You’ll find no comfort in exotica here. No kaleidoscopic weddings to reel a reader in. No stern fathers, no dishes to remind an exile of home, no careful arranging of marriages. In The Immortal King Rao, the first novel by Vauhini Vara, the tune sounds different from the others that seem to bind Indian diasporic literature. There are, however, a lot of coconuts — and at least one mango. The coconuts belong to a discordant, bloody family farm in South India; later, Coconut will become the name of the tech company that the family’s prodigal son will develop once he lands in America, before going on to sort of rule the world. The most notable mango-eating scene directly precedes a gory murder.

Vara, a longtime tech journalist and an editor who has worked at The New Yorker and The Wall Street Journal, sings a song all her own in a premonitory, daring book that lands somewhere between speculative fiction and bildungsroman, storytelling and fortune-telling. The rise of its hero, King Rao, helps define a time in the near future when inhabitants of America largely identify as Shareholders; Rao started the company that controls their lives, the blown-out Apple analogue Coconut. By the time of the book’s present day, King has been ousted from the company by an all-powerful board. Those seeking escape from the tyranny of an information- (and consciousness-) sharing economy, known as the Exes, have absconded to a set of islands off the coast of Washington State that they call the Blanklands. These outliers are willing to sacrifice comfort for freedom from the protection and possession of their lives by a morally fraught company, and they live together in tenuous harmony. Meanwhile, the target of their ire — Rao himself — lives in secret nearby with his daughter, Athena, with a trail of casualties behind him for her to discover. It’s Athena who tells us the story.

The novel flashes through time and space with an agile clarity from before King’s birth to grown-up Athena’s present day. Yet Vara has not exactly made this book an easy read. King is Dalit, a member of the so-called “untouchable” caste, whose parents have adopted the high-caste family name Rao. In one critical scene from King’s childhood, he is confronted by a one-legged man who lives near the family’s compound. “If you’re a person like us — a cripple, an untouchable — you’ve got to make them afraid of you. You’ve got to place yourself above them however you can,” the man tells King. Then he insists the boy touch the stump of his severed leg. “Go on, rub it,” he says, and King does; the man closes his eyes and sighs, murmuring, “Good, good.” Vara tells us the stump is “smooth, hard, hot.” King begs to stop.

King feels ill at that moment. I had felt ill myself, during earlier scenes. Indeed, I found the novel unbearable at times — whether during the bloodbath that signals King’s birth or while witnessing moments between a widowed King and his daughter that seem more marital than parental in spirit, as when King accidentally glimpses Athena’s naked adolescent body. In this particular passage, however, between King and the one-legged man, I saw a logic in the book’s methods. Vara does not emphasize the photogenic side of life. In her ruthless depiction of the handicapped man — of so many lives in and around the plantation — she uncovers what can seem to be a vestigial Indian landscape of beggars, poverty, and birth defects, untouched by the new rights movements that has begun to wash the film of taboo from lives outside the mainstream. At other points, when writing about America, Vara depicts tech not as an organizing force able to smooth the edges and turn any reality bougie so much as a Sauron-like catastrophic power. The suburban bohemia that can seem to define the American novel is nowhere to be found here. The only community is a fractured one. The sharpest description of food is spent on a can of old, crumbly beets scavenged from a Blanklands tent. Vara, throughout, essentially asks the reader — forces us — to engage with the hidden parts, to rub the stump.

Perhaps it makes sense that some of the most trenchant work on the shortcomings of technotopia is written by women. Outnumbered in the industry, women drawn to the tech ecosystem can find an outsider’s position from which to make sense of its overlords — those “ambitious, aggressive, arrogant young men from America’s soft suburbs,” as Anna Wiener puts it in her memoir about her time in start-up land, Uncanny Valley. Wiener was inspired in part by the writings of Ellen Ullman, the programmer-cum-writer whose dazzling 1997 memoir, Close to the Machine, probes the links between masculinity, coding, and techno-futurism. As Ullman put it to Wiener in a 2016 interview, the goal of tech may well be to change the world, but for whom? And to what end? Ullman thought everyone should know that “programs are written by people with particular values — those in the clubhouse — and, since programs are human products, the values inherent in code can be changed.”

