This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

When Daniel Dumile’s wife, Jasmine, announced to the world on December 31, 2020, that her husband, the enigmatic, famously masked rapper MF DOOM, had died, shock cut equally through his fans and peers. His widow broke the news on her husband’s Instagram, revealing that the 49-year-old had actually passed two months before, on Halloween. Her message did not disclose a cause of death or explanation for the belated news but instead expressed personal love and gratitude for both DOOM and their late son, King Malachi Ezekiel Dumile, who died in 2017 at 14 years old.

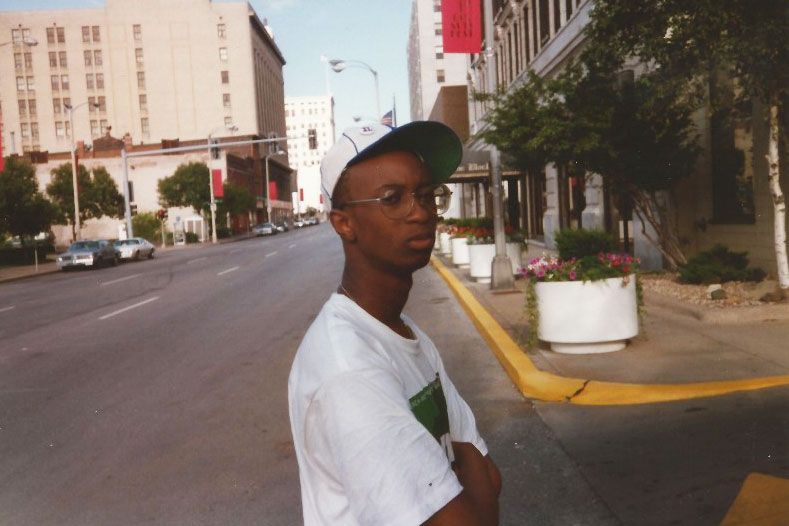

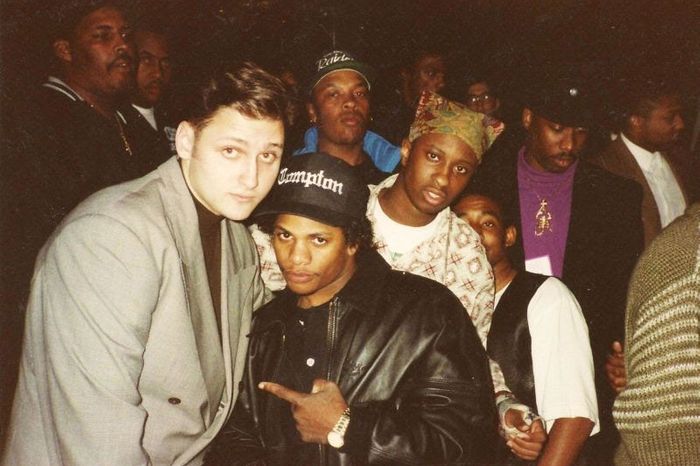

Daniel Dumile was born in London in 1971. He moved to the United States as a child and began his journey in music on Long Island during the late ’80s under the name Zev Love X, starting a hip-hop trio called KMD that also featured his younger brother, Dingilizwe Dumile, as DJ Subroc. Their collaboration was upended by tragedy: In 1993, Subroc was struck by a car on a local expressway and pronounced dead hours later. Elektra Records dropped KMD and shelved the group’s next album, Black Bastards; Zev Love X retreated from music. When Dumile finally crept back into hip-hop in the late ’90s, Zev Love X was gone and replaced with a masked supervillain persona called MF DOOM, inspired by Marvel antagonist Doctor Doom. From that point on, Dumile was rarely ever photographed without some version of his mask, replicas of the ones worn in the 2000 film Gladiator.

He went on to release six solo studio albums, six collaborative albums, and a slew of instrumentals, live albums, compilations, singles, and music videos. An anti-hero of underground hip-hop, he stumbled into crossover success when both his 2004 joint album Madvillainy with Oxnard producer Madlib and songs for Cartoon Network’s Adult Swim caught the attention of a new class of rap and cartoon fandoms at a time when those worlds were further intersecting online. In 2010, however, Dumile’s life was uprooted when he was denied reentry into the United States following an international tour; he had never become a naturalized citizen. DOOM was forced to spend his final years in the U.K., only adding to his mystique. Although he continued to work with other artists, his last solo album was 2009’s Born Like This.

