Dallas is a long way from Metropolis, but within the space-age architecture of the Dallas Theater Center, Superman was preparing to take flight. It was 2010, and the organization was on the verge of premiering what it hoped would be one of the biggest shows in its history: an entirely reimagined take on the 1966 Broadway production It’s a Bird … It’s a Plane … It’s Superman. To the extent that the original show had any legacy, it was as a strange artifact from a time before people had quite figured out how to bring superhero fiction to the grown-up masses; a tale not based on any existing Superman story and lacking most classic Superman characters. The Dallas production had attempted to rectify all of that. In cooperation with the surviving original writers and composer, scenes had been rewritten, the songs had been reframed, and a few numbers that had been cut from the original run were added. All systems were go.

And then DTC artistic director Kevin Moriarty got the letter from DC Entertainment’s lawyers.

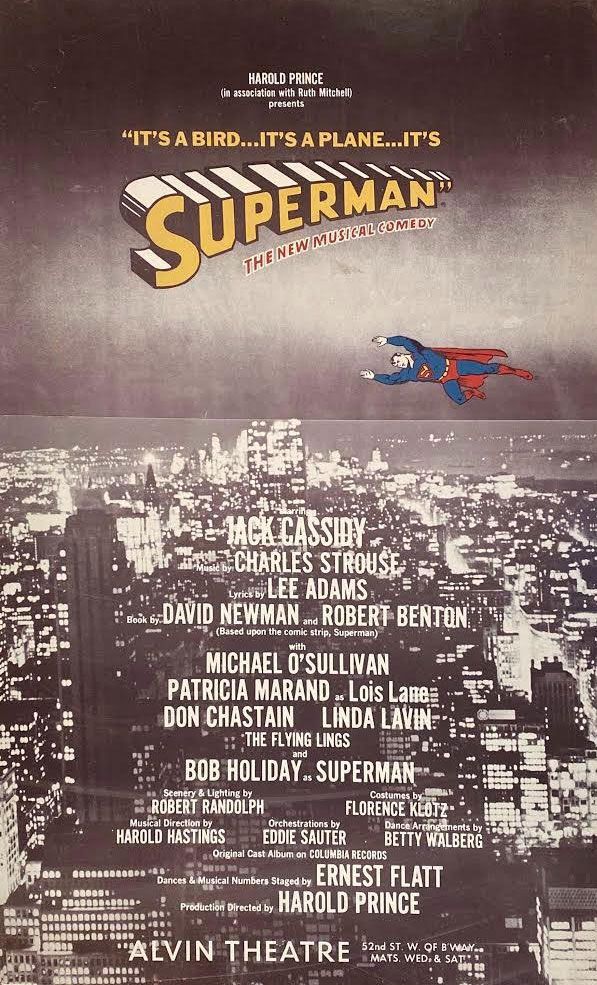

“They said, ‘You don’t have permission to do this. You’re making changes to a show you don’t have permission to produce,’” recalls Moriarty, who had developed the revival with Riverdale creator Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa. The project was a labor of love for the pair, who shared an unlikely appreciation for the 1966 production — a show that had a dizzying pedigree. Its songs were composed by Charles Strouse and Lee Adams, the duo behind Bye Bye Birdie and Annie. Its book was penned by Robert Benton and David Newman, the screenwriters who wrote Bonnie and Clyde and Kramer vs. Kramer and worked on the 1978 Superman movie. It was directed by Broadway legend Harold Prince, a man with 21 Tonys to his name. All that, and it was a musical about Superman, one of entertainment’s most enduring pieces of intellectual property. It was true that Moriarty and Aguirre-Sacasa, both of whom possess an abiding passion for musical theater and comic books, didn’t have permission from DC. They didn’t think they needed it.

Typically, all that’s required to get a Broadway show officially revised is the approval of the original creators — and that, the pair had. Moriarty replied to DC explaining as much: “We’re working with the very writers themselves.” DC wasn’t persuaded. As Moriarty recalls, “They said, ‘Here’s the thing: We are not going to close down your production. But we do not recognize the right of this production to exist. And we’re going to do everything in our power to stop it from ever having a life after this.” Which meant that once again, Superman and his musical were getting an early, kryptonite hook.

