If you’re going to make your film debut in a high-school sex comedy, you could do a lot worse than Fast Times at Ridgemont High. The eminently quotable 1982 classic gave Nicolas Cage his first film role, alongside rising stars like Sean Penn, Judge Reinhold, and Jennifer Jason Leigh.

But for Cage — then credited under his birth name, Nicolas Coppola — the experience was as anticlimactic as Stacy (Leigh) and Damone’s (Robert Romanus) poolside romp. An unknown 17-year-old from Beverly Hills High, Cage received only a bit part in the film after losing the Brad Hamilton role, for which he had auditioned multiple times, to the older Reinhold. Not only were Cage’s talents underutilized but he endured mocking from his fellow cast members, who teased him for being the nephew of Francis Ford Coppola. Cage soon resolved to break out from under Coppola’s long shadow with a new name.

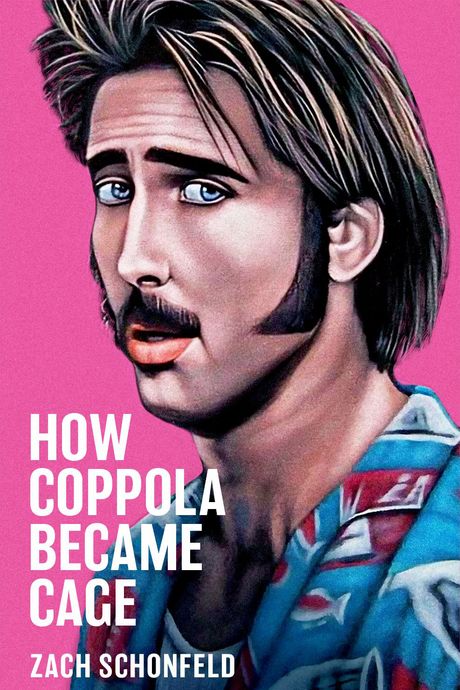

This excerpt from my new book, How Coppola Became Cage, delves into the actor’s tumultuous experiences on the set of his first movie. For this passage, I drew on original interviews with Fast Times director Amy Heckerling, actor Eric Stoltz, Heckerling’s then-assistant Carrie Frazier, and the late casting director Don Phillips. The book as a whole draws on more than 100 interviews with Cage’s associates and collaborators to chronicle the story of this icon’s early career and rise to fame.

Fast Times at Ridgemont High was supposed to be Cage’s big break. The mother of all high-school sex comedies, that movie seemed to be everybody’s big break, a kind of hormone-heavy incubation center for ’80s movie stars. Fast Times helped establish the careers of Sean Penn, Jennifer Jason Leigh, Forest Whitaker, and Judge Reinhold, and it marked the feature-film debut of future Pulp Fiction drug dealer Eric Stoltz.

It marked the film debut of Cage, too, though it feels like a technicality to say so: He appears onscreen for all of 20 to 30 seconds, delivers no real lines, and was credited as Nicolas Coppola for the second and last time.

Fast Times at Ridgemont High arrived in 1982, one of the historic transitional years for American cinema. Plenty of great movies came out in 1980 and 1981, but 1982 was when the cultural category of the “’80s movie” really began. It was the year the dream of the New Hollywood era collapsed in the flaming wreckage of Francis Ford Coppola’s overpriced passion project One From the Heart. It was the year an aspiring filmmaker named John Hughes landed his first film credit (albeit as writer, not yet director). And it was a moment when teenagers were beginning to dictate, more than before, the kinds of movies that studios would make.

As the critic Dana Stevens writes, 1982 was “the dawn of a new golden age of what were then referred to, with some derision, as ‘teen exploitation movies.’” Hit comedies like Animal House and Caddyshack had helped bring a raunchier sensibility to the box office, and younger audiences were ripe for targeting. The genre’s commercial potential had been revealed by Porky’s, a comedy about the “sexcapades” of teen boys in Florida, which became one of the highest grossing movies of 1982.

Fast Times, with its frank depictions of horny high-schoolers learning fellatio techniques and exploring sex with each other (and, in one unforgettable scene, themselves), soon followed. It seemed primed to be another teen-exploitation bonanza but turned out to be much more: a quotable classic, an unexpected star-maker, and the rare film that neither elides nor glamorizes the awkwardness of early sexual experiences. For this reason — and the film’s empathy with its female characters’ discomfort — Stevens argues that it’s “the polar opposite of exploitation.”

Fast Times at Ridgemont High is an ensemble comedy, chronicling a year in the lives of teenagers at a fictional California high school, including the sexually inexperienced Stacy (Jennifer Jason Leigh), her well-liked older brother, Brad (Judge Reinhold), and the delinquent, perpetually stoned Jeff Spicoli (Sean Penn, lightening up for once). The screenplay was written by Rolling Stone journalist Cameron Crowe and based on his 1981 book. Crowe posed undercover for a year at a San Diego high school, pretending to be a student while secretly lapping up character ideas.

After writing the screenplay, Crowe offered the project to the director everybody associates with upbeat sex comedies: David Lynch. The Eraserhead director read the script and politely turned it down, correctly surmising that this wasn’t his type of movie. Crowe found a better fit in Amy Heckerling, a punk-rock fan from the Bronx who had recently graduated from the American Film Institute. He watched her thesis film, about a girl desperate to lose her virginity before turning 20, and liked her sensibility.

