Karl Ove Knausgaard is one of my literary heroes. This distresses many of my female, queer, and trans friends: Torrey, you have every woman writer in the world available to admire, but you won’t shut up about a tall, handsome Nordic-dad dude who spends five pages explaining how to turn on a stove? Guilty.

The stereotype of the Knausgaard fan is of a thwarted literary man eager to tell you about his own idea for a systems novel, but there are many of us out there who don’t fit that description and are obsessed — to the exasperation of our loved ones — with a writer best known for an epic six-volume work called My Struggle (yes, the same title as Hitler’s memoir; yes, it’s intentional). In private, we indulge our vice by spending hours analyzing every little aspect of his character, speculating on what he meant by this or that section, on whether he really is as good a writer as we think he is, especially when there’s so much opinion to the contrary. I’ve gone on a Knausgaard bender with a young gay black man and an Australian grandmother — together. I’ve encountered Knausgaard obsessives who work for the government. In Hollywood. I’ve met them at a queer separatist compound.

Knausgaard has become a byword for a certain kind of autofiction, a putatively fictional style in which the author details the self and the people in their orbit, occasionally resulting in scandal — as was the case for Knausgaard himself after he wrote bracingly and perhaps invasively about his father’s death, his then-wife’s bipolar diagnosis, and his crush on a student. For me, a trans writer, Knausgaard taught me about writing shame as liberation from it — a literary version of the kind of emotional breakthrough one normally experiences in therapy. Knausgaard, who is Norwegian and lives in London, famously edits very little, doesn’t plan his books in advance, and doesn’t even believe in “craft,” that ubiquitous dogma of the American M.F.A. program. Instead, he just types and seeks presence, writing about anything and everything in that pursuit, like a soccer player who spends most of the game passing the ball around midfield, awaiting a moment of transcendent athleticism that makes all the tedium seem like a prelude to brilliance.

