“Call me Mike.”

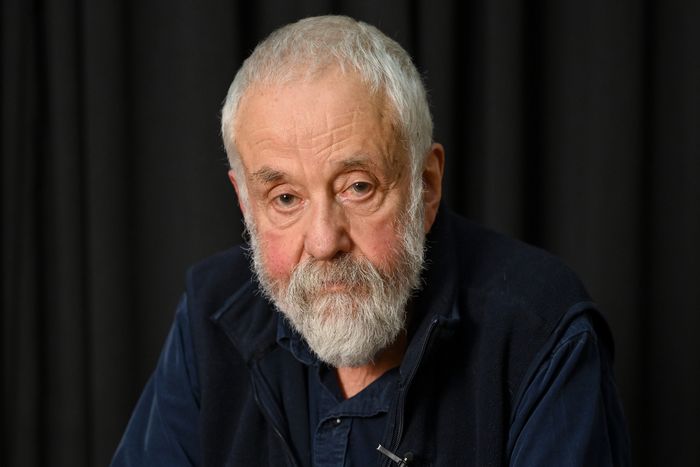

That’s what Mike Leigh, the 82-year-old director of such classics as High Hopes, Secrets and Lies, Topsy-Turvy, Career Girls, and Mr. Turner says when a journalist meeting him for an interview addresses him as “Mr. Leigh.” He is leaning on a cane, which he must use because he has myositis, a rare autoimmune disease that causes muscle inflammation and weakness. “I have to lean on this stick and ask people to help me stand up,” he says. “But I can get around all right.”

Leigh is standing near the elevator bank in a hotel lobby in the Flatiron district, doing one last round of pre-Oscar promotion in Manhattan for his latest movie, the domestic drama Hard Truths. Marianne Jean-Baptiste, Oscar-nominated co-star of Secrets and Lies, plays the heroine, a woman named Pansy whose bitterness and belligerence have turned her husband, Curtley (David Webber), and her son, Moses (Tuwaine Barrett), into nearly mute witnesses to their own lives and made Pansy’s only sister, Chantelle (Michele Austin), and her two adult daughters (Sofia Brown and Ani Nelson) worry that she’s cratering. Leigh and Jean-Baptiste have been nominated for many awards for Hard Truths and won the New York Film Critics Circle’s prizes for Best Actress and Best Screenplay. But Leigh says Hard Truths still faces an uphill battle for Oscar recognition because it’s a small film that lacks the bravura displays of scope, expense, and storytelling pyrotechnics that often mark a film as Oscar-able.

“This is mainly the story of a family,” he tells me as we step into an unpopulated lounge in the lobby. A publicist helps Leigh settle into a plush chair and brings in a tray with a tea set. The tea sits untouched through the first part of the interview. Leigh bats the first two questions down like shuttlecocks.

There’s a scene in Hard Truths where Pansy and Chantelle are in the cemetery visiting their mother’s grave and Pansy breaks down. It’s a very emotional scene, and at the end of it, Chantelle says, “I don’t understand you, but I love you.” I wonder if that’s any sort of guiding principle for you, in terms of presenting a best-case scenario of how humans might live together.

I don’t think so! [Pauses, thinks some more] No, it’s not. In all honesty, first of all, I don’t think in conscious terms. There is no guiding principle for me. Now of course I have a feeling about life and ongoing preoccupations, which obviously motivate and drive what I make. So in that sense, of course, there is a consistency, yes, because at the most fundamental level, the films do come from my feelings about and view of life as we live it, including the historical films. But there’s nothing conscious on my part about ongoing preoccupations or consistencies or running themes or any of that. I certainly never think about my other films at all. When I’m making a film, I don’t reference my other films in any way, any more than I make movies that reference movies, which obviously I don’t do.

Having said that: It may well be that what you’re saying is true, though in a way that’s for you to spot and identify. If you made me — and you’re not going to! — just go through all of the relationships in all of my films, I guess we could dig out very good examples of what you’re talking about. But equally, there would be other kinds of relationships where you really couldn’t do that. A whole lot of people have said that they feel like there is a connection between this film and Happy-Go-Lucky, down to the main character of this one being named Pansy and the one in Happy-Go-Lucky being named Poppy, but that never occurred to me.

But can you see why viewers might assume a connection between a sour woman in one of your films and a cheerful one in another because they both have flower names that are five letters long?

