This article originally appeared in the Dinner Party newsletter. Sign up here to get it every weeknight.

Warning: All spoilers all the time below.

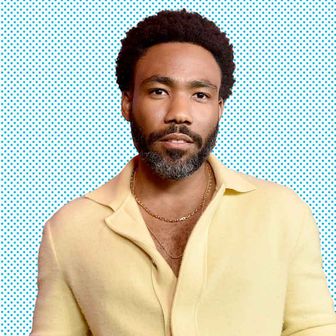

Amazon’s new thriller, Swarm, which sees Dominique Fishback playing Dre, a Beyoncé-like pop star’s stan turned serial killer is quite … a lot. Co-created by Donald Glover and Atlanta writer Janine Nabers, Swarm captures the same eerie, provocative spirit of that previous series, featuring moments — like a sex scene between Chloe Bailey and Damson Idris in the first episode and a cherry-pie-eating moment after Dre’s first kill — that got all the girls buzzing. That sex scene between Bailey and Idris was just the first can of worms for the reactionary responses that verged on outright sexism. The noise has been pretty deafening, with some viewers arguing over sexual purity and others claiming that the show continues Glover’s trend of not totally understanding how to craft Black female characters as fully realized people, with still others calling out the show’s handling of stan communities. Not to mention: how difficult it is to portray madness onscreen at all. Vulture film critic Angelica Jade Bastién and culture critic Shamira Ibrahim joined me to parse it all in a mega-roundtable focused on Fishback’s virtuosic performance, the conversations about Chloe Bailey and sexuality, the show’s limited portrayal of the “mad woman” trope, and how the showrunners’ comments conflict with what we see onscreen.

Tirhakah: The discourse around Swarm has gone to just awful places. Like predictably awful places. Once we saw the reaction to the sex shit early in episode one, I was like, Oh, word, this is gonna be bad.

Angelica: Can you unpack people’s reactions?

Shamira: There was a screening that happened, which, first of all, we are never supposed to be tweeting during screenings, but whatever. Twitter was seeing Chloe Bailey’s bare cheeks and Damson Idris breaking it down in the first 20 minutes. And Chloe is in this weird position of visibility now. She’s in her, like, not a girl, not yet a woman phase, where everyone’s publicly consuming her while she’s figuring out her identity. So everything she’s doing is hyperscrutinized. She’s 24, right? Like, she’s allowed to make some missteps.

Tirhakah: She was homeschooled, goddamn it!

Shamira: Yes. That’s the thing. I’m always like, y’all, Chloe’s a homeschooled, Christian kid who just got thick. It makes sense, right? Especially with how she’s like figuring out her sexuality publicly.

Tirhakah: The people who really should be supporting someone figuring their sexuality stuff out in public are the ones who are like shitting on her the most. It’s very confusing, and it adds an extra layer to whatever kind of commentary they’re trying to make in this show about parasocial relationships.

Shamira: Outside of that, I was actually curious about whether or not it was a body double.

Angelica: That’s what I was interested in as well.

Shamira: Chloe expressed recently that it was actually her first time doing a sex scene, and Damson helped her navigate the intimacy of it all and everything — but, you know, I assumed that it was a body double. I feel like people who keep saying, You can just allude to sex ignore the function of sex, not just in film, but in life. Whatever people’s personal, religious beliefs, or experiences with sex are, I’m really not trying to knock that, but how you navigate in sex as a couple indicates a lot. And how you portray that — you don’t have to show people’s actual genitals! — to intimately showcase whether or not they care for each other, whether they actually are being attentive, whether they’re making eye contact with someone, whether they’re actually present. These are all things that you can’t mask once you’re actually bumping uglies. There’s a reason why a lot of therapists will say things like: Hey, the first thing that goes wrong is that your sex life dries up. Because you’ll be dealing with depression or whatever other things that are interfering. It’s usually indicative of other things, not just that your sex is getting bad. Anyway, like, you can ask questions about what is merited on TV. But you can’t dictate for someone that they feel exploited if they haven’t even said they feel exploited. Angelica, what did that scene reflect for you when you saw it?

