Blame it on Andy Garcia’s smirk. Middle-school-aged me was minding my own business one Saturday afternoon, flipping through TV channels to distract myself from homework, when that man’s smile in The Godfather Part III made me reconsider my devotion to Leonardo DiCaprio and Rider Strong. They were boys! Andy Garcia was a man! That mischievous grin knew something, and I wanted to know it, too. There was knowledge hidden in his chest hair, contained only by an array of leather blazers. Costume designer Milena Canonero knew what she was doing, and may I extend my thanks to her yesterday, today, and always! How striking he looked, in both a red satin robe and a double-breasted wool suit.

The Godfather Part III was not a well-received film when it came out 30 years ago this month, but the passage of time and the recent release of a new Francis Ford Coppola cut in the form of The Godfather, Coda: The Death of Michael Corleone have allowed for a critical reassessment. Coppola’s conclusion to the saga of the Corleone crime family is driven by the same scheming, bloodshed, and complicated familial loyalty as the preceding classics, The Godfather and The Godfather Part II. Its ideas about guilt, regret, and redemption are well-considered, and Al Pacino’s performance drives home the weight of all this death — so much of it ordered by him. Diane Keaton’s Kay adds the skepticism and self-awareness the narrative needs to puncture any Scarface-like sympathies toward Michael’s myriad crimes, and Talia Shire transforms herself into a believable Lady Macbeth. The stuff with the pope is a little outlandish, sure, but haven’t the past decades shown us the lengths to which the Catholic Church will go to protect its own?

These are the reasonable observations one could make about The Godfather Part III and its saner moments. But there is one scene in this film that is so delightfully insane that it has captivated me ever since that Saturday afternoon viewing. One so melodramatic that it nearly derails Coppola’s otherwise-measured consideration of cause and effect, vengeance and revenge, and blood for blood. So scandalous that I really felt grown afterward; I did not tell my parents about the movie I wiled away my afternoon watching, despite both preceding Godfather movies being some of their favorites.

I am talking, of course, about the incest gnocchi.

The Godfather films consistently honor food as an integral part of Italian and Italian American culture. Vito Corleone, played by Marlon Brando in The Godfather and Robert De Niro in The Godfather Part II, runs an olive oil company as a front for the family’s other illegitimate dealings. In The Godfather, Clemenza teaches young Michael how to make pasta sauce with fresh tomatoes, sausage, and meatballs, with a little sugar as his secret ingredient. Cannoli are a training detail in The Godfather and a method of poison in The Godfather Part III. Oranges symbolize death, from the attempted assassination of Vito in The Godfather to his eventual death in the garden, and then again during the Atlantic City helicopter attack in The Godfather Part III. Bowls of spaghetti served by Carmela Corleone commemorate a new partnership in The Godfather Part II, while a birthday dinner for Vito at the end of the same film captures the deep fissures in the family decades later.

For the most part, how people find comfort and solace in food is treated thoughtfully by Coppola — which is what makes the sexification of these little pasta pillows all the more unexpected! The gnocchi incest scene comes about one hour into The Godfather Part III: Sofia Coppola’s Mary (indiscriminately aged — maybe a teenager, or maybe a 20-something?) is aware that her father Michael isn’t telling her the whole truth about his ailing health or the threats against the family, and puts on her best little skirt-suit and jaunty upturned-brim hat to visit her older cousin Vincent (Garcia). She’s already told her “cuz” that she’s had a crush on him for years, since she was 8 years old and he was 15 (“You haven’t kissed me ‘Hello’ yet. Relatives always kiss” is her flirtatious opening line when they meet again as adults), and there’s probably some unresolved daddy issues tied up in how drawn she feels to Vincent’s protection.

But Coppola — mercilessly maligned for her performance after stepping in for Winona Ryder (Entertainment Weekly published an entire piece about the backlash to her casting a month after the film’s release, featuring an interview with the actress and various gossipy complaints from cast and crew) — gives Mary a believable sense of innocence. Her line readings are wooden, but I’m willing to argue that tentativeness works for a character who has long been overprotected by her father, wrapped up in the safety that being his beloved only daughter provides. In the kitchen of Vincent’s club, though, Mary stops being his “little cousin” and asserts herself as the executor of her own desires. She is a young woman discovering her sexuality, and I’m sorry, who wouldn’t fall for a man who makes his own pasta?

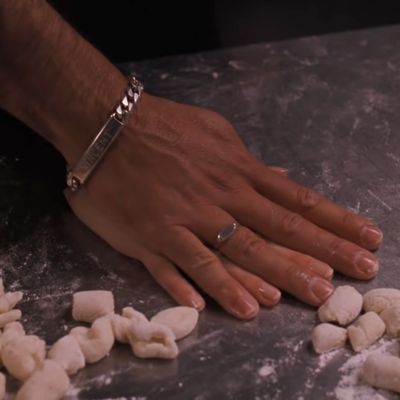

As Washington Post staff writer Phyllis C. Richman wrote in a January 1991 column about the film, “Vinnie makes gnocchi like an angel, with that masterful flick of the thumb that turns mere dough into tiny curled shells.” Standing behind Mary, who admits that she doesn’t know how to cook, Vincent takes her right hand in his, lacing their fingers together. Coppola stays on their bond, maintaining his camera in an unmoving close-up as Vincent guides Mary’s slightly cupped hand forward, using her middle finger to grab each little square of dough and roll it into the pasta’s distinctive shape.

They only last four gnocchis before Vincent splays their fingers out, rubs Mary’s hand, and transitions the vibe from hunger to thirst. They lean closer and closer together. A lean becomes a hug, and a hug becomes an embrace, and then a kiss on the neck becomes a kiss on the cheek, and then a couple of open-mouthed kisses become a full-on make-out session. Vincent’s “Let us cook” is fully forgotten once he carries Mary offscreen, and I am pretty sure what happens next would not pass any restaurant health codes.

So many inane details of this scene don’t quite add up. How many people was Vincent intending to feed with this gnocchi? He says it’s “for the boys,” but there’s only one other guy in the club. There are three pots on the stove, but only one of them has tomato sauce bubbling away in it. One of the other pots is probably boiling water for the pasta, but what is going on in the third? It looks like Vincent is using a fairly typical all-purpose flour to coat his workspace, and it seems like the gnocchi are made with a standard potato dough, but what about semolina for dusting? Ricotta for the mixture? (Did you know that the Family Coppola has their own line of dried pasta and jarred pasta sauce? I digress.)

These are nitpicky points, that, after years of rewatches, still haven’t turned me off of what The Godfather Part III does accomplish: the table-setting of a doomed romance as problematic as it is affecting. On the one hand, Mary and Vincent’s relationships is wrong; the two of them are first cousins who acknowledge their familial relationship with cutesy nicknames (Vincent calls Mary “cugina” more than once). On the other hand, The Godfather Part III frames their pairing as one of misguided, but understandable, passion. As part of the Corleone cycle of violence, they are doomed to a tragic end, but whatever tied Mary and Vincent together comes from a real place. Consider the kitchen seduction: Mary comes to the club for reassurance, but Vincent is the one who asks Mary to “hold me,” his fragility standing in purposeful contrast to her assuredness.

The real-life details of the scene (that 18-year-old Sofia was embarrassed by script supervisor Wilma Garscadden-Gahret, whom she’d known since she was 12 years old, encouraging her to put “saliva under [the] left ear” of 30-something Garcia) certainly diminish the cinematic effect. But the Vincent and Mary romance, even for all its flaws, is the tenderest part of The Godfather Part III — almost as soft as a warm bowl of gnocchi.