You loved the movie and you want more. The studio loves money, and they want more too. That’s how sequels come into existence — and this year we’re being bombarded by them, with new Sonic the Hedgehog and Fantastic Beasts installments already in theaters, and Top Gun 2, Hocus Pocus 2, another Jurassic World, another Downton Abbey, more Minions, more Thor, even more Marvel and D.C., and Avatar 2, among others, still to come. It’s easy to feel cynical about sequels, since they often seem like cash-grab retreads of their inspiration. But to reflexively dismiss follow-up films is to disregard the enormous potential they hold — in the right hands they can deepen the relationship we have with characters and the worlds they populate.

There’s an art to making a genuinely good sequel. Filmmakers must work within certain parameters to ensure consistency with the original entry, but the best ones treat existing hits (or flops, for that matter) as material that they can reinterpret, comment upon, or completely transform — and that’s when the continuation starts to become fascinating. For the purposes of this list, we’ve defined a “sequel” as any follow-up installment to an existing property. There are straightforward sequels; legacy sequels, featuring an actor from a long-ago hit returning to engage with a new generation in the film’s universe; stealth remakes, where a new filmmaker departs from the original work and changes the genre (from, say, a haunted-house film to a war film), tone (from poker-faced to borderline parodic), or even the level of self awareness (to the point of contemplating what it was about the original that inspired sequels to it in the first place); and interquels and prequels and titles you may well consider to be spin-offs, because what are these if not subcategories of sequels?

What we looked for from each film was the nature of its sequelness, or how much a movie builds off its audience’s preexisting relationship to a story or world. (In that sense, movie sequels to TV series counted.) Our single rule: Only one film per franchise could appear on the list — so the Broccoli family’s Bond world and the MCU get just one entry apiece, while the Batmans and Spider-Mans, having had multiple distinct incarnations, were eligible for repeat appearances. The final choices showcase sequels that introduce new ideas and behaviors and filmmakers who set precedent for not only their own franchises but for the genre worlds beyond them. But more often than not, we rewarded pure pleasure. The sequels that rank highest are those that managed to distract us from the inevitable commercialism in Hollywood and our cynicism about the future of moviegoing. They remind us that more is more can indeed be a righteous course.

Note: This list has been updated (and will continue to be updated) to account for new releases that warrant inclusion. To see where the most recent addition, Top Gun: Maverick, falls on the ranking, jump ahead.

.

(Skip to No. 1 on the list.)

102.

Happy Feet Two (George Miller, 2011)

Don’t let the singing penguins or the puffin who can’t stop blowing snot bubbles fool you: This is a movie from George Miller, the fourth sequel he directed and the last film he made before he set his sights on Mad Max: Fury Road. Happy Feet Two isn’t a perfect film; its narrative is muddled by disjointed scenes in the first half, and, as talented as he was, both of Robin Williams’s race-bent voice roles induce cringe. But as the sequel to a popular, original ’00s animated children’s film, it speaks to the trends that defined its era: The puns are relentless. (“Good-bye, krill world.”) The celebrity casting is dizzying. (Brad Pitt sells his role as Will the Krill, who wants to kill his way up the food chain, which is more than I’ll say about his scene partner, Matt Damon.) The soundtrack is built almost entirely off pop-music covers. (Hank Azaria does “Dragostea Din Tei”!)

For all that and more, Happy Feet Two was punished. Like a flightless bird, it infamously flopped at the box office. When the film works, though, it really sings. The crass jokes snuck in between touching father-son bonding moments hit all the right notes. The animation — specifically the vast, empty Antarctic backdrops — are worth the many, many pennies spent and lost. The climate-change message sorta holds up; this is a movie about preventing an ecological apocalypse in Antarctica, after all. You have to wonder: Would Miller have been so energized to make Fury Road had Happy Feet Two not flopped? Let’s not think about it too much. —Eric Vilas-Boas

101.

Devil’s Rejects (Rob Zombie, 2005)

Rob Zombie branched off from music into filmmaking with 2003’s House of 1000 Corpses — an aggressively violent homage to ’70s horror movies (from classics to grindhouse cheapies) that earned generally negative reviews. Undeterred, Zombie doubled down for this sequel, which resumes the exploits of the kill-happy Firefly family. The film showcases Zombie’s growing confidence as a filmmaker — both in the way he cements his violent western style and in his philosophical themes built into a story of attempts at revenge that escalates into a cycle of cruelty that threatens to engulf everyone in the Fireflys’ orbit (possibly the entire state of Texas). Zombie packs the film with homages and cameos and with a supporting cast that includes everyone from comedian Brian Posehn to cult star Mary Woronov, but he refashions the existing story universe to create a distinctly original vision that made even those who dismissed his first film take notice. —Keith Phipps

100.

Mamma Mia! Here We Go Again (Ol Parker, 2018)

The first installment of Mamma Mia! is its own accomplishment, not least for featuring Meryl Streep doing the splits in midair in a pair of overalls. But Mamma Mia! Here We Go Again is a whole universe unto itself, so important to the international cinematic canon that this is now the third time I am writing about it for this very website in as many years. This is because MM!HWGA is about nothing less than the Technicolor insanity of life itself. It crams the plot, character count, and themes of at least 12 films into one. It is about how sometimes you are Meryl Streep doing the splits in midair in a pair of overalls, and sometimes you are Meryl Streep coming back as a ghost at your granddaughter’s baptism. It is about being slutty in Europe. It is about death. It is about time travel. It is about Cher. It is about the Mother Wound and healing intergenerational trauma. It is about aging; it is about making fertility decisions. It is about having good beach hair. It is about the challenges of balancing entrepreneurship and long-distance relationships. It is about shawls. It is about friendship over decades. It is about how it is inherently funny to see old men in glittery spandex. It is about forgiveness and horses. It’s about liminality. It is about unpredictable weather patterns in the Mediterranean. It is about temporarily shaking off the dark, powerful specter of Lars von Trier’s filmography. Most of all, it is about egolessness and joy, about how sometimes life throws you a bone and somebody pays you actual money to get really tan and drunk with Christine Baranski and Pierce Brosnan on a fictional Greek beach again. —Rachel Handler

99.

The Matrix Reloaded (The Wachowskis, 2003)

A little over halfway through the Wachowski sisters’ follow-up to their game-changing The Matrix is a freeway chase of glorious sensibilities. Cars flip like gymnasts and crack apart as if made of glass. The chase reaches operatic heights when Trinity gets on a motorcycle with the character known as the Keymaker holding on for dear life. The thumping score by Don Davis brings us to the apotheosis of cinematic rapture. Of course The Matrix Reloaded continues the journey from the first movie, bringing back the main crew along with some new additions, all fighting the machines in hopes of protecting the city of Zion. The film can get messy, enamored with its philosophy. But at its best it’s a love story revolving not just around the tender-hearted savior figure Neo, but around community and the worth of humanity itself. The Matrix Reloaded is what happens when directors get a larger palette with which to play. It’s bombastic and easy to love, keeping audiences and its beloved characters on the precipice of disaster. —Angelica Jade Bastién

98.

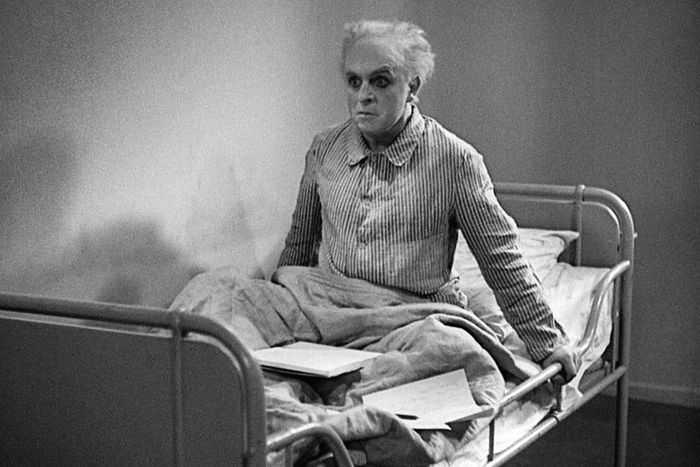

The Vampire’s Coffin (Fernando Méndez, 1958)

1957’s El Vampiro was one of the signature films of the Mexican horror boom of the 1960s, and it was so successful that director Fernando Mendez and producer Abel Salazar swiftly produced this sequel. Also returning was German Robles, who had made such a charismatic and elegant monster in the first film; his is still one of the all-time great portrayals of a vampire onscreen. You can see that this one was a quickie. The first film was drenched in creepy rural atmosphere, while this one is set mostly in a curiously empty, blank-walled hospital and, well, a basement. But it’s loads of fun in its own right. It has an unhinged sense of humor, for starters — as if the filmmakers are constantly winking at us not to take this whole sequel thing too seriously. And not unlike the first film, The Vampire’s Coffin is enormously creative in its use of low-budget effects. Watching these movies, you realize that an effect need not look realistic to send shivers up your spine. It’s wonderful what Mendez could do through just the simplest of cuts. —Bilge Ebiri

97.

Abbott and Costello Meet the Mummy (Charles Lamont, 1955)

Brand synergy. Crossover events. We think we’re at a boiling point for this stuff now, but Disney/Fox/Marvel/Star Wars/The Simpsons/Spider-Man has nothing on the hottest collab of the mid-century: Universal Classic Monsters x Abbott and Costello. Between 1941 and 1955, Bud Abbott and Lou Costello starred in six monster mash-ups for Universal Studios — getting wound up in hijinks opposite the horror greats: Bela Lugosi’s Dracula and Lon Chaney Jr.’s Wolf Man (in, oddly enough, Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein); and Boris Karloff (not as Frankenstein but Abbott and Costello Meet Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde). Their vaudevillian slapstick translated well into the heightened worlds of horror — the nonsensical nature of both complementing each other. The duo’s final creature feature was Abbott and Costello Meet the Mummy, in which they get themselves mixed up in a plot to steal sacred treasure from an Egyptian tomb. What the two blabbering goofballs lack in pith they make up for in pith helmets as they use ancient archaeological ruins as a playground for gags; some comedic business about “taking your pick” between a shovel and a pickax is a “Who’s on First?”-style libretto of misunderstanding.

The upside of an Abbott and Costello film at this late stage of their partnership is that they’ve worn into the rhythms of their banter like they share one mind. The downside is that, by the mid-50s, their ’30s-vaudeville-style routines were beginning to gather dust and grow a little creaky — fitting for a mummy movie. Here, they weren’t acting against Chaney or Karloff but rather their studio stunt double Eddie Parker. Not to mention the Orientalism of it all. This sequel was the end of more than one era; it was the penultimate Universal Classic Monsters film (a Creature from the Black Lagoon threequel came out in 1956). With Mummy, Abbott and Costello landed the punch line. —Rebecca Alter

96.