DOOM built his legacy faceless and from a distance, to the extent that while all who had access to him can speak ad infinitum to his talent and humility, very few claim to have known the man behind the mask. Over the weeks following the news of his death, Vulture reached out to several of his collaborators, friends, associates, and admirers to get a fuller picture; below, they each tell stories of the Dumile they knew through the eyes of DOOM.

An Adolescent Prodigy

Pete Nice (3rd Bass, and the manager for KMD and DOOM from 1989 through 1995): When you look at DOOM and his progression as an artist, you have to look at those early days where you could basically say we put him on. We just had a single out that had a lot of success, and next thing you know, we embraced DOOM and his brother, and they were down with the crew. We put them in the video for our [1989] song “Steppin’ to the A.M.” and that was DOOM’s first appearance anywhere before he rhymed on our next single, “The Gas Face.” It thrust DOOM into a situation where we’re opening for De La Soul, and DOOM is opening for us. We’re asked to go on Yo! MTV Raps on a fishing trip with Run-D.M.C. and Fab 5 Freddy, and DOOM was right there next to us. We’re going on Arsenio Hall and DOOM is right there performing his verse. The topper was doing MTV Spring Break in Daytona where DOOM was with us and Biz Markie and Digital Underground, along with Ed Lover and Dr. Dre and Fab 5 Freddy.

I’m happy that we were able to facilitate that platform for him to really develop as an artist. He definitely did not sleep on that opportunity. DOOM was pretty much an adolescent prodigy who was so way ahead of his time in terms of the way that he would spit lyrics, the way he would write his lyrics with the metaphors, the double entendres. He grew up in a whole environment of cartoons and pop culture. And he would always throw in these slick little lines, referencing things that you might never think would show up in a rhyme.

Peanut Butter Wolf (Stones Throw Records founder, a.k.a. Christopher Manak): When I think of “shy,” I think of nervous and awkward and not a people person, but with DOOM, it was more like he was friendly and comfortable around people, but wasn’t really looking for attention or approval. Even though he was a year younger than me and I was the “label guy” and he was the artist, I looked at him as my elder because he had already been in the music industry before me, making records since 1989 when he was a teenager. He reminded me of my great-aunt who was a retired nun who taught prisoners how to meditate until she was in her 90s — really bright and also compassionate, not really opinionated or negative or complaining or gossiping. Just a positive and reasonable dude.

Phonte (collaborator): He was an emcee’s emcee, somebody who put words together and would just, I mean … absurd is the word that comes to mind. And I mean that in the most beautiful and humane way. It was like listening to somebody who rapped and knowing that they were doing it purely for the love of the craft. [At the time], I knew of KMD and I remember “Peachfuzz” and the whole Black Bastards controversy and all of that. When [KMD’s 1991 debut album] Mr. Hood came out I was like, shit, 12 years old. I was into hip-hop, but I wasn’t, you know?

Nice: I can remember the day that Subroc died. DOOM had been picked up on an old warrant for, I think, having an open can of beer or something, and the cops grabbed him and he was locked up overnight. So when Subroc was struck by the car in the afternoon, he was taken to the hospital and he didn’t pass until three or four o’clock in the morning. DOOM got out of jail and called his mother, and she had to break the news to him. I remember the call that DOOM made to me to tell me that Subroc had passed. He was in disbelief; it was like shock.

It’s almost a blur, that whole period where we had to plan the funeral, and his wake out on Long Island. We had Subroc in the casket and DOOM brought a boom box to play the Black Bastards album, which he felt was their masterpiece, that he and his brother had worked so hard on together. Subroc had finished most of his work and most of the vocals on it, and it was the most surreal experience. It was one of the toughest days of my life because I had to give acknowledgments and speak right next to the casket and right next to that boom box playing the album. It was something that DOOM knew that Subroc would want.

‘Do you understand the majestic gift that is Operation: Doomsday?’

