The leaves are dropping, anxieties are spiking, and at the center of everything is a warbling uncertainty. Sit down. Read a book. Make your world as big or as small as it needs to be so you can power past whatever’s hunting you outside. This fall, we’re looking forward to books from Sally Rooney, Marlowe Granados, Venita Blackburn, Karl Ove Knausgaard, Asali Solomon, and more. Enjoy a delicious set of new realities to wrap yourself in like an itinerant quilt.

September

Marketing executive Kemi Adeyemi, flight attendant Brittany-Rae Johnson, and refugee Muna Saheed have almost nothing in common — except for the fact that they’re all Black women inextricably tied to one of the most powerful white men in Sweden. In her debut novel, travel writer Åkerström draws on her own experience as a Black woman living in Stockholm to create a rich narrative, weaving together each woman’s perspective to unpack nuances around foreignness and belonging. Through lively prose and spirited dialogue, Åkerström shows that for all the protagonists’ differences, being a Black woman in a white-dominated society will inevitably lead them to the same fate. — Mary Retta

This bifurcated collection of stories follows a cast of fictional protagonists as they navigate Black girlhood, in all its gallant and grisly manifestations. Part I revels in narratives of absence and absurdity: The Scorpio daughter of a Leo-Virgo-cusp mother learns discipline from her matriarch’s marital dysfunction, Barbie is diagnosed with PTSD, and a family’s food processing is financed with flesh. Part II, grounded by a tale of loss and young queer love, embraces diverse narrative mediums and flourishes: It opens with a grief log that records the data of depression and desire; it also features a crossword puzzle, a quiz, and an answer key. Blackburn, a prolific, stylish short-story writer in great command of her medium, dexterously revels in the humor and horror of coming of age whilst weary of the ways of the world. — Jordan Taliha McDonald

“As a creative, I’ve decided I’m going to do what I do best: I’m going to tell you a story,” Michaela Coel announced in her now-infamous 2018 MacTaggart Lecture at the Edinburgh TV Festival. What followed was a proclamation of purpose and placemaking that narrated her journey from a youth living in East London’s Tower Hamlets estates all the way to her successes in theater and TV, as the star and writer of Chewing Gum (which she has, of course, since followed up with the series I May Destroy You). Coel builds upon that speech in this new book, indulging in the celebration of creative expression without sacrificing a critique of the obstacles that she and other “misfits” face when trying to make art in hostile territory. Misfits, she articulates, are the marginalized and the misunderstood, those who seek neither profit nor protection from the mainstream. Addressing matters of sexual violence, racial discrimination, and structural inequality in corporate media, she anchors her words in the wisdom of the wayward, those who seek only the freedom to manifest a world in their own outcast image. — Jordan Taliha McDonald

Marlowe Granados’s debut novel, first released last year in Canada and now published by Verso, chronicles an especially social New York City summer. Everywhere are gossip girls, fuckboys, and party people, each “a friend of a friend of a friend.” Enmeshed in this rather chain-linked lifestyle is 21-year-old protagonist Isa Epley, a self-proclaimed expert at “coming and going.” Beside her, amid a slew of tagalongs, is her bestie, Gala Novak. The pair have no work visas, so they do odd, pseudo-glamorous gigs for cash and try to get their drinks paid for. Written in journal entries, from May through September of 2013, the narrator is sardonic and necessarily unreliable. The superficial lightness of Granados’s spare plot resists an undercurrent of darkness. Why else would Isa fill her every spare moment with the company of all these duds? — Tiana Reid