The Souvenir: Part II (Joanna Hogg, 2021)

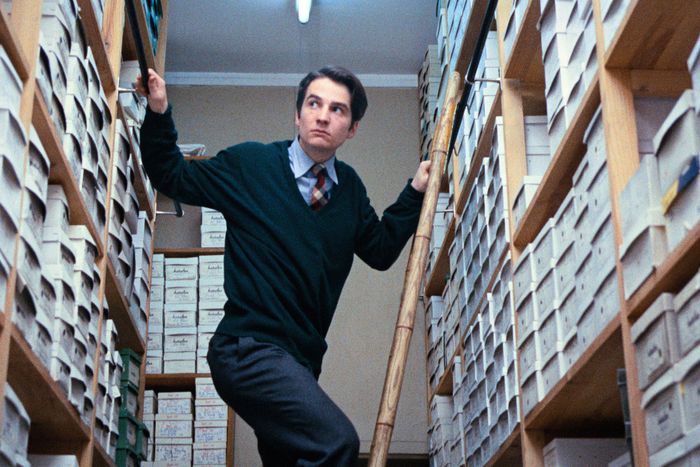

Did The Souvenir really need a follow-up? Joanna Hogg’s art-house memory piece ended pretty definitively with the death of one half of its central couple. There’s a reason they didn’t make a sequel to Titanic, you know? And yet, once Part II hit screens, the reason for its existence became self-evident. The Souvenir was Hogg turning her old love affair into art; its sequel sees her stand-in Julie (Honor Swinton Byrne) stumbling through her own attempts to adapt the story to film. It is, essentially, a movie about how hard it was to make The Souvenir, and Hogg offers an unsparing — but not unkind — view of her youthful missteps. (Pressed to explain her creative decisions to her cast and crew, Julie can only offer a feeble “That’s how it happened.”) Part II shares a time-capsule tactility with its predecessor, and it has the benefit of being funnier — especially when Richard Ayoade pops up as a filmmaker with the bitchiest perm in London. The film’s slyly triumphant ending makes it clear how far Julie has come. —Nate Jones

95.

The Purge: Anarchy (James DeMonaco, 2014)

Set in a near future in which a fascistic American government ruled by the “New Founding Fathers of America” makes all crime legal for one night a year, the 2013 film The Purge introduced an irresistible premise. Focusing on a single family trapped in their (supposedly) well-protected home, it’s also, at heart, a dressed-up home invasion thriller. Which raised a question: What was going on in the rest of the world? The Purge: Anarchy — the first sequel in what’s become a five-film (and counting) franchise that’s also spun off a TV series — answered with a handful of characters who find themselves stuck in the wilds of Los Angeles when Purge Night begins. Written and directed, like the first film, by James DeMonaco, The Purge: Anarchy retains the original’s brutality while offering glimpses of a larger world filled with Purge diehards, resistance movements, and general nutcases, while opening the door for the even more explicitly political sequels that followed. —K.P.

94.

How to Train Your Dragon 2 (Dean DeBlois, 2014)

The thing about animated sequels (whether set in a realistic Antarctica or a fictional Viking village) is that the development, artwork, and effects required to bring back their worlds require gargantuan amounts of time. (Rendering one frame of animation takes about one day, and there are 24 frames per second; the math gets wild!) Creators risk years of work on the belief that the audience of the first animated film has not aged out of interest by the time a second or third or fourth arrives. Somehow, the How to Train Your Dragon franchise never felt like it was flattening itself for a younger audience or overreaching for an older one. Instead, How to Train Your Dragon 2, the trilogy’s middle entry, is bold in its storytelling, with director and writer Dean DeBlois trusting fans could follow a plot about compromised dreams and the threat of forever war. The result is thrillingly imaginative both visually (so many new dragon designs) and thematically, with a particularly poignant good-bye to Gerard Butler’s Viking chieftain Stoick the Vast that unfurls a path forward for Jay Baruchel’s Hiccup, setting aside this as one of DreamWorks Animation’s best. —Roxana Hadadi

93.

Universal Soldier: Day of Reckoning (John Hyams, 2012)

The original Universal Soldier, a pretty schlocky 1992 Jean Claude Van Damme-Dolph Lundgren team-up that was directed by future disasteur Roland Emmerich, initially gave rise to a series of fly-by-night sequels that are all but forgotten today. Years later, however, director John Hyams got his hands on the franchise and created a couple of surreal, low-budget action thrillers that don’t seem to have anything to do with the original films, aside from the presence of the aforementioned stars. This is the second of Hyams’s efforts, and it’s probably the closest thing we’ll ever get to a Michael Haneke-David Lynch-Rowdy Herrington collaboration. The great Scott Adkins plays a grieving man on a Heart of Darkness–style journey to find super soldier-turned-terrorist Luc Devereaux (Van Damme), who now seems to be more eternal spirit of evil than man. Gorgeous, perplexing, and — when it bursts into violence — heart-stoppingly intense, with fight scenes that are choreographed and filmed with unnatural fluidity. This might be the only case in history of a franchise that was utterly moribund right from the get-go and yet somehow managed to produce a masterpiece with its … [checks notes, does a series of quick calculations] … sixth installment? —B.E.

92.

Spy Kids 2: Island of Lost Dreams (Robert Rodriguez, 2002)

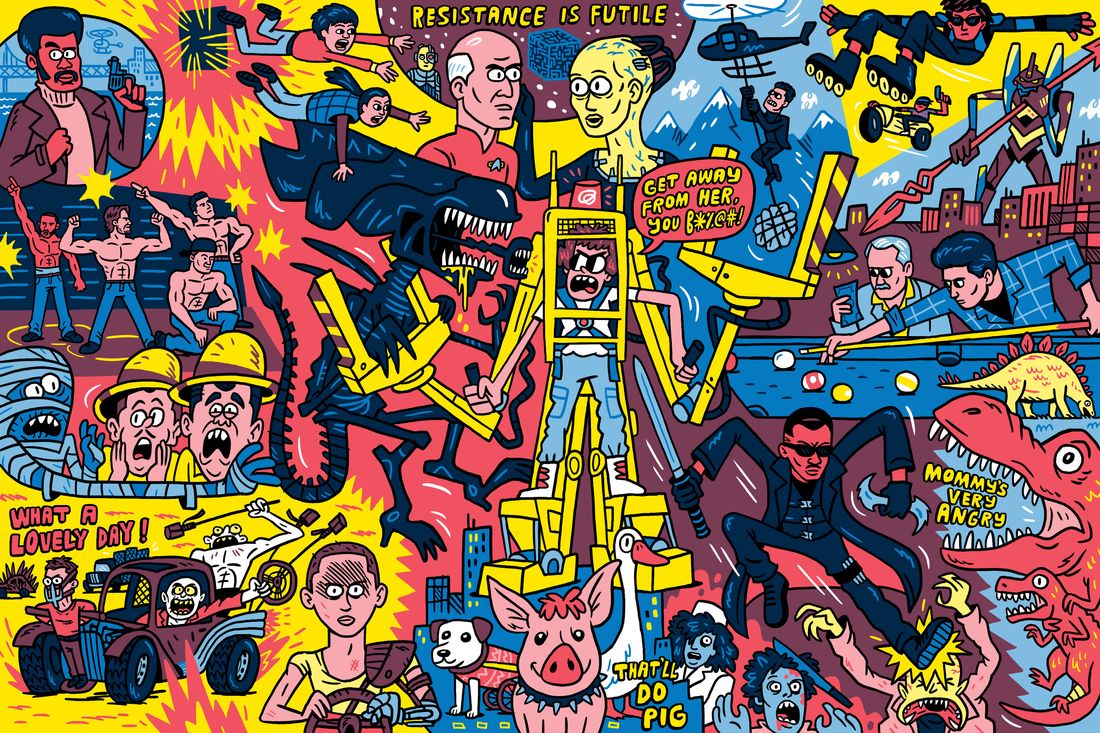

The English language is too feeble to contain a word that captures the aesthetic overload of watching one of Robert Rodriguez’s Spy Kids films. The closest thing that comes to mind is an amalgam (like the CGI-fusion creatures of Spy Kids 2: Island of Lost Dreams): hyperfake. Hyper as in hyperreal but also hyperactivity disorder. These movies look and move like they were made on a pixie-dust bender — with writer-director Robert speaking in a whistle tone that only Y2K kids can decipher. (Babe: Pig in the City is another fine example of “hyperfakecore.”) The first Spy Kids (2001) still had some tether to things like story structure, character arcs, emotional variation, and pacing, but the maximalist Spy Kids 2 just takes the fantasy-fulfillment angle of that story and runs with it. Every shot has something wild rendered in crisp, colorful, hyperfake CG fueled by Looney Tunes–paced slapstick: A gravitationally impossible theme park run by Bill Paxton in a cowboy hat (the character’s name? Dinky Winks). Pigtails that spin like helicopters. A top-secret tree house with Danny Trejo in it. Two dads fighting as the kids yell, “Kick him in the butt!” so the dads literally kick each other in the butt. A presidential banquet where all the food is buttered noodles. With Island of Lost Dreams, Rodriguez took his prodigious genre abilities and applied them to making a movie that speaks to its audience members on their level like little else. “Do you think God stays in heaven because he, too, lives in fear of what he’s created?” And do you think he fears Rodriguez specifically? —R.A.

91.

Bride of Chucky (Don Mancini, 1998)

Bride of Chucky marks a turning point in the Child’s Play franchise that introduced the murderous kids’ doll inhabited by the soul of a serial killer voiced by Brad Dourif. No longer playing it straight, Don Mancini’s Bride of Chucky is meta and silly. At a lean, mean 89 minutes, Bride is electric from the start, with Tiffany Valentine (played by the GOAT Jennifer Tilly) playing the former lover and accomplice to the serial killer that became the Chucky we know and love. Tiffany has the unfortunate fate of being killed by Chucky, her soul transferred into a doll herself, leading to some intense domestic squabbles that come with a body count. Bride of Chucky is gleefully profane, directed with the sort of orgasmic joyfulness that I want from a horror sequel. “What would Martha Stewart say?” Chucky asks. “Fuck Martha Stewart!” Tiffany replies. (Its queer excess set the stage for Seed of Chucky’s nonbinary child, referenced in the Syfy television series that dropped last year.) There have been self-referential horror films before and after it, but Bride of Chucky is a smart example of how to inject new life into an ailing franchise: Lean in and the camp will come to define the franchise. —A.J.B.

90.

