Only so many add-it-to-my-tabs can keep a girl comfortable in a bar like Bemelmans on a Friday night. The piano man is thrashing at his keys, but it’s really a waste of time; everyone is sloshed, and the crowd — a blur of wedges, polos, and pastels — suggests a midsummer bacchanale for permanent Hamptonites. “I love that about New York — everyone’s having a situation,” says Marlowe Granados, the 29-year-old filmmaker and artist whose debut novel, Happy Hour, will be published by Verso on September 7. That may be so, but the chances of baptism by martini are simply too high in here tonight, and no sooner had we entered did we seek refuge back in the Carlyle’s lobby.

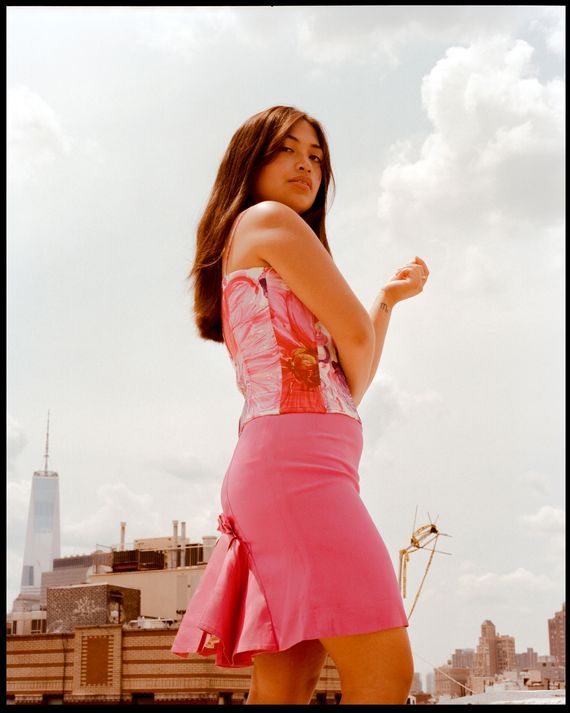

Granados — who wears a black slip and Fendi sandals that click-clack as she walks — slides her ponytail aside to take a sip of her French 75. She is gap-toothed with a jaw that makes her look haughty, although she is not, and big black eyes that glint in the light of the fake fireplace. She is soon approached by a very sunburned woman. “Sorry to interrupt,” the woman interrupts. “I just love your bow, your outfit, and you’re beautiful.” She says this almost reverently, then leaves, only to be replaced by another admirer. This happens so many times it starts to feel like a setup, until — as though to one-up them all — an old man with two dirty white terriers tries, as a flirty joke, to steal her purse. It’s a little alarming, and he finally returns it with a hysterical laugh. He wears tattered joggers and a Rolex. Later, the porter informs us that he lives here.

The whole scene could have been raw material for Happy Hour, a book full of sugar babies, aristocrats, and other outrageous people — some fictionalized, others composites from the author’s life. Its heroines are Isa and Gala, two 20-somethings with no money and appetites for opulence, both of them determined to spend their summer in New York doing “absolutely nothing.” For a while, they get away with it, charming their way into the city’s well-to-do circles. The glamour starts to dim when rent money gets scarce, pushing the girls into jobs as life models and hostesses. If “charm is currency,” as the author puts it, then Happy Hour is concerned with its use and depletion, and Isa, whose diary we’re reading, is still learning how to manage it.

Granados’s ability to underpin the story with wry class commentary without shoving it in a reader’s face is what caught the eye of Cian McCourt, head of fiction at Verso. “Marlowe doesn’t tax these women with trauma,” he says, “but she’s also wise to the mechanics of society, its structures and its failings, and this buttresses every interaction in the book.”

The protagonists of Happy Hour fall into a clear literary tradition. They owe something to Holly Golightly and Eliza Doolittle, as well as the heroines of Elaine Dundy, Edith Wharton, and Anita Loos, whose romantic exploits are fortified by sardonic observations of the moneyed social planes they move in. Isa even talks like them; indeed, Happy Hour is practically written in a transatlantic accent. (Granados also co-hosts a movie podcast called The Mean Reds.) The writer jokes that Isa’s distinctive, Old Hollywood way of speaking is really her own “after three drinks.” The inflection is the product of the years she spent in London, studying creative writing at Goldsmiths. “It’s embarrassing for me,” she claims, but she really seems to relish it; as the night goes on, “I have to pee” does turn into “I’m going to use the loo.”

Certain aspects of the novel suggest that Granados had another muse: herself. Both she and Isa are mixed, Filipina and Salvadoran; have best friends named Gala; and lost their mothers as teens. Still, Granados is coy about how much is fiction and how much is autobiography. “Love is in some ways like fascination,” Isa muses in the book. “The thing about fascination is once you realize there is nothing left to discover, it quickly wears thin.”