In The Immortal King Rao, Vara constructs a world designed by man and woman. While King may be the public face of the company, it is really his wife, Margaret, who’s driving. Moreover, the idea for the company’s most radical creation — a consciousness-uploading device called the Harmonica — is stolen in part from a paper written by a female programmer at a rival company. King names lofty purposes: By allowing people to communicate online simply by thinking, he’s opening up possibilities for people who can’t speak — for instance, his own father. He’s also abetting the creation of a record of human existence, the only trace that might remain after climate change destroys the earth. Of course, he has other agendas, too, like the expansion of his own empire and, in a sense, his life. Unbeknownst to Athena, he uses the Harmonica technology to connect his daughter’s mind to his own, in the ultimate bad-parent move, turning her life into a vehicle for prolonging his. (And offers up a useful storytelling hack; Athena narrates King’s life via access to his memories.) Yet King is a complex figure, neither villain nor hero. “King Rao might have started all this,” says Elemen Ex, a rebel who takes Athena under her wing. “But if he hadn’t done it, someone else would have … If we had killed him, someone else would have become CEO in his place.”

Although Elemen Ex’s description paints King as interchangeable, the character’s identity is part of why the story is so notable. Like King, Vara is of Dalit heritage herself, and she drew on her own family history to build the setting of the coconut plantation. In an email, Vara told me she that she doesn’t know of any other Dalit novelists in the US. She is an outlier. Her work, so focused on those who would be outliers too — the Zuckerbergs, the Bezoses — is doubly symbolic. By tracing the intricacies of a fictional Dalit family, she shines a light on a part of India and a psychography not often explored. Although the Hindu caste system exists most formally in India, it also pervades the West, imported through the terms of immigration; most early Indian immigrants to the US needed to prove they were “skilled workers” with a high level of education to obtain visas. Western public intellectuals of Hindu parentage are more likely to be Brahman, and the names give it away. (My own, for example: My family name is Rao, the Brahman pseudonym adopted by King’s family.)

Here is a truly American novel: Steve Jobs, but untouchable. Elon Musk, but brown. It can seem like too neat an idea, but in Vara’s hands, the invisible grottoes of the planet come alive. We see the bunk bed in a broken-down Indian shack as well as the elaborate hideout of a tech-mogul couple, landscaped with tropical plants tweaked by geneticists to thrive in Seattle. Some of the most compelling of the novel’s passages betray a journalist’s sense of the world. At one point, a music video designed to destroy King’s reputation goes viral in a believable, trippy manner, with Vara’s language conjuring a kind of Black Mirror montage. In another deep aside, she introduces a photographer who takes advantage of strung-out models; he sounds all too real, his exploits smacking of the stories the model Emily Ratajkowski recounted in her memoir.

But the internet of Immortal King Rao is also one mapped by a poet. Vara is forever aware of the costs of technology, of the hidden world behind the public one. This world teems with small moments — the cadence of romance, the missteps of an immigrant. Although the title character is a man, women are chief among the storytellers and meaning-makers. There’s the narrator, Athena. There’s the Rebel Elemen Ex, with whom Athena shares an uncanny connection. And then there’s the daunting presence of Athena’s white American mother, Margaret, whom King admits to himself is the rightful creator of Coconut. Margaret wants nothing to do with childbirth, with motherhood. She uses King — he’s pliant — because she knows the world will not accept her force. She’s a puppet master, but she loves him. We are rarely in a press conference with the couple; more often, we’re with them in the privacy of an office or a bedroom, aware of the tint of her skin and the heat of his breath.

Vara’s novel works in gyroscopic ways, world-building in a circular progression. Athena is her father’s daughter, as we are consistently reminded: When she eventually leaves him behind, it’s because she has dreams of her own, as he once did. By the time we arrive at the sharpest scene in which she accesses her father’s memories, we know enough to experience the happening through this double lens. Every child is arguably forever in touch with the parent of the past. But thanks to Coconut’s technology, Athena can plunge into a vignette from her father’s memory with a jarring and visceral intensity; she nearly becomes him. Afterward, she reflects on the feeling the scene leaves her with. She realizes she loves her father despite herself. She feels protective toward him, guilty about her need to escape, even as she recoils from the texture of his memories and his manipulation of her mind.