The medieval nun drama you didn’t know you needed. Groff turns back the clock to 12th-century Europe to reimagine the life story of an obscure historical figure named Marie de France. At 17 years old, Marie is cast out of the French royal court by Queen Eleanor, whom she adores, and sent to rural England to be the new prioress of a failing abbey where the nuns are sick and starving. Though at first horrified by her assignment, Marie soon finds a sense of purpose and spiritual fervor in the community of women. There is also more than a little sexual tension between the nuns, and the straightforward descriptions evoke the quiet electricity of bodies together in space. The femme energy in this book is strong, with hardly a man to be found in 272 pages, which I found salutary in a way I hadn’t expected. Fans of Groff’s earlier work, particularly Arcadia (2012), will appreciate her gift for conjuring isolated communities, places where people are forced together by faith and circumstance — and the intimacies and frustrations that result. — Cornelia Channing

“For some time, I thought a book on freedom might no longer be necessary — maybe not by me, maybe not by anyone,” writes Nelson in the introduction to On Freedom, the latest work of cultural criticism from the author of The Argonauts and The Art of Cruelty. “Can you think of a more depleted, imprecise, or weaponized word?” She approaches the knotty subject with characteristic candor, asking what it means to be free in the world today and how ideas of freedom shape conversations about literary form, art, sex, politics, and even climate change. As she has in previous books, Nelson draws upon a wide array of material, from critical theory to pop culture to exchanges with family and friends. Throughout, her sensitivity and emotional presence soften the hyperintellectual, almost academic quality of her writing. She leads with feeling, exploring what she calls “the joys and pains of our inescapable relation.” — Cornelia Channing

Through a winding email correspondence, best friends Alice and Eileen connect at a distance in this torrential meditation on life as it passes through our various feeds on our screens. Like Rooney’s previous novels, Beautiful World, Where Are You follows the lives of young Europeans navigating work, friendship, sex, and romance. All her trademarks are present: hostile loneliness, inexplicable depression, white guilt, self-assured education. All the characters perform a familiar dread, constantly analyzing and rethinking, opening and closing tabs, typing messages in apps and then deleting them. Some critics have dismissed Rooney’s work as a mishmash of Marxist-identified white women’s millennial literature, painting it as out-of-touch and self-important even if self-aware. But through her timidly marvelous sentences, Rooney shows how the severe individuality required by intellectual life is disturbed by the political difficulties of intimacy. — Tiana Reid

In this harrowing tale that echoes our current moment, a group of clothed people imprison a coterie of naked people in a squalid house. The protagonist, a member of the oppressed naked, narrates as the naked are subjected to a sequence of increasingly perverse degradations, including torture, sexual abuse, and murder. Eventually, the protagonist initiates a personal campaign of rebellion that draws him closer to the truth about the relationship between the oppressors and oppressed. Hauntingly translated from the Spanish by Victor Meadowcroft and Anne McLean, Rosero’s novel — originally published in 1992 — reads as a parable that is firmly grounded in our merciless reality. If any of this seems too intense or extreme, sit back, close your eyes, and imagine what it would be like to live in a society in which an exclusive club of billionaires ruthlessly exploits their employees and the planet. Now open your eyes. Surprise! — Tope Folarin

Few economists go viral as often as Adam Tooze does. When he writes, be it on China’s status as a superpower or the questionable influence of Paul Krugman, the internet listens. His writing demystifies the world before us, dispelling the cloud created by the chaotic motivations and invidious narcissism of the market. Shutdown: How Covid Shook the World’s Economy is one such cure, a book that answers so many questions about the state of the world that it will leave its readers feeling not just more learned but dizzy too. It is cliché at this point to remark that after COVID-19, everything changed; what Tooze illustrates masterfully in Shutdown is that the crisis the virus unleashed began much earlier, the world order’s fragility the product of a much longer process of mismanagement and selfishness. — Kevin Lozano

Start with the title story and don’t look back. Hao is a Mandarin word that means “good,” among other things, and words are Ye Chun’s superpower. A translator and poet, she uses them sparsely, delicately, aware that each one carries unseen weight. In this debut short-story collection, Ye’s stories spread across hundreds of years and the Chinese diaspora: “Hao,” set during the Cultural Revolution, charts the downfall of a mother after she unthinkingly uses a taboo word. In “Gold Mountain,” an immigrant caught up in the wild anti-Chinese race riots in 1877 San Francisco struggles to understand the words her tormentors shout. These stories are immaculate, beautiful, tattered — like their characters. — Hillary Kelly