Granados grew up in a suburb of Toronto in a two-bedroom apartment with her young, divorced mother. When Granados was a teenager, her mother traveled four days a week for work, but her job still remains a mystery to her daughter. “Honestly, there was a time where I was like, maybe she’s a spy,” she says. As a girl, she spent a lot of time with her grandparents, who put her on a diet of classic Hollywood cinema and indoor activities.

The author’s “party-girl phase,” from which many of Happy Hour’s events were lifted, began when she was 15. Her family had little money, but, like Isa, she spent her teens being “flown out” to various European destinations. She suggests that some of these youthful adventures were incidental, but it’s not hard to see that Granados has a history of ambition — like when, at 18, she took a bus to New York to get one of her scripts made. And she has always worked: appearing in commercials and music videos, modeling, and photographing everything. “I was flown out to Berlin — no, Zurich — to attend a birthday party of this weird man, who was literally turning 19 or 20.” The man wanted her to take pictures, she remembers, but he also just wanted her to be there. “Sometimes men just fly you out,” she says with a shrug.

Granados describes her own life as “very Pygmalion.” She’s always moved through posh spaces, armed with intelligence and mannerisms picked up from books and old films, and she’s always felt a kinship with what she calls the “architects of women” — flappers, adventuresses, geishas, and other members of the demimonde who have used wit and charm to rise in the ranks. Happy Hour is written in the image of those figures. Isa and Gala are granted access, and an ephemeral kind of class status, by their ability to enhance other people’s experiences. It’s when Isa starts to tire of this that Happy Hour begins to ask questions — what kind of women have to sing for their suppers, and what happens to them when they stop?

Granados started writing Happy Hour at 22 and finished at 25, calling the period after its completion her “lost years.” These were marked by a broken engagement and a series of bad boyfriends, underpinned by a string of professional rejections. At the same time, her agent was shopping the book, the Me Too movement kicked off, and publishers wanted stories about how hard it was to be a woman. But nothing bad really happens to Isa and Gala, and that was a problem — one that says a lot more about publishers than it does about Happy Hour. (It was eventually put out by Flying Books, a small Toronto bookstore and imprint, before getting picked up by Verso.)

While the book may be masquerading as party-girl literature in the vein of Eve Babitz, its protagonists lack the privilege usually inherent to those stories. The girls don’t have the luxury, as Babitz once wrote, “to forsake this dinner party and jump into real life”; real life is around the corner, whether they like it or not. Neither of the girls are living in the U.S. legally, a fact made most apparent when Gala (who, it is briefly mentioned, “was a baby refugee, you know, Bosnian War”) must suffer a dog bite because she has no health insurance. Vegetables are out of budget; they subsist on bodega hot dogs and pizza. And while both are bona fide party girls, Isa, who is brown, is always careful. Meanwhile, Gala, who is white, “is allowed to be wild and reckless” and relies on Isa to pick up the pieces.

None of this is in your face, because none of it is the point. “If you know, you know,” says Granados. “These girls are experiencing misogyny, racism. I wanted to have it in there without spelling it out.” These tensions come to a head when Isa visits the Hamptons at the behest of a British aristocrat. “It was clear I would be Singing for My Supper,” Isa writes at the beginning of the trip, but when she refuses, she’s shoved into an attic room away from the other guests. Her host later introduces her as a “gypsy,” then assigns her a series of errands she feels too indebted to refuse.

Back at the Carlyle, things are becoming sordid. A man marches out of the bar, vomits on the marble flagstones, and leaves the building, whispering “sorry” to Granados, whom he’d splashed a bit. Granados suggests we go to Balthazar and we hop in a cab. As we proceed to dinner (oysters, escargot, steak tartare, much bread), Granados realizes she lost the back of her earring in the car. She appeals to the Balthazar host for some sticky tack. “I have none,” he says, looking baffled. I suggest a pencil eraser and the host offers Granados a Ticonderoga. She rips the eraser off and sticks it to the back of the giant, crystal-and-gold orb on her right ear. She “hates” not wearing earrings.

Last year, Granados released her first short film, The Leaving Party, a pretty, meandering picture that follows a dozen young women through a summer’s day. The film touches on the same passions that make up Happy Hour: femininity, friendship, and, most important, glamour — that “illusive, hard to define, yet identifiable” quality she’s spent a lifetime perfecting. She has no plans to be a lifelong “authoress,” and she’s straight-faced when she says her only goal is to improve her posture.

“I knew people treated me differently growing up, and I felt uncomfortable, but I had no words for it,” says Granados. “I’ve always felt a little bit — not ostracized, but not taken seriously. And I always thought that was so funny, because it was based on what? That I was young? That I was pretty? Or that I was … whatever. It’s like, ‘Who’s going to have the last laugh now?’”

Balthazar is empty now. Things have a dreamy haze, the result of Champagne and dry contact lenses. The restaurant feels a little frozen in time. I wonder, if Granados could go back in history, where would she go? “Oh, that’s easy,” she says, tossing her head. “I would go to Studio 54, and I would have to be let in. And I would be a muse, of course.”