Open Mike Eagle: There was an interview with him in Ego Trip magazine, and that’s when I first saw him with the old mask. He was wearing a big winter coat, and I started to get a little bit of his story: Oh, this was Zev Love X, and the guy on that 3rd Base song with Prince Paul. He was in KMD, and there was this whole thing with his brother that made him go underground. Now he’s reemerged as this new character who sounded like nobody I had ever heard before.

Questlove: It was the Voodoo record-release party for D’Angelo [in 2000], and Mos Def showed up in his kitted-up, chauffeur-driven van with music blasting. He rolled down the window and said to me, “Yo, you gotta get in here.” I tried to convey to him that Mark Ronson and I were DJ-ing the party, but he was like, “No, man. We gotta have a discussion.” I was preparing myself for some kind of deep talk, but he just started preaching the gospel of DOOM. I’m talking a 40-minute monologue, almost something like a Jehovah’s Witness would preach, trying to convert me to a new religion. He was like, “Do you understand the majestic gift that is Operation: Doomsday?” At the time, I had been listening to it with a different set of ears. [I said] “Oh, is that Zev Love X’s project?”

Before Mos turned me around, my early thoughts of Operation: Doomsday, and skimming through it, were, It’s post Wu-Tang; the loops are sloppy. Anita Baker and J.J. Fad? C’mon now … I can’t spin this in the club. My initial response was more scoff than whoa. Mos was not going to give up. He memorized that whole album like his life depended on it. He memorized it like my life depended on it. He made me listen to “Rhymes like Dimes” three times over. He was determined to convince me that it was the dopest shit out. He kept breaking it down to me until he finally planted the seed in me.

Open Mike Eagle: The first time I heard DOOM was on the University of Chicago college radio station WHPK, on a midnight hip-hop show [that] I’d tape and listen to in the morning. This was my feed into the underground hip-hop that was my lifeblood at the time. I got to the very end of one tape on my train ride to school, and it was a song called “Dead Bent.” I didn’t know who it was, or even the song title, until months later because the tape stopped before I could hear the DJ say who it was. It was this guy rhyming over an Isaac Hayes sample with drums that sounded like someone throwing rocks against a chalkboard. Man, it was crazy. It was immediately striking to me because it sounded like the style that I and the people in my community were doing when we got together to cypher and impress each other with punch lines; we’d bring the flyest rhymes we had, and make it seem like we were improvising them on the spot. It resonated with me so much, and I kept rewinding that part of the tape. The same thing happened a few weeks later with “Operation: Greenbacks.” That was the beginning of my love for MF DOOM.

Questlove: I did my homework during the next six months and realized that the new persona was DOOM’s way of coping with Subroc’s death. I didn’t want to be on the wrong side of history, and [the late producer J] Dilla had already done this with me on Madlib. When I realized that what DOOM was doing was therapy for tragedy — it had been so long since I had seen somebody in hip-hop not using it as a means of escape, or survival, or monetary means to get to the next level.

Open Mike Eagle: There was emotional rawness to it, and a rawness to his image and the videos of him that were coming out at the time. His clothes didn’t fit, and he was rocking this crazy bald spot while drinking a 40 on a bench. The whole thing was really just something else. There was a danger to it, but I didn’t realize that until way later. At the time, so much of the hip-hop I was listening to was overtly dangerous, and striving to come off even more dangerous. It was the Mobb Deep era, where these dudes were literally running around with goons and fighting people, and that was all in the music. It felt like this was a guy in a basement by himself, imagining something more and painting pictures with his words. He started out painting them really sloppy — quirky and kinda drunk —which was part of the appeal at first. Then, he started getting real precise. I don’t know if that went along with any change in his life, or if he was just on a quest to become a super dope MC.

