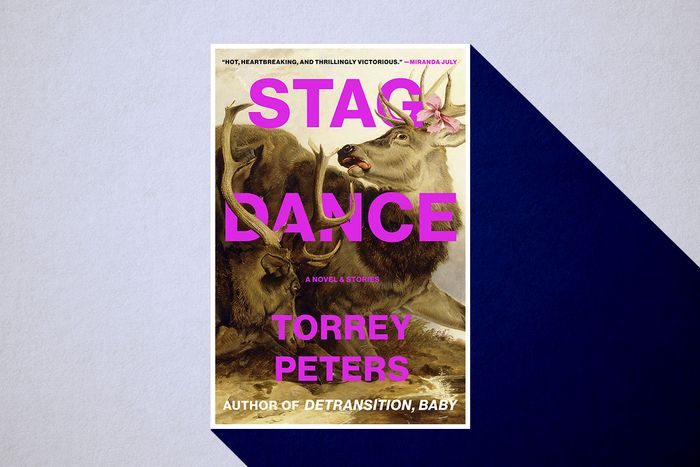

When Detransition, Baby came out in 2021, Torrey Peters called her debut novel a trans Fleabag. The book’s premise — a trans woman, her ex who has detransitioned, and the ex’s new girlfriend all contemplate raising a baby together — certainly has the makings of a TV show. The national best seller turned Peters into the latest de facto face of trans lit, though she had already been a major figure in the DIY trans-lit scene. Peters self-published short stories and novellas inspired by the erstwhile Topside Press, the indie publisher of trans and feminist fiction by such spiky writers as Imogen Binnie, Casey Plett, Cat Fitzpatrick, and Jeanne Thornton. Peters has used the spotlight to redirect focus onto many in this old guard. Now, two of her earlier works have been republished alongside new fiction in a collection called Stag Dance. Rather than being a straightforward novel about trans girls running around New York working through “gender feels,” validation, and “consent or whatever,” as Detransition, Baby’s Reese puts it, Peters’s new book chronicles a grittier aesthetic milieu. The titular story, the book’s longest, is a western set entirely before our modern conception of transness. The other three pieces run the genre gamut from romance to dystopian sci-fi. Notably, Peters seems to intentionally avoid writing into the “trans experience.” She examines the messy underbelly of DIY trans culture, diving into the cringier aspects of queer growing pains. The stories, jagged tales of sissies, losers, and assholes, showcase a more expansive palette and are written with sharp prose that crackles with transgressive glee.

Her collection asks the question, What if some people knew they were trans but refused to transition?

Take “The Masker,” reminiscent of Binnie’s Nevada, in which a young male narrator comes face-to-face with a trans woman named Sally and finds her life to be a cautionary tale rather than a heroic inspiration. While attending an event for cross-dressers, the narrator tries to cruise but keeps running into Sally, whom he views as a tragic prima donna. The Out magazine honoree is a nag, just someone in the way of a good time. Sally wants to be the narrator’s mom, but the narrator wants to hang out with a mysterious chaser wearing a black mask. But he bristles at a trans woman’s description of The Silence of the Lambs — a bleak psycho-sexual fate. Instead of digging into his possible gender dysphoria, the narrator dissociates, envisioning himself hovering above his body even as he goes through the motions of sex with the masked bandit. By exploring gender through such fractured mirrors, Peters pushes her fingers into the wounds budding queers are desperate to hide.

Stag Dance features many characters who seem to be repressing their attraction to trans culture. Does this actually make them trans? Maybe, maybe not. In the title story, a lumberjack wants to playact as a woman in a bizarre ritual during which men vie for one another’s attention by pinning a cloth triangle to their groins. Once the game’s begun, the men challenge each other to win over the “women.” To be a woman is the least desirable social stratum in this world of masculine grandeur — yet some wish to be punished. These men chopping down wood in the backcountry are locked into the performance of manhood even as they become jealous of the men who choose to masquerade as women. For men new to the allure of femininity, being pursued is intoxicating. Still, it’s not as if the effeminate lumberjacks are treated well. Bottoms compete for their favorite butch’s attention even as they face crude bullying. Wanting to be a woman is an extremely punishable act.

