This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

My life as a stage mom, or at least a stage mom in training, began in the fall of 2022, when my then-7-year-old daughter, June, was mesmerized by a production of Into the Woods on Broadway. Or it might have been the summer before, when her cousin taught her the words to “Dear Theodosia” from Hamilton and they spent weeks singing the song everywhere we went: outdoors and indoors, walking down the street, in the back seat of cars, on a crowded train with headphones on. But the point of no return came in January 2023, when Instagram’s advertising algorithm triangulated my interests, sensed my vulnerability, and fed me an ad for an organization called A Class Act NY, urging me to audition my daughter for a production of something called Into the Woods Jr.

The first time this ad appeared, I was on the subway, heading somewhere I can’t recall. I had not yet been introduced to the network of theater programs — the long list of Jr. shows — that offer children a chance to sing and dance onstage. I knew nothing about voice lessons, acting coaches, or talent showcases. I had never encountered a folding blue screen or wondered who voices JJ on Cocomelon (it’s a very talented kid named Cody Braverman). It was almost an afterthought when I asked June if she would like to audition, and when she said “yes,” I took a page from my own mother and warned her that the competition might be steep. She might end up playing a tree.

Childhood in New York can be, for those with parents inclined to take advantage, defined by a certain kind of excess. The number and intensity of child-centered activities on offer could overfill even the most ambitious and efficient parents’ schedule. My daughter’s friends, mostly third- and fourth-graders, invest significant amounts of time in dance and gymnastics, in baseball and martial arts, in after-school Mandarin and kiddie architecture. I know of at least one after-school financial-literacy class for the 10-and-under set.

The same rules of abundance and opportunity apply in theater. Across New York City are countless training programs for children who are interested in acting as a hobby or, possibly, a profession. In addition to ACANY, there’s the Children’s Acting Academy, Wright Way Coaching, Broadway Workshop, the Barrow Group, the Kidz Theater, Spotlight Kidz, and Spotlight Kids NY. There’s even a public middle school, the Professional Performing Arts School, that has been plunked down in the Theater District to accommodate the professional child. The classes in these institutions carve a path of increasing skill and dedication. Which means that, instead of swim meets, chess tournaments, or robot battles, parents will eventually be presented with the option to introduce their children to agents and managers, steering them toward paid work.

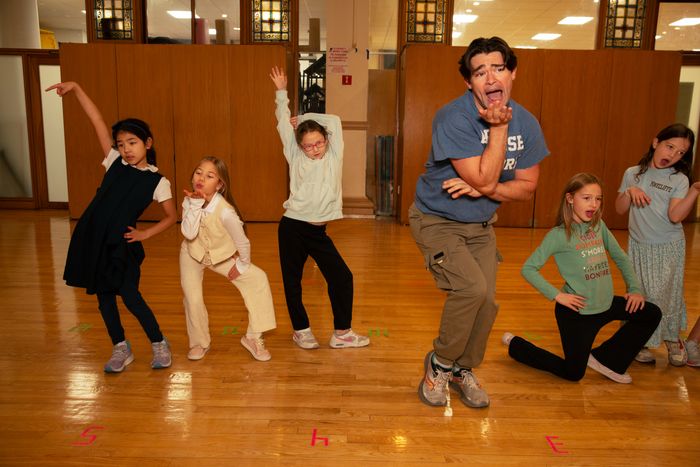

In her first production, June had a small role in Into the Woods Jr.: a total of two lines and a part in a handful of dance numbers. The older kids were nice to the younger kids. The younger kids supported one another. June loved it. She befriended one little girl — Brielle — who played Milky White, the cow, and whose family overwhelms the playbill every performance with advertisements congratulating their rising star. (Any playbill without a paean to Brielle now seems obscurely disappointing.) June then landed a role, in the fall of 2023, as Molly in a production of Annie Jr. I had a babysitter paint freckles on her for the first performance because I knew nothing about stage makeup.