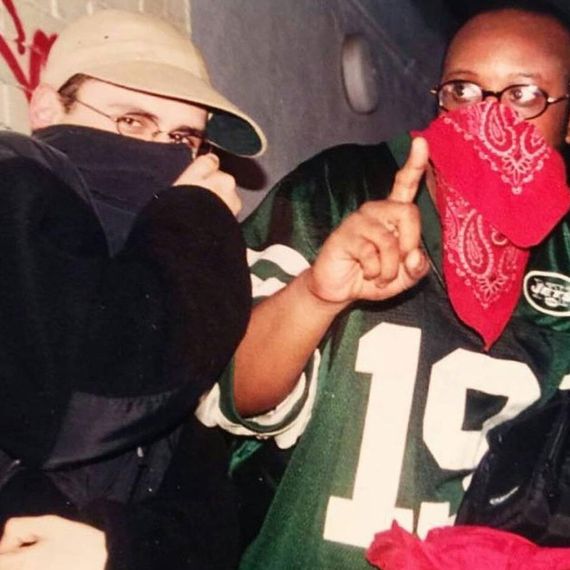

Nice & Nasty Vaz (DOOM’s former manager at Bobbito Garcia’s Footwork/Fondle ‘Em Records): Around 1998, I said, “Yo, DOOM, I’m doing this show at the Nuyorican Poets Cafe. Would you be interested in performing live?” And he was a little reluctant at first — this would be his first live appearance after his first solo release — until we talked about, “Hey, let’s not put you on the bill. Let’s make this a surprise performance.” And he was crazy open to that; he thought it’d be a dope idea to just get onstage and blow everybody’s mind. And we’re talking about a really tight-knit group of hip-hop heads; the line was around the block because I had a huge showcase bill.

He walks in smiling ear to ear because he sees how packed it is. Nobody knows who he is. He doesn’t have a mask on at the time; he’s just got a stocking pulled a little over his forehead and eyes with his signature red Phillies hat. I introduced MF DOOM and it was like, Holy shit. We’re about to get a live performance from MF DOOM. And the record was bubbling; “Hey!” was a huge underground hit in that community. So much so that I knew that when he got onstage and he started doing those tracks, the crowd was going to be mad hyped. So here he jumps onstage along with Megalon, with a stocking over his eyes and nose. He does “Greenbacks” for the first time, and even though the record hadn’t been out that long, 90 percent of the crowd knew every word to every fucking song he did.

I was just the right person, at the right place, at the right time. It was fucking magical.

Mad Meets Villain

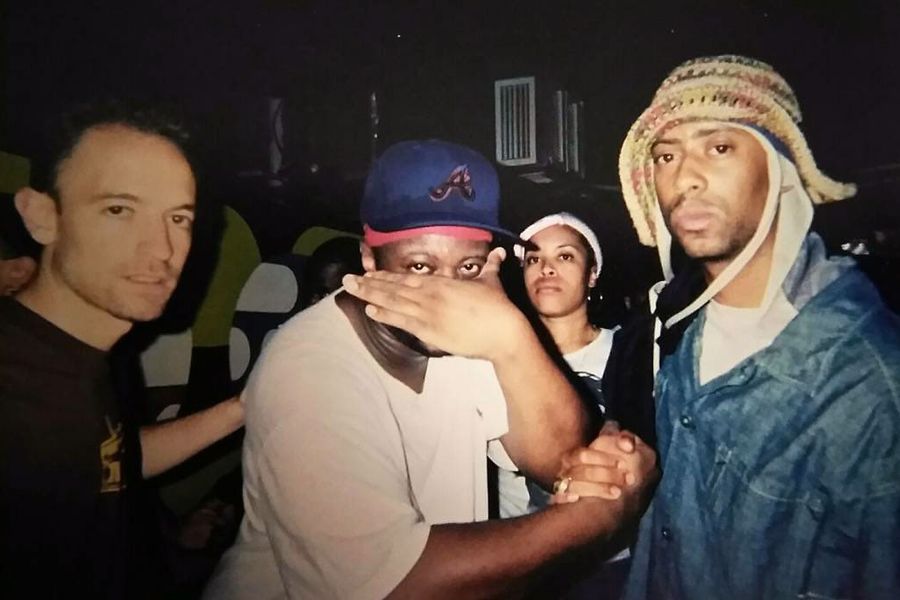

Peanut Butter Wolf: Even though he didn’t have mainstream success before working with [Stones Throw], DOOM still made me nervous because he was literally one of the only rappers at that time that we all really cared about. Everyone in the underground worshipped him and was trying to work with him, so it made me consciously not nerd out on him. I didn’t wanna be the annoying guy who made him wanna go back home early while he was recording Madvillainy.