For roughly two and a half decades after Superman introduced the concept of the superhero to the public in 1939, DC was king of the comic-book newsstand. It would fire off millions of copies of its adventure stories every month and rake in cash from the grubby little hands of the nation’s children, deftly swatting away rival publishers like Charlton and Timely (the latter eventually being renamed Marvel). One of DC’s fans happened to be the preteen son of a man named David Newman, who worked as a writer. Newman, who died in 2003, had cut his teeth as a journalist, producing pieces primarily for another publishing icon of the decade, Esquire. It was there that he met fellow writer Robert Benton. Fast friends, the pair had aspirations of becoming more than ink-stained wretches, and though they had already written a screenplay that would change pop culture, Bonnie and Clyde, as of 1965 no one had picked up that script.

Then, in a classic instance of New York City networking, a bizarre opportunity arose. “Byron Dobell, an Esquire editor, said, ‘There’s some friends of mine I’d like you to meet,’” Benton recalls. “And it’s Lee Adams and Charles Strouse.” For aficionados of musical theater, Adams and Strouse were household names — but, like Benton and Newman, they were struggling at the time. The duo had exploded onto Broadway when they wrote the music and lyrics for 1960’s Bye Bye Birdie, but 1962’s All American and 1964’s Golden Boy — despite being co-written by Mel Brooks and Clifford Odets, respectively — both flopped. The pair was on the hunt for something that could restore them to glory.

“Byron said, ‘They’re looking for materials. Why don’t you meet with them?’” says Benton. He and Newman felt they needed to bring something to the meeting. “So David and I thought about it, and by chance, his son — who was about 10 — found a copy of Superman in their apartment and said, ‘Why don’t you do a musical about Superman?’”

It was as good an idea as any, and, without consulting with DC to see about clearance, they presented it to Adams and Strouse. As it turned out, the Broadway guys had themselves been huge Superman fans in their Depression-era youths — “Every kid was,” Adams says. What’s more, they felt that Benton and Newman, who were younger, could help them bridge the widening generation gap. As Strouse recalled in his 2008 memoir, Put On a Happy Face, “Bob and David were both smart and funny as hell. They were young and connected to the ‘hip’ world. We all clicked.”

Luckily for the quartet, Superman editor Mort Weisinger was, as Superman historian Glen Weldon recalls, “among other things, a hustler, and a guy who was very interested in getting the Superman name out there.” Weisinger helped arrange a rights deal through longtime DC chieftains Jack Liebowitz and Harry Donenfeld, one that contained just a few stipulations. One was that they could only use a handful of existing characters: Superman, Lois Lane, Daily Planet editor-in-chief Perry White, and photographer Jimmy Olsen. The other was that the show couldn’t be called Superman: The Musical, which explains its eventual unwieldy, ellipsis-filled title.

Once the deal was done, everyone had to actually write the thing. One aspect everyone agreed on from the jump: They didn’t want this to be a kiddie show. “The biggest problem was taking a character that was a children’s character and making it into adult subject matter, something that adults could hopefully enjoy,” Benton recalls. “Do you just do the original material? And how could you, without making fun of it?”

He and Newman opted to keep things slightly tongue-in-cheek, to include a lot of contemporary references that only grown-ups would get, not to adapt any particular comics tale, not to tell an origin story, and to obey the character quota by coming up with a set of new villains. The rogues gallery featured Dr. Abner Sedgwick, a scientist driven to madness by his constant losing of the Nobel Prize. There was Max Mencken, a snotty Walter Winchell pastiche who writes for The Daily Planet. And then there’s the part of the show that has aged most poorly, a gang of criminal Chinese acrobats called the Flying Lings. (On the subject of the Lings, Benton notes, “It’s a piece from another time that reflects another world.”)