In her latest, the translator and essayist Lauren Elkin compiles a series of reflections written in her phone’s Notes app as she commuted on a Parisian bus in 2014 and 2015. These scribbles run the gamut from droll to devastating: Elkin writes about lesson planning, an ectopic pregnancy that changes everything and nothing at the same time, and the aftereffects of the terrorist attack at the Bataclan. In her cogitations, the ordinariness of loss bristles up against time’s unyielding forward momentum. By cataloguing the vicissitudes of personal and social life — observed privately, but still within the context of public transportation — No. 91/92 redoubles the questions around intimacy and proximity that have always and will ever continue to plague us. — Omari Weekes

This gripping novel by the Australian writer of Big Little Lies and Nine Perfect Strangers follows the mysterious disappearance of Joy, an old woman in Sydney, who vanishes one Valentine’s Day after sending a confusing text to her grown children. As Moriarty reveals more about Joy’s life — her marital issues, her complex family history, and Savannah, the stranger who mysteriously showed up on Joy’s doorstep the night before she disappeared — she builds a sense of urgency and cements herself as a master of mystery, using every detail in her tangled narrative web to keep the reader guessing until the final shocking twist. — Mary Retta

Harlem Shuffle follows Ray, a furniture salesman and family man who descends from a long line of “crooks.” When Ray’s cousin Freddie volunteers him to assist with an illegal heist, Ray begins to have an identity crisis: Is he a crook or a salesman? Can he somehow be both and still maintain his family and reputation? True to form, Whitehead’s writing is snappy and forceful, moving the plot along at a pace that will keep the reader furiously turning the pages. New York plays a major role in the narrative, as Whitehead uses the backdrop of 1960s Harlem to pose complex questions about masculinity, race, and power. At once a crime novel and a family saga, Harlem Shuffle is a love letter to Harlem and the larger-than-life characters who inhabit it. — Mary Retta

In her first novel since 2000, Williams brings us a story that is as bizarre as it is riveting. Set in a dystopian American West, the novel follows Khristen, a teenager sent away to a boarding school that is shut down shortly after she arrives. Alone and aimless, Khristen sets off across a decimated desert landscape and eventually comes upon a cultish community of elderly ecoterrorists living in a hotel on the shores of a toxic lake. There, she befriends a number of batty “oldsters” and a 10-year-old boy named Jeffrey, and, together, the unlikely cast resists the tide of environmental ruination that threatens to destroy their world. The novel operates on a kind of dream logic that is dark and disorienting at times, but readers willing to embrace the eccentric will be richly rewarded with Williams’s funny, whip-smart storytelling. (This book would also pair well with Alexandra Kleeman’s recent novel Something New Under the Sun.) — Cornelia Channing

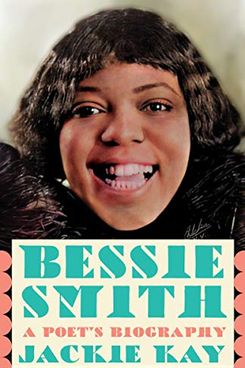

The Empress of the Blues was a woman of appetites — for women, for men, for parties, for food, for drink, for fighting, for gifts, for love. This reissue of Kay’s 1997 biography, which includes an elegant introduction by the author, reminds us that Smith is not just a lively personality, but a critical figure who defied conventional notions of what it meant to be a Black woman of working-class origins. It charts Smith’s turbulent rise to fame from her southern upbringing in Chattanooga, Tennessee, and mixes that with Kay’s own story of growing up Black in a small Glasgow suburb. No attempt at cold and rigid objectivity here: Kay is a lifelong fan and proud of their shared Black queerness. Adopted by a white family in the 1960s, Kay didn’t know anyone besides her brother who looked like her, so she made Smith her own: “My libidinous, raunchy, fearless blueswoman. I am still full of her passion.” — Tiana Reid