Angelica: Dre’s — Dominique Fishback’s — function in it. It’s kind of weird that people lose out on the storytelling aspect cuz they’re seeing some ass. Like, come on, y’all. But for me, that was one of the first very obvious times that I’m like, Oh, she’s in love with Marissa. She’s in love with this woman. She’s not interested in him; she’s interested in how close he is to her. I think that’s why she’s looking at him in a very judgmental sort of way. And you can tell what he’s thinking, which is, Oh, she wants this. A very intriguing and rich moment thanks to Dominique Fishback’s performance. There’s a lot her performance is doing that I think helps with the fact that the script is really sloppy, and she does a lot of work to make it feel more cohesive. I thought what she said about Donald Glover directing her very curious, when he told her, “Think of it more like an animal and less like a person.” Reading that, I realize just how good of a performance Fishback is doing. It’s terrible direction. You’re confusing her. Glover said, “I kept telling her, you’re not regular people. You don’t have to find the humanity in your character. That’s the audience’s job.” Donald Glover is not a good storyteller. He happened upon good things, he’s done good things. But I think his ethos as a storyteller is completely opposed to how I look at storytelling. A major problem I kept bumping into: The camerawork wants you to gawk at her rather than understand her. It’s only cohesive because of what Fishback is doing. The showrunners — who I wish would shut up sometimes — are also obsessed with the representational aspects.

Like, oh, we’re getting parity with white women who get to be crazy onscreen. Shamira and I talked about this, and she made the point that the reason why we don’t see Black women characters like this is because of the carceral weight and effects that end up bearing down on a Black woman would immediately put you in a life-or-death situation. It’s playing around and wants to be disconnected from reality to skirt by the criticism of the fact that it feels disembodied from Black women. It’s a Black woman’s story, but it’s not really about Black women, if that makes sense.

Tirhakah: Can I push you on that a little bit? What is it about? I do think it’s really hard to take in the discourse, and like you said, I really wish these niggas would just shut the fuck up.

Shamira: They need to stop talking.

Tirhakah: It doesn’t feel like she’s totally an animal. It doesn’t feel like she’s disconnected from her emotions.

Angelica: No, she isn’t. For me it’s also that people talking about anger doesn’t make sense. No. This is a lonely, hurt person. It doesn’t read like rage so much as like intense emotional overwhelm, and a feeling of loss and loneliness.

Shamira: I think part of that is a function of them trying to do too many things, right? They’re trying to do a character study, layer social commentary, and, if you wanna call a black woman serial killer “representation” — all of those things at the same time, that’s a burden. Tryna do all three in seven tightly shot episodes is a heavy load to carry. The social-media standom commentary falls flat. It goes nowhere completely. You don’t necessarily wanna empathize with someone’s killing spree to understand the sequence of actions. But, this cascade, that overwhelm, this is what she knows, right? That final murder is different from the first murder. You see her crying, right? That’s a clear emotional spectrum of someone who is grappling with something very intense. That doesn’t mean that there shouldn’t be any accountability or she should be exonerated for all her actions. It just means that there’s a clear evolution. And what Dominique did was make us curious to all those circumstances she didn’t even fucking know herself.

Angelica: That’s a good actor to be able to conjure what you yourself are actually confused about. That final murder is the most intimate because she uses blunt-force trauma or guns every other time. This time, like she’s straddling this woman, strangling her, crying, can barely look at her. She’s looking more past the camera’s eye line. It’s actually very smart visual choices. I think what’s frustrating me as a critic, and I’m glad I get to talk to y’all while I’m working on this review, is that the way Janine Nabers and Donald Glover have talked about things. They’re doing their own show a disservice.

Tirhakah: Yes! They’re betraying it!

Angelica: I think it’s muddling my thoughts on it. I said earlier, oh, I don’t think it’s about Black women. But actually I think that episode six is all about Black women falling through the cracks. That scene with the social worker and foster care, the show suddenly gets onto the land you want it to be on, which is like dealing very specifically with what were the cultural, personal, and historical factors that led Dre to make these decisions. And then you also get someone recognizing Dre’s humanity and, in a way, sort of protecting her history that people are now trying to dig into. There’s something fascinating and prickly and intriguing about that.

And the people behind this show; I think this is a good example of how a lot of times artists don’t even fully realize what they’re doing. So when you interview them, you’re thinking you’re gonna get all these explanations. But sometimes people don’t really know what they’re creating. That’s what people are kind of bumping into. The way Dominique Fishback is acting shows that she is seeing humanity and dynamics that are pretty complex. And I think the creators of this show see it in a very simplistic fashion, which you can see when they talk about the whole representation, which is the wild aspect of a Black female serial killer. Which I’m like, this is not the parody I was asking for.

Shamira: I found the scene where she was at that NXIVM cult thrilling. I was like, Billie Eilish, okay!

Tirhakah: She’s got some layers to her!

Angelica: It was smart in terms of rounding out how the show is mulling through femininity. We see Dre in the context of a very specific kind of white woman. The scene where Billie Eilish’s character, Eva, queen of this cult, is snapping her fingers? The show is really smart when it takes a step back narratively, and then lets the actors fill in the blanks, which you get a lot in these close-ups.