Vara is something of an old hand at this marriage of form and function. Last summer, she published a story in The Believer titled “Ghosts.” Part of it she wrote, and part she constructed: The essay, about the actual death of her sister, was written partially by an AI. Grief can render a griever mute. Vara found a way to tell the story through the filling-in capabilities of a sophisticated writing bot called GPT-3. It’s now possible for an algorithm to simply make up memories for you, give words to feelings you may as well call your own. The piece is surprising; it reads so alive. In her guidance of the AI, in her admission of her own inability to write about her sister, Vara somehow captured a human pulse — the beat of one person’s blood against another’s that constitutes love.

The Immortal King Rao too thrums with a pulse. The beating heart feels located in the love between daughter and father, a love that made me uncomfortable when I first encountered it. Born in unusual circumstances, Athena faces an age-old conundrum writ large. How do you break off from the larger-than-life parent? If King Rao must die, it’s for the old Greek reasons: to clear the path for his progeny, to make the story continue.

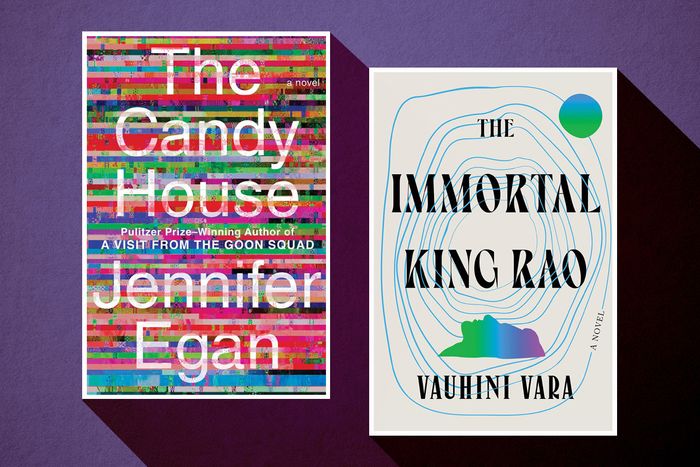

In Jennifer Egan’s novel The Candy House, a world that can seem twinned to Vara’s unfurls. Towering over it all is a piece of technology called Own Your Unconscious, invented by a man named Bix Bouton. In this case, interested parties can upload their unconscious — all their memories and thoughts generated up until the point of upload — to a cloud server. If uploaders choose to make this data available to anyone, they in turn will gain access to the data of others. Egan’s Bix, like Vara’s King, carries a seemingly magnanimous purpose in mind: He envisions the memory log as a way to bring family members together, a kind of digital connective tissue. Once more, a small ragtag group of defectors rails against this glossy argument; here, the rebels are called “eluders,” described by one character as “that invisible army of data defiers.” And once more, memories act as currency: They can be uploaded and accessed, mined for data, and used by loved ones for emotional and material needs.

The Candy House is dizzying, in scope and achievement. Egan telescopes in on more than a dozen characters with an unnerving mastery. Her new book is a sort of sibling to her Pulitzer-winning A Visit From the Goon Squad; old characters resurface, all grown up, and new ones populate their orbit. The rakish record executive Lou Kline is seen through the eyes of his daughters. Sasha Blake has traded her kleptomania for a quiet, celebrated life as a sculptor in the desert. To read Egan’s book alongside Vara’s is to witness a novelist in peak form next to one beginning her career, both using futuristic conceits to amp up old conundrums. (And to be struck by novelistic trends: The names Athena and Hollander appear in both books.)

