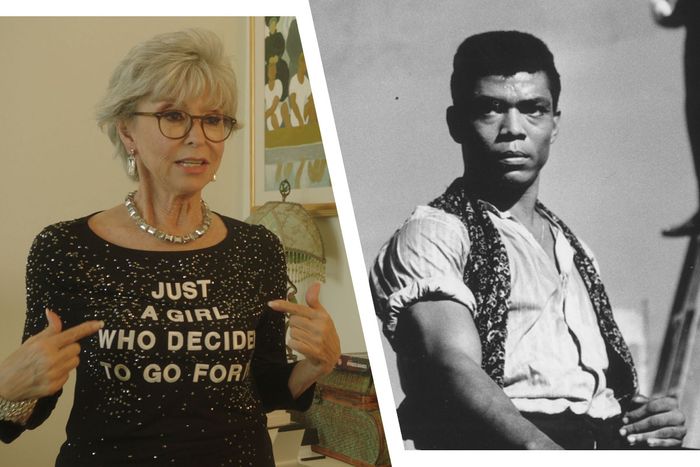

This year’s Tribeca Film Festival includes two documentaries about truly legendary performers. In many ways, the films echo each other: They’re both about children of the Depression, artists whose struggles against racial oppression made them “firsts” in their fields, artists who have won both the Presidential Medal of Freedom and are Kennedy Center Honorees. The films themselves shine like medals around the artists’ necks: Love — or worship — sits at the core of each project. (These are deferential, at times often promotional documents.) But Jamila Wignot’s Ailey and Mariem Pérez Riera’s Rita Moreno: Just a Girl Who Decided to Go for It are alike in another way too. They both demonstrate the limitations of trying to explicate genius. Talking heads can honor Alvin Ailey’s choreography; they can pay tribute to Rita Moreno’s spirit of tungsten steel. But neither documentary can really draw us inside its object — Ailey because the man himself is gone (and hard to know when he lived); Rita because her stories have already been polished to a high diamond shine.

Ailey is the more formally ambitious film — less practically useful (a harum-scarum approach to chronology can be bewildering) but more successful at creating sudden dazzlements. These shimmers are almost always clips of Ailey dances: Wignot touches archival footage like jewels, sometimes returning to a sequence so that we can see its facets in another light. The rare stuff is particularly precious, like a black-and-white film of Lester Horton’s vertigo-inducing Dedication to José Clemente Orozco, which Ailey danced with Carmen de Lavallade. But even the much-handled treasures haven’t tarnished. Ailey returns frequently to the dominating masterwork of his life, Revelations, which premiered in 1960 and is still a blockbuster more than 30 years after his death. A thousand productions have not made it grow old.

Wignot builds her documentary within the context of another effort to capture Ailey’s life: the hip-hop choreographer Rennie Harris’s 2018 commission Lazarus, which he devised for the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. The film’s contemporary scenes take place at Ailey’s gleaming campus in Manhattan, where we see Harris setting movement on the company dancers. He, like Wignot, pores over films in the archive, since there seem to be no friends other than former employees to interview, no diaries or letters available that can crack open the choreographer’s deep privacy. Instead, Harris, like Wignot, seizes on Ailey’s phrase “blood memory” as a key to his mysteries, patching the fragile record with other people’s pain when necessary. Wignot uses stock footage to evoke the Texas Ailey was born into; Harris includes images that were not part of Alvin Ailey’s past — young men dangling as if from nooses, for example. Neither one gets far when confined to literal biography, so they work laterally, sending their works into reverie or shared Black trauma instead.

Between these shots of Harris’s rehearsals, Wignot unspools long sections of Ailey’s life story, much of it narrated by pieced-together old interviews. Since we rely on him as our guide, when Ailey is vague, the film is vague too — what happened to his lover who disappeared down a fire escape? When and why did Ailey stop dancing? What was it like to be sent on state-sponsored tours through the Soviet Union, threatened by the FBI not to show any “effeminate” tendencies? The first question arises but is never answered; the last one isn’t even broached. Via Ailey’s recorded voice and his living colleagues, we hear mainly about a climb toward glory and then enough hints about AIDS to make a tragedy — we linger on images of him gaunt and frail, kissing Nancy Reagan’s cheek at the Kennedy Center Awards before his death in 1989. Alone of all the witnesses consulted, only Bill T. Jones speaks tartly about Ailey’s own avoidances and erasures in that journey. “Where was his gay community?” he asks, still stern, still disappointed in Ailey’s silence about the disease that killed him and clear-eyed about the way the white establishment used him for their own purposes.

Rita Moreno, on the other hand, is delighted to break her silence. Riera’s documentary seems to pick up mid-anecdote — there’s little evidence Moreno ever gives silence a fighting chance. At 89 (87 at the time of filming), she has found a second (third? fourth?) stardom with the television reboot of One Day at a Time, and she stretches in that spotlight like a cat in the sun. In fact, all attention makes her purr. Laughing, she frames her feminist activism as part of her hunger for the limelight, and when she recalls old affairs, she doesn’t dwell on the love she had for the men (like, say, her on-off boyfriend Marlon Brando) — she marvels instead at how much they loved her. Near the end of the film, she sees a street mural of her face, and she runs up and embraces the wall. Look, you want to vibrate like a lightning bolt at this age? You need a healthy ego.

Moreno’s constant, ebullient pleasure in life (we see her find the blintzes at craft services and it is a celebration) does defy the ugliness of the world that made her a star. American culture’s on-off love is complicated — she has won the EGOT (Emmy, Grammy, Oscar, Tony), but that industry adulation has come at a cost. Roles traduced her Puerto Rican heritage, asked her to paint herself brown, to play the feisty lover or the Burmese maiden or the pouting firecracker. The first section of her career, when she was a young starlet under contract to MGM, was both infinitely glamorous and endlessly humiliating and vile. Her agent raped her, she says, matter-of-factly, and she didn’t even fire him.

Despite her forthrightness about her experiences, we don’t get much of a sense of her artistic secret or what makes her such a strong performer. In the film’s central interview, she talks about her disappointment with the racist caricatures foisted on her younger self; she speaks adoringly of playing West Side Story’s Anita, a bold fiction she says became — in the desert of Hollywood — her only role model. She only offers hints at what makes up her craft. A picture showing her rehearsing Anita’s dance points to her perfectionism; a moment at her makeup table indicates something about the power of her own self-regard. She finds herself magnetic, which then turns every eye. It helps that she’s starstruck by herself.

Riera’s documentary — produced by Norman Lear and Lin-Manuel Miranda — is itself a little starstruck. It includes several interviews with those who look up to Moreno as a Latina trailblazer (Gloria Estefan, Karen Olivo) and testimonials from co-stars (Hector Elizondo, Morgan Freeman), who say blandly positive things. These tend to cover the same ground, and many fail to add any dimension to her portrait. More provocative are the contributions from media scholars, who pose questions about what could have been had Hollywood been different — less bigoted, less sexist, more willing to write roles worthy of her talent.

It’s worth asking about what could have been. Both Rita Moreno and Alvin Ailey were born in 1931. They are, or were, exact contemporaries. Watching the documentaries back to back, you cannot help but wonder: What if Moreno’s 1960s had been like Ailey’s, full of aesthetic innovation instead of studio-dictated convention? And for that matter, what if Ailey had lived to a late, Moreno-ish Renaissance in the 2010s? They have both done so much, it’s greedy to ask for more. But while both documentaries are records of staggering achievement, they are also evidence of a theft. An unjust world stole her youth and his old age — and it will not give them back.