Grieving his father, teenage Benny has started hearing voices, the ongoing chatter of all the things in the world around him. In her latest novel, Ozeki (the only Zen priest ever shortlisted for a Booker Prize) relates Benny’s encounters — with a mysterious girl he meets in the psychiatric ward, a homeless poet, and his mother Annabelle, a woman overcome by her own mountains of stuff. While Annabelle seeks solace in a book about mindful tidying up, Benny finds the Book, both object and character, which Ozeki intends to be the very book the reader is holding. Sometimes the Book intervenes in the story as a gentle narrator, trying to sort through the confusion brought on by the Shakespearean cast of characters. As a reader, you might feel the pressure of yet other books pushing against the plot’s spine, too: memories of Ozeki’s earlier work, Borges, and Kafka. — Helen Shaw

Theo Byrne is a widowed astrobiologist searching for life on other planets and struggling to raise Robin, his neurodivergent 9-year-old son. Robin is a sensitive, inquisitive kid, who asks an enormous number of questions — about stars, about climate change, and about death — and spends hours painting. He can also be difficult, even hostile, and is at risk of being expelled from school. Theo has been advised to put Robin on psychoactive medication, but struggles with the decision and tries instead to channel Robin’s energy and curiosity into science and activism. Powers won the 2019 Pulitzer Prize for his novel The Overstory, a book which was remarkable in part because it foregrounded the lived experiences of trees. In some ways, Bewilderment looks even further afield — into the vast mysteries of outer space and the human mind — while offering a more introspective story. This novel asks big questions about what parents owe their children, the future of our planet, and how we rationalize its constant destruction. — Cornelia Channing

Translated from Norwegian by Martin Aitken

Knausgaard may be over Knausgaard — or is at least feeling ready to get back to the work of down-and-dirty fiction. The Morning Star, his first novel since the conclusion of My Struggle and the first book in what he says will be a new series, skirts the supernatural, or at least the outer limits of our understanding of the universe. It’s also more than a bit Biblical: In Southern Norway, a group of loosely connected people see a massive glowing star in the sky. Is it an unexpected astronomical event or a sign from the heavens? Knausgaard still hasn’t come around to brevity — The Morning Star is nearly 700 pages — but I’m eager to see what he can do when he’s untethered from “real” life, from his cigarettes and musings. If he lives up to his own reputation, I’ll send a flare up to the stratosphere myself. — Hillary Kelly

This dense and tightly plotted novel — the Nobel laureate’s first in almost 50 years — is also allusive, fantastically ambitious, and populated with a cast of outrageous characters who are attempting to thrive in an outrageous country. Among them are Dr. Kighare Menka, a surgeon who specializes in treating terror victims; Duyole Pitan-Payne, an engineer with a flair for the dramatic; and Prince Badetona, an accountant who has grown too comfortable with corruption. Soyinka sets them — and many others — on a path that sends them careening into and away from each other, against a backdrop that isn’t quite contemporary Nigeria. He makes no concessions for readers unfamiliar with the vagaries of Nigerian politics, and in so doing fashions an immersive reading experience that might be difficult for some to enter but proves even harder to escape. — Tope Folarin

October

This is fiction as an act of bearing witness — in this case, to the historical trauma of Haiti’s January 2010 earthquake, in which as many as 300,000 people were killed. A handful of interconnected lives orbit the tragedy: a water executive, a drug dealer, an NGO worker, a produce seller in the market. Chancy’s lush prose engages shifting and intersecting points of view that reflect the contours of an island nation borne of anti-colonial rebellion. Here, death and grief live alongside the beautiful and mundane, the haunting of American imperialism alongside Haiti’s resilient sovereignty. People watch telenovelas, scrape together a living doing domestic work, love and are loved in ways that wound and sustain. The condition of crisis that Chancy evokes, simultaneously unimaginable and everyday, resonates as loudly as ever. — Mik Awake