Never occurred to me! It’s funny, you know — people say, “Ah, obviously this is Pansy, the flip side of Poppy.” But it’s rubbish, really. A writer of the character expresses something about her energy by naming her Poppy. When we christened Marianne’s character “Pansy,” there was something ironic about it, something kind of … well, contradictory. Those are really two different kinds of decisions.

I bet that if Poppy encountered Pansy during her travels, she might be the only person who’d know how to talk to her.

Oh, true! That’s not in question. If we put them together, Pansy would give Poppy a hard time, but she’d laugh it off or let it pass while having learned something about Pansy.

Have you ever said to yourself, These two characters in these two films of mine seem linked in some important way?

After making Happy-Go-Lucky, I realized that there was a similarity between characters in two of my films: Poppy in Happy-Go-Lucky and Johnny in Naked. They’re both idealists, but he’s a frustrated idealist, a disappointed idealist. Poppy is an idealist who meets a situation and deals with it and acts on it and who is able to. But each film is its own thing, and each character their own thing. It’s an ongoing investigation.

I first interviewed Marianne 23 years ago, when she was working on Without a Trace, and I asked her about your process. She said, “Mike grows a film.” What do you think of that?

First of all, you should go ahead and have some tea. [Indicates the teakettle]

Yes, sir.

Painters paint pictures. Novelists write novels. Poets write poems. I embark on this journey of discovering what a film is through the course of making it. So yes to that description. Growing a film? Yeah. I mean … It does all start with, in principle, nothing: some loose ideas, possibilities. Sometimes I know more about what we have in mind than other times. Then we react to it and then it grows. That’s really how it works.

If you’re growing a film, what is the seed?

There are different kinds of answers for different films. For example, if you like, let’s take Secrets and Lies and Vera Drake. Secrets and Lies very specifically arose from the fact that there were couples in my family who adopted kids. So I thought, I’m going to deal with this, actually. When I started to look at it, I realized that I wasn’t going to make a film about people who adopt, but a baby that’s been given away and finally meets the birth mother. So that was the starting point for that film. There were other things I then discovered, such as: In the 1960s, a lot of white working-class girls gave away mixed-race babies.

What was the seed for Vera Drake?

Vera Drake started from the fact that I’m old enough to remember what it was like in the U.K. before the 1967 Abortion Act, when people had unwanted pregnancies and had to go to illegal abortionists. I sat on the idea for 40 years or so. So I do have, sort of, I guess, ongoing preoccupations, and I have certain kinds of notions, and they can be a starting place.

But to start to really answer your earlier question: I start with the casting.

In the case of this film, Marianne, as you know, lives in Los Angeles, but we’ve kept up, and we see each other from time to time when she’s in London. Working together again sounded appealing, and we really felt we had to do it. We were actually going to do the film in 2020, but COVID scuttled that. But Marianne was the first.

What about everyone else?

All the actors I work with are, and have to be, consummate character actors. By character actors, I mean: This is not the business of people coming in and just being themselves. Then following on from that, we thought, Let’s see if we could get Michelle Austin, because Michelle and Marianne have been a duo before and have a good dynamic, and it’s time to give Michelle a bigger slice of the pie than she’s had in several of my other films.

What is the process like, devising characters and a story in collaboration with actors?

I always start by individually asking the actors I work with to make a comprehensive list of all the sorts of people they know. We then talk about those and then pick some, and we distill those into a character. One difference on this film is although I had Black characters dotted around the movies over the years, it was a given that if we were to make a film that focused more specifically on Black people than I had in the past, everything would need to be accurate. Potential names always have to be specific for the cultural background of a character. Pansy and Chantelle — and indeed most of the other names in the film, such as Curtley and Moses — are all names that are accurate for people from a British Jamaican background.

Parallel to that, as you know, I am consciously and subconsciously tapping into ongoing preoccupations. I mean, most people who have seen the film — and this may include you, I don’t know — will say to me, “I know a Pansy.”

I know a Pansy. I bet everyone does.

Absolutely, there you go. And I know a Pansy. So you start to resonate with that, you know? But as for the process of growing a film, how many novelists have said, of the process of writing one of their novels, “I didn’t know what was going to happen next but then I realized it was this”?

All of them.

That’s what happens when you’re interacting with material. Where our types of films are concerned, there’s an element of discovery, of not knowing, just as if you’re just sitting down at the typewriter or the computer. You don’t know where the story is going to go until you’ve gotten there. When I talk to film students, they say, “What do you think about the three-act structure?” I say, “Well, actually, I don’t think anything about it.”