A Goofy Movie (Kevin Lima, 1995)

A Goofy Movie — technically a spinoff to the TV series Goof Troop, but in our taxonomic worldview a sequel nonetheless — is a kind of kid film that no longer exists, especially when it comes to Disney. A road trip turns into a misadventure that bonds the single father Goofy and his son, Max, who have a tense relationship because of various unspoken fears on both sides. A Goofy Movie is direct in its emotional resonance and gentle in its messaging, opting against grand statements about the world in favor of a simple, loving story between a single parent and his only child. The voice work is gorgeous and elastic. The animation is lived in and textured, making me miss the days of hand-drawn work. And A Goofy Movie is Black cinema. Every Black kid I knew — my family included — viewed the story as that of a Black family, because when you love pop culture you learn to find yourself in unexpected places. (Among others, in the vocal stylings of Tevin Campbell as Powerline.) It’s why audiences turn to sequels with hunger: They allow us to be enveloped once more in an expanding world we believed we already knew, simultaneously confirming and introducing ideas for nothing more than contentment. —A.J.B.

89.

Saw III (Darren Lynn Bousman, 2006)

How many sequels begin with the inevitable death of its main villain? Though director Darren Lynn Bousman and screenwriter Leigh Whannell knew other entries would follow, they framed Saw III around a brazen conceit: Dying from an incurable disease, Jigsaw clings to life with the same desperation as his many victims. On his orders, his psychotic protégé, Amanda, kidnaps Dr. Lynn Denlon to keep him alive while his latest game unfolds: Jeff, a father consumed by regret, must traverse Jigsaw’s maze, passing tests with people involved in his son’s death. Through frenetic flashbacks it builds out backstories to Jigsaw and other characters, and features head-spinning twists. Elaborate kills are a mark of the franchise, and Saw III possesses some of the best, most gnarly of them. (For instance, “The Rack,” which bolted a man in a crucified position to a machine meant to twist every limb off his body. Its distorted sound design still haunts my spine.) But most importantly, the installment builds on the ideas of moral absolutism introduced by its predecessors. Jigsaw is a heinous murderer, but he lives and plays by a certain set of rules. Toxic grief, on the other hand, consumes Amanda and Jeff to the point of bending their morals. Copycat horror flicks followed — You’re Next, Escape Room, Don’t Breathe — but few effectively wrestled with the question Saw poses: Who deserves forgiveness and who is beyond it? —Robert Daniels

88.

The Avengers (Joss Whedon, 2012)

The Avengers is one of the most sheerly satisfying comic-book blockbusters — a pure entertainment machine that brought together heroes and storylines separately established in films about Iron Man, Thor, the Incredible Hulk, and Captain America, plus several other heroes, all banding together in New York City to protect Earth from an extradimensional and extraterrestrial invasion. Written and directed by Buffy the Vampire Slayer showrunner Joss Whedon — one of many once-adored pop storytellers who became He Who Shall Not Be Named following revelations of sordid private conduct — the film also established and cemented the franchise’s default tone, which mixed self-aware, snarky quips with landscape-altering mayhem and bruising fights. The interplay between the key members of the team — especially Cap, Iron Man, and Bruce Banner — is genuinely funny, never more so than when they’re interacting with the franchise’s finest villain/antihero/spoiler, Thor’s trickster brother Loki (Tom Hiddleston). The Avengers is also notable as the final ensemble-driven, “heroes unite” MCU epic that wasn’t somewhat weighed down by self-importance, an obsession with ancient mythology parallels, and audiences’ expectations that the studio should give them something more overwhelming than they got last time. The movie is light on its feet, and not just because some of its characters can fly. —Matt Zoller Seitz

87.

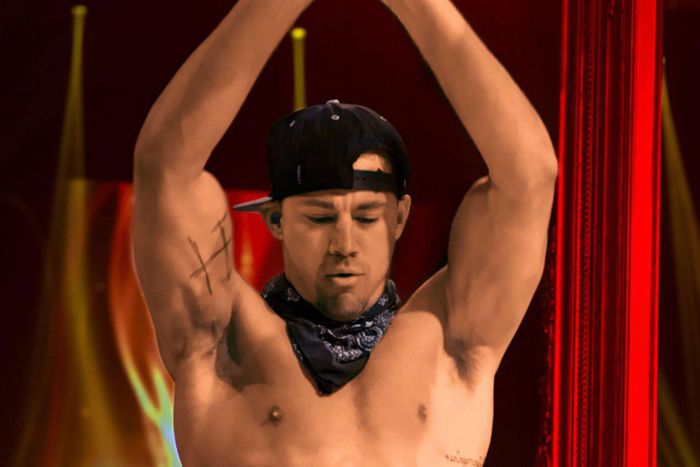

Step Up 3D (Jon M. Chu, 2010)

If the Step Up franchise had only given us Channing Tatum, that in itself would have been a solid achievement. But it also served as the launching pad for Crazy Rich Asians and In the Heights filmmaker Jon M. Chu, who made his directorial debut with 2008’s Step Up 2: The Streets and then two years later would craft the dazzling Step Up 3D. The plot is predictable, with star-crossed lovers from within and without a dance crew named the House of Pirates trying to balance their passion for dance with the demands of family, school, and “real” life. (There’s also a narratively important pair of limited-edition Nikes because consumerism, baby!) But Step Up 3D is thoughtful both in its deployment of returning cast members and in its suggestion that they all continue to exist in a world where dance is a shared language that expresses every kind of human feeling, from jealousy to resentment to love. The film’s concluding World Jam competition between the rival House of Samurai and House of Pirates captures some of Chu’s worst tendencies (e.g. cutting away from the main action for rote reaction shots) but more of his good ones, like how fluidly he guides our perspective toward the dancers’ flipping, contorting, sashaying, and spinning bodies. It takes a lot of gumption to redo a Fred Astaire classic like “I Won’t Dance,” but Step Up 3D pulls that off, too. —R. Hadadi

86.

Predator 2 (Jim and John Thomas, 1990)

Same predator, different jungle. That’s the premise of Predator 2, which takes the extraterrestrial hunter and places him in a future (1997) Los Angeles where various drug cartels have turned the city into a warzone. Despite constantly pissing off his superiors, LAPD officer Mike Harrigan has been tasked with quelling the turf war, but he quickly turns his sights on the mysterious invisible force wiping out gang members one by one. Although Kevin Peter Hall reprises his role as the Predator, albeit with a sleeker design, and co-writers Jim and John Thomas returned to pen the sequel, Predator 2 almost immediately establishes its own identity with an opening shoot-out that embraces the controlled chaos of its urban environment. Director Stephen Hopkins lends a craftsman’s eye to the sequel: He follows Predator director John McTiernan’s lead by emphasizing space but adopts a more manic energy to better fit the claustrophobic setting. Danny Glover’s keyed-up performance, complete with violent outbursts and cheesy insults, keeps the film’s momentum amped up, especially when he takes on the Predator in a protracted final battle. Yet it’s supporting turns from Gary Busey and the late, great Bill Paxton — who delivers his patented schtick like a consummate pro — that build out Predator 2’s frenzied landscape chock-full of overworked, shortsighted professionals trying to put a lid on an alien invasion. By the end, it’s only Harrigan who comprehends the scale of who and what has been hunting them. —Vikram Murthi

85.

The Best Man Holiday (Malcolm D. Lee, 2013)

Malcolm D. Lee’s The Best Man Holiday doesn’t exactly pick up where his 1999 rom-com The Best Man left off. How could it? The Best Man arrived on a wave of other Black rom-coms — Love Jones, How Stella Got Her Groove Back, The Preacher’s Wife — that stood apart from the decade’s gangster films by highlighting a middle-class Black existence. Arriving nearly 15 years later, The Best Man Holiday reteams a once tight-knit friend group, a plethora of now successful Black entrepreneurs with families, for a Christmas celebration and reunion. Its drama rests on open wounds and broken words: Harper Stewart became a successful author with Unfinished Business, a book about his falling out with former friend and now record-breaking NFL running back Lance Sullivan after Harper had an affair with Lance’s bride and current wife, Mia. Harper, who hasn’t published a best seller since, comes to the Christmas party with his pregnant wife Robyn to not only mend fences with Lance but to offer to write his biography. The fun of The Best Man Holiday stems from its messiness: Chic dinner parties dissolve into ugly insults and knock-out, drag-out fights, giving way to thoughtful heart-to-hearts. Here, masculinity is vulnerable; the camaraderie of women is raw and open. Faith-based reflections guide each scene in a movie not afraid to be religious. Ultimately, the growth of the characters, their fresh conflicts and tribulations, sets the standard for how to revisit a lovable franchise without burying it in cash-grabbing mediocrity. —R.D.

84.

The Raid 2 (Gareth Evans, 2014)

The Raid: Redemption succeeds in its simplicity: a group of Jakarta police officers tasked with storming an apartment building run by a local crime lord. What follows is a barbaric, occasionally moving series of fight scenes, with rookie cop Rama (the incredibly adroit Iko Uwais) escaping by the skin of his teeth and enough exposed brains to make Martin Scorsese blush. The Raid 2 not only ratchets up that tension, but spreads it out over a dizzying two-and-a-half-hour family gang drama, with an undercover Rama at its grizzly center. The story is a bit harebrained — it includes rival gangs, multiple inter-family dramas, and too many betrayals to count. But a good sequel doesn’t necessarily live and die by its plot points, particularly when the audience has come to watch director Gareth Evans throw increasingly creative fight traps Uwais’s way. As the Indonesian crime world begins to crumble under Rama’s feet, we’re delivered the goods: a two-dozen-person melee in a bathroom stall, a prison riot in a mud pit, on-the-nose new villains Baseball Bat Man and Hammer Girl, and the glorious return of Yayan Ruhian (this time as a new character). In The Raid, Evans did the impossible, showcasing a kind of beatific brutality amid flying body organs and gushing blood. Watching him pull it off a second time feels like a magic trick. —A.S.

83.

The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (Fritz Lang, 1933)

When the Luxembourger author Norbert Jacques introduced the character Dr. Mabuse in his 1921 novel Dr. Mabuse the Gambler, the Nazi Party was in its infancy; a year later, Austrian filmmaker Fritz Lang would present his first cinematic version of the supervillain in a same-named silent film. Lang brought Dr. Mabuse to life as a man of seemingly supernatural powers, with his goal of spreading chaos and terror worldwide achieved through a network of sometimes-brainwashed, sometimes-possessed, sometimes-willing accomplices. By the time Lang released his April 1933 sequel, The Testament of Dr. Mabuse, was it really a surprise that the director and writer’s depiction of the character evoked then German chancellor Adolf Hitler, who had authorized the creation of the Dachau concentration camp a month before and would encourage the country’s first large-scale book-burning event a month later? Or that the Nazi Ministry of Propaganda banned the film? (It wasn’t shown in Germany until 1961, 16 years after Hitler’s suicide and Germany’s World War II defeat.)

