The first image Patti Smith posted on Instagram in 2018 was a photograph of her hand, palm up, fingers outstretched, a thin gold band at the base of her middle finger; it was set against a white wall with a narrow line of wainscotting along the right side and a small crack in the bottom right corner. The gesture could have been swearing an oath or waving hello or perhaps meant to serve as both. The caption simply read, “Hello Everybody!,” her favorite way to greet the internet.

What could have become an account that provided a pleasant but unremarkable series of tour images instead evolved into a new outlet for Smith’s ongoing relationship with her audience. Her Instagram is a lyric poem writ digitally, and she intuitively figured out how to compellingly work in that new medium. It was only logical, then, to package so much of what is delightful about that digital presence into an analog format with the exquisitely curated A Book of Days, her recently released collection of 366 images, one for each day of the year (including a leap day), accompanied by concise, elegant captions.

Smith explains in the book’s first entry that the primary reason she joined Instagram was to counter the fake Patti Smiths that were running amok on the service. But once there, she embraced the routine, regularly posting the same kinds of everyday things the rest of us put on our main feed: photos of her cat, her backyard in the snow, her children smiling, endless cups of coffee, lunches with friends, artifacts around her house. She recognized that it was another way to communicate directly with her fans, which is something she has always done in one form or another.

In the early days of her groundbreaking punk band the Patti Smith Group, there were moments at a reading or a concert where she’d break into conversation with the audience; not just responding to the types of “We love you” or “Play ‘Free Money’” types of yelps but actual discussions where she asked what people were listening to or admonished them to drink hot tea after being caught in the rain. If fans couldn’t get to a concert, both the official fan club’s P.O. box (handled by none other than Patti’s mom, Beverly) and a fan club that put out a zine were listed in album liner notes. These outlets existed because Smith (and her guitarist Lenny Kaye) were themselves enormous rock-and-roll fans, so they knew how much it would mean to the kids in the crowd to have a direct connection. These days, fans can comment on her Instagram posts. Smith reads it all, even if she doesn’t respond.

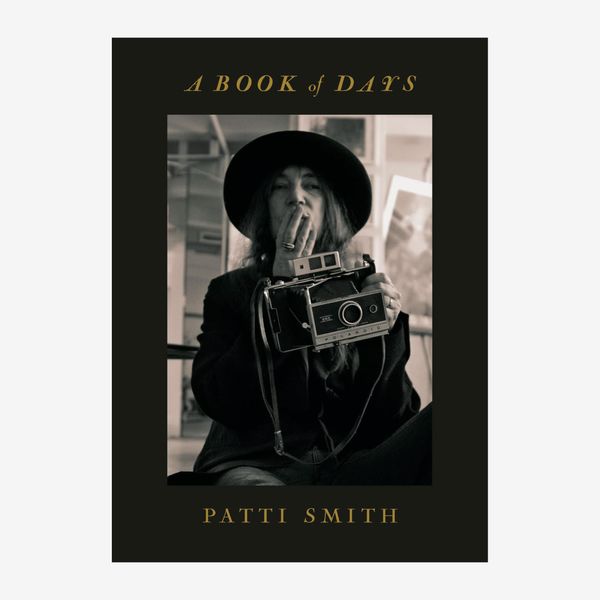

A Book of Days is a collection of images and texts presented in a smaller-than-standard-size book, a nod to the small, square (or rectangular) frame of Instagram and Polaroid images. But it’s not an export of her Instagram; the entries in the book are more polished. The image on the cover features Smith holding her beloved but retired Polaroid Land 250 camera, the one that launched her foray into photography that began after the unexpected death of her husband, MC5 guitarist Fred “Sonic” Smith, in 1995. “I felt so weary,” she told Reuters in 2008 on the occasion of the first exhibit of her images at the Fondation Cartier in Paris. “I was unable to write or draw. Taking Polaroids because it’s so simple, immediate, gave me an immediate response to my creative needs, it was helpful to me to restore my confidence as an artist at a very difficult time.”

Later, she took the Polaroid on tour as she returned to public life as a performer. A famously light packer (a fact she illustrates here and here), she liked having the camera on the road because it gave her motivation to leave the venue or the hotel. Churches, ancient buildings, museum artifacts, and countless tombstones, sculptures, and gravesites were among Smith’s favorite subjects, and the images punctuated her books and album artwork. Once it became impossible to find film for her particular Polaroid, Smith embraced the convenience of an iPhone — for someone who tours with one small suitcase, it’s certainly easier to tote around the world.

Smith remains underrated as a visual artist, and her skills are on display in the book — she leverages the form to create subtle or implied visual and/or thematic connections through her sequencing of the entries. The image for March 18, for example, features a teacup that displays “Mama,” a gift from her daughter, and a small photograph of Beverly that happens to be in the frame. The adjoining page, March 19, contains an image of a baby Patti being held upright by her mother. On September 6 and 7, an image of Smith’s boots and a stray sock appear opposite a tidy tableau of possessions ready to be packed, including multiple pairs of clean socks. It’s the kind of insistent yet subtle curation that Smith has practiced in all of her artistic channels. A Book of Days provides a striking experience for anyone casually flipping through the pages — with additional layers waiting for those readers who take the time to engage.