Why, because it’s too limiting?

No, because you can’t help but have a three-act structure, whatever you do! In any kind of storytelling, the steps are: You establish a thing, you challenge it, and you resolve it. That’s a three-act structure! It’s organic. There’s a point in our process where the story assumes that structure. On this film, for example, we had 14-week session of creating the characters and investigating and building their relationships and doing research and working with the production designer and the costumer to plan how things will look, and at the end of all that, I then sit down and write a sort of three-page potential structure. Sort of a blueprint.

What was the very first step?

Marianne made a long list according to my instructions of real people, women, that she knows and has known — not necessarily women that she’s known well, just various people. Then with Marianne, and all the main actors, we did one-on-one sessions, with nobody else there, and worked on all the character lists individually some more. Then I said, of the lists of various people, “Let’s get rid of her” and “Let’s get rid of her.” Through this process, we arrive at — usually, and in this case — a list of three people. And then, by means of some esoteric process, we meld them together. And that gives us a jumping-off point, a source character, an embryo character.

So we’re making the characters by talking them into existence and also by doing some actual, practical, physical acting work to make the basis for the character. As we start to build it and grow it, we start to make decisions about all kinds of other things: real life decisions, character decisions, relationship decisions.

And it’s then you give birth to Chantelle and you start to put her and Pansy together. We explore their relationship pretty much from the point when Chantelle was born, because that’s where you have to start the story, logically. If you want clues to what I’m talking about, they’re revealed in the cemetery scene.

The part about their childhood, and their dad leaving the family?

Yes. Then we get to the stage where, through rehearsal, we are scripting and deciding exactly what we then have.

What was the most enjoyable part of the character-shaping process for Pansy?

Marianne and I had a ball building up Pansy’s invective. And of course, this is a woman who says very funny things but has no sense of humor. Marianne and I have an enormous shared sense of humor. And Marianne couldn’t do that character if she wasn’t a really funny woman herself, and very perceptive and sensitive to life.

What we didn’t do was set out to make a difficult person, because, quite frankly, I wouldn’t know what the fuck that would have meant! And even if a screenwriter sat in a room and made that decision first, they’d still have to do the thing of creating an organic character, with nuances and levels.

I have a question about the improvisational development process in your historical films. When your actors are in a period film, do they improvise in rehearsals based on historical research? By which I mean, does every ad-lib have to be footnoted, in a sense?

On the historical films, yes, everybody does a lot of research. Topsy-Turvy was like a mini-university. Everybody, not just the actors, had to research the period, not just Victorian theater, music, culture, but politics, religion, you name it. People read Victorian newspapers of the period. We had ample supplies of back numbers of Punch magazines from that period, so that people could get their heads around the language. I had a chopping trolley with me all the time, loaded with various texts and pictures. Similarly enough, I think the volume I referred to more than any other in fixing the dialogue was the Savoy operas by W.S. Gilbert, because the approach to the phraseology and the irony was very much laced into that. At one point we had etiquette workshops.

The processes were the same on Mr. Turner and Peterloo. Incidentally, on Peterloo, where the actors were going to have to play working-class northern characters, I made a very strict decision beforehand that I would not cast an actor who wasn’t from the north of England. We found a volume written at the beginning of the 19th century that was a dictionary of Lancashire working-class dialect, and it became a bible. You can do anything as long as you approach it and research it.

I wanted to go back to the comment you made about the three-act structure. Yes, I can see a three-act structure in all of your films, to some extent. But they don’t adhere to the idea that every moment must further the plot. We’ve never met Maurice’s ex-partner in Secrets and Lies until the scene where he shows up at the photography studio to talk to Maurice and we see what a train wreck he is, yet you give that guy a spotlight for several minutes. I loved it, but as you know, there are people who think that scene is a tangent that should have been cut for time.

Our French backers wanted us to cut the scene you mention, and also the scene with Hortense and her friend, because they thought they were both irrelevant. We fought a massive battle with them. We won the battle. They didn’t want us to go to Cannes, but we went to Cannes. And we won the Palme D’Or with those scenes in the movie. The scene is important because you see Maurice dealing with this guy. If you didn’t have that scene, there would have been no other opportunity to see Maurice dealing with somebody, and with issues, in a way that’s important to know about when you finally get to the end of the film and a revelation comes. So the scene has a function on that level as much as any other.