Lang’s genre offerings — the sci-fi Metropolis and the noir thriller M — were linked to his political sensibilities, and The Testament of Dr. Mabuse is both a demonstration of Lang’s creative production techniques (the ghostly image of Mabuse that is able to duplicate itself and possess others) and of the ease with which “the tainted ideals of a world doomed to annihilation,” as Mabuse says, can spread among those who believe themselves disenfranchised and dispossessed. The evil genius spreading anarchy and dread has endured for decades since. Batman’s Joker, David Lynch’s BOB, and Stephen King’s The Outsider can all trace themselves back to the walls of masks frozen in expressions of agony in The Testament of Dr. Mabuse. —R. Hadadi

82.

28 Weeks Later (Juan Carlos Fresnadillo, 2007)

One would think it impossible to make a zombie thriller as unrelenting as director Danny Boyle and screenwriter Alex Garland’s original 28 Days Later, but director and co-writer Juan Carlos Fresnadillo’s sequel 28 Weeks Later meets the goal, delivering all the shocks and thrills one would expect from a second entry in a horror franchise while extending its humanistic interest in what becomes of once-healthy people after they are infected with a rage virus that turns them into rabid, violence-craving beasts. Weeks focuses on a couple of children who were vacationing away from their parents outside of Britain during the initial plague outbreak but are returned home, protected by a U.S. Army sniper, and reunited with their father Don, a coward who, unbeknownst to them, panicked and abandoned their mother while escaping a home besieged by the infected.

Like George Romero zombie films that acknowledge the pathetically recognizable afterimage of mortals who transformed into ghouls, Weeks cares very much about Don, an unlikable yet not entirely unsympathetic man who was already emotionally infected by guilt and self-loathing and whose disease just makes his condition official. After the father is transformed himself, his children remain sympathetic toward him even though they know he’d tear them apart if he got his hands on them. Confounding audience sympathies in the manner of all great horror films, Weeks doesn’t make you root for the bad guy to die because there are no bad guys in it, only people who, to greater or lesser degrees, struggle to live in a transformed world where death or sudden transformation lurk around every corner. —M.Z.S.

81.

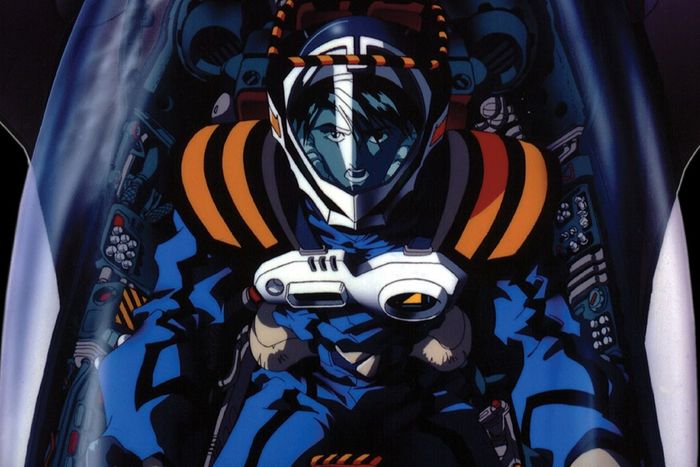

Macross Plus (Shōji Kawamori, Shinichirō Watanabe; 1995)

Macross Plus isn’t Robotech, but American audiences may recognize its jet-fighter designs as such. In fact, it’s the first official sequel to a Japanese anime from which the first arc of Robotech was adapted, Super Dimension Fortress Macross. By focusing on a new team of test fighter pilots, a new virtual idol, and studio Triangle Staff’s seamlessly blended CGI and traditional cel animation, Macross Plus took the ideas of that first Macross season and compressed them into a tight two hours of sound-barrier-shattering heroics. It’s a bit like Top Gun — if Top Gun’s fighter planes transformed into robots and Tom Cruise’s enemy was an AI named Sharon hellbent on hypnotizing humanity. (Nearly 30 years later, Sharon still looks uncanny thanks to Akira animator Kōji Morimoto.)

Despite wearing them, Macross Plus doesn’t lean on the throttle of its franchise trappings. You don’t really need to know much about stuff like “Protoculture” or the “Zentradi” to appreciate what’s going on. Macross Plus’s four-part original video animation (or: OVA) and reedited film were directed by Shōji Kawamori (creator and mechanical designer of Macross) and Shinichirō Watanabe (Cowboy Bebop), who keep the action moving at a rapid clip but also make time for patiently static moments focused on the characters’ states of mind. Screenwriter Keiko Nobumoto and composer Yoko Kanno — both of whom would later join Watanabe on Bebop — respectively bring their existentialist writing and eclectic musicianship to the script and soundtrack. Its kinetic dogfight sequences came courtesy of veteran animator Ichiro Itano, whose trademark “Itano circus” sequences make several appearances and propel the aerial combat throughout. The first Macross series (and Robotech) had great emotional heft, writing, dogfights, and music sequences, too, but Plus used its ’90s animation techniques, technology, limited time, and higher budget to take it all higher, faster. —E.V.B.

80.

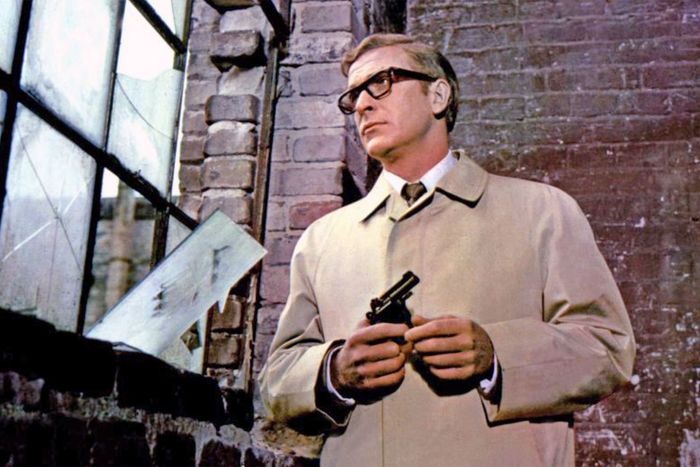

Funeral in Berlin (Guy Hamilton, 1966)

Imagine a spectrum of fictional spycraft with James Bond on one end and John le Carré on the other. The Harry Palmer series is halfway in between: the ’60s cool of Bond (Michael Caine sure can wear a pair of glasses) mixed with the darkness and moral ambiguity of le Carré. The first Palmer movie, 1965’s The Ipcress File, was a purely domestic affair. With Funeral in Berlin, under the direction of Guy Hamilton (who’d done Goldfinger for the other fellas), the franchise goes international. We’re in divided Berlin at the height of the Cold War, and Palmer’s assignment is to usher a defecting Russian colonel across the Berlin Wall. It all goes fubar, of course, with double crosses, sexy Mossad agents, and a reminder that our friendly West German allies happen to employ a lot of ex-Nazis. The Berlin locations mirror the film’s cynicism; underneath the FRG’s economic miracle, the wreckage of the war still lingers. The third installment of the series, 1967’s Billion Dollar Brain, would be a good deal sillier, and the Harry Palmer cinematic universe ended there — though Caine did reprise the role for a pair of ’90s TV movies. —Nate Jones

79.

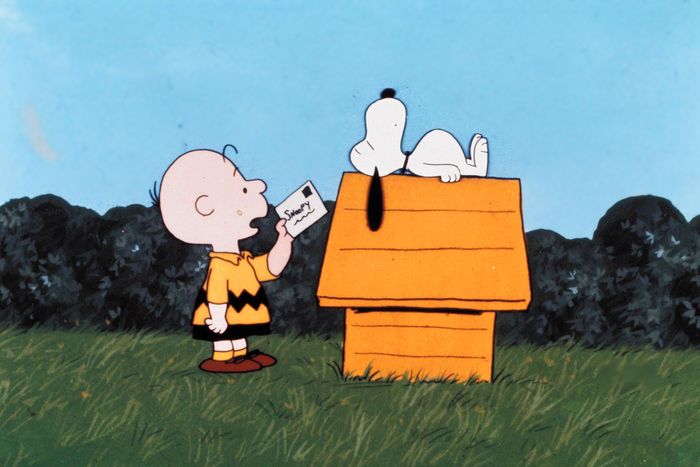

Snoopy Come Home (Bill Melendez, 1972)

The Peanuts gang sheds a lot of tears in this sweet story — the second major motion picture centered around Charlie Brown — about Snoopy’s reunion with his original owner, a girl named Lila who’s about to be released from a hospital stay, and the dog’s conflicted feeling about whether to live with her or return to his blockheaded owner. At an economical one hour and 20 minutes, Snoopy Come Home is one of those movies that imprints on the brain, especially when viewed at an impressionable age. That’s partly because it veers away somewhat from the template established by the late 1960s Peanuts television specials. While the style of animation remains the same — Melendez directed, Peanuts creator Charles M. Schulz wrote the script, and Lee Mendelson produced — the focus is much more on Snoopy and his buddy Woodstock, introduced for the first time onscreen here. The jazz of Vince Guaraldi is replaced by music written by the Sherman Brothers of Disney fame, yielding dreamy songs like “At the Beach,” the peppy, “Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious”-style “Fundamental Friend Dependability,” and the heartstring-puller “Lila’s Theme (Do You Remember Me?).” That soundtrack switch contributes to the more introspective vibe of the movie, which is refreshingly low-key compared to the overstimulated cadences and imagery of more contemporary animation. Though it certainly has its upbeat moments as well as a happy ending, Snoopy Come Home also stands out for doing something that fare aimed at young children usually does not: show people (and beagles) expressing genuine grief. —Jen Chaney

78.

Casino Royale (Martin Campbell, 2006)

Yes, Bond movies are sequels — even when some of the only things holding the thread together is the character’s name and his disposition for married women. So why did we select the 21st film in the franchise for our lone 007 entry? The same reason we ranked it the best Bond movie of all-time: it’s a brilliant reinvention of a man we thought we already knew, breaking already established tropes and giving viewers something else to latch onto other than just a witty Cold War-era killing machine. The point: to show how 007 became 007. When we first meet Daniel Craig’s Bond, he’s still a bit green: not yet double-O status and wide-eyed enough to fall in love — and not the “love” you see at the conclusion of every Bond film, with James winking at his latest infatuation as they ride off into the sunset. This love, between Craig and Eva Green’s Vesper Lynd, felt intimate and carnal. Meanwhile, director Martin Campbell’s fight sequences were fresh and exciting in ways previous Bond movies never seemed to pull off. (All due respect to Pierce Brosnan, but it’s laughable trying to imagine him parkouring his way through a Madagascar construction site as swiftly as Craig does.) Past 007 chapters had showcased destruction, pain, sex, tension, and ego (also: poker!) many times before. None had done it in a way that felt as fallible, or as human, as Casino Royale did. —A.S.