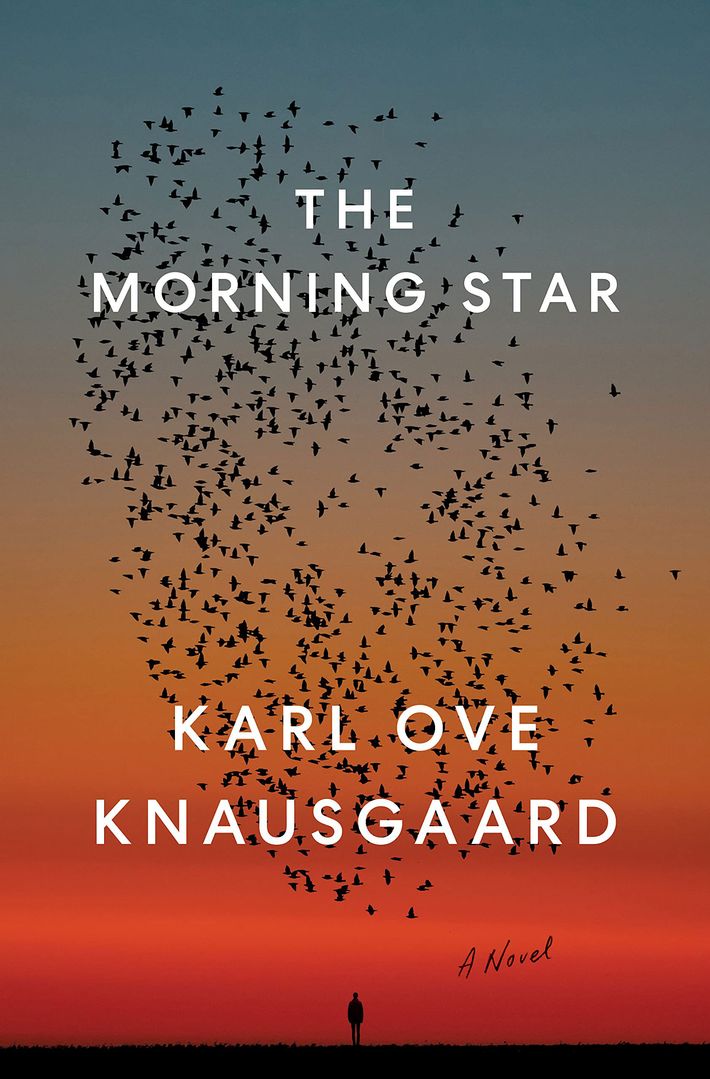

On September 28, The Morning Star, Knausgaard’s first new novel since My Struggle, will be published in the U.S., translated from Norwegian by Martin Aitken. The book is the author doing a 700-page Stephen King impression — in the sense that Bill Hader does an Al Pacino impression, where the point isn’t to look or sound exactly like Pacino, but rather for Hader to have fun. The Morning Star alternates points of view among nine Norwegians who find the mundanities of their lives interrupted by the appearance of an eerie new star that casts a twilight over the earth. Animals start behaving strangely; people known to be dead walk briefly among the living — and yet, for the characters in the book, everyday life must go on. Despite the emphasis on plot, this book is still Knausgaard being Knausgaard. It’s just that this time, he’s enjoying himself.

Why did you write this novel?

I wanted to do something very different from My Struggle. I wanted many voices, because in My Struggle, you have one voice and the whole world is in that voice, there’s nothing outside of that. In this book, I wanted the outside to be visible between the voices. Certain ideas have followed me up through the years, lots of subjects I haven’t been able to write about. When I started this novel, nothing was planned; all I had was an idea for many voices and for the star—the rest just came from whatever I had stored up.

Did the pandemic influence how you wrote it?

I wrote most of it during the pandemic, but I wasn’t aware of any connection at all. After the book was done, I began to understand that, yes, of course, it was influenced by the pandemic — not in any conscious way, but I had the very strong feeling during the pandemic that there was something out there, you know? Death, ambulances, masks, and gloves — something horrific, terrible. Early in the pandemic, you couldn’t leave the house, so that looming threat was external and unseen. Meanwhile, inside the home was just the ongoing domestic life of my family: the children making lunch, going to school online. That inside-outside contrast is part of the novel.

I heard gossip about this novel before you finished it: that it would be your take on Stephen King’s The Stand — many points of view on an apocalyptic event. That, like Stephen King, it would be fun. And it was fun, but even more, I felt like you were having fun writing it. Were you?

Yeah, I definitely had fun. My favorite novel for many years was Dracula, by Bram Stoker. I read and reread it when I was 14, and that kind of fiction I do really like, but it was … previously it was forbidden for me. I had forbidden myself to go there — where, if there is something problematic in a novel, you can just put in a demon or whatever.

Why did you forbid yourself from writing those kinds of novels before?

In those books, everything that happens in the world becomes a story, and something is lost when the world becomes purely story. In My Struggle, I wanted very much to be in the moment of presence, where there are no stories, before the narratives and stories take shape.

But then I have always loved fantastic literature: García Márquez, Borges, Calvino, Cortázar … I just thought I could never do it myself. I’ve always written about things very close to myself — one has one’s own rules and ways and restrictions. It’s like that in life, too; you can’t see your own restrictions because those restrictions are you. So this time, at first, I really tried to get out of myself. Then I realized, Okay, all the characters are still writing like me, thinking like me, so I tried to use them as vessels to take me to places I wouldn’t normally go.

Did you allow yourself to write a Stephen King–style novel because you’ve now had recognition on an international level? Because now if you solve a problem with a magic demon, no one is going to say, “Knausgaard can’t write”?

No! It works the opposite way! There’s all the pressure of expectation from people who liked the previous books. They will say, “Why should he write like this? Why can’t he just do the same thing as before?” My first novel came out, and I was 29, and I got the validation I’d wanted. But then I had to write a second novel, and I think it took me five years because I couldn’t write, just because of the pressure to follow up — because of all the external things that piled up in my head. I have learned to deal with it, to just say, Fuck it. I’ll do what I do, and I have to trust it. But still, it’s an enormous amount of doubt all the time. What’s expected of me has become the enemy. When you become conscious about how your books will be received, you’re a dead writer. It’s terrible.

And yet you had fun this time. The novel is about death. Why were you having so much fun writing about death?

I don’t think death is fun, so that’s not it. But I wrote an essay about death, and I realized that death had become very abstract in it, an intellectual play, a game I was enjoying — like death wasn’t real. I had to try to find a way to encounter the reality of death. And so I gave that essay to a character, Egil. I let Egil write the essay, then I sent him on a train ride to a situation where he had an encounter with death in the most horrible way. That was to take out the fun of it!

That essay closes the book in a way that reminded me of Tolstoy — how in Anna Karenina, Levin takes a hundred pages at the end to discuss a bunch of ideas that feel like they belong to Tolstoy himself. Is Egil your authorial stand-in the way Levin was for Tolstoy?