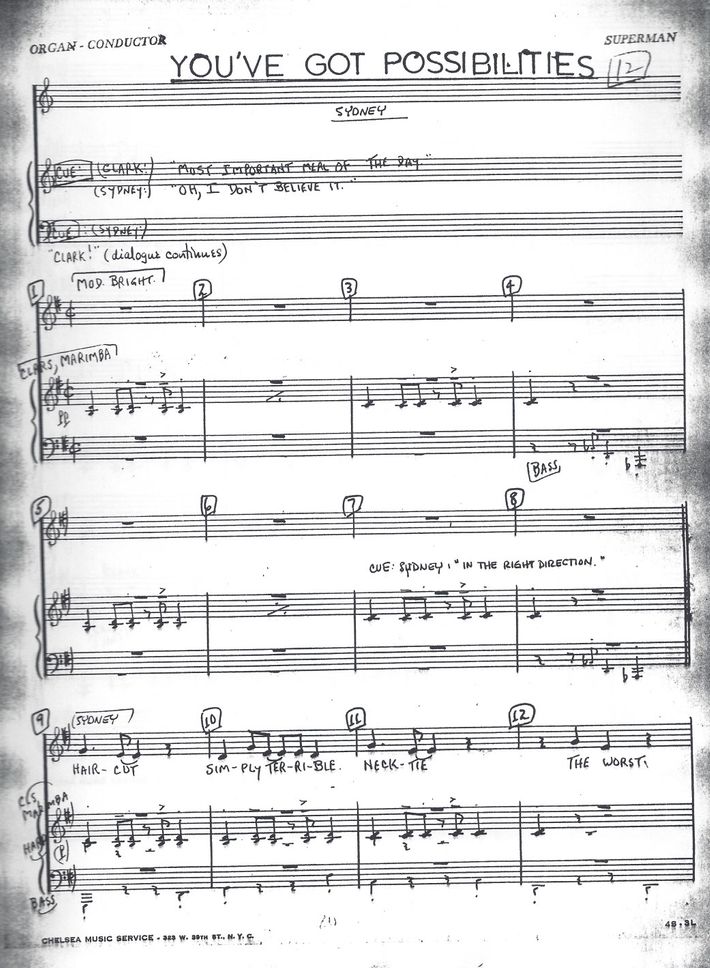

There was another new character, one whose presence would serve as a muse for the most enduring song of the show. Max has a sassy girlfriend and girl Friday who goes by the name of Sydney Carlton, eternally put-upon by her narcissistic beau-boss. Midway through the first act, Carlton shows a little interest in milquetoast Clark Kent, singing to him about how he could be sexy if he made a few personal tweaks. The ditty Strouse and Adams came up with for that moment was dubbed “You’ve Got Possibilities,” and the music came to Strouse during a walk with his wife. “We had a home in Fire Island,” he says. “I remember walking in the rhythm of” — he hums the tune — “and there was a certain kind of bounce where you could always fool people where it came, on the downbeat.” He cracks up while recalling Adams’s lyrics, in particular one quadruplet of lines in which Sydney disses Clark’s out-of-date style:

Collar? Pure Peoria.

That hat — oh no!

I’m not Queen Victoria!

This suit has to go.