77.

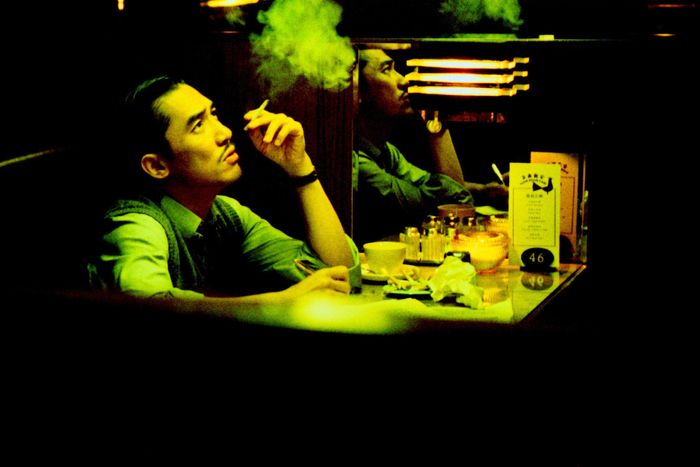

Election 2/Triad Election (Johnnie To, 2006)

Johnnie To’s Election films are scathing indictments of the self-mythologizing of the Hong Kong triads and the greed and violence lurking under traditions and formal ceremonies that get thrown out as soon as anyone involved feels like acting out. 2005’s Election is centered on a showdown between two would-be chairmen — the seemingly restrained Lok (Simon Yam) and the ostentatious Big D (Tony Leung Ka-fai) — though the ending is a reminder that neither was actually the kind of principled criminal the organization pretended to be made up of. The second film is even brisker than the first in its backroom machinations and bloody betrayals, with Lok planning on greedily breaking the rules in order to hold onto power and his young protégé Jimmy getting pressured to run against his mentor by the mainland police. The film plays out like a dark fable in which maintaining a certain level of corruption is ideal for everyone involved, including the mainland cops who may as well be the most powerful cartel of them all, and the biggest fools are those who think they can extricate themselves from the illicit underworld they’ve long been a part of. —A.W.

76.

Wes Craven’s New Nightmare (Wes Craven, 1994)

When I was nine years old, no movie terrorized my waking hours like Wes Craven’s New Nightmare. My child brain was simply unable to handle the meta-textual twist of the seventh Nightmare on Elm Street movie, in which Freddy Krueger terrorizes the people who made the original films — including stars Heather Langenkamp and Robert Englund and Craven himself. The plot seems designed to short-circuit the usual parental reassurances: Don’t be scared. It’s just a movie! That’s what everyone said in this, too, and look how they all got murdered! For a year, I saw the specter of Freddy lurking everywhere — in dark closets and the forests next to the highway. I was never able to listen to “Losing My Religion,” which soundtracks the movie’s opening kill, ever again. Needless to say, I did not rewatch it to write this blurb, so you’ll just have to trust my third-grade self, who says this is the scariest sequel ever made. —N.J.

75.

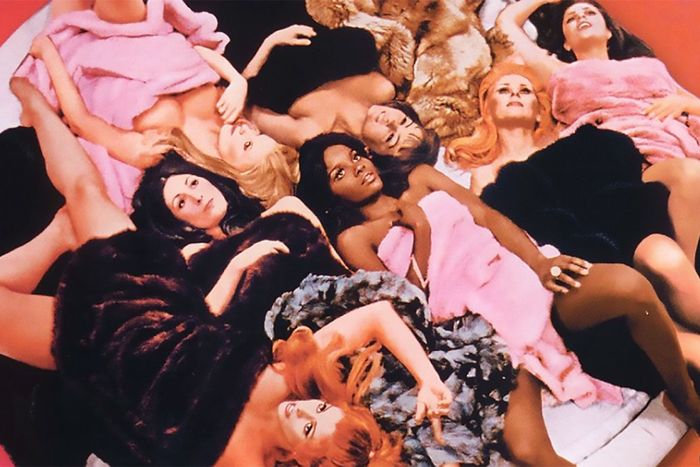

The Decline of Western Civilization Part II: The Metal Years (Penelope Spheeris, 1998)

The first and third films in Penelope Spheeris’s documentary trilogy focused on Los Angeles’s hardcore scene, going from capturing performances of Black Flag and Germs at clubs to exploring the lives of gutter punks carving out a precarious community for themselves on the street. But it’s the second installment that remains an all-time banger, venturing into the excesses and bombastic self-mythologizing of glam rock and heavy metal musicians. Spheeris let her subjects choose where they wanted to be interviewed, leading to some inspired settings — Kiss’s Paul Stanley in bed with three lingerie-clad women, W.A.S.P.’s Chris Holmes wasted in a pool with his mother looking on. So what if the shot of Ozzy Osbourne spilling OJ everywhere while making breakfast and talking about drug use was faked? It felt spiritually true. Spheeris’s film has been credited with killing off the scene it documented, though if that’s accurate, it was really by way of self-inflicted wounds. But The Metal Years is most potent seen in contrast to the films surrounding it, an ode to artifice and indulgence set between two documents of artists and fans in pursuit of a nihilistic, dead-end authenticity. —A.W.

74.

The Fast and the Furious: Tokyo Drift (Justin Lin, 2006)

Are there better movies in the Fast & Furious series? Debatable. Are there bigger movies? Without question. But Justin Lin’s 2008 installment was the crucial point for the now-megafranchise, proving that it was bigger than either of its original stars, who at that point had moved on, with Vin Diesel deigning to show up for a late cameo appearance in exchange for the rights to the Riddick series. By transplanting the action to Japan and away from quarter-mile racing into balletic feats of drifting, Lin opened the door for more globetrotting and escalatingly absurd automotive stunts as well as unlikely bursts of poetry — the quiet moment as racing cars glide through the crowds at Shibuya Crossing, shocked faces reflected on the windshield, is still one of the best things the series has done. Screenwriter Chris Morgan began engineering a wild but stubbornly consistent chronology for the series from this point, establishing its tone of taking stupid things very seriously. And in having Sung Kang as a scene-stealing supporting character, Tokyo Drift stealthily connected back to Lin’s milestone of Asian American cinema, Better Luck Tomorrow, while setting the series on a course toward its multiracial, multinational present. Eventually all the stars would return, but it’s Kang who represents the series’ heart, brought back from the grave first by timeline contortions and, eventually, screenwriterly magic. —A.W.

73.

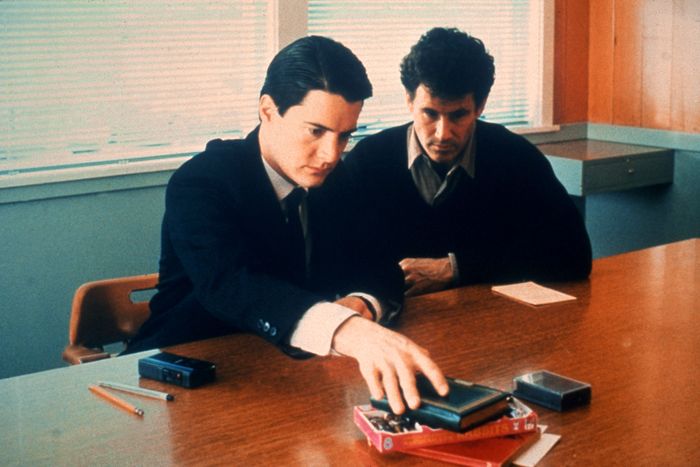

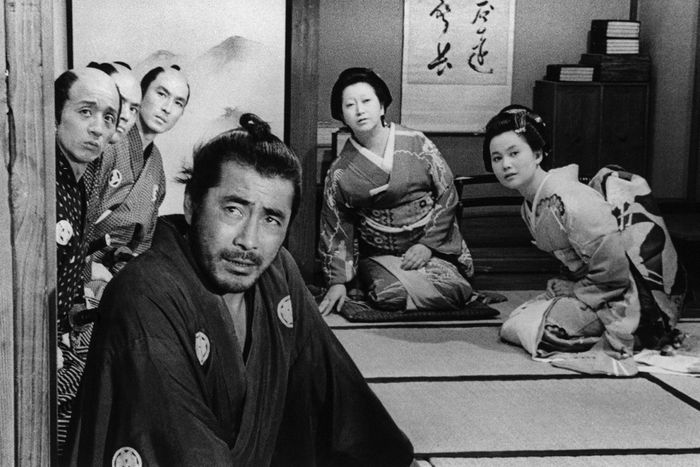

Samurai III: Duel at Ganryu Island (Hiroshi Inagaki, 1956)

“Take up your stance with the sun behind you,” master swordsman Miyamoto Musashi taught in his sword-fighting manual The Book of the Five Rings. Musashi might have appreciated that director Hiroshi Inagaki took the tip to heart when he and cinematographer Kazuo Yamada filmed the titular fight in the climactic entry of the Samurai trilogy, Duel at Ganryu Island. Drenched in the light of a creeping sunrise, the duel is a dramatic, wordless exchange of footwork, swordsmanship, and bravado. Yamada and Inagaki’s frames, shot in Eastmancolor, erupt from the screen as silhouettes of Musashi and his opponent Sasaki Kojirō clash. And as technically proficient as the filmmaking and swordplay are, they only work half as well as they do because they close out the stories of these two men established in the films that came before, which dramatized Musashi’s self-actualization beyond a life of pure violence and, later, Kojirō’s descent into it as he chased renown.

The real Musashi was never quite as heroic as Inagaki made him out to be in his films. (And Inagaki made a lot of them; the color Samurai trilogy, a remake of his own earlier black-and-white Musashi trilogy, and four films about Sasaki Kojirō.) Nor is he always that heroic; he’s quick to dispose of or conveniently reattach himself to the women in his life without much care for their feelings. Nonetheless, the films made a myth thanks to their indelible, crowd-pleasing bona fides, and it led to more roles for Mifune, like the very different ronin he played in Yojimbo and its own noteworthy sequel, Sanjurō. —E.V.B.

72.

