How do you know you’re dealing with one of the all-time great actors?

When they die, you don’t know where to start.

So I’ll repeat what Donald Sutherland’s son Kiefer said today when announcing his father’s death at 88: “I personally think he was one of the most important actors in the history of film.” Despite the first-person qualifier, this is as close to a statement of fact as you’ll find. Few actors were in as many artistically significant films all through their lives, decade after decade, or were as integral to the medium’s success and longevity. Few actors committed as ferociously to every role, large or small, labor of love or work for hire. Few actors were so damned much fun to watch.

Donald Sutherland was great and beloved. Talk to anyone who loves acting and ask them to name their favorite work by this man, and they’ll need a minute to think about it, and change their minds repeatedly. His performances in Ordinary People, Don’t Look Now, Klute, Six Degrees of Separation, the 1978 Invasion of the Body Snatchers, The Dirty Dozen, and M*A*S*H are so perfect and true that if any other actor had done even one of them, they might have been typecast as the character for the rest of their lives. Instead those parts stood alone, unique and apart from every other Sutherland role.

He clearly loved challenging, potentially alienating characters, especially in obsessive auteur projects that had a whiff of Ahab to them, like Fellini Casanova, 1900, and A Dry White Season. But he could also crush roles that might’ve seemed standard-issue on paper, like the blandly ruthless President Snow in the Hunger Games films (which may prove to be “gateway drug” performances for future Sutherland completists, as the Star Wars and Lord of the Rings movies were a way for people to learn about Christopher Lee). Well into Sutherland’s 70s and 80s, he continued to deliver richly detailed, often revelatory work, whether playing an Alzheimer’s-afflicted senior citizen in The Leisure Seeker or J. Paul Getty in the FX series Trust, a miserly monster who refused to pay his grandson’s kidnappers the ransom they demanded until they sent him a severed ear.

Sutherland’s instinct for the most honest way in to a moment was so keen that he that could even take an old Hollywood chestnut like “hard-ass coach who only wants the best from his athlete and secretly loves him like a son” and crack it open in a way that could turn even the most cynical filmgoer into a blubbering wreck. That was Without Limits, the funeral scene of which belongs in the Sports Movie Tear Gas Hall of Fame, alongside Gary Cooper as Lou Gehrig in The Pride of the Yankees telling the crowd he’s the luckiest man on the face of the Earth. When Sutherland gets up in front of the mourners, you feel like you’re watching not a sports drama with archetypal characters but a video of an ordinary man asked to speak at a memorial service. His performances as two grieving parents, in Ordinary People and Nicolas Roeg’s nonlinear horror drama Don’t Look Now, take viewers right into the heart of that specific kind of pain, which is characterized by a combination of traumatized numbness and a desperate reaching out for familiar comforts: a chance to cheer the home team at a high-school swim meet, a too-quiet family dinner that ignores the fact that someone’s not there, an anxious and needy tryst.

He seemed special from the moment he broke through in the late 1960s. After many years of paying his dues onstage and on TV in Canada, he acted in a string of counterculture-attuned war films, including The Dirty Dozen, Kelly’s Heroes, and M*A*S*H. Then he moved on to leading-man status in the likes of Klute, Don’t Look Now, Steelyard Blues, Casanova, and the 1978 remake of Invasion of the Body Snatchers (origin point for one of the single greatest images in horror-film history: Sutherland pointing and screaming, now an inescapable meme). Starting in that decade and continuing throughout his life, Sutherland cemented his status as one of those actors you were always glad to see, especially when you didn’t know he was even in a film.