It was winter when I realized where all this was going, post–Annie Jr. and on the cusp of The Little Mermaid Jr. We had just heard the news that an 8-year-old named Cecilia Popp (she goes by “Cece” and her surname is pronounced “pope”), a friend from Annie Jr., had been cast as 4-year-old Tommy in a revival of the Who’s famous rock opera. On Broadway. Cece had gone pro.

We were walking past the Hester Street Playground on our way to a friend’s house when June absorbed this news, holding hands with a level of casual comfort that is available only, at least in my experience, to parents and children. “This was on Broadway?” she asked. “How did it happen?” And then my daughter turned to me and said, “I want to be an actress.” Then the clarifying elaboration: “A child actress.”

Children have been performing on Broadway for as long as Broadway has existed. And as long as there have been kids onstage, there have been stage parents. Minnie Marx pushed her sons into vaudeville. Judy Garland’s mother, Ethel Gumm, put her daughter onstage when she was 2. (“She was very jealous because she had absolutely no talent,” Garland would later say.) Buster Keaton’s parents shared a billing with him as the Three Keatons; they were accused of child abuse for the pratfalls he did for their act.

The stage parents of our popular imagination are people who have lost something, somewhere, and are striving to regrasp it through their children. They crave their own fame and success and are interested in their children primarily as reflections of themselves. “Why did I do it? What did it get me? Scrapbooks full of me in the background!” complains Rose, the stage mom whose ambition drives Stephen Sondheim’s Gypsy, which just began a high-profile revival on Broadway. (Shirley Temple, to be fair to stage moms everywhere, loved her mother.)

But where the stage parent might, in past generations, have been considered a little too striving, the logic of modern parenting offers a kind of permission unavailable to Ethel Gumm. Millennial parents are constantly assessing our children to find the shape of them, gauging their passions for gymnastics, art, or, say, personal finance. We exist in the long tail of helicopter parenting and are practiced experience givers, doling out memories and skills as mindfully as possible. We tend to be optimizers ourselves — I am guilty of standing in the sunlight every morning (or every morning I remember) to improve my mood à la Andrew Huberman. All of which is to say that the jump to stage parenting looks more reasonable when everyone around you is meditating, eating right, and carting their children to a full schedule of soccer and Tae Kwon Do.

“We all want the best for our children,” Cece’s father, Frank Popp, told me. “If your kids are good at chess, you probably want to find them the best chess teacher. If they sing, we want them to have the best singing teacher.” In this case, the best singing teacher may lead to a gig that puts your child in front of a paying audience six nights a week with two matinees.

When June declared that she wanted to become an actor, my first response was to laugh and say, “I don’t think you do.” In my defense, it’s sometimes hard to tell how seriously to take one’s child. June’s day is filled with more ideas and schemes than I produce in a year. I am not immune, however, to parental striving. And my daughter is talented! She’s charming! I told her I would ask around.

Many of June’s theater friends had Instagram handles, most of which said “managed by mom,” “parent monitored,” or “mom” in the bio. Parents posted photos of their children holding copies of Playbill or singing onstage, sometimes with the hashtags #kidactor or #theaterkid, sometimes with uncanny first-person captions like “Working on my craft!” or “By the sea … thinking about what song to learn next 🎶.” ACANY’s account posts headshots of its current and former students with the words BOOKED IT stamped on them when someone lands a role.

The repeat parents at ACANY are all quietly enthusiastic about one another’s children. We nod at one another in the hallways outside the rehearsal space, watch one another tend to our kids, sometimes doling out compliments, sometimes identifying performers we don’t know by their role (“Baker’s wife, you sounded amazing!”).

The first parent I spoke with about putting June on a professional pathway was the mother of Beatrice Beggs — a tiny 8-year-old with the sweet, high-pitched voice of an even younger child — who had played Molly in a separate cast of Annie Jr. (ACANY frequently trains two casts at once). I knew from preperformance chatter that Bea had recently acquired an agent. “We got one by mistake,” her mom, Caitlin Goddard, told me. She had signed up her daughter, in the summer of 2023, for a camp that culminated in an agent showcase — and all of sudden Beatrice had professional representation.