Paddington 2 (Paul King, 2017)

One of the internet’s favorite sequels and the finest film Hugh Grant ever made, according to Hugh Grant, Paddington 2 is even more of a delight from beginning to end than the previous Paddington, which was also quite delightful. Built around an easy central narrative — Paddington wants to send his Aunt Lucy a pop-up book as a birthday gift, but multiple obstacles get in his way — the film delivers charming set piece after charming set piece and looks absolutely stunning while doing it. Its saturated colors and golden glow rival the jewel-tone twinkle of Moulin Rouge, while its unexpectedly joyful (and very pink) prison scenes would not seem out of place in a Wes Anderson film. Every family movie should aim to be this gorgeous. All the actors in the excellent cast seem to be thoroughly enjoying themselves, and yes, that includes Grant, as a scheming, villainous magician capable of assuming multiple personas. This movie is a beam of light, an instant serotonin boost, and a cure for pessimism, if only temporarily. When that little bear with Ben Whishaw’s voice insists that “if you’re kind and polite, the world will be right,” you absolutely believe him. —J.C.

71.

War for the Planet of the Apes (Matt Reeves, 2017)

Between The Batman, his remake of Let the Right One In, and his work on the Planet of the Apes reboot franchise, director Matt Reeves has spent years thinking about preexisting canon. When War for the Planet of the Apes came out in 2017, he pointed out that while the franchise’s “what” has always been right there in the name, its “how” opened up lots of narrative possibilities: “When you know the end of the story, the focus changes.” So Reeves focused, in War for the Planet of the Apes, on making his lead Caesar “a mythic ape figure, like Moses.” The reboot franchise accomplishes this through heavy serialization and politicization. Across three films, we get to know Andy Serkis’s Caesar as a main character, watching him strive, fail, face his former ally in combat, raise a son of his own, and face a final boss in a human paramilitary leader. Woody Harrelson’s murderous Colonel will stop at nothing in his fight for human dominance. In the Colonel, Caesar faces an endangered shadow of himself, the perfect opposite for a folk hero at the end of his story. —E.V.B.

70.

Jackass Number Two (Jeff Tremaine, 2006)

Jeff Tremaine’s big-screen continuation of his hit MTV series with star Johnny Knoxville and his band of merry, self-obliterating pranksters was the first movie in the series to look at itself not merely as an unscripted comedy but as a statement on friendship, mortality, maturity, and aging. It was also the first to openly reflect on the audience’s emotional bond with a bunch of dudes whose greatest purpose in life was to risk death and injury to show their love for each other. Knoxville and the gang make like a family of Wile E. Coyotes. Knoxville rides a rocket; Chris Pontius lets his penis be made up to resemble a mouse and then waits to see if a snake will bite it; Ryan Dunn is slammed into a garage door while sitting in a runaway shopping cart; and Ehren McGhehey wears a beard created from pubic hair donated by the performers and crew — one of whom unfortunately has crabs. Each new set piece brings a new can-you-top-this spectacle. But the foundation of the film is the homosocial love between the men, which is always nearly indistinguishable from same-sex affection and desire — a fact that is both acknowledged and celebrated in the film’s climactic staging of “The Best of Times” from the Broadway musical-adaptation of the gay-themed domestic farce La Cage aux Folles. —M.Z.S.

69.

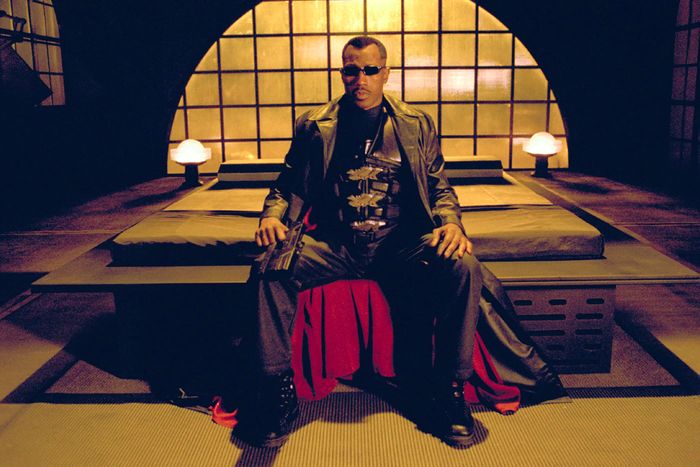

Shaft’s Big Score! (Gordon Parks, 1972)

Gordon Parks’s Shaft helped launch the blaxploitation genre and remains a classic to this day. But its sequels tend to be under-celebrated — perhaps because they didn’t have the rough, gritty edges of the first movie. Shaft’s Big Score, however, is a fantastic picture in its own right. With this follow-up, Parks took full advantage of the bigger budget to stage his share of elaborate action sequences — including a climactic, explosive car-helicopter-boat chase/shoot-out on the East River and in the Brooklyn Navy Yard. He and writer Ernest Tidyman played around a bit more with the figure of John Shaft, giving him Bondian flair and a slightly more distant demeanor. Parks tended to value his other, more serious films over his genre efforts, but we can see his earnest classicism peeking through in Shaft’s Big Score, which has an elegance and warmth that runs counter to its reputation as a lesser sequel. Helping set the mood is the gracefully jazzy score — not coincidentally composed by Parks himself (one of America’s great Renaissance men), as Isaac Hayes, who had won an Oscar for the first film’s music, reportedly asked for more money than MGM was willing to part with. —B.E.

68.

A Better Tomorrow II (John Woo, 1987)

John Woo’s sequel to the massively successful A Better Tomorrow certainly adopts the “more is better” philosophy: more guns, more blood, and more bodies. The film’s two big shoot-outs, one in a hotel and the other in a mansion, are some of the best of Woo’s career — a high-wire ballet of bullets and bombs designed to elicit loud cheers from audiences. Despite his character, Mark, being killed in the first film, Chow Yun-fat returns as Mark’s twin brother and spends the entire time kicking ass, taking names, and trying to restore the sanity of a former Triad member. The plot is basically irrelevant — no longer on opposite sides of the law, brothers Ho and Kit team up to investigate the activities of Ho’s mentor — existing only to move the film between cool, eye-raising set pieces. Woo allegedly disowned A Better Tomorrow II, save for the final shoot-out, after a protracted dispute with producer Tsui Hark over the film’s editing. While Woo would go on to make even more acclaimed Hong Kong features (like The Killer and Hard Boiled) before a period in Hollywood and Hark would create his popular Once Upon a Time in China series, A Better Tomorrow II represents a key synthesis of styles and ideas between the two filmmakers. And even if it didn’t, it would still feature that epic scene of Chow browbeating an Italian mobster after the latter insults his fried rice. —V.M.

67.

O Lucky Man! (Lindsay Anderson, 1973)

In terms of scope and ambition, O Lucky Man! is Godfather II to Lindsay Anderson’s 1968 If …. It is a thematic adaptation of Voltaire’s Candide functioning as a sprawling epic of disillusionment with the British class system and, more to the point, the irresolvable corruption of colonialism, imperialism, and capitalism. Our hero, Mick Travis, whom we remember as a rebellious schoolboy opening fire on the mad upperclassmen and headmasters of his boarding school, moves from the most promising clipboard-holder in his coffee warehouse up every rung of the corporate ladder. Along the way, he encounters a corrupt police force interested only in the preservation of wealth for the robber barons, a broken political system in which “the dividing line between the House of Lords and Pentonville Jail is very, very thin,” and a prison-industrial complex used as a cudgel to oppress the lower classes. Rather than coming off as a dreary sociopolitical screed, however, Anderson’s sequel tells it all through surreal, dreamlike vignettes bookended by Alan Price’s arch tunes, which function as a Greek chorus to Mick’s gradual loss of innocence. Anderson simmers all the motives of man into a thick reduction of lust and greed to create a singular film — not only for the breadth of its targets but for the freshness of its incandescent rage. —Walter Chaw

66.

Dracula Has Risen from the Grave (Freddie Francis, 1968)

A black-and-white poster for Dracula Has Risen from the Grave features a buxom woman with pink Band-Aids on her neck and “(obviously)” added below the title. The fourth entry in Hammer’s Dracula series isn’t quite as hip as its poster, but it does feature Christopher Lee’s iteration of Dracula dripping blood from his eyes. It’s splashes of style like that from director Freddie Francis that make this entry in the franchise so alluring. Lee’s first outing as Dracula introduced the image of fangs, a red satin-lined cape, and beady red eyes. This Dracula exudes a sexual heat Bela Lugosi’s lacked (although Lee is not quite as horny as Frank Langella would be a few years later) and proves that a vampire film does not need familiar characters like Van Helsing to flesh out its world. All you need for a good time is an isolated town, some voluptuous women, and good old-fashioned bloodlust. Bright scarlet blood is everywhere — from dripping from the corpse of a woman tumbling out of a church bell in the opening scene to Dracula’s resurrection to the gory finale. Although Lee would go on to play the Prince of Darkness four more times, Dracula Has Risen From the Grave is the last film to which Lee brings all of his powers as a star — and the last worthy of his talent. —Marya E. Gates

65.

John Wick: Chapter 3 – Parabellum (Chad Stahelski, 2019)

There is a magical alchemy to the John Wick franchise that director Chad Stahelski, writer Derek Kolstad, fight choreographer Jonathan Eusebio, and star Keanu Reeves have created together, and it has made each sequel to the original 2014 film more deliriously bonkers than the last. John Wick: Chapter 2 has some exceptional scenes (including the rave catacombs and “excommunicado” sequence) and broadened the series’ mythology with its explanations of the High Table and blood-oath markers. But it pales in comparison to John Wick: Chapter 3 – Parabellum — a 130-minute cascade of “What? What!” and “Hold up! How?” for the film’s even longer takes, more complicated sequences, and wilder bravura moments from Reeves’s very-much-back assassin.

Consider this brief list of frankly wondrous set pieces: Wick killing someone with a book, wielding a samurai sword on horseback around New York City, teaming up with Halle Berry’s ex-assassin Sofia Al-Azwar and her dogs to fight their way out of a Moroccan casbah, and brawling against Mark Dacascos’s Zero and his students in the Continental’s all-glass room with shards shattering and falling all around them. Parabellum shades in Wick’s backstory through his ties to the Ruska Roma syndicate led by Anjelica Huston’s Director, furthers his alliance to Ian McShane’s Winston and Lance Reddick’s Charon before blowing up that teamwork in advance of John Wick: Chapter 4, and never loses sight of the most important element of this franchise: how adorable Daisy is. Keep her safe at all costs. —R. Hadadi

64.