But what you’re also talking about, and there are plenty of examples of this in Hard Truths, is the importance — or the bonus, if you like — of seeing absolutely rounded, three-dimensional portraits of very minor people who, on the whole, would otherwise appear to have nothing to do with the case, really, like the girl in the furniture shop, and the guy in the car park, and the people in the supermarket.

And the customer who can’t get through a hairdressing appointment without taking a cigarette break.

Absolutely. And the earlier customer who’s just been on night duty and saw somebody die, you know, and has got problems with their elderly husband screwing young ladies and all the rest of it. Those latter two examples are, of course, the same as the scene in Secrets and Lies about Maurice dealing with that guy. Both those scenes in the hair salon are about Chantelle and her generosity and her ability to listen to people and care about the stuff they’re going through. The scenes are multilevel in their function.

I briefly thought about Maurice while watching the cemetery scene in Hard Truths. After the sisters’ father ran out, Pansy was forced to take on responsibilities she wasn’t ready for. If Maurice had kept going down that road of trying to be the glue holding his extended family together, might he have ended up as bitter as Pansy?

I don’t know about that. I would have personally thought that Maurice is naturally disposed to be generous, and I can’t really see that in Pansy. But trying to answer that kind of question is like when people get to the end of the movie and ask me, “All right, but what actually happened?” That’s over to you. “What is it? Why? Can you explain why Curtley throws the flowers out?” No. That’s over to you. I’m not in the business of doing that. It’s over to you, the audience.

I can’t recall any movie of yours where you’re flat-out telling people what to think. But I can think of some of your films that are more straightforwardly political than others. Peterloo, for sure. And Naked.

On Naked: That’s your prerogative to see it that way. I made three films consecutively which I then realized were more overtly political in certain kinds of subtle ways than any others, and they were made consecutively. They’re in the Criterion Collection now. One is Meantime, which came from the conditions of unemployment under Thatcher. The second is Four Days in July, which is about Northern Ireland and therefore implicitly political. And the third is High Hopes, which deals with the thing, apart from the other things it’s about, where you have to cope with your conscience about whether to act on what you really think. That’s what the sexual character Cyril’s dilemma is. Having said all that, the only film of mine that is more obviously concerned with the political is Peterloo, by definition.

Let’s talk about the filmmaking!

Did you know that Dick Pope, who shot most of my films, has died?

Yes, sir! I wrote an obituary for him.

Oh, you did? Yeah — I think I read that, actually. Massive loss. He was a great guy, you know, and a great, great artist, a great collaborator: I would say irreplaceable. But wherever he is, he’s sending a message saying, “You got to find somebody else.” And I will. But it’s a tough proposition.

What did you learn from working with Dick Pope?

We learnt from each other. I first worked with him on Life Is Sweet in 1990, and he shot everything I’ve done ever since, including minor stuff. I’d already worked with other cinematographers, including Roger Pratt, who also died recently, on the first of January. The way we shot Life Is Sweet was pretty straightforward. But the next film was Naked, and I sort of said to him, and to the designer, “I think this is about a guy on a lone journey. It’s perhaps nocturnal, maybe it’s monochromatic.” Knowing that we were going to shoot on Eastman film stock, Dick shot tests. He came up with this idea of doing a bleach bypass, which misses a little bit of the process in the lab. It was a great idea that was perfect for the movie because it gave it a grayness.

From then on, in every film that we made, his preparation consisted of experiments, to the extent of finding a company that would manufacture Victorian theater light bulbs for the shooting of Topsy-Turvy. When we got to that stage with Happy-Go-Lucky, I said, “You know, it’s somehow primary colors.” He said, “Okay, I’ll think about that.” And a few days later, by coincidence, there was an annual film-industry market in London. Fuji had a stand, and they had a new stock called Vivid for primary colors. And Dick said, “This is amazing. I’m making a film with Mike Leigh,” and they were so amazed to find anybody who wanted their stuff that we got it for free!

Another interesting thing about Dick, which you’ve written about, is that for long stretches of time before we met in the early days, he shot World in Action documentaries in obscure parts of the world. He took hidden cameras into dangerous places. He shot in the Far East. He shot in the desert. And he also famously shot music videos for big stars. But the documentary thing is important, because Dick had a real sense of real shooting in the real world. It would have been inappropriate for a cameraman, a cinematographer, to approach the kind of material in my work with documentary naturalism, so it’s heightened and distilled. But he was absolutely on the case.