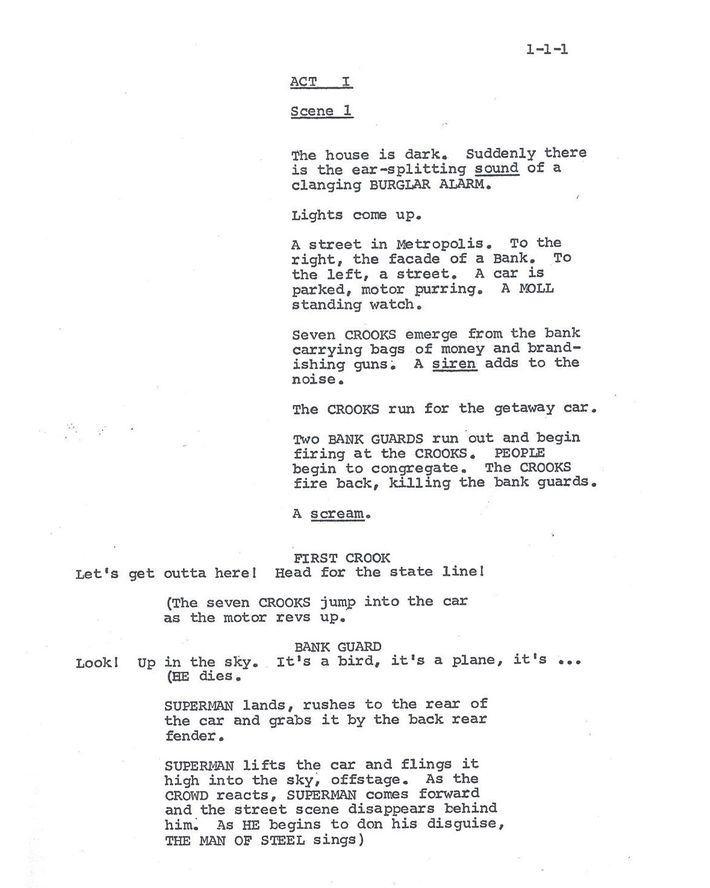

Benton, Newman, Strouse, and Adams whirled this dramatis personae together into a story and song list that was by turns boilerplate and bizarro. “The house is dark,” reads the first stage direction of the script. “Suddenly, there is the ear-splitting sound of a clanging BURGLAR ALARM.” The lights come up, and we’re in scenic Metropolis, where crooks are attempting to escape after robbing a bank. Superman soars down on wires from the wings, promptly “lifts the car and flings it high into the sky, offstage” — quite the ask for a stage show — then sings the show’s first number, “Doing Good,” which features stanzas such as:

It’s a satisfying feeling

When you hang up your cape

To know that you’ve averted

Murder, larceny, and rape!

The ensuing 90-odd pages were light and loopy. Abner concocts a scheme wherein he gets a wing of the local university named after the Man of Steel, then gets the Lings to help him blow up a nearby building during the dedication ceremony. Supes is humiliated by the fact that property was destroyed while he was doing a photo op, and, depressed, he locks himself up in his apartment. Meanwhile, Max becomes obsessed with outing Superman’s secret identity and neglects Sydney, and Lois strikes up a romance with Abner’s lab assistant, Jim Morgan. Abner and the Lings team up with Max to take Superman down at an abandoned power station, but, in a truly strange deus ex machina, the Lings turn out to be communist agents and declare that they’re going to nuke Metropolis. Superman snaps out of it and takes out the Chinese baddies, Abner falls into a power reactor, Lois realizes she loves Clark more than Jim, Sydney berates Max, and, just before the curtain falls, the Man of Steel flies off to stop the Maoist missile, declaring, “This is a job for Superman! Up, up, and awayyy!”

There are more than a few highlights along that journey. Abner’s psychoanalytic trash-talking with Supes is a decent breakdown of the insufficiencies of superhero fiction (“Good is a relative term. If I swat the fly, it may be good for me, but is it good for the fly?”), and he gets a delightfully goofy number called “Revenge,” in which he lists Nobel winners he resents:

That dopey Wolfgang Pauli for his work in fission?

I used to help that punk with long division!

And Fermi for his brilliant neutron system?

That bum, he wouldn’t know a neutron if it kissed him!

Max and Sydney are the Benedick and Beatrice of the show, constantly charming the audience with their bickering, as in Sydney’s ode to her beau’s narcissism, “Ooh, Do You Love You”:

From the moment you saw you,

How your heart began to pound.

It was not infatuation,

No, it was much more profound.

Then you smiled and you trembled

And the thunder rolled above.

From that day you can’t forget

As you lit your cigarette,

You just knew it was love.

For his part, Superman is played as an earnest stalwart of goodness, and the show only lightly ribs him for it. Jim Morgan gets a fascinating song about the uselessness of the human race titled “We Don’t Matter at All,” which feels very au courant in 2020:

Oh sure, every hundred years or so

We come up with a Gandhi or a Michelangelo.

“Hooray! Ain’t that dandy?” we say,

Then we muck things up

In the same destructive way.

But Morgan is otherwise a dull character. Worst of all is the depiction of Lois: She is, to put it mildly, a bit of a sap, deprived of all agency, who belts out “What I’ve Always Wanted,” an homage to domestic tranquillity that is anti-matter to the then-nascent women’s-lib movement:

What I’ve always wanted,

What I’ve always wanted:

Being just a wife; that corny life

Is what I’ve always wanted.