The first volume of what promises to be a sprawling new trilogy from Jonathan Franzen, Crossroads follows a family living in a fictional small midwestern town during the final years of the Vietnam War. Each character stands on a precipice, wobbling between feelings of temptation and failure, autonomy and dependence, righteousness and regret. Readers familiar with Franzen’s previous work — particularly Freedom and Purity — will notice that the author is mining similar territory here: strained ties, shifting political mythologies, and the comforts and anxieties of suburban America. But the scope of this novel feels somehow even more monumental. (The title of the trilogy is, after all, A Key to All Mythologies, a reference to Casaubon’s unfinished work in Middlemarch and a nod to Franzen’s expansive ambitions.) — Cornelia Channing

Women have had ample reason to paint self-portraits over the years, from the urge to leave their own indelible images on canvas to lack of other available subjects, as life classes were long closed to them. This wide-ranging group biography by the former editor of Frieze magazine covers artists such as Catharina van Hemessen, whose 1548 self-study at her easel is thought to be one the earliest by a man or woman; turn-of-the-20th-century trailblazers Gwen John and Paula Modersohn-Becker; and pop figures like the ever-relevant Frida Kahlo (who rejected the moniker “woman artist” entirely) and modern savant Alice Neel. Higgie has organized the book thematically (“Easel,” “Smile,” etc.) to bob and weave through the ties that have bound female painters — and blow open the so-called liberties they’ve taken with their art. Coming exactly 50 years after Linda Nochlin published her famous essay “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?”, Higgie wants to lay the question to rest, once and for all. — Hillary Kelly

While other music critics bicker over banalities (an album’s quality as defined by a rating out of 10, for example), Kelefa Sanneh has been setting the terms of debate for over a decade. If you have ever been cajoled into a conversation around poptimism, rockism, or authenticity in music, you can probably blame Sanneh for opening that Pandora’s box. His range has widened since joining The New Yorker as a staff writer — he now writes on politics, philosophy, economy, coffee, and whole lot more — and that capaciousness is a defining characteristic of his debut book, Major Labels: A History of Popular Music. In it he explores 50 years of music history to answer a seemingly impossible question: What the hell is a genre, anyway? Is it a form of cultural identification? An industry-created designation? A critical exercise? All of the above? An essential document from an inimitable critic. — Kevin Lozano

This autobiographical-ish novel by our most significant rising writer of the American West is a wild ride. Watkins’s first two books — the remarkable short-story collection Battleborn and California cli-fi epic Gold Fame Citrus — presented her as the 21st century’s Steinbeck, a novelist so baked by the desert sun that sand practically spilled out of her pages. Now she’s taken that reputation, torn it to shreds, and reassembled it into this blazing, genre-crossing collage. I Love You But I’ve Chosen Darkness is a road trip story gone wild peppered with letters her mother wrote as a teenager in the 1960s, her father’s account of his time as Charles Manson’s right-hand man, and “Claire’s” (?) own story of months spent running away from her life as a mother, writer, and teacher. It’s career-redefining and absolutely bonkers in all the best ways. — Hillary Kelly

Translated from Portuguese by Margaret Jull Costa

Considered by many to be among the greatest Portuguese writers of the 20th century, Maria Judite de Carvalho’s work has rarely been translated into English. So the publication of this 1966 novel by the literary-translation house Two Lines Press is an occasion for both celebration and sadness — celebration because this is fine, engrossing work, and sadness because why the hell did it take so long? Featuring an introduction by Kate Zambreno, Empty Wardrobes foregrounds an idea that seems to haunt many modern stories: that our lives can unspool according to false narratives that have no connection to reality. A widow spends a decade mourning the death of her husband until she learns an unnerving secret that prompts her to reevaluate her marriage. Thus begins a fraught journey, rendered in cool, gleaming prose, during which she attempts to develop a new personal story that might one day help her surmount her circumstances. — Tope Folarin