It’s funny mentioning Tolstoy because I read War and Peace the first time in an abridged translation from the ’50s or ’60s. Then a few years later, I read a new translation, and it was much longer. In the first one, all the things that didn’t have an epic narrative were gone because the editors thought, Oh, this is boring. But those bits make the book much richer. With them, you have the contradiction between what Tolstoy is saying in the essays — it’s like this, it’s like that — and then you have storytelling, which contradicts him and which goes in and out of his ideas. Reading it, you can’t really say what Tolstoy thinks. I like that dynamic. Having an opinion is very different from living or even writing a novel. When you write a novel, you’re not writing opinions; you’re exploring, on many levels, something you’re interested in.

Since you previously wrote autofiction, do you think that readers are trained to try to find “you” in your writing?

I have to forget that people will think it is me. In the new book, there is a character who drives drunk. Someone in my family asked me, “Why didn’t you tell me that you were out drunk driving?” But I have never done that in my life! It is like that with all of the characters, really. If people think it’s me, I can’t do anything about that.

It seemed to me you were playing with that expectation. For instance, the priest who tells Kathrine, “One must fasten one’s gaze.” That’s what a priest tells you, Karl Ove, in book six of My Struggle.

You have a good memory.

Then there’s the wife who’s struggling with psychosis —

I use everything I can and throw it in there. And many, many, many things from my life. That makes it authentic to me, because I need to believe in the characters. I need to believe that what happens in the book really happened — not in a concrete sense that it has to be fact, but the emotion must be authentic. That’s it. The character of Tove is a good example because something similar happened to me, but now it’s transplanted into this character, who is different from me but still has that same insight. Isn’t that how it is to write a novel, really? You use stuff you have and put it in. It doesn’t make the book you, but it makes it closer to you, so it’s easier to identify with it and lend it credibility.

Because I found many aspects of My Struggle in The Morning Star, I began to feel that you were creating, perhaps, a Knausgaardian version of a Marvel Cinematic Universe. Which feels also true to the genre. Like Stephen King, but also like David Mitchell, whose books share characters and a mythos across stories and genres. Was that in any way intentional?

It’s not intentional to make a Knausgaardian universe, no, but I have a plan for the universe of this book. Because when I’m writing, I am always in my own parallel universe that contains only and everything I know. My editor is a very literary man, and he really admires Stephen King. We spent a lot of time discussing whether or not to vary the voices of the characters, to move them into realms that aren’t mine, ones that I don’t know well. Or whether is it possible to have nine people who are similar in voice to the author. We decided that I shouldn’t work too much to make them different from me, with different language — otherwise, it would begin to lose credibility. Everybody knows I’m writing it anyway, so why should I pretend like I’m not?

What was it like for you to write female characters or priests — these characters who may be from the world you know but are still quite different from you?

The nurse, Solveig, was my first female character. I spent an enormous amount of time on her. At first, I restricted myself to what I knew for sure a woman would do or think, which left only things like: She’s drinking a cup of coffee; she’s looking at the tree. It didn’t work because it all was very stiff and unnatural. It was lifeless. Then I had to just not think about her as a woman. Just forget about that. When you write a character, you have some traits — that’s how it works — and then you start to write and then those traits take you in certain directions. You are on the course to something. I had to write Solveig the same way I had learned to write myself. When you write about yourself at age 16, you’re not a 16-year-old anymore either. When I started to do that, I don’t know if Solveig became a woman, but at least she became a person.

After I went through that wall, it became easier to write the other characters. Some of the characters I tried to put as far out as I could, like the culture journalist who hates culture. That was the most fun part to write. That’s a comic book; that’s a caricature, but it was fun.

One of the reasons I’m interested in your writing is that I love how you write gender, how you write masculinity.

Really?

Yeah, I’m trans, so gender is all over my own writing. Do you know the poet Eileen Myles?

No.

Myles is a famous queer poet in the U.S. who recently wrote in Bookforum, “I want fiction by ‘men’ in which they go into real detail about the internal mechanics of their own masculinity. I want evidence of that interiority on the page. Does it exist. All I’ve ever seen is silence or violence.”