A dogwood tree, the A&P,

Conformity,

Green stamps in a book,

Making like a cook.

And the less said about the Flying Lings the better.

Benton, Newman, Adams, and Strouse approached famed Broadway producer David Merrick to back it. “David Merrick was like a Superman villain,” Strouse recalls. “He said, ‘Oh, great!’ and then he dropped us and lied to our lawyer.” Undeterred, the quartet turned to the 38-year-old Hal Prince. “The guys wrote great material, all of them,” Prince told me in 2017, two years before he died. “And I thought that it would be a lot of fun.” So he said he’d produce the show, with one stipulation: He also had to direct*. With Prince onboard, they got the green light to open at the Alvin Theater on 52nd Street.

When the casting call went out, actors clamored to be part of a piece of pop-culture history. Up-and-coming chanteuse Linda Lavin had worked with Prince on a previous show and was determined to land the part of Lois Lane. She bought a Superman comic, aped Lois’s flashy style — green hat, orange ribbon — and went to a photo booth where she could get five pictures for a dollar. “I took these strips of myself as Lois Lane and glued them to frames in the comic, covering Lois’s face with mine, and I sent it to Mr. Prince,” she recalls with a laugh. “He called me after he received it and said, ‘This is brilliant, but you can’t be Lois Lane. You’re just not midwestern enough.’ I was a Jewish girl from Portland, Maine, so yeah, I saw it.” She was instead given “You’ve Got Possibilities” as an audition side, nailed it, and was cast as Sydney. At her side as Max would be one of the great comic actors of the day, Jack Cassidy, who’d just two years before won a Best Featured Actor Tony for She Loves Me.

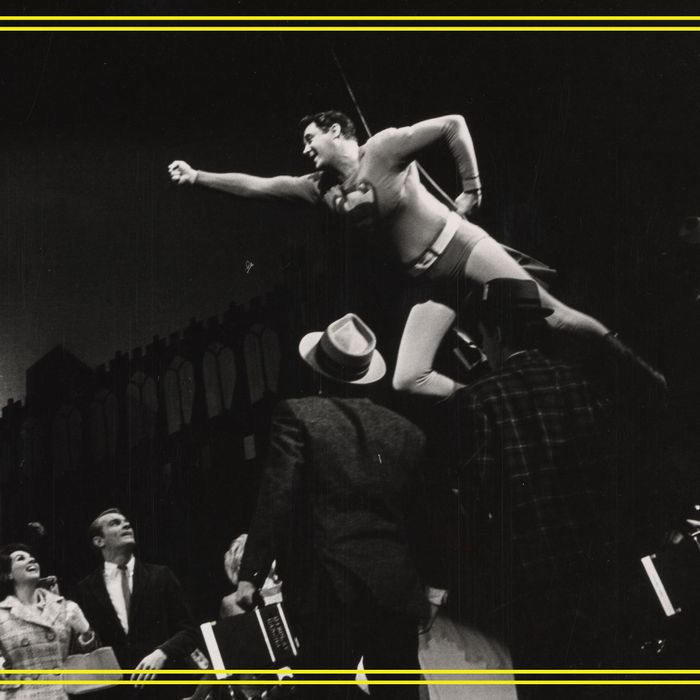

New characters in supporting roles are one thing, but Superman? Well, that’s a cape of a different color. Everyone thought finding someone with the gravitas to nail the Last Son of Krypton would be an uphill battle. Then they met Bob Holiday. A towering, broad-chested Brooklynite in his mid-30s, Holiday had grown up watching the Kirk Alyn–starring Superman movie serials and idolized the character. He’d toiled in dinner theater and comedy clubs before making his Broadway debut in 1961 opposite Tom Bosley in Fiorello! When he tossed his hat in the ring for It’s a Bird, he provided the producers with one of their easiest decisions.

“At the start of auditions, a bunch of guys were lined up,” recalls Adams. “The first guy who walked up was Bob Holiday, and that was it. It’s one of those strange things. We saw a bunch of other people, of course, but he was obviously the one.”