Do you often have to cut scenes from your movies for pacing or running time or other reasons after you’re finished shooting? Or have you mapped things out so thoroughly beforehand that you know what you need before you get on set, and you’re mainly executing a plan?

For the most part, what we take to the cutting room is pretty well organized and distilled. We cut two scenes from Topsy-Turvy because it was running very long, and there was a big battle about it. Those scenes are tacked on as extras on the Criterion version of Topsy-Turvy. And there are scenes which you finally get to the editing and go, “Actually, you know what? The movie is better without this scene.” When we shot Secrets and Lies, and we were doing the research for Maurice, Timothy Spall and I spent a whole day with a High Street photographer working a wedding. We were very taken with the whole possibility of that, so there is a scene in the film where you very briefly see Maurice in a church. But there was also a whole other sequence where he’s going around a house with the bride and the bridesmaids. In the cutting, when it came down to it, we realized, “This is a red herring.”

I wanted to ask you about your blocking of your actors, particularly in scenes with lots of characters packed into the same frame. For example, in the cookout scene from Secrets and Lies.

That’s the famous, big one, it is.

The way that you and Pope position the actors in the frame, we can see everybody, but somehow it doesn’t feel like it’s blocked.

Well, that’s exactly the objective. If you said, “Well, let’s just let this happen, very natural, as if it’s all going on,” it would be an absolute fucking mess. So we spent days rehearsing that scene to make it look natural. Hardly anybody in the scene overlaps the dialogue, but when it happens, it’s a deliberate thing. Maurice is doing the barbecue and his wife, Monica, is serving up. Once she gets up, she sits down, they pass the salt. And at the same time, you wonder what’s going to happen. Is something going to spill the beans about why Hortense is there? All that is going on. But it’s absolutely all controlled, rehearsed very thoroughly — except that you can’t direct a steak. Steaks have a will of their own and may jump off the plate. But we’re talking about something that’s very straightforward. It’s about rehearsal. It’s about just painstakingly, meticulously building it and getting it right and never compromising the actors in character or their motivations.

The whole process starts with improvising, so by the time we shoot a scene like the cookout, the actors are all naturally where they need to be, in terms of the character work. So my main job is to say, “You’ve got to be over there and you’ve got to be over here, because otherwise we can’t see you both in the frame at the same time.” But the blocking is never unmotivated. In Hard Truths, the Mother’s Day scene in the kitchen after the cemetery scene is a bit like the cookout scene, in that way. The actors are close together and carefully blocked.

It’s a powerful scene, both for your leading actor’s performance and the wordless reactions of the others as Pansy implodes.

The moment where Pansy suddenly breaks out into mirth which turns into tears could not come into existence by any means other than really grounded, thorough, motivated improvisations. I couldn’t sit in a room and write that in a zillion years. Nor could Marianne and I sit in a room and talk it into existence. Nor was there any precedent for that at any stage prior to that moment when we were building the sequence. But when it happened, it was dynamite! The motivation was so dense and complex.

Why does this movie have two identically framed lateral tracking shots in front of the house where Pansy and her family live, at the beginning of the story and also pretty close to the end?

The honest answer is that it just seemed the natural thing to do, you know: In the first of those shots, you follow Curtley, who’s a contractor, and Virgil, the guy who works for him, as they get into the van and drive off down the road. And then what? We move back toward the house. What we’re saying there is “Those two have left the house, and now we need to go back to this house and hold on it, because obviously something’s going to happen inside,” and that’s exactly what occurs. That’s the motivation for that first shot. At the end, Virgil comes out and gets into the van and drives off. We are referencing that earlier shot. That’s because we know Pansy and Curtley are inside — and that she’s upstairs and he’s downstairs. We’re doing the same thing with the camera: By moving back toward the house, we’re saying — again! — “I wonder what’s going to happen when we go inside.” And then we go inside and find out.

And inside the house, everything has changed.

I want to tell you something interesting about those two shots of the front of the house. When we shot the earlier one toward the beginning of the shoot, early in the schedule, there was a big tree in the shot as the van drove up. Before we did the second one, we had to go to another location, and while we were away, the council came around and chopped the tree down. So that tree isn’t in the second shot! When we did the second shot, somebody asked me, “Should we add the tree back digitally?” I said, “No one’s ever gonna notice.”

I bet somebody’s gonna write a thesis about the hidden meaning of the missing tree.

I look forward to not reading it!