At the time, teen movies weren’t regarded with much respect, and Universal Studios was pressuring Crowe to include more grown-up characters in Fast Times so it would appeal to adults. He resisted. In Heckerling, he found someone who shared his vision of a movie entirely about young people and for young people, an unmediated glimpse of Southern Californian adolescence, where social status is defined by what car you drive and where you work at the mall. “It was like, here’s that world they function in,” Heckerling later reflected. “Here’s what you grown-ups don’t see.”

Cage was 17 — an ideal SoCal specimen — and desperate for a breakout role when the movie entered production in 1981. He became a leading contender to play Brad Hamilton, the cocky high-school senior who works a demoralizing fast-food job and fantasizes about his sister’s attractive best friend. “I must have auditioned for that part 100 times and I thought I was going to get it,” Cage recalled in a 2021 interview.

So did casting director Don Phillips. “A lot of people read for that part,” Phillips said in an interview conducted shortly before his death. “But Nick was head and shoulders above all the Brads.” Phillips interviewed Cage early on and was impressed with what he saw: a good-looking kid, tall, very polite. “At that time, he was Nick Coppola,” said Phillips. “Of course, I think that’s the reason he got in to see me, because he had no credits except in some play at Beverly Hills High.”

Inexperience wasn’t a problem. With minimal budget for cast salaries, Phillips, a casting guru later credited with launching the careers of Mary Steenburgen and Matthew McConaughey, was determined to find unknowns. “I saw something in Nick that was special. And I thought he could be the perfect Brad,” Phillips said. “Brad was a little inexperienced with girls, with studies, with work. I saw that [Cage] had a lot of those qualities. He was new and he was young and he was ambitious.”

“He wasn’t a traditional, good-looking American boy,” says Heckerling’s then-assistant, Carrie Frazier. “But there was something that was so engaging and so soulful. I felt like he was somebody who could [play] wounded very easily.”

Phillips told the film’s producer, Art Linson, that they had found their Brad. The next step was for Cage to read for the part in front of Linson and Heckerling. “Nick came back and he read great,” Phillips said. “He was wonderful. I said, ‘He’s the one! I’m right!’ Amy kept hesitating.” Cage returned and auditioned again. “Amy kept rejecting him. She really wanted Judge [Reinhold],” Phillips says.

Heckerling, however, maintains she wanted Cage too. “There was no other contender. He was the only one I was considering,” the director says. “There was something so lovable and goofy about him. The part was somebody that thinks they’re hot shit, but you would sense the vulnerability. I felt like that was just there perfectly.”

So why didn’t he get cast? Heckerling is deliberately vague on this question. She was told, “after seeing many people and calling back Nick repeatedly, that I couldn’t use Nick.” (She won’t say who issued this decree or why.) “And then I was desperate,” Heckerling adds. “I was like, ‘Oh God, let’s call in Judge.’” Reinhold was a friend. He lived in her building and was dating her close friend and assistant Frazier. Like the stars of many era-defining high-school movies to come, he was in his mid-20s — practically a lifetime removed from high school — yet willing to play a teenager.

Cage had come within inches of his first big role, but despite Phillips’s protests, Reinhold got the part. Heckerling would later say this was a practical decision: Cage was underage. “We wouldn’t be able to work with him as many hours as we could with people that were 18 and over,” the director said in a 1999 featurette. Today, though, the director maintains that Cage’s age wasn’t a factor because he misled them into thinking he was 18. (Cage has denied that he ever lied about his age.)

As a kind of consolation prize, Heckerling gave Cage a smaller role as “Brad’s bud,” a nameless side character who works alongside Brad in the fast-food joint. “He was wonderful,” the director says. “He did want to do a bunch of improvs, and some of them were a little kooky. He’d say something, and the crew would look at each other like, ‘What?’”

Eric Stoltz recalls messing around with Cage and other actors outside their makeshift trailers. “We were a bunch of young teenagers, most of us doing our very first movie,” Stoltz says. “Just like high school, we settled into our various cliques. The lead actors were working most of the time. But us smaller roles, we spent a lot of our days sitting around the honeywagons. And while we were hanging out and waiting, we would take the piss out of each other and goof around.”

The shoot proved formative for the film’s stars, but it was miserable for Cage. Other actors mocked him for being a Coppola. The experience helped motivate his decision to shed his troubled surname. “I was pretty much the nerd to everybody,” Cage later told Entertainment Weekly. “I was the brunt of jokes because my name was still Coppola, so there’d be a congregation outside my trailer quoting lines from Apocalypse Now, like, ‘I love the smell of Nicolas in the morning.’”

In multiple interviews, he singled out Stoltz as a source of particularly merciless teasing. Forty years later, Stoltz is surprised to learn that he’s part of Cage’s origin story, but he does have regrets.

“Nick was one of the younger ones,” Stoltz says. “He was big for his age, and he was quite bold and animated. In the midst of all this hanging around, on occasion he would drop his uncle’s name. Which isn’t a crime, but it didn’t feel very good. So we would give him guff about it until he stopped.”

“I remember us all laughing and having a good time,” Stoltz continues. “In retrospect, we were undoubtedly envious of his God-given Hollywood access. And he was probably a bit insecure behind all that bravado. But I certainly didn’t have the maturity to understand any of that. So yeah, I did take part in the teasing and I’m sorry I did. I do hope that didn’t cause him too much pain.”

More From This Series

- Marshall Brickman’s Best Advice for Aspiring Comedy Writers

- I Thought the Sun Rose and Set on His Sicilian Ass

- Enjoy J. Smith-Cameron’s Martini-Themed Crossword Puzzle ‘With a Twist’