Rehearsals were followed by performances for potential backers, and those were followed by a troubled tryout in Philadelphia. “We got the worst reviews I had ever read in my life from the Philadelphia critics,” Benton recalls. “It was devastating.” So they went back to the drawing board: Out went a Max number about being a columnist called “Dot Dot Dot,” as did a lonesome Lois ballad entitled “A Woman Alone,” among others. In came “So Long, Big Guy,” a tune where Max disses the temporarily retired Supes, optimized for Cassidy’s distinct comedic sneer. Though Adams and Strouse were used to bracing critical attacks, Benton and Newman were newbies, and the rewrite process was agony. “David and I would work all day, we would turn in pages to Hal, we would go off and wait for curtain time that night,” Benton says. “There was a penny arcade not far from the Shubert, and we would sit there playing ferocious games of pinball, and looking at people thinking, God, these people have normal lives. I miss the idea of having a normal life.”

Their endurance paid off. Previews began in the spring of 1966, and the show opened on March 29. Crowds flocked to the Alvin. “It got as good reviews as any show I’ve ever done,” Prince recalls. Even formidable New York Times theater critic Stanley Kauffmann turned in a glowing assessment: “It is easily the best musical so far this season,” he wrote. “I add at once that it would be enjoyable in any season.” Everyone involved in the production was over the moon.

As the performances went on, kids went crazy for Holiday, who regularly invited crowds of children backstage so they could meet him in character. “He started to believe he was Superman,” Strouse says. “He fell one night when the shackle attached to his harness broke,” recalls Toni Collins, a longtime friend of Holiday, who died in 2017. “He dropped six feet to the ground, bounced back up, turned to the audience, and said, ‘That would have hurt any mortal man!’” The crowd erupted into a standing ovation.

The fervor didn’t last. Enthusiasm swiftly dried up. Sales dwindled. After 129 performances, the show closed on July 17. Sources place estimates of the show’s cost at $400,000 to $600,000, — an ungodly sum for the period, making it one of the most expensive flops in Broadway history up to that point. That premature death still stings for everyone involved, and they all have their pet theories about what went wrong.

“Hal Prince didn’t have the right advertising for it,” suggests Strouse’s wife, the director-choreographer Barbara Siman. “I don’t think he knew what he was doing. I think he just thought it would take off. I don’t think he produced it properly.” Benton theorizes that the ambiguous nature of the intended audience scared off adults: “I think people thought it was a kids’ show, and it was not a kids’ show,” he says. The price may have been another factor. As the Times reported, in an effort to get butts in seats during an overall box-office slump for New York theater since 1965, the show was set up to have dirt-cheap $2 tickets available — but only if you bought them in advance by mail. When purchased at the theater, as was customary, they were $12. The next-highest-priced show at the time — On a Clear Day You Can See Forever, in case you were wondering — was $10.95.

But the one culprit nearly everyone mentions is Superman’s eternal rival for the hearts of geeks: As Strouse puts it, “We were hurt by Batman.”

By sheer coincidence, the famously campy Batman TV show starring Adam West debuted just a few months before It’s a Bird and quickly became a surprise sensation. That meant the public could get its dose of superhero fiction without having to wait in line at the ticket counter. “Everybody was seeing Batman for free,” Prince said, “and they go, ‘I’ve seen it.’”

Cassidy and the actors playing Abner (Michael O’Sullivan) and Lois (Patricia Marand) got nominated for Tonys, but none won. There was an original-cast recording, and “You’ve Got Possibilities” became a lasting, if minor, addition to the American Songbook, but the script was never published in the mass market, so listeners had no clue about the story. DC never incorporated any of the new characters into the comics. In a strange coincidence, Benton and Newman ended up co-writing the hit Superman movie more than a decade later (Benton swears their hiring had nothing to do with the musical), but they kept their old ideas out of it.