Goddard is a Gyrotonics teacher and movement expert whose past as a “pole athlete” is commemorated in her Instagram handle: @blondeasianpole. She’s a self-proclaimed hippie with none of the fuzziness I associate with hippies. When we met, in a basement coffee shop on the Upper West Side, she rattled off a list of children, theater programs, and Instagram accounts I should be following.

Beatrice has an Instagram account, and Goddard has a particular talent for captions that are both humble and promotional. When her daughter signed with her agent, the caption read, “Celebratory brownie because this talented little lady booked an agent for commercial and voice-over work — 1 workshop, 1 showcase, 1 agent meeting & SHE GOT IT 🤯🤩😮.”

There is, Goddard told me, an ideal window of time for the aspiring child actor. Children get cast most often when they are somewhere between 7 and 13. “Any younger,” she explained, “and no one knows whether or not you can read.” Any older, and the same part might be played by an 18-year-old. The drop-off in roles is so pronounced that one mother I spoke with went so far as to describe a performer’s teenage years as a “black hole.”

Therefore, Goddard told me, the first thing you have to learn as a stage parent is not to wait. “You never know what’s going to happen, but this is exposure for them,” she said. “It’s exposure and training. Our kids’ talents — it comes to a head much sooner than it did for us.”

The second thing you have to learn is how to film an audition — and that an audition may come up at any time with deadlines that seem impossible to meet. You, and your child, should be available. Keeping up with all the auditions meant Goddard and Bea frequently recorded videos at 9:30 or 10 p.m., after Bea’s younger brother was tucked into bed.

The downside of not taking advantage of every opportunity that comes along is that your child may not be prepared to pursue their dreams, Goddard said. “And what’s the other thing?” she asked. “Oh, okay, the child is overscheduled.” She shrugged.

Parents might be nostalgic for an era when children spent their days outside throwing rocks, absorbed in productively unproductive play, but actually re-creating that ideal can feel impossible. Dorothy Savage, whose daughter, Honor, first signed with an agent when she was 7, pointed out that free time nowadays usually means sitting in front of screens, with all the attendant negative effects on mental health. “We’re living in an age,” she told me, “where keeping them busy with things that feed them is also a safety measure.”

Many of the mothers and fathers I spoke to had read, or were at least aware of, Jonathan Haidt’s The Anxious Generation. They were thoughtful about social media (witness all those googly-eyed emoji) but realistic about their ability to raise a free-range kid in a city as big as New York. As good millennials, of course, they were also susceptible to an overriding feeling of scarcity — that other kids are getting experiences that you have failed to give your own. It is hard to shake the feeling that without our help, our children might not thrive. But is it possible to fill our children’s schedules with “things that feed them” without adding more pressure to their lives?

Honor’s family offered a good example of how a hardworking parent might combine ambition with a sense of playfulness. Not long ago, I visited their Upper West Side apartment, where an eight-foot-tall blue screen leans, semi-permanently, against a wall. It was a Tuesday afternoon in the summer, and Savage had set up an enormous ring light at the foot of her bed, which was neatly made and covered in six rows of throw pillows. A computer was propped up on a music stand, displaying a section of a script. Savage and Honor, who recently turned 13, were elbow-deep in a closet, picking out clothes and calling out advice, explaining the art of the self-taped audition.

“Nowadays, you want to dress for a role,” Savage told me. “But not too much. There’s a balance.”

Savage handed Honor a notebook and a pen (the scene in question involved a Christmas list) and stood back, looking her daughter over. They had selected a bibbed skirt and a loose sweater and put Honor’s long strawberry-blonde hair in braids. “It looks good,” Savage said. Honor has perfect posture, and she accepted the pronouncement with a pleasant look on her face. She watched as her mother slid an iPhone into a holder in the middle of the ring light.