At times, Egan’s approach feels almost too masterful. Rather than assert its contours organically through the course of character development, racial identity reads like just another tool in her arsenal. A minor character who breaks up a marriage is referred to as “the beautiful Asian woman who often sat with us at dinner,” as if the Asian part connects to the seductress angle. Egan’s tech titan, Bix, is a Black man, a detail that can seem chosen mostly for the purposes of justice and plot. When he dares to pose as someone much younger in one striking opening scene, he reasons that he tends to look younger than white people anyhow. His in-laws, white folks from Texas, once shunned him because of his race; now, his mother-in-law embraces him, a turn that seems painstakingly conceived. It’s as if Bix represents a kind of brokered, symbolic harmony: a Black man who is also the most powerful figure in this universe, unflappable and savvy, a transcender of race who telegraphs its importance. Not that anything feels forced, exactly. Egan moves her players around in exhilarating ways. Each section deals with a different set of characters — often an entire family — yet features subtle incursions from others who claim space elsewhere in the book. This, then, is a community rendered on the page, a group of folks who are somehow each the main character.

Bix’s inventions may provide the through-line, but for Egan, techno-reality is resolutely secondary to the miracle of existence, of skin-to-skin living. A beach glitters as two daughters run into the water with their absentee dad, the first real happy day they spend with him. Two overly analytical data analysts known as “counters” fall in love on a bed; he counts the pace of her heartbeat. Each section can seem to threaten despair, only to wind up on notes of quietly soaring, richly orchestrated positivity. A suicide attempt is thwarted, leading to a redemption arc we learn about from brief asides later in the book. Two warring, paranoid neighbors form a delicate friendship in the background of other stories. Egan’s brilliance at constructing vignettes is layered into more dimensionality here, thanks to the futuristic window dressing. But ultimately these are old, small tales. People are born, fall in love, marry, have children, die. The technology adds a layer of possibility, of complication: Characters can now see what a parent saw. They can see what happened on that day long ago when a friend died. Perhaps they can see life as a novelist does.

Where Vara’s book takes us into the root system — a tangled, dark, muddy place — Egan can seem to have her eye trained on the lotus above the water, lavishly attending to each petal, even as we contend with the somewhat nightmarish vision of a corporatized collective consciousness. There are so many moments in The Candy House that live in the realm of air, of grass, of blood. “How can the love and dread she feels for her middle son be converted into something tangible, something that can help him?” wonders the mother of Ames Hollander in a finely wrought final chapter titled “Middle Son.” It’s notable that Egan thanks her own sons in the acknowledgments; some of the book’s most affecting “love scenes,” as it were, occur between mother and son. Another observation in “Middle Son” rings eternal: “One horror of motherhood lies in the moments when she can see both the exquisiteness of her child and his utter inconsequence to others. There are so many boys in the world. From a distance they look alike even to her, especially in uniform.” Horror here ties to human quandaries, not ones invented by technocrats.

Social injustices are dealt with poetically, even playfully. And once again, women play shadowy, critical roles: Bouton builds his technology using principles outlined by an academic named Miranda Kline. The sequence of the novel that narrates Kline’s fevered departure into a life of the mind is one of the book’s most startling. She escapes her marriage and daughters to retreat to the jungle, where she performs esoteric, obtuse research that seems to hold meaning only to her. When she returns, she dives once more into a world of her own, writing in private and reverting to the clothing, appearance, and lifestyle of a student, which she becomes. Her behavior is incomprehensible to those around her. She looks very much like a bad mother, a bad wife. The slim volumes she produces go on to change the world — in ways, we come to understand, that she would not have approved of, as Kline becomes an eluder. She sought to understand what brought humans together; her decision seems to assert that tech connectivity does nothing of the sort.

Egan presents a world that looks somehow the same as it always has, no matter the state of technology. Vara’s view of a similar future reads punkier, darker, dystopic in a way that can make it hard to turn the page. For some people, of course, things really don’t change, no matter the conditions of the world. Egan’s book is arguably populated by such folk, who are born into a kind of security; Vara’s, not so much. Both authors offer the suggestive existence of rebels. Egan never shows us her eluders, though; we never go with them into the wilderness. Instead, we remain inside the Candy House of fairy-tale lore, a beautifully constructed novel where the human capacity to feel and touch persists. Perhaps it’s a trap that feels like protection.