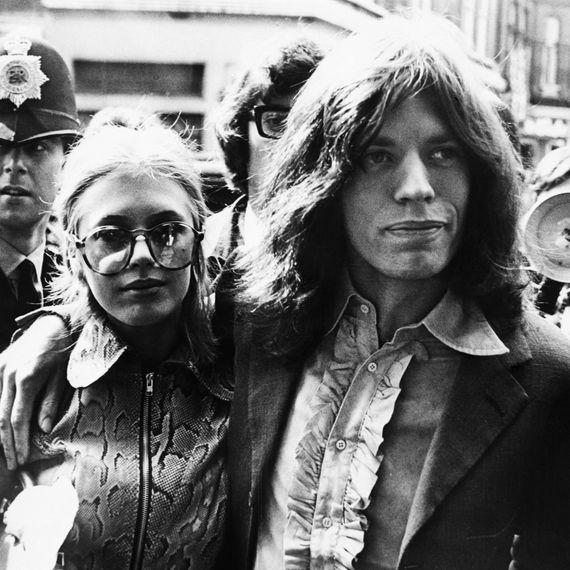

It was at the start of a connection with the star that turned out to be real and lasting — she was with Jagger only until 1970, surprisingly enough — and took her through the band’s most tumultuous years; early rock stardom fueled by precocious and sharp-tongued social comment; the drug bust that nearly destroyed them; the decline and pathetic death of Jones; then the band’s magisterial cultural apogee and its arguable artistic high point, the album Let It Bleed.

She and Jagger were the glamour couple of the day, their life full of trips to Morocco, world tours, debauched wild parties at the homes of this or that Getty or Guinness heir. But the parts of her life that were real, like losing a child with Jagger to a miscarriage, were glossed over by friends and ignored by those who wanted an upbeat beauty on the rock star’s arm. She began to view her world in a more detached and reportorial way, seeing fabled events in their banal reality, as when she accompanied Bob Dylan on tour:

Dylan went into the room where the Beatles were sitting all scrunched up on the couch, all of them fantastically nervous (for once). Lennon, Ringo, George, and Paul, and one or two roadies. Nobody said anything. They were waiting for the oracle to speak. But Dylan just sat down and looked at them as if they were all just total strangers at a railway station. It wasn’t so much a matter of being cool; they were too young to be genuinely cool. Like teenagers, they were all afraid of what the others might think and simply froze in each other’s company.

Dylan made a pass at her, too, and after she declined, she got the full brunt of his petty acrimony. And there were so many other moments like that: Jimi Hendrix whispering in her ear to dump Jagger and run off with him … Backstage in Bristol while Tina Turner teaches Mick to dance the Sideways Pony … Writing “Sister Morphine” with Jagger … Trooping along with the Beatles and Jagger to the London Hilton to sit at the Maharishi’s feet … Naked with Jagger in bed, as Allen Ginsberg came to visit and discussed Dante and the Marquis de Sade … at Abbey Road as the Beatles constructed the climactic end to “A Day in the Life” …

… And then, finally and most fatefully, driving off the morning after that event for a weekend test-drive of a new strain of acid at Richards’s country home, which would result in a famous drug raid that nearly put both Richards and Jagger into prison, and forever change her image in Britain.

The arrests were part of wide-ranging Establishment attacks on the new generation of pop stars in Britain at the time, done through connivance with informers and a hostile conservative media. Faithfull was at the center of it; after a day doing acid and playing on the beach, the group had come back to Richards’s Redlands estate. Faithfull had no extra clothes, so she bundled herself up in a white fur rug — and it was attired like this that she watched as a band of police came in to arrest the party for possession.

The media sensation that followed had everything, including sex, courtesy of Faithfull. “NAKED GIRL AT STONES PARTY,” ran a front-page headline. Keith Richards tried to put what she was wearing in perspective — “in fact, Marianne was quite chastely attired for once” — but the event obliterated her angelic image and gave her a new one drenched in drugs and kink. (Beside the implication that she’d been the group’s weekend plaything, there was also a made-up story about her using a candy bar as a sex toy.) “Mick and Keith came out of it with an enhanced bad-boy varnish,” she told the BBC many years later. “I came out of it diminished.”

Ironically, the pills Jagger was arrested for were Faithfull’s — she’d left them in the jacket months before. Jagger gallantly took the blame, and in a few months both he and Richards were convicted. Only an unexpected withering editorial from the Times of London — with the headline “Who Breaks a Butterfly on a Wheel?” — helped turn public opinion around, and the convictions were later overturned.

She also seemed to have a sense of disquiet about who and what she was, perhaps exacerbated by the loss of the child she and Jagger had been looking forward to. Her breakdown took several years, particularly after heroin slowly drew her in. She acted a few times, including credible roles onstage in Chekhov plays and in a well-reviewed production of Hamlet. During the latter, she says, she began snorting the drug during every show, giving a realistic cast to Ophelia’s decline. She claims that she was, in I’ll Never Forget What’s ’is Name, the first actor to say “fuck” in a mainstream movie. She also starred in the existential psychedelic film The Girl on a Motorcycle (retitled, not very subtly, Naked Under Leather in America), which features a few polarized sex scenes — and ends badly for the title figure. She released a single of “Sister Morphine,” her song with Jagger; reaction to the scandalous subject got the record removed from stores by her label, and created another furor. The Stones put it on Sticky Fingers without incident. Then came the disintegration of Brian Jones, once one of her best friends, now debilitated with drugs and insecurities. Pallenberg (whom Jones often physically beat) abandoned him; he was forced out of the Stones, and died soon after. Living this dual life — her own and as a rock god’s muse — was, it appeared, beginning to destroy her. In a high-rise hotel room looking out over Sydney Harbour, she had her own Ophelia moment, and tried to get a window open to jump. She couldn’t, she wrote — so she took an overdose of pills. She ended up in a coma for six days. A stint at a psychiatric rehab unit in Switzerland didn’t help.

