Spoilers follow for the Prime Video limited series Swarm, all seven episodes of which premiered Friday, March 17.

In Swarm, the sound of buzzing bees is a portent of violence. As the limited series follows Dre (Dominique Fishback) on a killing spree in honor of her dead best friend Marissa and their favorite artist, pop star NiÔÇÖJah, an insect drone enters the sound mix ÔÇö┬áa nod to the showÔÇÖs barely veiled references to Beyonce╠ü and her committed fans, the Beyhive ÔÇö┬ácueing DreÔÇÖs internal shift into simmering frenzy. When MarissaÔÇÖs family kicks Dre out of her funeral, when Dre attacks a man who mocked Marissa online, when Dre approaches NiÔÇÖJah and bites into her flesh: buzz buzz. But the aural anxiety of Swarm┬áalso signals DreÔÇÖs desire to be seen and heard, to connect with someone as she once did with Marissa. As Swarm moves Dre around the country, it pokes and prods at what obsession and loyalty do to an individual, positioning those guiding forces as distorted reflections of the same desire for closeness. ItÔÇÖs why SwarmÔÇÖs fourth episode and midway point, ÔÇ£Running Scared,ÔÇØ is simultaneously so intriguing and frustrating: It finally builds out how Dre sees herself, especially in relation to other women, but too quickly abandons its sly look at how these bonds can be warped and weaponized.

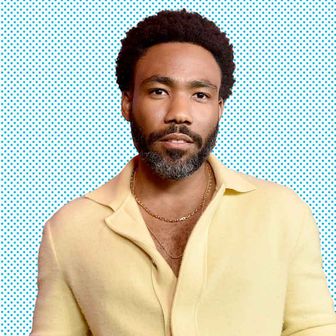

Co-creators Donald Glover and Janine Nabers primarily tackle two kinds of obsession within Swarm: sisterly and smothering, and devious and delusional. The former encompasses DreÔÇÖs adoration of Marissa (Chloe Bailey), who dies by suicide at the end of premiere episode ÔÇ£StungÔÇØ after sheÔÇÖs unable to reach Dre in a moment of crisis. Although we meet the two at a point when Marissa has grown weary of Dre, Swarm fills in years of friendship that began when Dre was adopted by MarissaÔÇÖs family. As teens, the girls saw NiÔÇÖJah together; as adults, they try to take care of each other despite financial shortcomings and near-estrangement from MarissaÔÇÖs family. As flawed as this relationship is, thereÔÇÖs a loving core that counters DreÔÇÖs other, increasingly troubling pairings with pop star NiÔÇÖJah and cult leader Eva, both of which fall under that ÔÇ£devious and delusionalÔÇØ category.

NiÔÇÖJah is DreÔÇÖs primary infatuation, and in every episode, she is doing something to prove her loyalty, whether thatÔÇÖs spending thousands of dollars she doesnÔÇÖt have to see the ÔÇ£queenÔÇØ perform or murdering Twitter trolls. Swarm gets a lot of glee out of mocking NiÔÇÖJah through critical tweets and detractorsÔÇÖ rants, but the series isnÔÇÖt interested in taking direct aim at Beyonce╠ü as an artist or entertainer. We see NiÔÇÖJahÔÇÖs music videos but donÔÇÖt see her speaking to press or to fans; Swarm fails to develop her personality or messaging, so she remains just a symbol to Dre. Yet the series also doesnÔÇÖt commit to examining what kind of groupthink, peer pressure, or single-mindedness drives fans like the Swarm. NiÔÇÖJah is presented neither as a performer mobilizing her supporters through social media nor as a celebrity who spends time dropping clues and hints to her followers. The series suggests Dre has dissociative identity disorder by veering her from stammering and awkward to uninhibited and carnal, but it avoids a definitive diagnosis on fandom in general. Instead, Swarm focuses on DreÔÇÖs homicidal reaction to MarissaÔÇÖs death and how she fuses Marissa and NiÔÇÖJah together in her mind. The friendship Dre and Marissa can no longer have transfers to a parasocial relationship between Dre and NiÔÇÖJah; the forgiveness Dre can never receive from Marissa becomes Dre needing NiÔÇÖJahÔÇÖs forgiveness for biting her in episode three.

Following a spree in which Dre kills a number of men she believes wronged Marissa or NiÔÇÖJah, ÔÇ£Running ScaredÔÇØ sees Dre fall in with a cult of white women living in rural Tennessee. Here are women who are, like Dre and Marissa were, practically joined at the hip, in tune with each otherÔÇÖs impulses and cravings, and equally likely to snipe at or support one another. And also like Dre and Marissa, these women have mixed up affection and codependency as they jockey to be family to each other. The episode is the closest Swarm comes to making an argument about the specific ways women can both empower and enervate each other within vulnerable or fraught circumstances, and the series does itself a disservice by not spending more time exploring the contradictions within these dynamics or how they fuel obsession.