Shamira: The subtle expressions: the gentle grin that rests on Billie’s face while Dominique is slowly being broken down. She slowly goes from Kayla to Dre. She reveals her violence, but there’s even other one-liners, where she talks about how she liked the violence when she finally unleashed it. That was striking. The small allusions to the violence and her biological family, which she initially calls milk, becomes blood. Eva goes, “Do you pray?” Dre answers, “I used to but I stopped.” Eva asks why. And it’s, “Oh, because I realized that God is just my voice echoing.”

Tirhakah: A fucking bar!

Shamira: But it’s frustrating because, if you really played into that, it’d be dope, but they’re hesitant. This is a woman who’s playing with emotional extremes. And they’re so reluctant to acknowledge it. They’re reluctant to assign an -ism to it. And I’m not saying they have to give her one, but the show wants to call stan culture an illness and all these other things. They tell us she went to a psychiatrist, psychologist, and all that other stuff. You don’t go to somebody without them saying, “You got something, here’s a bunch of pills.” Especially just going to a psychiatrist, they tell you something after like 15 minutes.

Tirhakah: What do y’all make of it as one sort of villain origin story — and then, what does it have to say about madness and mania?

Angelica: That’s a very weird way to describe this show. I never thought of her as a villain.

Shamira: It’s a tragedy.

Angelica: She’s a tragedy. Someone who’s been deeply victimized her entire life and her way of gaining control and stability for her is violence and delusion. It’s an alienating use of language to describe the character like that. I just don’t see it as a villain origin story. It’s a tragedy that you know is not gonna have a great conclusion. And you’re going along with this ride with her hoping that — you know, not saying I wanted her to get off scot-free or whatever. But even with a character who makes such fucked-up decisions, you’re hoping that she gains something. That there’s something at the end for her. The ending of the show is funny to me because it ends where pretty much every mad-woman story ends: either dead or she’s consumed entirely by delusion. And we are no longer in reality, we’re in whatever dream space she exists in.

Tirhakah: So you’re saying that Ni’jah/Beyoncé didn’t caress Dre in her bosom?

Angelica: Right, what was that!?

Shamira: I wanna know if that CGI was bad on purpose. If we wanna continue that through-line of it being like a Black story, one thing that’s constant is knowing inherently no matter how much we wish for an intervention, we know it’s not going to arise. There’s not going to be a resource that comes there for her. There’s not going to be someone that says, “Yes, you need help, you need to be stopped — you need to be sent to a facility so that you can be taken care of and taught how to have proper coping mechanisms.” That’s never coming. And you know that all that’s going to come is that she’s going to be locked up at a facility for the rest of her life.

Tirhakah: How does it stack up against other portrayals of madness, and what are some things that spoke to you on that level?

Angelica: Madness in cinema is the terrain of white women because this culture loves to watch white women unravel. The beats of the “mad woman” trope have always been tied to whiteness in a way that has always been an interesting but alienating study for me. But I think Dominique Fishback creates a clarity in her character, especially in close-ups when the show is just like, You do your thing — you see a level of complication and interiority and rawness and deep yearning within the character. I don’t think it’s novel beyond her being a Black woman, though. If you watch enough movies about mad women, you notice certain currents. I can name several movies with mad women, from Sunset Boulevard to Possession to something as wild as In This Our Life; they all home in to the same ending, which is both planting you within the mind of the mad woman and suddenly you’re outside of reality. You don’t know what has happened to her, but you know her emotional truth.

Shamira: There are so many moments where you are asked to fill in the universe. The Beyoncé knockoff — I was like, Oh, wait, they re-created the elevator incident. What did it actually serve narratively? Was there an actual propulsion of plot with that? No, it was just shocking enough to say that they had the audacity to do it, because what other show would do that except for like Law and Order: SVU? One thing I’m noticing because of the lack of precision, people using terms like madness and anger interchangeably or madness and rage interchangeably. There’s more conversation around needing more Black women’s rage onscreen, or women’s anger onscreen. Not to say that I’m opposed to that, but a lot of our marquee performers, our marquee thespians, are known for their ability to home in on rage. That’s their pocket. Viola Davis, you know, Angela Bassett. I can think of recent movies like Nanny by Nikyatu; that film is constructed around a woman’s quiet rage and resentment that bubbles over and in some moments descends into madness. These are things that are explored. This is not a novel, unprecedented concept.

Angelica: What Swarm is making me ask some questions about is what we expect when it comes to portraying mental illness onscreen. What do we need from these characters that feels emotionally realized, but also experiments enough that they aren’t one-to-one representations of reality? Maybe my interest in the carceral effects on Black women who deal with mental illness is expecting a level of reality from a show that has a very tricky relationship with it.

Shamira: Due to the limitations of the script, Fishback struggled with this role and had to focus on movement. She stepped up to that challenge.

