Brian Donnelly, a.k.a. KAWS, is one of the most famous artists alive. He seems to be everywhere, all the time. He’s worked with Christian Dior, Supreme, Swizz Beatz, Pharrell Williams, Nike, and Comme des Garçons. His work is colorful, super-smooth, expensive, but also available as mass-produced objects and gewgaws. He makes cartoonlike characters with X’s for eyes. I’ve been ambivalent about his art, other than having typical art-world envy of his success. Many see him as the crass end point of a commercialized system in which art has become more of an investment vehicle than a repository of actual cultural value.

He’s also a collector and a connoisseur of art by outsiders, visionaries, underdogs, cartoonists, graffitists, and other marginalized figures — artists who, in other words, are mostly kept out of art history. An exhibition of his private collection, “The Way I See It: Selections From the KAWS Collection,” at the Drawing Center is so exceptional that I now see his own art quite differently, as part of a much broader project inseparable from the whole.

The Drawing Center is packed to the rafters with 400 works by 60 different artists — all wildly different, and evidence that for every artist there is a specific style that might be pushed to its beautiful fulfillment. Everything here is figurative and on paper, which levels the playing field and connects the artists to each other. The show is also a pointed critique of collectors and institutions that shun drawing and outsider artists as minor.

“The Way I See It” features some of the greatest graphic artists of the 20th century, including Martín Ramírez, Jim Nutt, H.C. Westermann, R. Crumb, Yuichiro Ukai, and Susan Te Kahurangi King. On one wall is Hilma af Klint’s small 1934 watercolor of a genderless body supine beneath a boiling landscape, laying down a marker of excellence for this show. Martín Ramírez’s large Caballero features a magnificent desperado pointing his gun as his almost-hieroglyphic horse rears its head — a brilliant universal altarpiece.

A high point was a wall of coral-colored pencil drawings by Nicole Appel; next to her Homage to Roz Chast was Homage to Jerry Saltz. And don’t miss the entire wall of work by Helen Rae, who didn’t start working until she was in her 50s and had her first one-person show in 2015, at the age of 77. Her wild illustrations look like fashion pages implanted with sticks of colorful Pop-Cubist dynamite.

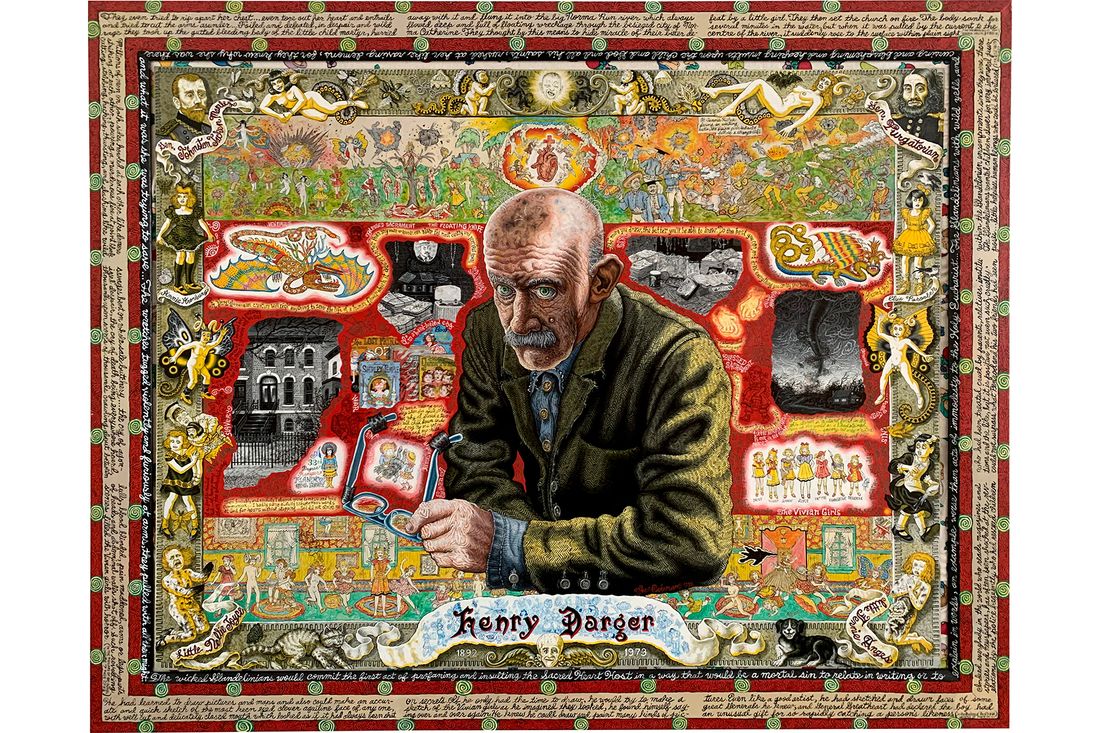

Big standouts are the graffiti artists, including Lee Quiñones, DONDI, DAZE, and CRASH, whose tremendous works adorned the sides of buildings and subway cars. Also, the insanely intricate portraits by Henry Darger and Adolf Wölfli should be in a museum. Not to mention the early drawings of Judith Linhares, Aurel Schmidt, and the great Joe Coleman, whose detailed works leave me speechless.

KAWS gets us to understand that, though 95 percent of art may be generic or derivative, there are always artists who jump the tracks of style and change it. He himself was long shunned by the art world before his work started to sell, and his show suggests that maybe the traditional gatekeepers are not always the best arbiters of what is good and what’s not. In 1990, another insider-outsider artist, Jim Shaw, mounted a massive show titled “Thrift Store Paintings,” featuring scores of pieces that Shaw amassed at swap meets, secondhand shops, and the like. Shaw’s squirrelly show changed everything by opening a hundred possible doors for thousands of artists. “The Way I See It” may do that for drawing.