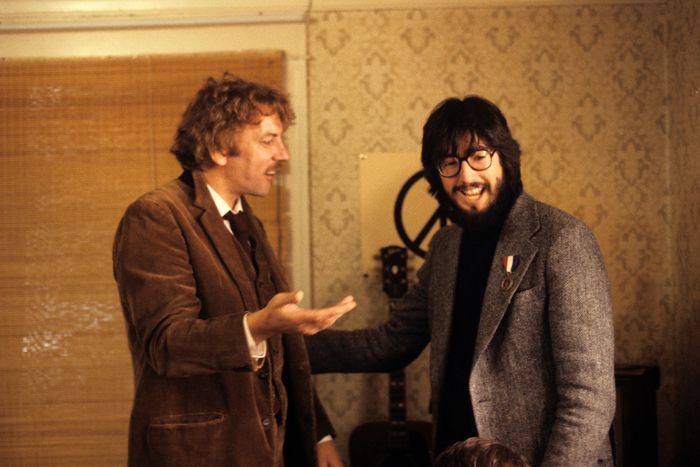

He was a bohemian, hedonistic leftist who made FTW, an anti-Vietnam War documentary with Jane Fonda, and was put on a CIA watch list for his political activities. He never entirely abandoned the just-hitchhiked-in-from-the-commune, mustachioed-brother-of–Tom Baker–in–Dr. Who look. In a 2017 profile on 60 Minutes, he said he’d tanked his first movie audition because, according to the producers, the part was for “a guy-next-door sort of guy, and to be absolutely truthful, we don’t think you look like you ever lived next door to anybody.” Sutherland was instead at home playing weirdos, like the anachronistic proto-flower child in the World War II movie Kelly’s Heroes, the Hannibal Lecter–ish arsonist in Backdraft, or the preening reverend in Little Murders who turns what should be a simple marriage ceremony into a navel-gazing monologue that’s the pre-internet version of a TED Talk. (The latter two roles are examples of a Sutherland specialty: the high-impact cameo that tucks a whole movie into an actor’s back pocket. The greatest example is his 16-minute appearance in JFK as Mr. X, the informant who lays out the conspiracy for Kevin Costner’s fretful hero, ending with a jocular, “The truth is on your side, Bubba!”)

You could also make a case for Sutherland as one of the best examples of a legendary actor who accepts larky, off-brand small roles, or bigger roles in franchise films that others might treat as a savings-account fattener, then acts them with such integrity that you’d think he’d gone on set thinking it would be the last part he’d ever play. Besides his short-duration, deep-impact work in JFK, Backdraft, and Little Murders, consider his slapstick performance in just one shot of The Kentucky Fried Movie, in a trailer for a nonexistent disaster film called That’s Armageddon!; his silent, entirely physical performance as the tormented psychologist and would-be weather-machine technologist Wilhelm Reich in the music video for Kate Bush’s “Cloudbusting”; or for that matter, his voice role on The Simpsons as Hollis Hurlbut, the head of the Springfield Historical Society in “Lisa the Iconoclast,” in which he takes what might otherwise have been a lightly ironic farce about a historian learning the truth behind a legend and turns it into the quietly heartbreaking story of a man processing the revelation that he built his professional identity on a lie, then moving on from it. Even Sutherland’s voice-overs for products were masterclasses in believing the fiction. A 2008 ad for Simply Orange Orange Juice becomes the pitchman’s version of a sonnet.

He was personally responsible for one of the most piercing scenes in Ordinary People, where Mary Tyler Moore’s icy, numb Beth comes downstairs in the middle of the night and finds her husband, Calvin, sitting at the dinner table, where he confesses, “I don’t know if I love you anymore.” Sutherland originally played the scene with Calvin disintegrating into sobs. A few days later, they watched the rushes, and Sutherland asked if they could reshoot the scene because he worried he’d “fucked it” by showing too much emotion. Redford said no, then changed his mind three months after production had wrapped. By that point, they couldn’t get the cinematographer, John Bailey, and Moore was off doing a play. “He told me that he could get Robert Surtees [who shot The Graduate] to film it and while he didn’t have the set, he did have the curtains and a window. ‘I’d have to play Mary’s part … would you mind doing it again?’ So we reshot it. That’s me acting against Bob Redford there.”

He was, quite simply, one of the best ever to do it. But at the same time, paradoxically, he was one of the least widely recognized for his consistent greatness, at least by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, which hands out Oscars. Sutherland finally got an honorary statuette in 2017 for lifetime achievement, 55 years into his acting career, after never being nominated even once in regular competition. Why? Maybe it was because Sutherland had a rare ability to be dashing or assertive and otherwise make audiences feel they were in the presence of a true and thrilling leading man — some kind of movie star — while at the same time making you believe you were just watching an uninflected record of a guy doing what that specific guy would definitely do.

Often Sutherland was as good as whichever other actor from the same film had been nominated for an Oscar, and who might not have gotten nominated without Sutherland providing such sturdy support. Consider Ordinary People, the Best Picture winner for 1980. It got six nominations, including Best Picture and Director (Robert Redford), Best Adapted Screenplay (Alvin Sargent), Best Actress for Mary Tyler Moore, and Best Supporting Actor for both Timothy Hutton and Judd Hirsch (Hutton won). Nothing for Sutherland. On Entertainment Weekly’s list of the 25 worst Oscar snubs for acting, this one came in at No. 15. You could call it blatant injustice. Or you could say that Sutherland’s greater reward was knowing how extraordinary he was all the way through, so good that people would continue to complain about his non-nomination for the rest of his life (and beyond).