It’s a Bird was not mourned by the press or historians. Nevertheless, copies of the cast recording ended up in the hands of the curious few who stumbled across it. In some cases, they became enchanted by this curio, and two such enthusiasts were Kevin Moriarty and Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa. Both men had grown up fetishizing musical theater and comic books alike, and Moriarty, in particular, fawned over It’s a Bird after he found an LP of the cast recording at the library during his rural Indiana childhood. The strange show remained an obsession of his throughout his life, but his career as a director was oriented toward new works and bold reinterpretations of the classics, so, for most of his life, it didn’t even occur to him to stage it. That all changed after he got the Dallas gig in 2007. A couple of years in, he wanted to stage a musical that would entertain but wasn’t overdone. Around that time, he found himself in correspondence with Strouse and wound up at the latter’s lavish Manhattan apartment.

As Moriarty recalls, “I happened to ask him, ‘Would it ever be possible to go back into [It’s a Bird] and adjust the script for a contemporary audience?’ I asked this in the most careful, sideways way possible. But he immediately said, ‘I’d love that show to have a future life! Let’s do it!’” Moriarty, elated, finished up with Strouse and ran down to the street outside. He was friends with Aguirre-Sacasa, then known mainly as a playwright, and called him from the sidewalk. “I said, ‘I have a crazy question. I was just talking to Charles Strouse —’ And that’s all I got out,” Moriarty recalls. “He said, ‘Oh my God, is it Superman? If it’s Superman, I’m in!’”

Somewhat surprisingly given the show’s failure in its original run, there had been past attempts at reviving it. The strangest occurred on February 1, 1975, when ABC aired a TV-movie version of It’s a Bird, a deliberately sloppy rendition that was thrown together over the course of three days of shooting. Though it starred a few minor notables — M*A*S*H’s Loretta Swit, eventual Emmy- and Golden Globe–nominated actress Lesley Ann Warren, Mel Brooks staple Kenneth Mars — it couldn’t overcome a lack of clear artistic vision. “They didn’t have a clue what they were doing,” recalls David Wilson, who played Superman. “We had a week to rehearse. A lot of the stuff was just improvised when we got there.”

(The TV version featured many changes to the script, such as replacing the Lings with Italian mafiosi; the addition of a self-aware narrator (sample dialogue: “Will Superman make it in time? Stay tuned for chapter three: ‘Superman Makes It!’”); a trendy pop-psychology therapy session for Supes (“Did it ever occur to you that X-ray vision is just another word for voyeurism?”); and a deus ex machina wherein Max gets a case of hiccups so bad that they cause Abner’s villainous lair to explode. Wilson recalls critics’ reviews of the performance being abysmal. (Just as bad was the assessment of a surprising attendee of an early screening who was friends with Warren: “I remember Bette Midler came to the screening room for the edit,” Wilson recalls. “And she was, like, horrified.”)

For nearly 40 years afterward, the only way you were able to see It’s a Bird was if you went to a local theater’s production of it. Script company Tams-Witmark made the show available to license, but its dubious reputation and the technical impediments of flying Superman around in a harness almost certainly scared people away.

But despite its rocky past, Moriarty and Aguirre-Sacasa were undaunted. The pair got the additional permissions of Adams and Benton, as well as Newman’s estate, and turned around a revival for the Center’s 2010 season. It was a near-total reworking of It’s a Bird, one that kept most of the score but jettisoned virtually everything else. Aguirre-Sacasa wrote a book that had no trace of Abner, Sydney, Jim, or Max. In their place were classic figures from the Superman mythos. The songs of Abner and Max were given to Lex Luthor. Sydney was replaced by classic Daily Planet gossip columnist — and rival for Superman’s affections — Cat Grant. Gone were the Lings; in came a group of old-school Superman villains from the 1930s and ’40s.

The whole thing was set in those early days of Supes and was designed to capture the earnest glory that had made the character a hit back then. “You kind of make it an old-fashioned musical like Oklahoma! or Carousel,” Aguirre-Sacasa tells me. Lois was given far more agency, and the show concluded with Superman revealing his secret identity to her and gently flying her upward in a tableau of affection. (She was also played by a Black woman named Zakiya Young; additionally, Superman’s birth father and Perry White were also played as people of color by Hassan El-Amin.) Several songs that had been written for the original production and cut before the premiere were re-added, such as one sung by a chorus of Daily Planet staffers called “A Bunch of Happy People” and an ode to Superman sightings called “Did You See That?” Strouse and Adams even wrote a new song, “Superman’s Oath,” for Supes to sing to a group of Boy Scouts, one of whom was written to be the original Captain Marvel’s boyish alter ego, Billy Batson. The whole thing was a fan’s dream.