She was all of 25.

She would find herself at the dinner parties that were the focal point of her and Jagger’s social life — and nod off during dinner. Most notoriously in Stones lore, she carried on an affair with Keith Richards’s drug supplier in exchange for heroin. In time, disgusted with herself, she drove Jagger away. In one scene, she described overhearing the head of Atlantic Records, Ahmet Ertegun, insistently tell Jagger that his junkie girlfriend was a liability to the Stones’ future. She had to agree: “I wanted to be a junkie more than I wanted to be with him. That was my idea of glamour!” Jagger has an outlandish reputation when it comes to women, of course, but accounts from that era all credit his devotion to Faithfull. She herself takes the blame as well: “I was all the trouble.” Impervious even to the strains of Jagger’s most aching love song, “Wild Horses,” written for her, she left.

Her descent was Dantean, but set in a candy-colored milieu. She carted off her child and became engaged to an aristocratic intellectual without letting him know about her drug problems. This was made somewhat easier by the fact that the couple chose to live apart, with their respective mothers. The relationship lasted nine months.

From there she spent all her money, vaporized her career, and burned every bridge she could. Allowed to stay at one last friend’s home even through months of unspeakable behavior in front of virtually everyone else she knew, she fell asleep in the bathtub with the water running and nearly destroyed the house.

Yet absurdist echoes from her onetime status still chased her. In 1971, she was in Paris in a tryst with her dealer — and then had to pack up and leave with him abruptly. (He’d been supplying Jim Morrison, and the Doors singer had just OD’d and died.) Then she appeared in Kenneth Anger’s famous, but ridiculous, underground film Lucifer Rising.

“Even as inept as Kenneth was,” she wrote, “I knew he was dangerous in a way. I knew that simply by being in the film I was involving myself in a magic act far more potent than Kenneth’s hocus-pocus satanism. Smearing myself with Max Factor blood and crawling around an Arab graveyard at five o’clock in the morning as the sun rose over the pyramids was absolute insanity. To be that passive, to let someone like that make me perform a ritualistic act of such ghoulish proportions, was just mindless. If I’d been my normal self I would have just laughed, but by then I was a hopeless junkie.”

From there, she took up residency against a wall in an abandoned lot in Soho. She shrank down to 90 pounds and eventually only survived by getting on a National Health Service plan that supplied her with heroin. Along the way she lost custody of Nicholas to her ex-husband. Once in a while a friend would try to help her and get her into a rehab clinic. “I stayed a day and a half,” Faithfull wrote of one such opportunity, “and while I was there, supposedly detoxing, got someone to smuggle in some smack for me and got punched out for it by my male nurse, losing my two front teeth.”

Her addiction lasted more than 15 years. Given her celebrity status, her life was weirder than that of most homeless junkies. Once in a while she would be brought in by a well-meaning person to record an album or film a movie, but she always ended up back in the streets. (While most of her work in this period is unmemorable, she did record a persuasive album, to be titled Masques, that was rejected by her record company. It was released in the 1980s as Rich Kid Blues.) An eight-month cure — again courtesy of the NHS — brought her back to life for a time. She might bump into David Bowie, and end up singing “I Got You, Babe” with him dressed in a nun’s outfit. She saw Jagger and his new girlfriend at a party, and even had a rendezvous with Dylan after Broken English. But she always drifted back into dependence. She had remade her name (and made some money), but in the end it was just more opportunities to crash again, including a dreadful Saturday Night Live performance in 1980.

Broken English was a revelation to many, a scorching horror show articulated by a woman whose very voice told her story. Her knowing but still sweet English folkie’s voice reverted to her Germanic roots; it was full of cynicism and caricature, like a junkie Angela Lansbury; rasped with cigarettes and much worse, it spit out invective, regret, and dissolution by turns. Incredibly, Faithfull was only 33, but she sounded old — the living embodiment of a decayed Brechtian anti-heroine.

In a classic Behind the Music episode, this would have been the end of her dependence. Instead, it went on for another devastating seven years. Only then did she really clean up for good, after which she re-emerged, again and for the last time. Beginning with Strange Weather in 1987 — a dark cabaret in which she finally embraces her Teutonic voice in a set of fairly controlled performances — she released more than a dozen albums. As Faithfull reconstructed her life, she became in her an elder stateswoman of cool, sometimes photographed with her old pals — Mick, Keith, Anita — and sometimes in other contexts, like a full page ad for the Gap shot by Herb Ritts, or playing the role of God on an episode of Absolutely Fabulous. (Pallenberg was the Devil.)

She recorded the appropriate things, like an album with superproducer Daniel Lanois and two albums with duets with acquaintances old and young. The first was Easy Come, Easy Go, made with Hal Willner, the late producer known for his distinctive high-concept compilation albums. It even included a song with Richards, on the Merle Haggard classic “Sing Me Back Home.” The second, Kissin Time, featured songs she co-wrote with everyone from Nick Cave to Beck to Billy Corgan. Her final releases were Negative Capability, in 2018, and, after a close scare with COVID in 2021, She Walks in Beauty, in which she sings some classic British poetry over the songs of Warren Ellis.

Of these later albums, Give My Love to London is a good place to start; the title song has a rousing beat, an Irish lilt, and a sense of times passed:

I’ll see all the places

I used to know so well

From Maida Vale to Chelsea

From paradise to hell

Paradise to hell, boys

Paradise to hell