I rented a three-bedroom house [in L.A.] at the time for me and two roommates, but Madlib moved in with us and stayed in a concrete-converted bomb shelter underground, which was also his studio. We’d all wake up to Madlib playing the drums every morning. I think DOOM really got to see a different side of this hip-hop producer and embraced it. DOOM rapped over a couple of Madlib’s jazz tracks, “Money Folder” and “Great Day,” that weren’t even supposed to be for the Madvillain album, but I think [the work environment] really opened his mind to what Madlib was really about. And DOOM, being an outsider, gave us ideas we weren’t even thinking about. And DOOM loved being around Madlib, so much so that he’d ended up staying with us instead of in the hotel that we got him and would just sleep on the floor or the couch. DOOM studied Madlib’s music and complimented it so perfectly, lyrically, and I think Madlib was inspired by knowing that DOOM and Dilla were both writing to his music. It made him step it up a notch and make some of the best beats of his career, and that in turn inspired DOOM to come up with some of his best stuff.

We were so happy with Madvillainy and ready to release it, and DOOM said, “No, I wanna go in and redo the lyrics for the whole thing.” We hesitantly let him go back and redo the whole album even though we already liked it — it actually turned out better. Most artists I work with don’t take the recording process that seriously. I never actually saw them in the same room together making music. Both had a different job to do in order to get it done. And even without much support from the press or radio at the time, it’s still our album that has resonated with the most people over the years.

Jason DeMarco (SVP/creative director for Adult Swim on-air): DOOM first came into the Adult Swim orbit when we were working with Brian Burton [Danger Mouse] on music. He asked if we knew MF DOOM, because they were talking about doing a record together and were thinking about doing a Toonami record, which is a block of action, anime cartoons that I run. I mentioned that a Toonami record might not work, but what about an Adult Swim record? He said that DOOM loved Adult Swim, and after talking to him, DOOM was immediately in. He loved Aqua Teen Hunger Force in particular. It was fairly easy to convince my boss to give us the money to make the record after playing DOOM for him, even though we obviously work at a TV network and the idea was kinda weird.

From there, it was really just supporting DOOM and Brian as they made the record. A lot of my job was not just getting all the Adult Swim voice actors together, but picking DOOM up for voice-over and music sessions. I was told to pick him up in the morning because he writes all night, and to make sure to bring a six-pack of Heineken. I’d be driving up to his place at nine in the morning, thinking, Are you sure?

Meeting DOOM and talking about old cartoons, while hanging out at his apartment and looking at his rhyme book that he had on his person at all times, was really how we got to know each other. We had a common language of old Hanna-Barbera and ’80s cartoons that we had both grown up on. He’s one of the best collaborations I’ve had creatively, and one of the very few people whom I consider a true genius. I’m really happy that we were able to expose him to a bunch of people who had never heard of him before.

Escapades of the Masked Wonder

Kathryn Frazier (owner of Biz 3 Publicity; worked on five DOOM projects): I can safely say that DOOM was the first real-deal eccentric in my ongoing 29 years in music. The antics were unprecedented even decades later as I look back, and I’ve worked [with] some of the most notorious fitful musicians in the game. In 2005, during the Danger Doom campaign [with Danger Mouse], we had a press trip that kept needing to be rescheduled due to DOOM’s penchant for not showing up for flights. I had a 1-year-old baby at home, and I last-minute asked a longtime Biz 3 publicist, Damon Locks, to go for me to cover this ever-moving press trip in NYC.

He begrudgingly went because his girlfriend at the time had flown into town to see him, but out of a sense of duty and honor to the team, he graciously went not knowing he was about to step into an incredible DOOM bait and switch. He and Danger Mouse awaited DOOM for the day of press, but alas, he was a no-show. The pair dined that night and Danger Mouse made Damon a $10 bet that DOOM would show the next day; Damon wasn’t so sure. The next day, an entourage showed up at the hotel where the press day was happening, but Damon didn’t [physically] see DOOM. He was told DOOM wasn’t feeling well and that he only wanted the photographer to come up to the room. This was odd, but he abided. This went on all day with several interviews and shoots, and [Damon] became more baffled and offended. They hustled through the day of press that had all been rescheduled multiple times and barely got it done, until Damon had to hop on a flight back to Chicago. He landed to the news from an upset editor that the creative director for the [defunct rap] magazine Elemental had zoomed in on DOOM’s eyes in the mask, and it was definitely not DOOM! The guy who did all the interviews and all the photo shoots, including a cover, was someone else!

