Kobe Bryant blew up my phone once. He didn’t have my number, although he was known to cold-call writers like that. He’d text basketball players, too, with the same one-liners for superstars and teens alike. But in this particular case, my iPhone actually malfunctioned, the result of a real-estate broker in San Antonio responding to my tweet about a story we ran at Bleacher Report’s magazine in 2018, which prompted Kobe to go at the guy. Good-bye, my mentions; hello, Genius Bar.

In my two-year journey off the court with NBA players, no presence proved more influential than Kobe. More than Michael Jordan. (Except maybe the sneakers.) More than LeBron. (Except for his politics.) He was a mentor to the Brooklyn Nets’ snake charmer Kyrie Irving, who would call the so-called Black Mamba on the verge of championships, fatherhood, movie deals, anything, anytime. “I saw what he was creating,” Kyrie explained to me, “and I knew that I wanted the same structure: He had his own company, he had his own belief system, he had his own principles that he lived by. He didn’t give a fuck what anyone said.”

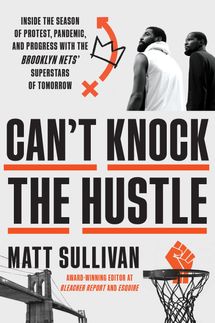

I left an email to the Black Mamba in my Drafts folder on Sunday, January 26, 2020 — the kind you wait until Monday to send in hopes of a quicker response. What happened that morning, and that year, was sudden, and scary, and sad. But Kobe’s legacy will be in the joy of its everywhere effect. And he swooshes all throughout my book, Can’t Knock the Hustle: Inside the Season of Protest, Pandemic, and Progress with the Brooklyn Nets’ Superstars of Tomorrow. It opens with Kyrie aboard Kobe’s helicopter, seeking career advice — on the condition that the student guest-coach for the professor’s team, which starred 13-year-old Gigi Bryant. It ends at Kobe’s gym in California, where I’d gotten a look inside the room for an all-star seminar and where, on Election Day, a secret pickup game between Kyrie, Kevin Durant, and James Harden helped a dynasty grow in Brooklyn.

The final public appearance described below, before the crash, is how we’ll remember The Mamba and the girl-dad all the same: underground with no-name Nets and teenagers from Kyrie’s high school, courtside with Brooklyn’s almost-all-star Spencer Dinwiddie, and in a loving moment shared across our feeds. RIP, Kobe and Gigi.

Excerpt From 'Can’t Knock the Hustle'

Kobe hated going to NBA games. Too much attention. Too many people. Too many selfies. “To make the trip,” he said, “that means I’m missing an opportunity to spend another night with my kids, when I know how fast it goes.” He was 41, and he’d hardly watched pro basketball in the two and a half seasons since he’d retired — until Gigi, the second oldest of his four daughters, became a legitimate pro prospect herself, at 13 years old. Now they were watching NBA League Pass together every night. Those Batphone text messages to rookies, the pro camp back at The Sports Academy in August, all that elder shit — Kobe didn’t necessarily do all that, except when he was doing it for his guys Kyrie Irving and Kawhi Leonard and maybe Russ Westbrook, because he wanted to. He did that because the legends who’d come before him had passed down heirlooms for safekeeping: the blue-chip investments, the public deference of the talented, the all-timer’s tricks of dirty play. That was a call of duty. But this, with Gigi, this was love and basketball. This was seeing sport through her eyes.

So they went to a game at Staples Center before Thanksgiving — Kobe’s first time back since they retired both of his jerseys, 8 and 24, a couple seasons earlier — because the Lakers were playing the Hawks, and Gigi loved Atlanta’s deep-range shooter Trae Young, the way he could chuck threes with the flair of Steph Curry, at 21 years old. She and Trae even shared their trainer with Kyrie. And tonight, the Nets were playing Atlanta, in Brooklyn. C’mon, Dad!

“All right, fuck it,” Kobe told the trainer. “Let’s just go to another fucking NBA game. Gigi wants to go.”

He talked his wife out of some extra Christmas plans in the city and watched Gigi hoop at the office of the players’ union in Midtown with another top girls’ basketball phenom. By late afternoon, Kobe and Gigi were working out again, in the private underground practice gym at Barclays Center. On their way upstairs to the game, the Bryants greeted some of the Nets’ developmental projects heading in for extra work. The players marveled at, though were not in the least shocked by, Kobe grinding through drills in a pinstripe designer tracksuit and low-tops.

Fifteen minutes before tip-off, Spencer Dinwiddie spotted Kobe courtside. They’d talked and texted a few times, but hadn’t been able to schedule a workout together. All of a sudden, Spencer thought, this was The Mamba in person, man! Finally! Spencer had a damn poster of Kobe on his wall growing up, and to that day he had an autographed No. 24 jersey in his room.

“You’re playing like an All-Star,” Kobe told him. “Keep it up.”

“Shit, man, I’m tryin’,” Spencer said.

“Nah, you ain’t tryin’ it. You doin’ it.”

Kobe and Gigi settled down next to Clara Wu Tsai and her son in the owners’ seats next to the Brooklyn bench. Kenny Atkinson was coaching so hard that he didn’t notice Kobe directly behind him. Spencer noticed: He was never shook by opposing fans or by guarding LeBron, but Kobe’s presence made Spencer, not two minutes into the first quarter, straight-up clank a twenty-five-footer off the backboard.