Tales from the Crypt: Demon Knight (Ernest R. Dickerson, 1995)

How the hell did this stand-alone film make the list? Well, it spun off of (and, in our terms, “sequelized”) the perfectly sordid and far too underrated HBO series Tales From the Crypt — its excessive host, the Crypt Keeper, voiced by John Kassir. And the film deserves to be here. It opens with a righteous car chase on a desolate New Mexico road between a powerful demon known as the Collector and a drifter named Frank, who has been tasked with protecting an artifact since World War I that contains the blood of Christ and allows its keeper to be immortal. Frank finds his way to a grand, isolated hotel that used to be a church populated by character actors Thomas Haden Church, Dick Miller, and C. C. H. Pounder as the dame managing the joint. When the Collector tap dances his way into the hearts and minds of these mortals to get the key and move on up the ladder, so to speak, things quickly turn hellish. Demon Knight is powered by practical effects rendering bodies bloodied, broken, mutated, and, in some cases, demonic. Full of puns and vicious jokes, bristling with violence and playfulness, it’s grungy and fueled by pulp sensibilities. The movie is brought to life by the great Ernest Dickerson; it can be argued that, with his direction and Jada Pinkett Smith as the final girl who takes on Frank’s cause, this too is a sly entry in the canon of Black cinema. Like many of the 1990s entries in this list, Demon Knight is fueled by the prowess of later-billed actors, but it’s Billy Zane who really takes it to operatic heights. He’s gloriously arch, hot as hell. His line readings are delectable and dangerous — like chocolate cake dolloped with poison. —A.J.B.

63.

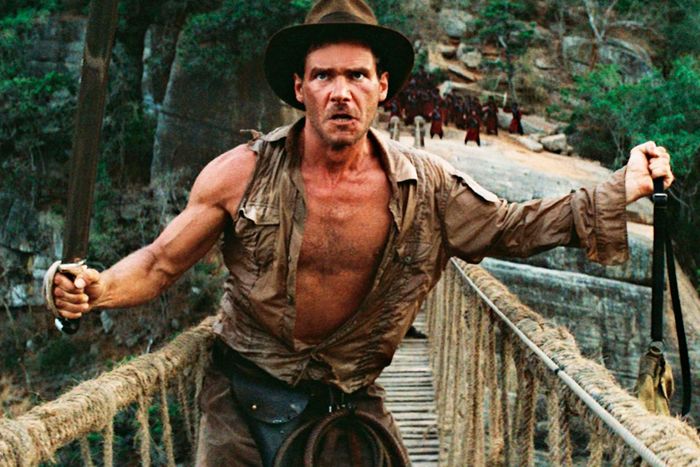

Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (Steven Spielberg, 1984)

Simultaneously dazzling, clever, offensive, disgusting, and bizarre, Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom — the follow-up to Raiders of the Lost Ark — showed a cruder, meaner, more selfish and openly misogynistic Jones getting embroiled in shenanigans in colonial India, where a modern variant of the ancient Thuggee cult that has stolen sacred Sankara stones from a nearby village operates in catacombs beneath an outwardly respectable seat of government. There are savage beatings and torture scenes; a ceremony in which a man’s heart is ripped from his chest and his body roasted in a lava pit; a banquet featuring live eels, hand-size scarab beetles, and monkey brains; a spike chamber teeming with glistening insects; images of enslaved children being beaten, starved, and whipped in a diamond mine; and a long sequence in which Indy is forced to drink a potion that turns him evil and moves him to abuse his child sidekick Short Round (Ke Huy Kwan) and lower his love interest, gold digger Willie (Spielberg’s future second wife Kate Capshaw), into a magma pool.

This movie was one of two summer 1984 Spielberg hits (the other was Joe Dante’s Gremlins, which Spielberg executive-produced) that so appalled the Motion Picture Association that it moved to create a new rating, PG-13, to label films that weren’t exactly adult but were unsuitable for younger children. It’s a problematic classic par excellence: casually racist and historically and culturally insensitive, even for an Indiana Jones film, but one of Spielberg’s greatest sustained displays of pure-action filmmaking — viscerally thrilling and, at times, punishing even by today’s more heightened standards. It mixes Buster Keaton–style slapstick, James Bond–style ludicrous stunts (such as a fall from a plane on an inflatable raft), and ghastly imagery one would rarely expect to encounter outside of an R-rated horror film. It marks one of the few times that Spielberg seemed to be fully surrendering to his id without keeping one eye on the audience to make sure it feels safe and protected. —M.Z.S.

62.

The Lost World: Jurassic Park (Steven Spielberg, 1997)

The wonder of Jurassic Park was in watching dinosaurs again walk the earth in a terrifyingly realistic way. While The Lost World sees Spielberg, egoless yet again, using some of the visual markers audiences loved from the first movie — the thrum of a T. rex’s footsteps, the darting eyes of a velociraptor — attempting to summon that same feeling of awe for a sequel was always going to be impossible. That leaves The Lost World as less of a study on the beauty of an extinct species and instead a big dumb-fun action film filled with extravagant set pieces and humans behaving badly. It all manages to stay on course thanks to the charm of Jeff Goldblum’s returning quasi-everyman Dr. Ian Malcolm, and his infinite contempt for madcap billionaire John Hammond (Richard Attenborough, in a measly two scenes). There’s a sick fun in watching Dr. Malcolm being repeatedly proved right, even when it costs his friends and the group of hunters they’re fighting against their limbs. No, there’s not a lot of subtext to that. But who needs that when you get to see a big ol’ T. rex stomping its way through the streets of San Diego? —A.S.

61.

Final Destination 2 (David R. Ellis, 2003)

One of the many, many beauties of the Final Destination franchise is that because the series’ villain is death itself (as in, like, the concept), you really don’t need to bother with any strained explanations as to why it has returned for a new movie. Death is never vanquished, just (momentarily) thwarted, which simply means that it keeps coming back to finish the job. That’s a deliciously cinematic premise — watching victims get offed through an assortment of increasingly unlikely accidents and coincidences that combine to turn ordinary life into a series of Rube Goldberg–inspired death traps. The cinematic creativity involved in the kills means that sequels are always welcome, because we’re constantly waiting to see how the filmmakers will top the previous deaths. That said, Final Destination 2 opens with what is still the most spectacular sequence of them all: a delirious, nightmarish highway pileup that serves as an unforgettable showcase for director David Ellis’s special way with mayhem. (He was, after all, a stunt coordinator and second-unit director.) Still the high point of the series, this entry also distinguishes itself through the fact that, unlike in most horror movies (and especially horror sequels), its characters are likable and actually seem willing to cooperate against the invincible force that’s picking them off one by one. They’re not all just jerky teens, in other words. This, in turn, adds an extra element of pathos to their inevitably gruesome ends. —B.E.

60.

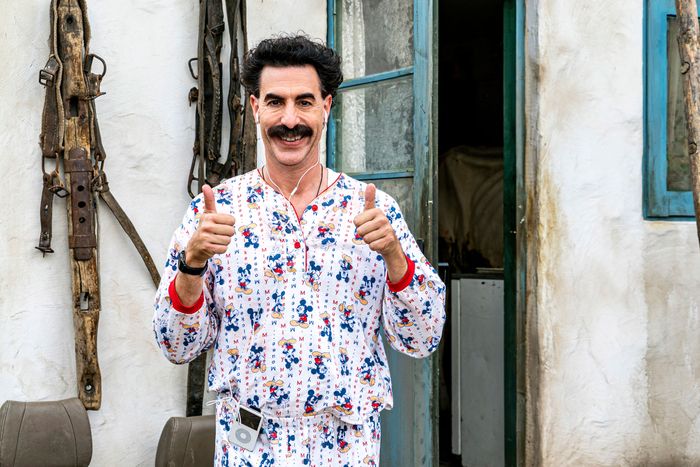

Dhoom 2 (Sanjay Gadhvi, 2006)

Running on diesel and Bollywood dance numbers, Dhoom 2’s ensemble cast of cops and robbers make street racing look so badass that it was blamed for a rise in bike-stunt accidents among Indian youth. A team of police officers led by steely-eyed ACP Jai Dixit pursues the international and elusive thief Mr. A and his pseudo-partner Sunehri. Despite an erotic game of rainy basketball and an opener in which A rips off a mold of the queen’s face before skydiving onto a train, Dhoom 2 has an uncomplicated core idea; it’s a sequel that extols the virtues of sequels. Cop and thief meet in a movie theater — with Sunehri in the middle as the screen blares a Cars fight scene between Lightning McQueen and Mater. Lovelorn cop Ali envisions running along a beach with every woman he meets, including twins Shonali and Monali Bose, in Baywatch-esque red swimsuits. The movie is kitschy and obsessed with duplicity at every turn. Just like A’s shifting identities — Snow White’s dwarf, a Greek statue, Queen Elizabeth — Dhoom 2 shows how great reinvention can be when it’s not taken too seriously. —Ashley Shannon Wu

59.

Superman II (Richard Lester, 1980)

The second Superman established plenty of the superhero-sequel conventions that other titles would mimic moving forward: Superman is joined by familiar faces and fights brand-new villains (see also Batman Returns and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles II: The Secret of the Ooze). He loses his powers (Spider-Man 2, X-Men: The Last Stand). He gets the girl only to lose her (Batman Returns, Spider-Man 2, The Amazing Spider-Man 2, The Wolverine). Everything escalates. If Superman convinced the world a man could fly, Superman II’s job was to convince us that he could fly higher while also retaining an essential humanity.

Four decades later, all the Zod stuff still rules, because Terence Stamp plays an evil megalomaniac so well that he can steal scenes from Gene Hackman. The superhero action, by the standards of the early ’80s, is superb and suffused with a screwball humor that’s practically extinct in modern blockbusters — especially Superman films. The Richards, Donner and Lester, deserve credit for how much of Superman II feels exciting and fresh (even if Donner famously didn’t want to share credit after being replaced as director). What doesn’t work, however, is the love story between Lois and Clark — a shame given how easy Margot Kidder and Christopher Reeve’s chemistry felt onscreen. Superman lies to Lois a lot in this film — even when she has him dead to rights. At their romance’s emotional climax, when she admits that she doesn’t want to share him with the world, he robs this successful, hard-as-nails reporter of her agency with a kiss that wipes her memories. It feels weak-willed — more so now given how the latest Spider-Man film ends. Like the lessons of so many other sequels, not all of Superman II’s were worth rehashing. —E.V.B.

58.

The Revenge of Frankenstein (Terence Fisher, 1958)

For decades, director Terence Fisher shelled out a string of sturdy horror sequels based on characters like the Mummy and Dracula for Hammer Film Productions — a London-based studio dedicated to genre. Among them was The Revenge of Frankenstein, the adventurous 1958 sequel to The Curse of Frankenstein, wherein Baron Victor Frankenstein (character actor Peter Cushing), three years after his monster’s disaster, escapes the guillotine to reestablish himself in Carlsbrück as a confidant to the wealthy and physician to the poor. A snooping Doctor Hans Kleve, having sussed out Baron Frankenstein’s real identity, arrives in search of knowledge: How does he harness the power of God? Baron Frankenstein has learned from his past mistakes. Instead of using a defective brain, he plans to transplant the hunchback Karl’s brain into a poor man’s body. The masses know Cushing as Grand Moff Wilhuff Tarkin, but the initiated will recognize him as the shouldering star of Hammer Films — all lanky body and chiseled, ghostly visage. The gorgeous technicolor of Revenge deepens Cushing’s sockets to grim ends (ruby reds and jade greens painting the screen), blending Victorian opulence with wonderful B-movie style. The film reminds me of the craftsmanship behind the props and practical effects of the 1950s; dismembered eyeballs staring at a flame are still and simply unnerving. Then there’s Quitak giving one of horror cinema’s most unhinged, physically attuned performances in playing the monster not as a grunting specter but as a real man. —R.D.