Damon called me from the subway station and simply said, “I quit.” He was done; he had a gang of angry editors on his case accusing him of being in on this. A really sweet note from DOOM’s wife, Jasmine, smoothed things over for Damon, and he had a good laugh in the end. It’s hysterical lore now, the ultimate DOOM move. To this day the cover hangs in the Biz 3 office, although I suppose now I’ll have it encased in glass to protect this rare artifact of the escapade of the masked wonder.

Kool Keith (collaborator): A person like that is like no other. He was mysterious all around to everything. He was sending his vocals to me a lot and would text me from different weird numbers, like from area codes you never seen before in your life. It ain’t 213; it ain’t 323; it ain’t 305 — wild area codes I never ever seen. He matched his inside persona for the outside persona. It was like you were really working with Wolverine or something; like one of the X-Men is calling me out the blue sky.

Peanut Butter Wolf: Even though we lived together for a bit while we were recording Madvillainy, I didn’t want to interrupt his writing and recording process, so I kinda followed his lead when to hang out. But we’d go for food, or I’d take him to a smaller club or bar every now and then. We’d give the DJ a burned CD of whatever song we were working on and hear it on a big system, and the small crowd wouldn’t know he was in the room because he wasn’t wearing the mask. Honestly, only a few people in L.A. in the club scene even knew his music before we released that album. The only time we’d all really hang out together was when we had parties. One would think DOOM would hide and not socialize, but he was around. I’d have different friends through the years tell me, “That was so cool that I met DOOM at your Super Bowl party.” There was another party at our house where a guy introduced himself to me as Banksy, and I’m pretty sure he came to my house because he heard DOOM was at the party.

He was really a funny guy and also caring. The final line in the song “Accordion” used to be, “Wolf likes the girls with the skinny legs” because my girlfriend at the time was really thin. I showed her the song thinking she’d think it was funny and be flattered, but she started to cry. I explained, “No, he doesn’t mean it in a bad way.” Next time I saw DOOM, I told him about her reaction, and he didn’t tell me he was going to do this, nor did I ask him to, but next thing you know, he changed the lyrics. I guess he felt bad.

Jason DeMarco: DOOM definitely liked to cultivate a mysterious vibe about himself professionally, but he was a super nice guy and easy to work with. I think in his personal life, like being an hour late to open his apartment door, was just DOOM being DOOM. He just did his thing the way he did it. He was entirely self-motivated. I didn’t learn about his death until the news broke publicly on New Year’s Eve, but it was perfectly in line with how DOOM and his wife, Jasmine, managed his career. It felt very much like DOOM to do it that way. We had a lot of ups and downs, but you could never stay mad at DOOM for any reason. He’s truly one of the greats, and the reason that I kept going back to work with him again and again.

‘Long live Villain. Long live DOOM.’

Bishop Nehru (collaborator): It wasn’t that he was reclusive from the world. He was just more about music than anything else and put everything else in the background, made it on a need-to-know basis. That was the vibe I got when I met him, and got to know working with him. That feels normal. When we collaborated [on 2014’s NehruvianDoom] and got together in the studio, everything flowed naturally. I was such a fan of his music that I already knew where to take it, and what people would want to hear from his style. He put a lot of things to the side to focus on the project, and I really appreciated it. I first got into him when I was in middle school, and I was immediately a fan. He’s a legend that goes beyond hip-hop. He’s a legendary musician, poet, and artist, and had an impact on a lot of people without breaking himself, and I think that stands for even more. Long live Villain. Long live DOOM.

Questlove: Music hits different when someone leaves. You hear it different, and listening to all of his music in the past few weeks, I really wish I had immersed myself from the gate. I’m so ashamed to be telling this story because every person in my position wants to claim that glory: “I was there first! I put you guys onto it!” But no. Mos sat me down in the dead of winter, in January 2000, and preached the gospel to me, until I was late for a gig, to tell me DOOM was God. I’m sitting here, 21 years later, knowing what I should have known back then.

Open Mike Eagle: I’m still trying to break down every individual, minuscule, atomic particle of his style, and understand it. He made the best rap music ever. Period.

These interviews have been edited and condensed for clarity.

*A version of this article appears in the February 1, 2021, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!