Directed by Ibra Ake and written by Ake and Stephen Glover, ÔÇ£Running ScaredÔÇØ begins with Dre driving to Bonnaroo to see NiÔÇÖJah. When a white cop wonÔÇÖt leave her alone on the road, a white woman named Cricket (Kate Lyn Sheil) intervenes and chases him off with accusations of racism. Like other white women in the Glover brothersÔÇÖ work, Cricket is self-involved (ÔÇ£I got rid of him for youÔÇØ) and self-serving (ÔÇ£I love talking to youÔÇØ even though Cricket has started, and dominated, the conversation), and strong-arms Dre into tagging along to the mansion where she and her friends are staying for Bonnaroo. What Cricket doesnÔÇÖt mention is that all these women are under the thrall of the enigmatic Eva (Billie Eilish), who speaks in typical millennial self-help jargon with some casual cultural appropriation tossed in: Their rural location is ÔÇ£the best reset,ÔÇØ Dre has ÔÇ£a great aura,ÔÇØ Eva and her circle of friends are ÔÇ£the tribe.ÔÇØ At first, Dre is unsure of Eva, whom Eilish plays in a cleverly muted way; her tone is almost coquettish when she tells Dre sheÔÇÖs ÔÇ£a goddessÔÇØ and ÔÇ£specialÔÇØ ÔÇö just like NiÔÇÖJah ÔÇö and blas├® when she explains to Dre that their group specializes in ÔÇ£unlocking female potential.ÔÇØ Her tranquil demeanor, all unblinking eye contact and stylish outfits, draws in Dre, and the seriesÔÇÖ most compelling and intimate scenes occur when Eva works to break Dre down.

Over two sessions in a secluded room, Dre allows Eva to question her on what draws her to NiÔÇÖJah, her sisterhood with Marissa, and the violence sheÔÇÖs been committing over the past two years. Ake shoots this ÔÇ£counselingÔÇØ session like an interrogation, with close-ups on each womanÔÇÖs face and lighting that illuminates their shifting expressions, the editing switching back and forth between the womenÔÇÖs rapid-fire dialogue to track their maneuvers for the upper hand. This dynamic resembles the head rush of euphoria that comes from a fast friendship: the secrets that tumble out during a sleepover, whispered at night in the dark and traded like currency, objects to be valued and cherished. ThereÔÇÖs certainly an undercurrent of menace, since Eva wants to collect Dre into her sect. Yet Dre is more forthcoming with Eva than anyone else in the series. When she grins and says of her killing spree, ÔÇ£I really liked it. It made me happy,ÔÇØ itÔÇÖs the most self-aware moment she exhibits over seven episodes. This is a confession, and it comes via the first relationship that demonstrates both acceptance and challenge since Marissa. Around her late friend, Dre was a sycophant and hanger-on, spying on her sexual encounters, kissing her self-harm wounds, and sabotaging her romances. When Eva ends her second therapy session with Dre with a kiss, itÔÇÖs that Dre and Marissa dynamic flipped on its head ÔÇö Dre the object of desire, Dre being asked to stay, Dre the person someone wants to befriend.

If the spectrum that Swarm establishes is, at one end, Dre and Marissa as a genuine-if-lopsided friendship, and at the other, Dre and NiÔÇÖJah as an attachment that exists only in DreÔÇÖs imagination, then Eva exists in a sinister in-between. The disclosures she coaxes out of Dre are the kind of truths that could establish a meaningful connection, and Swarm suggests sheÔÇÖs done the same with the cultÔÇÖs other members. As obsessed as Dre is with NiÔÇÖJah, so too are women like Cricket with Eva. ThatÔÇÖs all messy, intriguing stuff, and Swarm feels boldest when it wonders when person-to-person devotion becomes abstract glorification, and what inner mechanics inspire someone to give themselves over to another. When the show slows down enough to put Dre back on her heels and gives her a frenemy in Eva, someone with whom she can parry and spar, it contextualizes how female companionship can be amplified into something more dangerous, dueling longings for consumption and recognition.

By separating Dre from one hive and dropping her into the orbit of another queen, Swarm sharpens its conflation of love and family with control and coercion. ItÔÇÖs too bad, then, that the series abandons the commune so quickly to put Dre back on fury road, wielding sledgehammers, knives, and lies to make her way closer and closer to NiÔÇÖJah ÔÇö and further and further away from the place where her motivations felt most clear. Swarm should have let her stay a while.