Angelica: I noticed her movements too; they’re jarring. It’s a smart approach to reflecting on the fact that this person is emotionally stilted and has a mess of things that they don’t know how to navigate and it is rendered, and having a physicality that does not abide by the certain social etiquette we’ve come to believe, especially her relationship with food, puts that under a spotlight.

Tirhakah: When you say consumption, we’re talking about how class and our personal understandings of greed play out in our behavior, our patterns. For Dre, it’s overconsumption of shitty foods. What is that connection?

Shamira: She’s so restricted with everything else. Not drinking, not smoking. But in the words of the goddess Ice Spice, when she in ha mood, whether violent or sexual, she’s intense. She went to the club and she got that coke and white man and said, We goin’ to town.

Tirhakah: She said, I’m doing everything! No one’s gonna make fun of me being a virgin again, it’s not happening!

Shamira: She got out that freak-’em dress and she was like, I’m that girl.

Tirhakah: So I have to get y’all thoughts about this on wax: There’s a widespread theory centering on the idea that Dre killed Marissa. Where do y’all stand on it?

Shamira: Anti! Anti! I’ve seen it. I’ve seen threads on color theory. I’ve seen it all. I don’t think so. First of all, they went outta their way to indicate that Marissa had a self-harm habit. Even though they used that as another opportunity to showcase Dre’s psychosexual relationship with Marissa. I mean, I love my friends. I don’t be kissing their scars.

Angelica: I’ve never kissed a friend’s scars.

Tirhakah: A friend? No.

Shamira: A sister? Even less. But yeah, the self-harm thing serves as a trigger for Dre to never wanna let go of her phone. People are forgetting that. There’s a reason why she’s so attached to her phone. It’s not just standom. It’s because she needs to stay attached to Marissa because the last thing she did was ignore Marissa. And she feels immense guilt about that. She feels responsible for this death, so she wants to protect and defend her memory.

Tirhakah: Okay, but how responsible is she? She has guilt and shame. Could it be from her being the one who actually killed Marissa?

Shamira: So are we saying that she, like, completely made up being in that nigga’s bed? She time-traveled? It doesn’t add up. They think that she made up or dreamed about it. Did she dream going to the club? Did she dream Marissa leaving? Did she dream the video that Marissa sent her? At what point is it that she actually went back and killed her?

Angelica: People thinking she killed Marissa is a cruel reading of her character. It misunderstands her emotional state in a lot of ways. To me, Dre reads as the person who really loved Marissa. She was supposed to be there for her and help her in her darkest moment, but because she was trying to do her own thing, she missed her at her lowest point. In my mind, I was like, Oh, she probably thinks by saving her, it could have opened up their relationship in a new way. And so she’s grieving a multitude of losses at once. I don’t think she killed her because the whole point is the loss of Marissa is what creates the final crack.

Shamira: She’s like catatonic for days on end after that death. She clearly stops paying bills. And as we’ve already discussed, after every other death, she goes on a binge. She indulges. But she didn’t revel in Marissa’s death. This is an actual moment of grief for her.

Tirhakah: Yeah, until it’s not, and she becomes fucking Jason Voorhees and murders everyone.

Shamira: You really have to suspend disbelief, ’cause if you don’t, then you’re like, All right, well, this bitch would’ve been arrested by episode three. Like, did she start just like Googling how to murder?

Tirhakah: She’s really good at it. Like, she’s really fucking good.

Angelica: I did laugh when she ran over Billie Eilish after hitting her with the car.

Shamira: There were legit bits of laugh-out-loud humor. Playing those comedic beats even in the middle of abject violence. That maniacal laugh that she had while she was killing all the white bitches!? And poor Paris “Halsey” Jackson. That diner scene was just a master class in nonverbal expression. Watching Dre’s face just, like, twitch while Paris was talking about, You know I’m Black, right?

Tirhakah: That part where she murders that YouTuber in his house and the last thing that he says after she shows him the anti-Ni’jah tweets is: “Nigga, Twitter?” And then she just beat the shit outta him. Like, imagine those were your last words. “Nigga, Twitter?”

Angelica: Swarm is a good example about how critics and audiences alike really struggle with nuance. We don’t know how to reckon with work that is complicated and messy and lacks certain elegance. We get a little weird because the conversation around the fact that, oh, but there’s Black women involved in this show — I don’t even know what to say to y’all at this point. What does that have to do with criticism?

Shamira: I think the show doesn’t land the point it wants to land, for all of the attempted subversiveness and shock value of the promotion. It just doesn’t execute. But what it does execute is the actual roles they cast really well. Those actual performances lifted the show.

More From This Series

- 15 Emmy-Worthy Performances That Shouldn’t Be Overlooked

- Let’s Talk About the Black Madwoman in Swarm

- Swarm’s Heather Simms Thinks Detective Greene Is Still Looking for Dre