Ebiri on Alien Artist H.R. Giger, 1940-2014

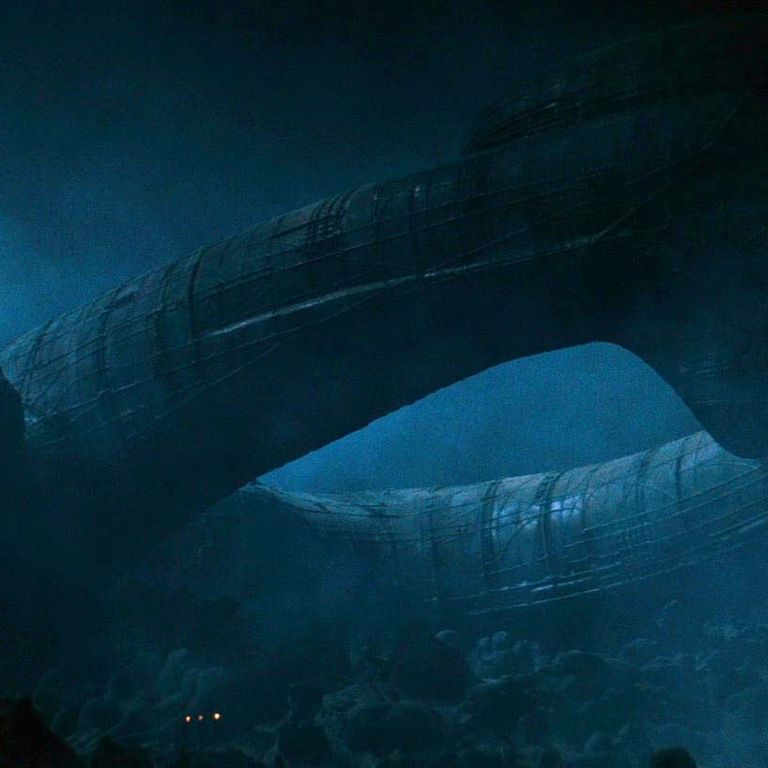

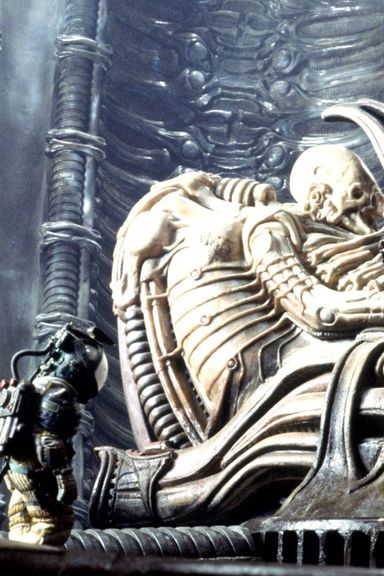

Over the course of his five-decade-plus career, H.R. Giger, who died yesterday, produced countless paintings, sculptures, interior decorations, films, books, and furniture designs. But of course, it’s the main creature from Alien for which he is best known today. And while this doesn’t do justice to his immense body of work, the importance of Giger’s achievement in that film cannot be overstated. Initially, director Ridley Scott and his producers fought the Fox suits who were worried that Giger’s work was too disturbing. (He helped design not just the infamous “xenomorph,” but also the “facehugger,” the “chestburster,” the derelict spacecraft, and the infamous “Space Jockey” remnant.) Here’s the thing: The Fox suits were right. The alien was too disturbing. It was the kind of thing that might have sprung from the mind of a tormented Swiss surrealist racked with night terrors. It was not the kind of thing you were supposed to find in a Hollywood studio blockbuster. It crossed a line. It was transgressive. And it immediately entered our nightmares, where it continues to kick around.

Giger had been brought onto the Alien project by writer Dan O’Bannon, with whom he’d worked on Alejandro Jodorowsky’s aborted film adaptation of Dune. The terrific recent documentary, Jodorowsky’s Dune, details the heroic efforts to get that film made, and it also unveils the various sci-fi movies made since the 1970s that “borrowed” elements and designs from Jodorowsky’s lost project. But an addendum could be made to its thesis, which is that a lot of those same films (and others) were likely influenced by the look of Alien. We talk often of how Star Wars and Jaws changed the movie landscape forever, but I think Alien should properly be included among those films as well.

And Giger’s creations are among the chief reasons why. (You can even see it in how the Star Wars films themselves went, in Return of the Jedi, towards the grotesquely elaborate, many-fanged designs of the Sarlacc and the Rancor.) After Alien, the more nightmarish, the more beyond-the-bounds disturbing creature and set design could be, the better. That’s because Giger’s biomechanical designs – fusing the organic and the metallic, the constructed and the evolved – clawed away at our subconscious fear of things whose origins we can’t quite pinpoint, which don’t seem like they could have been created by mere mortals. It was the perfect imagery for an era that saw the dominance of horror and sci-fi, and the rise of celebrity designers and effects artists who visualized the unknowable.

Of course, Giger had been creating such designs long before Alien – the Xenomorph is actually closely based on his print “Necronom IV” – and he would do so for years afterwards as well. He gained legions of fans, and his brand of imagery became a kind of pop-cultural cliché. There was a Giger Room at the Limelight club. There were Giger-branded guitars. Every heavy-metal band seemed to be “inspired” by him.

Still, the work remains pure. Look at Giger’s images in books like Necronomicon or in New York City, and you’ll sense a quietness at their heart that’s still deeply unsettling. They’re like transmissions from a world that’s left humans behind. I think it’s one of the reasons why, after all the album covers and signature bars and tattoos, Giger’s name has remained evocative, exciting. His images are both thoroughly other and yet, strangely familiar. Familiar not because we’ve seen them all over the place for the past several decades (though we have), but because even now, there’s something uncanny about them — like something we must have seen in a dream once as a child but tried desperately to forget. Even now, the work terrifies.