“Okay,” Savage told her daughter, taking a breath, “let’s go.”

Until three years ago, Honor, her parents, and her brother were living on a farm in Alabama. Savage ran a local theater nearby, and she invited a group of agents to see her students. “I was so surprised they wanted her,” Savage told me. “I said, ‘You mean the little girl with the teeth falling out of her head?’ ”

The family moved to New York in part to give Honor a better chance at a career. Their first apartment in the city was so small an earlier version of the blue screen barely fit. One time, Honor told me, her mother fell into the bathroom when they unfolded it. Closing the screen takes a specific full-body hip swish that both Honor and her mother tried to pantomime — there’s a reason it lives unfolded on the wall these days.

Until this year, when she started at a school in Manhattan for children in the performing arts, Honor took her classes remotely, scheduling her auditions and theater training around her academic work — or maybe it was the other way around. The day I saw her, she had a dance class in the morning, a voice lesson around lunchtime, a private tap lesson shortly after the voice lesson, a session with an acting coach over Zoom (for which Savage had to rent a rehearsal room adjacent to the tap room), then, in the early evening, a few hours of gymnastics.

“I’m a type-A person,” Savage said between audition takes while her daughter quietly but seriously considered her blocking. “But more of a disastrous type A. I love a puzzle piece in a schedule. I’m not a perfectionist; I truly can be a mess, but I enjoy it.”

Many of the auditions kids like Honor get are for voice-overs. (“Last week, we did an audition voicing an aardvark,” one mother told me. “What the hell is an aardvark supposed to sound like?”) Savage has an “isolation box” in her bedroom along with the ring light and blue screen. For voice-over auditions, she props the box up on its stand, tall enough that Honor can stick her head inside it. Recently, she voiced a dung beetle singing in harmony with a bee.

Savage usually has Honor do at least three takes. “One thing you have to remember is to heart your videos” — to mark them as favorites. “When I started this, I’d have to watch everything all over again to remember which one we liked in the first place.” Savage says it takes an average of 200 auditions before you get a role.

“Learning how to do a good self-tape is a journey all on its own,” Kim Pedell of Zoom Talent Management told me. “Parents have to learn to be readers so they can read with them. A lot of my parents think they need to read the line in a leading way. If you ask them that way, they’re going to singsong an answer right back to you. You don’t want a kid to look like they’re acting. That’s the beauty of kids acting.”

Goddard, in our first meeting, warned me that you need to have the kind of relationship with your child in which you can give them directions and they will listen. One mother told me that, by the end of every self-tape, her child has yelled at her at least once. Another told me she gives her son $5 for every audition — $10 if the performance is especially good.

The question of money looms in the background of all this work, but it’s hard to imagine anyone is doing this to get rich. Child performers are paid anywhere from $400 a week for an Off Broadway show to around $3,000 a week on Broadway. Some states now require at least 15 percent of that money be put aside in “Coogan Accounts” (named after Jackie Coogan, whose parents squandered his earnings). It’s not a lot if you are renting rehearsal spaces and paying for voice lessons, dance class, and acting coaches, which can cost thousands of dollars a year.

I met Cece Popp’s parents, Frank and Eunie, in Bryant Park one afternoon after they had dropped their daughter off for a matinee performance of Tommy. We spent the first half-hour discussing the ins and outs of their scheduling, which they track using a color-coded calendar.

During rehearsals, Cece would be in the theater from 11 a.m. to 11 p.m., with breaks for lunch and dinner that required the presence of a parent. “Frank would take her down or a babysitter would take her down and do the lunch thing,” Eunie said, “and then I would go down and do dinner and then Frank would go down and pick her up at night.”

Cece’s parents said that, despite those complications, the family was in a better spot than most. Their older son was in seventh grade — perfectly capable of being left home alone. The other three children working in Tommy were all from out of town. They had sublets in the city, and their parents would often switch off, one parent living in New York, the other in their hometown, for extended periods.

