In a 2020 essay for the New York Times, the artist Christine Sun Kim described her “huge disappointment” at being asked to perform the national anthem in sign language at the Super Bowl, only for her performance to be virtually ignored by broadcasters. “Though thrilled and excited to be on the field serving the deaf community,” she wrote, “I was angry and exasperated.”

Anger and exasperation are at the core of “All Day All Night,” her new show at the Whitney. If that makes Kim’s exhibition sound like a kind of revenge on a society that has long passed over disabled artists, it is revenge at its most gripping. Deploying drawings, diagrams, musical notation, text, wall painting, and video, Kim explores how sound, silence, and oral language are social-political currencies that place the deaf at a constant disadvantage, in areas ranging from motherhood to politics.

In her Screen Real Estate for ASL Interpreters, little boxes connote how much room is given to the deaf on television broadcasts (there is an especially tiny one for “January 6th Committee on YouTube”). Suggested Amount of Friends to Sing Songs to a Baby is a grid of musical notes interspaced with lots of little P’s to signify pianissimo, or quiet. Suggested Way of Getting a Baby’s Attention by Waving Hands or Stomping on the Floor Instead of Using Voice is a graph of symbols that reveals how a deaf parent communicates with a hearing child. The titles alone are shocking in their bitterness and frustration, a way for Kim to make her feelings overt even in large black-and-white drawings done in a sketchy Saul Steinberg–ian hand.

There is a great video of Kim and her husband sandwiched together, front to back, facing the camera, in which one makes sign language and the other augments the signs with eyebrow movements, facial expressions, and changes of posture. In this and other works, you can hear a sardonic sort of laughter, laced with suffering. Alexander Graham Bell, the inventor of the telephone, appears occasionally as a satanic figure due to his advocacy for “oralism,” which favors lip-reading and speaking over signing and made communication for the deaf far more difficult.

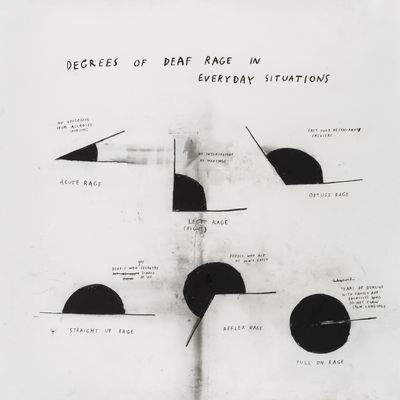

Degrees of Deaf Rage, first exhibited at the 2019 Whitney Biennial, may be her best work. Composed of six charcoal drawings of pie charts with captions, it aims between the eyes, and can change how you see the world of the disabled. The drawing titled Degrees of My Deaf Rage in the Art World has a caption that reads “Museums with zero deaf programming (and no deaf docents/educators).” Bard MFA, where she earned one of her advanced degrees, has a one-word caption that reads “Trauma.” Other captions read: “Fake terps at news conferences. Beyond rage”; “Being offered a wheelchair at the arrival gate”; and “Flight attendant leaves suitcase on the runway because when asked in spoken English no one claimed it.”

Kim takes her position as a spokesperson for the disabled seriously. In Access Rider, Kim prescribes how her work should be written about. “Please exercise sensitivity,” she says, citing “the oppression faced by the Deaf community.” She says critics who center her deafness are “reductive and othering,” as are those who use deafness as an “over-riding descriptor (deaf artist Christine Sun Kim).” Is this identity art? Only in the sense that all art, in stitching the contours and distortions of experience, is identity art.