The poet widely known as Lucille Clifton arrived on the planet with a different name: Thelma Lucille Sayles. This book, first published in 1976 and billed as a memoir, is mostly a collection of anecdotes about the Sayleses, her father’s side of the family. Clifton crafts an exquisite net of language and casts it into her family’s past to capture the stories of Caroline (known in the family as “Ca’line”), a woman with an “Oxford accent” who was stolen from Africa as a child; Lucy, Caroline’s daughter, a woman who “didn’t do nothing she didn’t want to”; Gene, Clifton’s grandfather, a handsome man with a withered arm and skin the color of cinnamon; her father Samuel, a keen reader who “could barely write more than his name,” and her mother Thelma, “a round brown lady” from Rome, Georgia. Clifton, who died in 2010, introduces each section with a black-and-white photograph of the relevant family member, daubing these images with the kind of animating details that grant them life — both on the page and within us, her lucky readers. — Tope Folarin

Set in Mombasa, a historic East African trading post and Kenya’s second largest city, this is the contemporary fable of a young girl’s adventure on sea and land. After her fisherman father goes missing on the Indian Ocean, Aisha sets sail in a boat made of bones to find him, accompanied by a talking feline — but even more reality-warping are the confines of patriarchy she confronts upon her return. Bajaber’s writing is matter-of-fact and gem-cut; her debut will likely be an introduction for many readers to the culture and lore of the Hadrami diaspora, a people with roots in what is now Yemen and centuries of seafaring history spread across the rim of the Arabian Sea. Selected by acclaimed Nigerian novelist A. Igoni Barrett to receive Graywolf’s inaugural Africa Prize, this debut carries the invigorating mystery of the sea, its unpredictable leap and roil. — Mik Awake

The Days of Afrekete tells the stories of Liselle and Selena, two Black women who dated briefly during college, struggling with the cumbersome aspects of being middle-aged. With so much history behind and between them, they live their days apart, holding on to a longing for the other that often escapes legibility. Solomon echoes the deep feminine bonds at the center of novels like Nella Larsen’s Passing and Toni Morrison’s Sula to reveal how the erotics of our past lives shape our futures even when we think the desire is long gone. As Liselle navigates a dinner party for her husband, who has just lost a congressional primary and may be indicted for corruption, the intimacy between these former lovers and current strangers recurs and unfurls anew. — Omari Weekes

A peripatetic, multigenerational saga, Monster in the Middle is a meditation on love, especially the Black love of Fly and Stela across the landscape of late 20th- and early 21st-century America. The book is a departure for Yanique: Her previous two, a story collection and novel, centrally concerned the U.S. Virgin Islands, where she is from, and leaned toward the historical and magical. A professor of creative writing at Emory University, Yanique is a writer’s writer, one of the most inventive and talented stylists of her generation; excerpts of this project have appeared in The New Yorker and Best American Short Stories. With this much more contemporary novel-in-stories, Yanique explores the way love can echo along the corridors of history, through police brutality and a pandemic, deftly weaving and juxtaposing the trajectories that make love possible. — Mik Awake

“The part of life/devoted to contemplation/was at odds with the part/committed to action.” I’ve been rolling over this aphoristic stanza in Louise Glück’s new collection Winter Recipes From the Collective in my mind for weeks now, because it seems to speak to the riddle of our strange days with startlingly directness. Glück mines the variegated beats of human existence for something shared and intimate, or as the Nobel committee said when she was awarded the Prize in Literature last year, she bears an “unmistakable poetic voice that with austere beauty makes individual existence universal.” This slim volume (15 poems in all) distills all these qualities, beckoning the reader to enter in conversation with one of the great poets of our times. — Kevin Lozano

