Quarantine culture began on March 11, when Whoopi Goldberg rattled out a greeting to a studio of empty chairs on the set of The View: “Well, hello, hello, hello! Welcome to The View, y’all. Welcome to The View! Welcome to The View! Welcome to The View! WELCOME TO THE VIEW! WELCOMETOTHEVIEW! WELCOMETOTHEVIEW.” That day, the reality of the coronavirus pandemic breached the walls of pop culture: Tom Hanks and Rita Wilson announced they had contracted COVID-19 and were self-isolating in Australia; Rudy Gobert of the Utah Jazz made light of social-distancing measures before testing positive too, forcing the NBA to suspend its season indefinitely. And the mad cherry on top? A clip from The Masked Singer — featuring former vice-presidential candidate Sarah Palin rapping “Baby Got Back” in costume as Bear while Nick Cannon booty-popped alongside her — went viral. Surreal, distressing, stupid. It made total sense.

The View was a step ahead of where the rest of New York — and most of the country — would end up. At the time, I was working on a profile of Celine Song, whose play Endlings was set to open at the New York Theatre Workshop. When it closed just days after it had opened, she texted me, “I’m a full widow.” Soon, the entire cultural life force of the city would be drained. There would be no more live studio audiences. No restaurants, no bars, no movie theaters, no plays, no concerts, no readings, no parties. Nothing.

But it would have been naïve to think culture had ended. It simply moved into the rabbit holes of the internet. Allegedly, events still happened in the real world, but the more privileged among us were locked inside with our guilt and fear and Wi-Fi. We were all extremely online, which felt like hotboxing off bad weed; our brains smoothed into little pearls. Quar brain and quar culture had commenced.

During the early days of the pandemic, Ling Ma’s 2018 novel, Severance, enjoyed a resurgence. In its fictional New York City, a fast-acting virus called Shen Fever tears through the world. The afflicted turn into zombies, only they aren’t the violent, teeth-gnashing variety. They’re victims of nostalgia. They perform an action from their past lives, like setting the table or reading a book, in an endless loop as they slowly rot away. One character returns to her childhood home only to succumb to the illness as she tries on her clothes, forever making pouty lips in the mirror.

The novel’s prescience comes from this understanding of human behavior. The etymology of the word nostalgia is a combination of the Greek algos, meaning “pain,” and nostos, meaning “homecoming.” As the pandemic grinds us down, it is the desire for the status quo — back to brunch, home for the holidays — that has threatened to place us in our own endless loop.

The entertainment world, too, made various attempts to return to normalcy. Super-producer Scott Rudin offered Broadway tickets at a discounted price of $50, calling it “an unprecedented opportunity.” Tom Cruise shot a video of himself going to see Christopher Nolan’s Tenet, which was funnier for his trademark blanket enthusiasm. (“Back to the movies!” he said without irony.) Despite his best efforts, Tenet lapsed into the ether. Most movie releases were delayed by a month, then pushed to the fall, until they fell off the 2020 calendar entirely.

TV writers’ rooms scrambled to adapt to the rapidly changing world order: Brooklyn Nine-Nine, a sitcom about lovable cops, ripped up its first four episodes in response to the Black Lives Matter protests; Grey’s Anatomy, Superstore, and Law & Order addressed the pandemic with varying degrees of success. They didn’t want to seem out of touch with the world, but they inherently are. TV shows are poor scribes of recent history — by the time they write, shoot, and edit an episode, the narrative has already shifted. As the pandemic stretched on, the best TV provided an escape hatch: Tiger King, Avatar: The Last Airbender, Love Is Blind, The Great British Bake Off, The Undoing. New content offered familiar comforts. Productions that tried to look at the pandemic too directly, either in form or in subject (Netflix’s Social Distance, HBO’s Coastal Elites), barely registered. Nobody wanted to watch a show to process our daily horrors.

➽This year, we’re recognizing the defining culture of our locked-down lives with the Quarries, our first (and hopefully last) quarantine awards. See our full list of winners.