The Barclays Center crowd had been pretty dead that Saturday evening, until they put The Mamba on the big screen. Kyrie geeked out, stretching his achy shoulder out of his corduroy blazer and craning his neck for a look at highlights from what became known as the “Mamba Out” game, when Kobe dropped sixty on Utah in his career finale. The Barclays cameraman stepped closer toward Seats No. 7 and 8, and the scoreboard operator beamed Kobe and his daughter up into the Jumbotron. Kobe offered the tacit selfie grin of a purist who’d rather be in an empty gym, but Gigi smiled, her cheeks so wide they made her eyes close. The crowd smiled a little wider, too.

There was another burst of cheer in the second quarter, when Kobe stood up to greet Vince Carter. At 42, his contemporary — no longer living the dunktacular legend of Vinsanity from his heyday on the Nets and Raptors — was on a final season’s lap around the league with the Hawks, and the OGs locked fists.

“How you holdin’ up in retirement?” Vince laughed.

“I’m happier than I’ve ever been, man,” Kobe said. “Happier than ever.”

In the third quarter, with the Nets down thirteen to the worst team in the conference, Atkinson got called for a technical foul. He and Kobe, who was rooting for the Nets, had been shocked by the referees all game long. Expletives had been used. But during this break in the action, a camera scanning courtside spotted Kobe, pleasantly inhabited by an almost unfamous happiness, teaching his daughter about the game. Kobe loved the rhythmic nature of this sport, how sometimes you could hear the ball before you saw it. After he tore his Achilles tendon in 2013, he would listen to Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony and marvel at how the maestro had composed it while legally deaf — and then, because he was Kobe Bryant, he learned how to play the piano by ear. Watching the silent cutaway at Barclays, as the girl-dad leaned in and conducted his hands toward the court, nobody could quite tell what Kobe was explaining to Gigi. The clip was only nine seconds long, but pretending to read this maestro’s lips became the rare unmean internet meme, a blank caption in which any fan could imagine the lesson of their dreams. Within two weeks, the father-daughter moment would be watched more than 68 million times from one tweet alone.

But Kobe wasn’t thinking about his virality. At the final buzzer, he stood up onto the court, in his blue beanie and scarf, and bear-hugged Trae Young, who reminded Kobe what a fan he was — what a fan he was of his daughter — then dapped-up Vince Carter again, too. “Let’s talk more before end of season,” Kobe offered the OG, “but let’s continue to teach our daughters. We’ll talk more.”

In the postgame courtside congregation, Kyrie waited his turn; he’d had plenty of time with the professor. Besides, Kobe wanted to speak with Kyrie and Spencer, together. Spencer was sweaty — he’d relaxed enough in front of his idol to score thirty-nine points and keep the Nets in playoff position, after dropping forty-one the game before that — and he was satisfied.

“Man, you know why you didn’t get forty?” Kobe asked. “ ’Cuz you were thinkin’ about forty. You gotta go out there and think about sixty. And then you just fall right into fifty. ’Cuz you coulda easily had fifty tonight.”

The three of them shared a good, strong laugh, and Spencer hugged the poster on his wall. “You’re an All-Star in my book,” Kobe reiterated. Kyrie said he would catch Kobe later and pranced back to the locker room with his arm around his teammate. “There we go,” Spencer said, smiling at him as he turned back for one last glance at the legend. “There! We! Go!”

Kobe and Gigi were ready to pull out of the VIP garage at Barclays Center when a New Jersey boys’ high-school basketball team shouted: “Yo! It’s St. Pat’s!” Kobe stepped out of the Suburban and turned back around. He knew Kyrie’s alma mater. He used to play against them in his Philly days and talk trash in Italian.

Kyrie had helped to reopen St. Pat’s — as The Patrick School — and taken one player in particular under his wing. But Kobe immediately recognized the junior forward Jonathan Kuminga as one of the top prospects in the nation. Jon, who’d moved from the Democratic Republic of Congo to West Virginia at 13, to Long Island and The Patrick School in Jersey over the past year, knew he was good, but Kyrie had taught him to stay humble.

Kobe and Jon shook hands and stood in the middle of a team photo, inside of which two selfies were being taken. Kobe, of course, was more interested in a matchup that the Patrick School boys were hyping: their rivalry game against Roselle Catholic, which was going down here at Barclays — at Kyrie’s own tournament — in less than forty-eight hours.

“What’s your game plan?” Kobe asked the team.

All the kids answered all over one another.

“Feel good about it?”

“Yeah!”

“Then go out and do it.”

Kobe’s car drove out of the garage, the boys loaded onto their bus, and Kyrie emerged from the locker room toward his bulletproof Escalade. He had not expected to see his guests, happy to pay their way and receive no thanks whatsoever.

“Y’all good?” Kyrie asked the boys.

“Uh, yeah, we met Kobe!”

He had missed his mentor by seconds — one limo-size elevator door had closed as another was opening — but Kyrie was more interested in the game plan, too.

“You guys are good? Cool. OK, now what we doing against Roselle?”

After midnight, Jon Kuminga direct-messaged Kobe on Instagram.

Appreciate it today for the pic big bro it means a lot to me and my teammates

Kobe wrote back: My man!! Go get em!!!

Excerpted from the book CAN’T KNOCK THE HUSTLE: Inside the Season of Protest, Pandemic, and Progress with the Brooklyn Nets’ Superstars of Tomorrow by Matt Sullivan. Copyright © 2021 by Matt Sullivan. From Dey Street Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission.

Things you buy through our links may earn us a commission.