Rachel Braverman had to do something similar when she had two kids in traveling productions and two at home. She hired professional guardians for the children who were on the road and spent a lot of time flying back and forth to see them. “I’m sure this sounds totally insane,” she told me. “But all four of my kids are really happy. They’re really grounded, and all of them are doing what they love.” She did joke, however, that she has taken her Columbia law degree and “applied it to being an executive-assistant stage mother.”

For June and for me, the experience of youth theater has been far more relaxed, though I did realize to my horror that I have to work to keep from mouthing my daughter’s lines while she is onstage. Being at ACANY feels to June like joining a team. (“It’s like football,” my Texan father quipped, “without the head injuries.”)

Going professional can complicate this feeling of camaraderie, but there is not, at the moment, a huge glut of opportunities on Broadway for the child actor. There is no Matilda with its cast of 15 or so kids, no Billy Elliot with its ballet-dancing child star. Marc Tumminelli, the founder of Broadway Workshop, suggested that, in the face of these doldrums, parents should focus on training rather than on landing roles.

It is hard to overstate the talent of the theater kids I meet. When Cece first opened her mouth to sing “NYC” in Annie Jr., someone in the audience audibly whispered “whoa.” Beatrice is both adorable and poised. Honor can sing, act, and tap-dance without breaking a sweat. “Back in my day, a triple threat was like this rare bird,” Savage told me. “Now it’s like, ‘What tricks can you do? Can you do trapeze and fly a jet?’ ” Boys, as a rule, have an easier time of it because there are simply fewer auditioning. (“Girls, there are 17,000 more of them than boys,” said Pedell. “Boys have a meteoric success rate if they’re even a little talented.”)

Many professionals still talk about the “It” factor. Pedell says she has been in this business long enough to recognize someone who will draw your eye onstage. It’s a combination of talent and enjoyment — professionalism combined with some essence of kidness.

Honor is getting taller now and is visibly strong from gymnastics. Height can be a problem in child showbiz. There are riders in most kids’ Broadway contracts that limit growth to two or three inches. No one wants a Molly who can look Miss Hannigan in the eye. Savage says some theater kids keep wearing jumpers and braids well into their teens. “If that’s your look, then go for it,” she says, “but let’s be realistic here. Your average 13-year-old wears wide-leg cargos and a crop top.”

While Broadway opportunities are rare, June and friends had their eyes on one of the many touring productions looking for child actors. Frozen and Mrs. Doubtfire recently toured the U.S., while The Sound of Music was touring in Asia. And then, of course, there is the longtime pinnacle of child acting: a traveling production of Annie.

By the time the auditions for a new Annie, which would include a run at Madison Square Garden, were announced this summer, I was deep enough into the scene to hear about it the same day. A handful of parents called or texted me with the news, perhaps hoping that if I wrote about their child, it would improve their chances of being cast. When I told one parent about a child I was following for this story, the parent dismissed her chances immediately because she was “too tall.” Savage says she stays out of the “group chats” because the atmosphere can turn so quickly toward cattiness.

“Parenting has become a competitive sport even if you take out the specialty of talent,” Jenn Thompson, the director of the new Annie production told me. Thompson was in the original cast of Annie as a kid, playing an orphan named Pepper. Back then, though her parents were dedicated to her career, they were hands-off. For instance, Thompson took a cab by herself every day to the theater and back. “Parenting was so different,” she said. “We were so much more on our own.”

Performing has changed as well. Annie, Thompson believes, changed the perception of what a child actor was capable of and what a child-heavy show could achieve. Thompson and her friends took tap lessons, and there were certainly vocal coaches and acting coaches available. (“We were all active in our pursuit of mastery and employment,” she joked.) But the range and availability of theaters and classes back then pales in comparison to the current landscape.

Broadway shows themselves still preserve some parental distance. Parents are not allowed backstage in New York’s theaters. Child performers are tended, instead, by their guardians. Parents are comped one set of tickets, early on, then have to buy tickets like the rest of us. One father I met, whose son was playing Frank Jr. in Merrily We Roll Along, would listen from the lobby for the moment his son came onstage, measuring the reaction of the crowd.