Still, funny, challenging, inventive work was everywhere, if you knew where to go. The art that spoke to the feeling of 2020 didn’t attempt to look backward or forward; it channeled the hive mind of the internet. Creativity burst into Verzuz battles, Fortnite concerts, Animal Crossing world-building. Virtual reality was a reality freshly poured from someone’s brain onto your screen. The internet became more internet — an ever-thickening soup of private derangements and niche dramas.

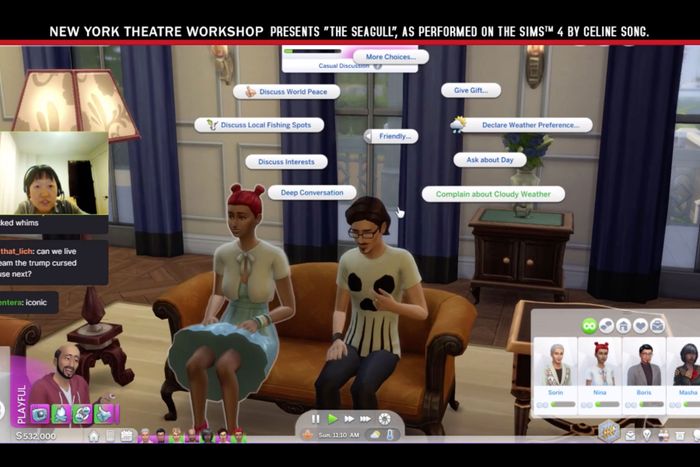

Playwrights produced some of the most formally innovative work: After the premature death of her own play, Song staged an interactive version of Chekhov’s The Seagull inside The Sims 4, somehow translating the angst of the text into code. Michael Breslin and Patrick Foley’s online theater production, Circle Jerk, was exhaustingly accurate in how it captured the neck-snapping frenzy of the internet. Comedian Ziwe Fumudoh’s Instagram Live series leveraged the intimacy of FaceTime by mastering the art of the uncomfortable close-up — but as with many of the most effective live events this year, part of the fun was the endless stream of responses from the commentariat. Things that would previously have been niche internet phenomena were now front and center: Leslie Jordan, best known for Will & Grace, created a series of Instagram videos that were more imaginative than anything that came out of Hollywood. He could just be funny.

During a moment of rupture, it was less the Hollywood executive who determined what people watched and more anyone with a phone (or, yikes, an algorithm). How better to explain the spectacular implosion of Quibi, a streaming service built for a medium its creators didn’t seem to grasp? The best thing Quibi gave us wasn’t on Quibi but on Twitter, where a viewer recorded himself watching an episode of the show 50 States of Fright. It stars Emmy winner Rachel Brosnahan as a woman dying of gold poisoning from her — wait for it — prosthetic golden arm. That you couldn’t watch Quibi on anything other than Quibi only highlighted the dissonance between executives and how content travels on the internet.

A similar miscalculation was made by Sarah Cooper’s Everything’s Fine — a dispiriting attempt to adapt her online shtick for a Netflix comedy special. Cooper became famous for taking a reliable internet formula and tweaking it for the boomer class by doing lip-syncs of Trump’s speeches. In Everything’s Fine, those same lip-syncs went limp upon arrival, deadened by a fattened production budget and celebrity actors. It lost its sense of immediacy, which meant it was already dated.

It was TikTok, the app Cooper made her name on, that became the most fertile storytelling medium of the pandemic — accomplishing what Quibi could not, which was to create bite-size entertainment people actually watched. In place of top-down decision-making, a more horizontal body — collaborative in an accidental and serendipitous way — appeared. TikToks went on Twitter, which went on Instagram. Memes coalesced into events, each one a wave to surf until the next came along: “My plans/2020”; “Is it cake?”; “How this email found me”; “What isn’t X but feels X?”

Perhaps because much of this content creation is free (and provides free labor for tech companies), memes haven’t achieved recognition as “art.” But over time, they have become increasingly sophisticated and insane, taking the form of video collages, lip-syncs, Photoshopped images, skits. Editing is king. Iteration is constant and delightful, as though a bunch of high-achieving students were attempting to elevate a meme toward its Platonic ideal. For instance: A user clips a moment of Raven-Symoné cackling to herself after an Instagram Live conversation. It goes viral.