But when showtime arrived, DC Entertainment didn’t care about any of that. Strouse had shown Moriarty and Aguirre-Sacasa the mid-’60s agreement between DC and the creators, and it was, as Moriarty recalls, “one page and very, very general.” They operated as though they didn’t need DC’s permission and went ahead with the show, getting it fully ready for performance and selling reams of tickets. Then, at the last minute, they got that notice from DC’s lawyers. The attorneys argued that the 1960s licensing deal for It’s a Bird had only allowed for the creation of one musical about Superman, and that this was, for all intents and purposes, a second one. DC declined to comment for this article, but Moriarty recalls not being able to speak to anyone at DC except its legal representation. He couldn’t appeal to any creative partners.

“You put your heart and soul into something and then you’re bummed when it’s said, ‘You can only do this once,’” recalls Aguirre-Sacasa. Moriarty thinks it was all a matter of protecting the brand. “The DC universe at the time was in the midst of preparing to relaunch Superman in the movies,” he says. At the same time, there was already Spider-Man: Turn off the Dark on Broadway, and Marvel was facing bad PR owing to the troubled production of that Julie Taymor show. And Moriarty suspected at the time that DC wanted their new movie Superman to be darker, as he indeed turned out to be in 2013’s Man of Steel. “Having a bright musical-theater Superman was absolutely not what their brand was looking like at the time,” he says. Or perhaps it was as simple as not wanting to lose control of a Superman product. Siman — who, along with Strouse, adored the Dallas version — says, “They just didn’t want another version out there at the moment.”

Whatever the reasoning, DC made its position clear: It wasn’t going to stop the Dallas production, but it could never be performed again. What’s more, the players couldn’t use the names of any characters not already present in the 1966 version. Luthor became Max, Cat reverted to Sydney, the classic supporting villains lost their names, and so on. The show was a hit, but when it ended its brief run, the script was put under lock and key, never to be published or distributed.

A few years after the defeat of the Dallas production, the original show made its way back to the spotlight with a partly staged concert production that ran for a few days at New York City Center. It garnered a weird review from Ben Brantley in the Times, which named it a Critic’s Pick while constantly taking jabs at it (e.g., “This is purposefully disposable entertainment”). But that was just a one-off.

Amateur productions of the Broadway version have cropped up here and there over the years but always with considerable thematic difficulty. Justin McElroy, co-host of the podcast My Brother, My Brother, and Me, put on a production alongside his wife, Sydnee, starring local kids in their hometown of Huntington, West Virginia, a few years back. “It doesn’t even really make a hero out of Superman — it makes a ditz out of him. It’s one of those shows where it could have really benefited from being revisited and retooled.” And so it was: The Children’s Theatre of Cincinnati created a drastically edited, hourlong, completely clean version of the show that can be easily performed by children. Improbably, DC has allowed that iteration to become a licensable script for schools or community theaters. Perhaps It’s a Bird will live on as the kind of thing one fondly remembers doing in junior high.

And yet there’s always a chance of revival for what may have been the greatest version of all: the Dallas cut. Aguirre-Sacasa, who now works with Warner Bros. on Riverdale, told me in 2018 that there’s “a glimmer of hope of maybe getting a chance to do that again.” After all, DC has changed a great deal in recent years, allowing shiny versions of its characters in TV shows like The Flash and Supergirl — both of which have featured musical numbers. Moriarty is currently struggling to save his company in the wake of the pandemic, so reviving It’s a Bird isn’t a priority. But when I ask if he’s emboldened by the newly announced release of the so-called Snyder Cut of the 2017 DC film Justice League — another piece of DC media that was never supposed to see mass distribution — he laughs.

“Nothing would make me happier,” he says. “One of the many things I love about comic books — and I know it drives some fans crazy — is that dead does not mean dead.”

*The original version of this story incorrectly stated that It’s a Bird was the first show Hal Prince directed. We regret the error.