White supremacy still finds purchase in these United States, and given enough oxygen, it will always come roaring back. This is the most pronounced idea in the fourth season of Slow Burn, which centers on David Duke’s rise in the late ’80s and early ’90s, when the former Klansman was elected to the Louisiana state legislature and went on to mount serious runs for governor and the U.S. Senate.

Reported and hosted by Slate national editor Josh Levin, a Louisiana native who grew up watching the Duke phenomenon, this season of Slow Burn is a scorching listen. At first, it feels reminiscent of a conventional study of how a politician assembled his base and worked to broaden his coalition. But, of course, Duke is no conventional politician. He is an embodiment of evil who sought to tidy up and nearly succeeded in gaining considerable political power.

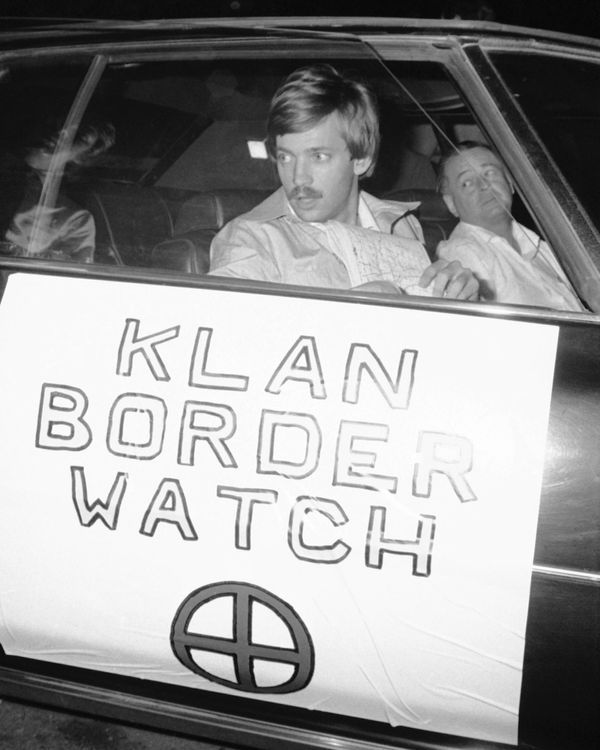

During his most active era, Duke’s fundamental project was an effort to make racism acceptable (again) or at least sneak it in through the back door, according to Levin. There’s a distinct uncanniness to Duke even as he becomes mildly successful in his rebranding effort, and part of what makes Levin’s storytelling particularly compelling is how he emphasizes that uncanniness. Levin describes a visually youthful Duke who even gets facial surgery, disguising the ghoul underneath. (Duke has said the procedure was medically necessary.) He is capable of remarkable charm one moment before quickly transforming into a snarling demon. He is a volatile figure, rich with the danger of uncertainty.

Duke’s repositioning allowed him to slither through the formal political system as an anti-tax Republican. The first three episodes focus on Duke’s winning some of those early battles, and Levin largely frames those instances from the perspective of those who lost: an Establishment Republican stalwart Duke defeated to gain his first important political victory in 1989, a member of Louisiana’s Republican State Central Committee who tried to expose Duke and push him out of the party, and so on. Woven together, these early stories collectively make up a portrait of a failed “Never Duke” resistance.

This is where parallels could be drawn between Duke and Donald Trump, especially in their respective political arcs and what they stand for. There are big differences, obviously. One is a former Klan leader with a coherent ideology; the other is a racist opportunist who found political utility in white supremacists. Duke ran for office several more times after the era examined in Slow Burn, including a 2016 campaign for the U.S. Senate, obtaining a meager percentage of the electorate each time. Trump, of course, found himself elected president in 2016.

Duke is alive and tweeting, and though he may have been pushed out of the conventional political arena, the same can’t be said for his ideology. In eastern Washington, State Representative Matt Shea forwarded an email from a group training young men in “biblical warfare,” and he was found to have participated in “domestic terrorism” in a report comissioned by the Washington State house of representatives. Meanwhile, President Trump recently retweeted (and later deleted) a video that contains a supporter yelling “White Power!”

All of which points to the grave reality that the problem of white supremacy will persist in this country. The former Klansman does not represent a meteor narrowly missing Earth, nor the current president a national anomaly, but a core aspect of the nation’s psyche that needs to be managed with constant vigilance.

*This article appears in the July 6, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!