There have been lots of movies about pigs over the years, but rare is the movie that lets the pigs onscreen just be pigs. More often than not, the animals are anthropomorphized or metaphorized. (That’s not always a bad thing. There will be no Babe: Pig in the City bad-mouthing here, thankyouverymuch.) But Viktor Kossakovsky’s mesmerizing documentary Gunda still serves as a bracing corrective to the way animals are usually portrayed on film. Its earthy radiance reminds us of what we’ve been missing in our need to see ourselves in these creatures, instead of seeing them as themselves.

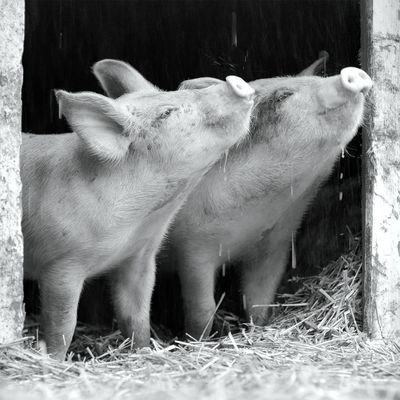

The film opens with the titular sow, impeccably framed through the entrance to her sty, as she gives birth, her tiny piglet babies crawling all over her (and each other) to get to her teats. The piglets are, of course, adorable, and their quick, jerky movements make a sharp contrast to their lumbering, exhausted mother; it’s as if parent and offspring are operating at completely different frame speeds. Over the course of the picture, the piglets grow and play as Mom pushes and prods them along.

These aren’t the only farm animals we’re introduced to in Gunda.

There’s also a one-legged chicken clucking and doggedly traipsing around, as well as a herd of cows thundering and lolling about. There’s no real connective story line, other than the immediacy of what’s onscreen. The documentary was shot in different locations, so we can’t even say these animals all belong to the same farm. Something does unite them, however: They belong to that shared spiritual domain we might call the Place Where the Animals We Eat Come From.

Kossakovsky has an idea here, and it’s a good one: He wants to establish a connection between us and these creatures that we think of primarily as food, but he doesn’t want to do it at the expense of truth. To try and give them human personalities or traits would be not just dishonest, but counterproductive; it would make the whole movie (and any message its maker may want to convey) dismissible as fantasy.

So we don’t necessarily understand these animals. We are, however, transfixed by them. Lingering close-ups of their faces make us wonder about their inner lives, while our elemental connection to the textures of this world — to the mud on their bodies, or to the way they scramble up and around various obstacles — create a one-to-one physical connection. It’s the damnedest thing. You would expect the movie to establish a story thread or some kind of narrative through-line, however subtle, to keep us going. But Kossakovsky just lets this world be, which feels like an act of radical honesty. He respects the animals’ being, and he respects our intelligence.

Usually with this sort of project, especially one so visually accomplished, we’d hear stories about the acres of footage filmed and the years spent producing the movie, getting every frame and cut just so. But Kossakovsky has gone on record as saying he shot relatively little footage (partly because celluloid film is itself made from animal byproducts and he wanted to keep its use to a minimum) and for a relatively brief period of time. He and his crew spent a few days shooting the piglets and then came back a month later for a couple more, and then again a month after that. (The film is executive produced by Joaquin Phoenix, an outspoken vegan, who reportedly connected with the director after his memorable Oscars speech last year, in which he railed against humans’ disconnection to and plunder of the natural world.)

The sheer elegance of Gunda’s imagery, however, does not scream simplicity. Kossakovsky may not anthropomorphize his subjects, but he does aestheticize them. The elegant tracking shots, the careful framing, the insistence on remaining eye-level with these creatures — not to mention the complex, wordless sound design, made up of grunts and squawks and clucks and stomps and splashes — all help to immerse us in the world of the animals. At times, Gunda feels like the kind of movie they might have made about themselves.

That in turn makes one particular late-film development enormously affecting. I won’t “spoil” it, though even to speak of it as something that can be spoiled, as if it were there merely for our narrative amusement, feels obscene. You can probably guess the nature of what I’m talking about, but you should also know that it’s not graphic or overt. That doesn’t make it any less shattering. In fact, it might make it more so. We don’t see, and we may not even entirely understand, what’s precisely happening during such moments. And, well, neither does Gunda.