Then someone shortens it and adds a background track from the “Lacrimosa” section of Mozart’s Requiem in D-Minor.

Here’s another: Kamala Harris’ “We did it, Joe” phone call to president-elect Biden — hilarious on its own — becomes a TikTok meme. The audio of the best recreation then gets looped back onto the original video.

Celebrity itself became a rich text to draw from — a lingua franca a reader could mold or interpret at will. Intention mattered less than interpretation; in fact, the greater the gap, the better. Gal Gadot thought we would all feel better if she and her rich friends sang an off-key cover of “Imagine.” (And you know what? We did.) Madonna made bizarre pronouncements from her bathtub. The real entertainment came afterward — in the flood of jokes and memes that surfaced.

Out of this constant churn came a broader view of the world and ourselves. This wasn’t “representation” in the basic sense; it was a feeling of recognition. There was a shorthand to a video like the one TikTok user @420doggface208 made while drinking Ocean Spray and lip-syncing to Fleetwood Mac’s “Dreams.” You could just relate.

The current moment echoes another. During World War I, a group of expat artists gathered at the Cabaret Voltaire in the neutral zone of Zurich, where they came up with an idea to match the mood: Dada. It would encompass everything and nothing — a laugh in the face of social collapse. Dada was deliberately infuriating as an anti-art art movement whose main goal was to stick a finger in the eye of the Establishment and swirl it around.

While Dada’s antipathy to the war was part of its animating origins, it took a more aggressive political turn when its center shifted from Zurich to Berlin. The ferocity and mania of the work reflected the collapse of Weimar Germany, which was beset by its own postwar humiliation and an anti-Semitic conspiracy theory: that Germany had never lost the war and that German Jews had forced the surrender. “We had lost confidence in our culture,” said Marcel Janco, a Romanian-born artist who went to Zurich at the onset of the war. “Everything had to be demolished … We began by shocking the bourgeois, demolishing his idea of art, attacking common sense, public opinion, education, institutions, museums, good taste, in short, the whole prevailing order.”

Formally, the Dadaists embraced chaos and nonsense. They favored collage and montage, whether through photography, typography, or sculpture; the collision of dissonant ideas and images was a way to jolt viewers out of their stupor. A common refrain was “Everybody can Dada.” In many ways, the internet has allowed for a realization of Dada without a centralized authority (which is so Dada). Just as it emerged from the bowels of World War I (and the 1918 influenza pandemic), you could see glimmers of a similarly absurdist sensibility reflecting the times — a Gen-Z/millennial cusp brand of disillusionment and anger. The coronavirus is the accelerant thrown on a fire that has long been burning: a for-profit news media, the erosion of our public institutions, a two-party political system made up of a white-supremacist death cult and corporate nostalgists.

As the disparity between common sense and governance has only widened, online culture has grown more disruptive. Memes increasingly have a subversive, combative edge to them — there are fewer niceties and no one is pulling their punches. (Hence, Copala memes.) There’s more shitposting, trolling, Warholian obscenity, and an unironic love for bad things. Various interests cross-pollinate: anime meets hip-hop meets cartoons meets porn. It’s not uncommon to see a beloved childhood character getting railed by a giant penis or an anime rendering of Megan McCain crying at her father’s funeral. All are part of the local parlance.

It’s hard not to read the current moment as a broader reaction to the deterioration of our social and political institutions. News headlines read like Mad Libs. Nonsense makes sense. Rome is burning while Nero is out golfing. Gal Gadot is singing the world a sincere lullaby, and Rudy Giuliani is yelling. The real legacy of comedy under Trump is not comedy about Trump but comedy that dislodges that same mania you feel whenever you see him speak. There’s a stench of fatalism in the air: Who cares? Everything is stupid, so let’s make stupid art.

*A version of this article appears in the December 7, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!