At the center of Black Paper is a series of lectures that Cole delivered at the University of Chicago in 2019 about the senses — how they operate, how they mediate our relationships with one another and our environment — yet the book travels much farther afield. Cole, himself a writer and photographer, offers elegies to thinkers and artists such as Nigerian curator Okwui Enwezor, Swedish poet Tomas Tranströmer, and Aretha Franklin; he also appraises the career of Caravaggio while describing the difficulties faced by refugees in Europe. What links these topics, and so many more, is the wisdom of Cole’s sentences, each of which could be plucked from its context and endure on an empty page. Read this book and observe the realized potential of a finely tuned mind: an ability to forge a living body from disparate parts. — Tope Folarin

When Melissa, a young Latinx poet who has grown listless, turns to the art of necromancy, she chooses to bring none other than the inimitable Selena Quintanilla-Pérez back from the dead. (The Tejano pop star’s posthumous fifth and final album is also titled Dreaming of You.) Through verse poetry, the novel delivers a contemplation of veneration and self-invention, practices that produce both catharsis and casualty. With the intensity and fluidity of a fever dream, Lozada-Oliva situates the figure of the assassinated superstar — “a star I can only see because it has died” — alongside the protagonist Melissa’s own self-narration. By reckoning with the complexities of celebrity, self-identity, citizenship, social media, and sisterhood, Lozada-Olivia names what it means to be both endangered and enraptured by hypervisibility; it is an invitation to “make your own light,” to recast shadows. — Jordan Taliha McDonald

November

Merchant-Ivory is best-known for lush, slow-burning novel adaptations, full of subtleties in the lightest of touches and lingering glances. At 93 years old, writer and director James Ivory is the last living member of the filmmaking triad — which included his longtime romantic partner and producer Ismail Merchant and screenwriter Ruth Prawer Jhabvala. His memoir ponders the foundations of their simmering cinematic language: There’s 5-year-old Ivory’s first visit to a movie theater in Klamath Falls, Oregon; his time at the University of Southern California’s film school; the making of Merchant-Ivory’s first E.M. Forster adaptation, the breakthrough success that was A Room With a View, and so much more. He pulls focus through his memories pretty candidly: Before a series of tender portraits that include Merchant and peers like Susan Sontag and Jhabvala, Ivory details the ups and downs of writing and producing. But undergirding it all is Ivory’s passion, for history, beauty, and love, a fondness in almost every recollection. — Rina Nkulu

Translated from Spanish by Adrian Nathan West

In 1954, fueled by fears about the alleged spread of communism, the CIA orchestrated a coup in Guatemala. The latest novel by Llosa, a wildly prolific Nobel laureate, focuses on a number of figures surrounding the ousting of then-president Jacobo Árbenz. Some are real, like Carlos Castillo Armas, who immediately took power after Árbenz was deposed, and some, like Martita “Miss Guatemala” Parra, Armas’s mistress and adviser, are imagined. Llosa begins the story with the birth of the United Fruit Company’s lobbying efforts — its paranoid fictions of Guatemala as a “Soviet Trojan horse” soon to seize the Panama Canal — and stretches past Armas’s own assassination, in 1957. After is where the perspective shifts, and though we come away with more questions than answers, we can be absolutely certain of the tragedy incurred. — Rina Nkulu

Shteyngart’s new novel begins in the early days of a global pandemic, as a group of acquaintances decamps to a country house to wait out the virus. Over the ensuing six months, friendships and romances are formed and old betrayals rear their ugly heads, forcing the characters to reevaluate the directions of their lives. (Any of this sound familiar?) The housemates include a Russian novelist, his psychiatrist wife, their K-pop-obsessed child, a struggling Indian American writer, a super-successful Korean American app developer, a global traveler with three passports, a Southern essayist, and, to top it all off, a movie star. Shteyngart knows how to make you belly laugh, and he’s in his element here, poking fun at the claustrophobia of privilege. He perfectly captures the nature of adult friendships and the petty jealousies, disappointments, and dependencies that can define them. — Cornelia Channing