57.

Ginger Snaps 2: Unleashed (Brett Sullivan, 2004)

John Fawcett’s 2000 supernatural dramedy Ginger Snaps is a cult classic for a reason — a funny, sexy, and utterly savage film about adolescence by way of lycanthropy. The original starred Emily Perkins and Katharine Isabelle as sisters Brigitte and Ginger Fitzgerald, high-school outcasts whose close relationship starts splintering when Ginger gets bitten by a werewolf. It gets darker as it goes along, so it only makes sense that its expectation-defying follow-up starts bleak and gets bleaker as it follows Brigitte, solo after killing her sister, as she tries to stave off her inevitable transformation with injections of monkshood. What’s so satisfying about Ginger Snaps 2 is how hard it’s willing to go, refusing to allow its sardonic teen roots to temper a desperate scenario while still finding time for jokes about teen hormones and literally hairy palms. To land Brigitte in rehab, where in trying to protect her the facility prevents her from taking the shots she’s using to keep from transforming into a monster, is inspired. To have a young Tatiana Maslany playing a fellow patient who offers a tentative replacement for the friendship Brigitte used to have with her sister is even better, leading to an ending that’s more brutal than the one in the first film. —A.W.

56.

Supercop (Stanley Tong, 1992)

Everything is better with Michelle Yeoh. The Police Story franchise was already an exhibition for international film star Jackie Chan, who directed, co-wrote, and choreographed the action scenes and stunts for 1985’s Police Story and 1988’s Police Story 2 with his team of collaborators. The fast-paced films focused on Chan as Inspector Chan Ka-Kui and emphasized Chan’s singular mix of silly slapstick humor and bone-crunching martial arts — or seemingly singular until Yeoh was paired with Chan as a co-lead in Police Story 3, or Supercop. As Inspector Yang Chien-Hua, the straight woman to Ka-Kui, Yeoh is an absolute treat to watch, adept at both the physical demands of the role and the comedic timing needed to play off Chan’s zaniness. Those skills come together particularly well during a scene in which Ka-Kui is undercover as a criminal and Chien-Hua poses as his sister. It’s an elaborate setup and Yeoh’s performance helps sell the ruse. She’s exuberantly physical, delivering a leaping split kick in pigtails and a fuzzy cardigan, but also believably exasperated with Ka-Kui, snarking at his failed chopstick attack with “Can’t you throw?” The film’s stunt work gets increasingly insane — rocket launchers going off during a drug-exchange shoot-out in the Golden Triangle; Chan hanging off a helicopter to save his abducted girlfriend (Maggie Cheung) — but it’s Yeoh you’ll keep searching for as she zooms along in a motorcycle and hangs onto the top of a speeding van. —R. Hadadi

55.

Kill Bill: Volume 2 (Quentin Tarantino, 2004)

In his review of Kill BIll: Volume 1, Roger Ebert called the film “all storytelling and no story.” Volume 2, released about six months later, delivered on the latter, replacing the hyperstylized, ultraviolent bloodshed of the first film with the dialogue-happy delirium for which Quentin Tarantino is known. The script is delightful. Bill massacred the Bride’s entire wedding party and tried to kill her and her unborn child. Bill’s recollection when the Bride confronts him? “I overreacted.” Volume 2 is full of character work like that, big and small. In another scene, Budd reveals to Bill, his brother, how guilty he feels about the whole bloody affair. Bill asks if he’s kept up with his swordplay, and Budd replies that he had pawned his priceless Hattori Hanzo sword for $250, to Bill’s horror. As we learn later, though, the sword was in Budd’s trailer, stuffed in a bag with his golf clubs, and an inscription on it read, “To my brother Budd, the only man I ever loved — Bill.” Kill Bill was originally produced as one film and split in half for release, and it’s to Tarantino and Thurman’s credit that its two halves feel complementary rather than out of sync, which was Tarantino’s complaint with a couple of movies also produced consecutively and released six months apart in 2003: The Matrix sequels. —E.V.B.

54.

Top Gun: Maverick

Who in the world actually wanted a Top Gun sequel? Even Tom Cruise didn’t; he resisted the idea for decades and was reportedly still reluctant even as producer Jerry Bruckheimer was commissioning scripts for a proposed follow-up in the early 2010s. But by the time director Joseph Kosinski’s COVID-delayed Top Gun: Maverick finally hit theaters, the world not only wanted a Top Gun sequel — it needed it. The film’s resounding success with both critics and moviegoers certainly speaks to many of its much-discussed achievements: the authenticity of its flying scenes and effects; the return of a crowd-pleasing theatrical entertainment that actually bothers to properly utilize the big screen; a rousing adventure that doesn’t skimp on drama or emotion; and the return of Tom Cruise, megawatt movie star. But perhaps even more important, at a time when so many of our biggest blockbusters are bringing back old casts and old plotlines to capitalize on the nostalgia factor, Maverick somehow manages to do all that while acknowledging that the world has changed. As you watch it, you’re reminded of how much time has passed since the original Top Gun and of how much everything has been transformed in the years since. The film is a nostalgic wallow that also serves as a rebuke to nostalgic wallows. And it takes a very special kind of movie, made with genuine cinematic dexterity and sophistication, to navigate that particular obstacle course. —B.E.

53.

Pusher II (Nicolas Winding Refn, 2004)

Nicolas Winding Refn’s directorial debut, Pusher, was supposed to launch his career, not a franchise. But after his first English-language film, the 2003 John Turturro thriller Fear X, bankrupted his production company, Refn found himself with few options but to turn back to the low-budget crime drama that served as his international breakout. The irony is that the sequels he made were richer and more rewarding than that first film, which was very much committed to a young man’s idea of sordid authenticity. While Pusher focused on the travails of low-level Copenhagen drug dealer Frank, Pusher II turns its attention to his hapless sidekick, Tonny, who happened to be played by an up-and-coming actor named Mads Mikkelsen. This good taste in casting aside, the film becomes an anguished meditation on fathers, sons, and masculinity with Tonny revealed to be the child of a local kingpin who sees him as a disappointment. Pusher II builds on the brutal dynamic from the first film to create a portrait of a character desperate to please people who have no respect for him and forever prone to trusting those who’d betray him instantly to protect themselves. Its boldest choice is not to revel in the grittiness of the first film but to follow someone unable to rid himself of the softness that makes him so ill suited to the life he’s chosen. —A.W.

52.

After the Thin Man (W.S. Van Dyke, 1936)

No one ever came to The Thin Man series — MGM’s dependable box-office draw, never cheaply made — expecting a difficult-to-solve whodunit. Audiences watched because of the natural charm of married sleuthers Nick and Nora Charles and their adorable terrier. Totaling six films, the series began in 1934 with The Thin Man. The second installment, After the Thin Man, was released in 1936 and directed by the efficient W. S. Van Dyke, who helmed the franchise’s first four entries. It locked in a bankable formula: On the verge of retirement, a surprise case pulls the sardonic Nick and adventurous Nora through a series of red herrings and predictable turns. In this instance, the pair, returning home for New Year’s Eve, are called by Nora’s family matriarch, the cold and calculating Aunt Katherine, to investigate the disappearance of the philandering husband of Nora’s panicked cousin. A young Jimmy Stewart plays an unrequited crush. It’s an early turn by him, his aw-shucks prewar persona on display. But it’s Powell and Loy, delivering saucy one-liners at a whiz-bang pace (a calling card in their astounding 13 other collaborations), who make a film that otherwise luxuriates in fashion and boozy comedy churn. —R.D.

51.

The Look of Silence (Joshua Oppenheimer, 2014)

Joshua Oppenheimer’s companion piece to his acclaimed feature The Act of Killing, crucially shifts perspectives from oppressor to victim. In The Act of Killing, Oppenheimer gave a former executioner in the Indonesian genocide the opportunity to restage his crimes like a movie with the help of filmic elements such as costumes, makeup, and special effects, until the Hollywood artifice gives way to memories of real terror. In The Look of Silence, however, an optometrist named Adi uses eye exams as an excuse to confront and interrogate perpetrators of the genocide about their involvement. What these men don’t know is that Adi’s brother was one of the many innocent people slaughtered. All Adi wants is an acknowledgement of the horrors. Oppenheimer provides audiences a queasy firsthand look at denial and self-justification. “The past is past,” many of these men repeat. Interspersed between the interviewers are scenes of Adi caring for his elderly parents, who are living reminders of the victims left alive from the atrocity. Though lacking The Act of Killing’s meta element, The Look of Silence is no less powerful than its predecessor. Its relative straightforwardness gives way to a skin-crawling uneasiness of a noxiously evergreen subject: political actors refusing to accept accountability for their crimes. —V.M.

50.

Evangelion: 3.0+1.0 Thrice Upon a Time (Hideaki Anno, Kazuya Tsurumaki, Katsuichi Nakayama, Mahiro Maeda, 2021)

The subtitle says it all: Thrice Upon a Time is director Hideaki Anno’s third attempt to put his boy-meets-robot franchise to bed after three decades. In many ways, he succeeded, rendering a long-awaited, electrifying vision of his apocalypse for fans of Neon Genesis Evangelion to dissect and fight over. Newcomers, however, will probably have their work cut out for them trying to parse the many secrets hidden between frames; this is a long-delayed movie that serves as both the finale of a tetralogy of newer Evangelion films and the remake of a divisive, series-ending film that in turn reimagined the also divisive final episodes of the original TV series. Thrice Upon a Time isn’t made for strangers, and it can sometimes feel as if it’s not really made for Evangelion’s die-hard fans, either. More than anything, it seems to meet Anno’s need to get ideas out of his own head. He and his creative team not only quote or meticulously reanimate individual shots from films such as The End of Evangelion, they also take the occasion to deconstruct the animation process itself. Giant robots duking it out in a city might literally slam through the wall of a cartoon “film set,” and the behemoths might suddenly find themselves people-size and squaring off within the confines of an apartment, before the fourth wall shatters entirely and Anno’s production miniatures and models are revealed. These sequences can be jarring and confusing but are simultaneously mesmerizing because they’re nestled into scenes in which the characters are finally talking through their decades of pent-up trauma. —E.V.B.

49.