In quite a few years, his not-nominated performances were as good as or better than whatever won. One film I’d put in that category is Six Degrees of Separation, the Australian director Fred Schepisi’s dazzling, nonlinear 1993 adaptation of John Guare’s play, starring Sutherland and Stockard Channing as hotshot art dealer Paul Kittridge and his socialite wife, Ouisa, and Will Smith as Paul, the brilliant, earnest, secretly gay hustler who charms his way into the Kittridges’ townhouse. Channing deservedly got nominated for Best Actress, but it was Sutherland as the husband (again!) holding the film aloft like a tweedy Atlas, dazzling in monologues about art and heartbreaking in admissions of gullibility and emptiness. Here, as in so many other classic Sutherland performances, he surprises you with information that, in retrospect, you should’ve seen coming, as when Paul and Ouisa quietly and not too subtly begin airing their fundamental conflicts during an important dinner. The film cuts to the couple fighting in the courtyard outside, and when Paul realizes his voice has risen to an embarrassing volume, he falls silent. He gives Ouisa a look that makes you anticipate a reflexive apology, then shockingly says, in a cold, guttural voice, “I am a gambler.”

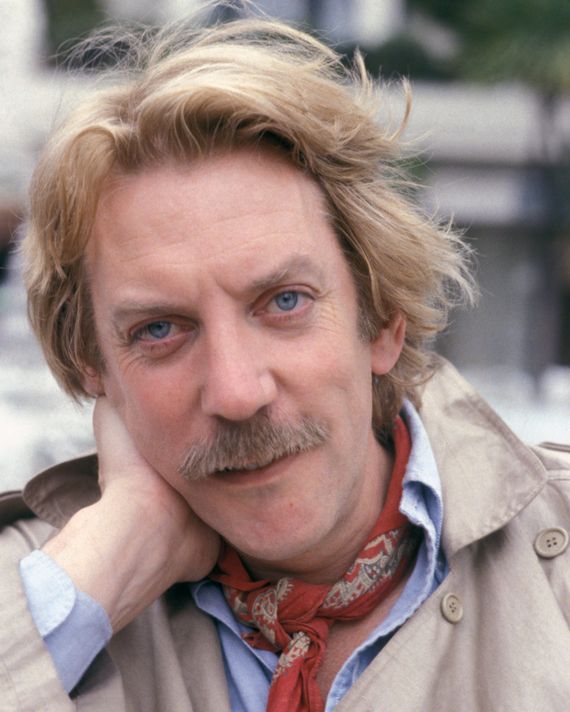

Sutherland was also, it should be said, sexy as hell, in that “What, really? Him?” way that a lot of the hottest ’70s leading men were hot. He told an interviewer that when he was a boy, he asked his mother, “Am I good looking?” She looked at him for a bit “and said finally, ‘Your face has got character.’ I was in depression for a year.” Enough moviegoers disagreed to make Sutherland one of the greatest oddball leading-man crushes in cinema. It wasn’t just Sutherland’s tall, lean frame, gregarious energy, and convincing performances as smart guys that made him attractive. (Remember his caddish professor in Animal House?) It was the way he looked at his leading ladies: mesmerized, moonstruck. It sometimes seemed like he played things flirty even when the part wasn’t necessarily written that way. There’s often an aspect of “is he or isn’t he” (i.e., in love) to Sutherland’s leading-man roles. In Philip Kaufman’s 1978 remake of Invasion of the Body Snatchers, he plays a San Francisco health inspector named Matthew who draws his unhappily married co-worker Elizabeth (Brooke Adams) into a sci-fi conspiracy. Early in the movie, there are a pair of scenes that almost make you wish you were watching these two characters in a regular romantic comedy. Adams and Sutherland believably play their characters like people who, deep down, are in love with each other but haven’t quite recognized what’s happening. Sutherland amps up this sensibility by playing every scene with Adams as physically close as he can get without seeming to invade her space. He keeps doing little physical things that read as auditioning-boyfriend behavior but are plausibly deniable as such, like handing Beth a bottle containing a rat turd he found in a stewpot at a restaurant (this movie’s version of a gentleman handing a lady a flower) and then, after he’s reclaimed it, gently holding her hands for a second, and smiling as he speaks to her.

Sutherland was an icon who didn’t announce himself as such — as distinctive as any actor that people try to impersonate, yet impossible to imitate because everything about him seemed spontaneous and authentic, from his look and sound to his energy and presentation. It’s impossible to read quotes from Donald Sutherland without hearing his honeyed bourbon voice saying them. It’s impossible to watch videos of him talking about his craft without waiting for the inevitable moments when he takes the piss out of a deep question with a joke. (When the critic Mark Cousins showed him the famous sex scene between him and Julie Christie in Don’t Look Now and asked if he “looked back” nostalgically while watching it, he replied that his first thought was, Oh, the wig looks good.) You can’t look at any photo of Sutherland from any stage of his career without thinking about what an amazing beauty he had, with those haunted French-philosopher eyes; that sharp, narrow face; the slightly off-kilter way he held himself because of the way polio damaged his body as a child; and the bold, maybe heedless grooming choices that time-stamped him in the 1970s and that he continued to embrace even late in life, when he cultivated a professor-emeritus-of-painting vibe, shoulder-length hair swept back and tucked behind his ears. He was so completely himself offscreen that you felt as though you knew him, and so unpredictable onscreen that you could never guess where he was going.