In Erdrich’s latest, an independent bookstore in Minneapolis becomes the site of a yearlong haunting. In 2019, just before the onset of the pandemic, Birchbark Books, which specializes in Native literature (and happens to share a name with Erdrich’s own real-life bookstore in the Twin Cities), is visited by the ghost of Flora, a white woman with a tricky past. Obsessed with Native American history, Flora fabricated Indigenous roots for herself, concocting a vivid identity delusion that continues to reverberate after her death. As the COVID-19 pandemic takes hold and Birchbark pivots to mail orders, several members of the staff join the protests against police brutality and battle ghosts both personal and ancestral. Erdrich toys with genre constraints: This is a ghost story, yes, but it is concerned more with the dark phantoms of reality — the shadow of a devastating pandemic and the generational damage of systemic racism — than the thrill of the paranormal. — Cornelia Channing

The anthropologist David Graeber was a pathbreaking theorist, a committed activist, and an ally to the marginal and the downtrodden — a public intellectual in every sense. Perhaps best-known for his 2011 book Debt, he dedicated his life and work to understanding how the machinery of daily life became so oppressive to vast swaths of the planet’s populace. He died last year at age 59, weeks after completing his final book project, this collaboration with David Wengrow. In the book’s foreword, Wengrow describes it as “an experiment … in which an anthropologist and an archaeologist tried to reconstruct the sort of grand dialogue about human history.” Indeed, this massive text takes readers back 200,000 years to upend the conventional understanding we have of our ancestors, giving radical readings on everything from the origins of farming to the meaning of civilization. The goal is to show how in the doldrums of what we call history, we might be able to chart a course to a more liberated future. — Kevin Lozano

Anwuli Okwudili, the protagonist in this novel by a veteran Afrofuturist author, prefers to be called AO: Artificial Organism. AO has never felt natural, especially after surviving a horrific car accident that disfigures her body so badly that people in her village think it was the work of the devil. One day, after a shocking and violent encounter at the market, AO is suddenly forced to flee her village and hide. Similar to Okorafor’s work in her renowned Binti series, Noor follows a young woman on a fated journey. The brilliant first-person narration puts the reader inside AO’s mind, allowing an intimate view of the protagonist’s fear, confusion, and bravery. The fast-paced narration and honest, curious characters construct a world where technology is natural, bodies are arbitrary, and time is a thing we make up as we go. — Mary Retta

It takes an expert to play with the short-story form like this. Wideman is known for chaotically blurring the lines between historical event and personal memory in novels like 1990’s Philadelphia Fire. Here, Wideman showcases how narrative disorders time and space, revealing the yawning distance between what we think we know and what actually exists. These stories slide from fiction (“Lost Love Letters — A Locke” narrativizes the life and death of Harlem Renaissance mainstay Alain Locke through letters, lectures, and excerpts from a memoir in progress) to nonfiction (“George Floyd Story,” a staggering meditation on the time of mourning) and back again. These are part and parcel with the tradition of postmodern Black storytelling — part fiction, part lived experience, all truth — and Wideman continues to excel within it. — Omari Weekes

In an essay published in Harper’s in January, Patchett writes, “How other people live is pretty much all I think about. Curiosity is the rock upon which fiction is built.” This voracious curiosity is a defining characteristic of her fiction, evident in novels like Bel Canto and State of Wonder, which hum with well-researched specificity. Curiosity is a guiding principle once again in These Precious Days, this time in service of nonfiction. In these essays, Patchett mines her own experiences, thoughts, and relationships, teasing deep and unexpected meaning out of the stuff of everyday life. The emotional center of the book is the title essay, which tells the story of Patchett’s unexpectedly close friendship with a woman named Sooki, who was Tom Hanks’s assistant (long story) and with whom Patchett shared a singular bond. In Patchett’s hands, each subject becomes a springboard for thoughtful digression. — Cornelia Channing