When I read that, I was like, But Knausgaard has done that! He did it for 3,600 pages! In a single book! And more, I felt that you arrived at many of the conclusions to which queer and trans people arrive about gender, but from a totally different route. You show the constant work of masculinity, even in petty, mundane ways. For instance, in The Morning Star, when the character Arne notices himself getting a belly, he’s like, Well, a man should take up space. It’s okay that I have a belly because it’s not that I’m fat, which I believe would be unmanly, it’s that I take up space, which is manly.

Oh, that’s very interesting to hear how you read it. It is exactly like that with gender and manhood and what it is to be a man. That question runs through all of the different phases of My Struggle. I didn’t think about it in the same terms that you mention, but I think it was about who you are; it’s about identity and the roles available to you.

I was so wrong when I was 13, in terms of what others expected of a young man. I cried a lot. I liked clothes. I liked flowers. I liked to read. I was very much what’s considered feminine in the society I grew up in. And I was aware of it. I developed a double consciousness, where I saw both what was interior to me and how I was seen from outside. I saw both things at once. And that double consciousness is installed in the book. I wanted to be free, to become who I already was, but that’s impossible. You always have to fight between inside and outside expectations, but at some point, you don’t know which expectations come from inside you and which come from outside. To deal with it, you have to lock in your role, and it’s that locking-in mechanism I’m interested in. How I met it in different ways, at different times. I think that the mechanism to lock in my role got very strong when I first became a father. The feeling of degrading myself, almost of despair. What was that? Why was that?

Yes, these sound to me like very queer or trans ideas about gender but in totally different language than we use.

These ideas have been very important for me, but I have never seen it from that point of view. I never thought that someone would read it and see it in a new way. I tried to explore something from within in my own life. It is an incredibly important theme in the book because it’s constant and it’s ongoing. For me, literature is to try to reopen the things that are fixed … the things we have to fix for practical reasons, that are risky when they are unfixed. If it’s fixed, it’s easier — but that doesn’t only go for gender; that goes for almost everything, like worldviews and science and religion. But in real life, outside of ideologies, everything is floating and there are no borders. Only in writing and reading can you unlock what you previously locked in, and you can move around, and it is you and the richness of who you are. I’m happy you felt that.

Have you read much work by queer or trans writers?

No, not really. I have never actively gone for that. I don’t really know much about it at all.

God is a presence in the book, but so is evil, perhaps even the Devil, or Lucifer, otherwise named the Morning Star. In a New Yorker interview, you said that when a child asked you if you believe in God, you said yes. Do you believe in the Devil?

Well, not in the sense of [Peters holds up fingers like horns] … Not in that sense. But I do think it could be helpful to gather certain ominous things that are going on in the world into one figure or in one place and then investigate that. I feel that there is something threatening that’s going on in our time, and I’m trying to find a way to make that into a form that is very simple.

Your native country, Norway, features prominently in this book — the landscapes, the culture. Would you ever want to live there again, to reconnect?

No. At the moment, I would never go back to live there. I’m content living in London. I like new places, and a city like London will be new to me for another 20, 30 years.

I’ve been away from Norway 19 years now, first in Sweden and then England. I remember sitting in Bergen trying to write about Bergen was completely impossible — but living in Sweden, writing about Bergen was possible. It’s the distance that makes it possible. I do plan to write about London, but I can’t do it now … It’s just too fresh. Whereas Norway is in my fictional universe. Norway, to me, is a fiction. The landscape is a fiction. I don’t go back and check the details. Memory and writing are two sides of the same coin.

You have spoken often about your writing method: spontaneous, without a plan, without revisions. You’ve said this book is the first of a new series. How are you planning to write all these plot-driven novels without knowing where you’re going?

It is a bit dangerous for me to do because, as I work this way, I can’t know for sure how it’s going to turn out. The next book is almost written. And then the book after that, I just know some. I can’t tell you anything other than there will be another book in Norwegian this fall, a prequel. There’s going to be one every year.

The new one I’m working on, it’s very weird. I found 30 pages of a novel I began in 2011 or 2012. I had thrown it away. I thought it was so bad I didn’t show it to anyone, not even my editor. And then I found it recently, and I start to read it, and I said to myself, Well, this is quite interesting! Then I started writing it, and it grew to 700 pages, turning into something that I never expected.

Last question. This one has come up on the podcast Our Struggle, which has famous authors on to discuss pressing questions related to your book. You, Karl Ove, have often discussed eating tinned fish in your work. Is tinned fish — as some on Twitter have claimed — “hot girl food?”

Oh! I really don’t know about that.