In a traveling production like Annie, however, parents are necessarily more hands-on, which can lead to trouble. “The first year of the tour was right after the pandemic,” Thompson told me. “I didn’t really get to know the parents very well. We decided in the second year that we were going to talk to them a little bit more” so they would know what to expect. Thompson does not hire two casts, for example, because she doesn’t want any animosity between different Annies. She has done her best to limit phones and Instagram from the rehearsal space because actors and families had become competitive regarding the number of followers and likes their children were getting.

Now, Thompson is strict with her cohort of parents. If your child is under consideration for a role and you, for example, follow Thompson into the bathroom for a chat, your child will likely not get the part. “In a dance call, you’re watching the parents interact with each other,” she said. “Does it feel weird and competitive? Are people being jerks? Sometimes people don’t realize who’s watching.”

Once the kids are cast, Thompson talks to the parents about preserving an environment, in their homes or hotel rooms or wherever they are, that has nothing to do with Annie. Parents cannot attend rehearsal. They are not encouraged to buy tickets and see the show.

No parent I spoke with, no matter how involved, would own up to being the driver of their child’s ambitions. When one father admitted over the phone that his son had cried while rehearsing for an audition, his wife pointedly cleared her throat. “What?” he said. “It’s true!” But among the parents I met, even the most intense ones were constantly gauging when to push and when to hold back. “You have to know your children,” said Savage. “I don’t want them to feel pressured or that there’s an expectation to be other than really solid humans. If this is the route, great, and if it’s not, great. I don’t want them to think this makes them valid.”

No matter what your child is interested in — soccer, robots, swim team, theater, chess — parents are challenged, when spending this kind of time, effort, and money, to enable their children’s dreams while blunting the force of their disappointments. You invest all you can, but you cannot be too invested.

Tumminelli told me in this vein that lots of kids discover they don’t have the commitment necessary to be on Broadway, and it’s a reasonable choice to leave the professional track. “I mean, do you know any child lawyers or dentists?” he asked.

June’s commitment to the theater, so far, is unwavering. At the moment, you’ll most likely find her humming the music from Shaina Taub’s musical Suffs. She particularly likes a song sung by Woodrow Wilson and will occasionally alarm strangers by shout-singing, “Ladies must be commanded!” while walking down the sidewalk.

“If it brings your daughter joy and you can accommodate it, I would encourage it,” Thompson told me. “That doesn’t mean every day is a happy day.”

I have not yet started the hunt for an agent. I haven’t spoken to any managers, and June has appeared in zero showcases. I am caught somewhere between wanting to give her the best experiences and wanting to protect our time, both together and apart.

I watched June’s friends post videos this summer of their theater camps and workshops — they rarely miss a note. They sing and dance and, quite literally, do flips. I worry that my ambivalence will rob June of her limited window for child success. At the same time, I have visions of my sweet, thoughtful now-9-year-old screaming at me over the audition tape for a cartoon aardvark.

The appeal of a rock-throwing childhood — an aimless, pre-striving, in-the-moment activity — is in its expression of personhood outside a system of work and rewards. For now, there is still a looseness to my evenings with June: a chance to listen to recounted playground dramas and tell dumb jokes. I am too jealous of this time, maybe, too protective of my life as a parent with no preceding qualifiers, to properly optimize my daughter’s experiences. This isn’t, I’ve realized, a measured decision I’ve made about promoting unstructured time. It is about the fact and nature of June’s hand, still comfortably in mine while walking down the street.

That said, when a friend of a friend recently told me there was a small part for a “pensive” 8-year-old in an upcoming indie film, I sent over an audition tape within hours. In the tape, filmed by our babysitter, June sits in a chair against a brick wall, reciting her lines and picking at her knee, pensively. One audition. One callback. BOOKED IT.