The prose in this story is smooth like slate, devoid of any modern references to movies, technology, or gender as we now envision it. Long passages of natural description set the scene as we encounter “the whole of creation preened in bridal finery.” By setting Stag Dance in a world long before the internet, Peters explores the chasm between what her narrator wants and what he actually has access to. The narrator frets over his looks even though “no mirror had ever befriended” him. As soon as he pins the triangle to his crotch, he becomes a target. Shrugging off debates over the idea of trans ancestors, Peters explores the untenable, crunchy feelings that arise in a society organized by masculinity. Options are limited for our tender lumberjack. He must make do with being a secret, living as an unacknowledged lover for the head of the pack. Without resorting to modern terminology, Peters is just as adept at looking at how those without access to trans identity explore gender.

Meanwhile, “The Chaser” features two male students at a Quaker boarding school trapped in a vicious love affair. The narrator is obsessed with what is “super gay” and what is “hetero.” He also has a tortured crush on his roommate, Robbie, a boy who easily befriends girls and seems to accept his own sexuality without any qualms despite being tyrannized by his peers. The narrator, however, soon discovers he enjoys sleeping with his bunkmate. There is, in fact, a deep well of lust underneath his homophobia, the kind that’s all consuming. At first, it’s easy to do one thing in public and another in private, but the narrator is quickly overcome by shame, feeling like a “cock-desperate fag who deserved rejection.” After the narrator steals a nightie from the laundry room and asks Robbie to wear it, the affair’s power dynamic shifts. It’s an intimate act of rebellion. Suddenly, Robbie owns him. There’s a secret that could destroy the main character’s social standing. So he ignores Robbie. The narrator is too afraid of paying the cost for loving a boy. Shame is his portal, another glimpse into the crossroads of sexuality and gender. Peters dives headfirst into these negative outcomes — those who could have been liberated by desire but choose to drown rather than swim. Some sink. But this doesn’t erase their gender deviance, merely complicates it. There’s a romantic pang to these characters not quite reaching their full potential.

Pigs abound in these tales. Peters draws a parallel between the animalistic instincts of such beasts and queer people prone to confusing predators for lovers. The narrator is a pig keeper in “The Chaser.” Elsewhere, in “Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones,” porcine critters offer an alternative form of hormone-replacement therapy. Testosterone-fueled ranchers harvest third-rate estrogen from hogs and sell it on the black market. “Infect” offers a trans read of the apocalypse through a world in which many people inject low-grade estrogen and are known as “auntie-boys.” The narrator is flailing, doing grunt work after a mysterious event has turned the world into a wasteland. How possible is solidarity when everyone’s grasping over a dwindling stockpile of resources? The narrator’s ex Lexi is the one who initiated the event, draining everyone of their natural hormones using a man-made contagion that quickly spreads from Seattle across the world. Before the hormonal apocalypse, the narrator struggles to maintain her toxic dynamic with Lexi, ultimately breaking up with her and being ostracized by the very community she once hoped to be part of. Only after the apocalypse do they reconnect, becoming comrades rather than lovers. While at times pessimistic — describing the group as “a coven of trans women polyamorously fucking each other to biblical levels of drama over the soundtrack of Skyrim” — Peters ultimately ends the story in an optimistic place. This isn’t to say the vigilante trans group in the new world is free of petty catfights. Any sustained group dynamic is a hard-won affair, full of strife and discord. One of the trans separatists in “Infect” warns the narrator that any naïve optimism is misplaced: “Do you think the words trans women and utopia go together in the same sentence? … We’re still bitches. Crabs in a barrel … We aim high, trying to love one another, and then we take what we can get.” This is the ache and triumph of Peters’s fiction, the ability to strive for more even as we disappoint each other over and over again. Across Stag Dance, Peters refuses to play into the modern, overly determined motivations of contemporary fiction, instead harnessing a technique she calls “strategic opacity” as a way to access characterization not dependent on Psychology 101. The term originally refers to a lack of obvious motive in certain Shakespearean characters like Hamlet and Iago. Some actions cannot be reduced to simplistic internal incentives. Detransition, Baby’s Reese wants to be a mother just because she does. A lumberjack wants to be a woman just because he does. Gender, like art, Peters argues, is not always explicable. The choices we make on a whim can sometimes say more about us than our most calculated attempts at coherence.

More Book Reviews

- The Minority Report Gets a Trump-Era Update

- Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Frustrating Return

- Neko Case Survived It All