It’s cold as hell in Ennis, the fictional Alaskan city that serves as the backdrop for True Detective: Night Country. Most of the season takes place in the “polar night,” a monthslong winter period when the northern orientation of the state means the sun never rises. That overwhelming darkness amps up the horror of the new season while unspooling a mystery involving frozen scientists, a murdered Indigenous woman, a shady mining company, and … malevolent spirits? As we follow Liz Danvers (Jodie Foster) and Evangeline Navarro (Kali Reis) into the creepier corners of Ennis, it’s hard not to sweat through the frost.

“It’s seriously inhospitable,” says production designer Daniel Taylor, reflecting on his research trip to Alaska that inspired the season’s filming in Iceland. (The Nordic country provides extensive infrastructure to support film production, a sizable tax credit, and a relatively temperate climate that was easier for the crew to deal with — though routine warming breaks were still needed.) “We were only there for a few weeks, but it was enough to get a sense of how hostile and desolate it is, how terrifyingly dark all the way through.”

One of True Detective’s signature elements, aside from grizzled protagonists navigating winding plots, is the atmospheric strength of its locales. Season one sweltered in swamps that underscored Louisiana’s gothic horror; the industrial brutality of Vinci, a tiny city modeled after real-world Vernon, California, made the largely reviled second season feel infinitely more interesting; and the harsh terrain and dusty colors of season three’s Ozarks offered a reasonable place to work out some demons. So it is with Night Country, which sees writer-director Issa López taking the reins from series creator Nic Pizzolato to move the action deep into coastal Alaska, where winter temperatures in the long night can dip to between -4 and -23 degrees Celsius. “What we wanted to do for True Detective is base ourselves in an environment that feels real and authentic and Alaskan,” says Taylor. For the most part, that meant exporting their vision to Iceland and reconstructing it with the resources they found there.

Finding Ennis

Taylor drew heavily on a reconnaissance trip to Anchorage, the state’s most populous city, as well as two coastal cities further north, Nome and Kotzebue, which played huge roles in defining the isolated feel of Ennis. The cold looms over everything; Taylor recalled removing his glove to photograph the frozen Bering Sea when it was -35 degrees Celsius and feeling the blood in his fingers start to solidify. That research led Taylor’s team to pick up quotidian details underscoring how life works in such a difficult climate. People leave their car engines running when they pop into the grocery store because the fluid would instantly freeze otherwise; if a person isn’t expected to live through the winter, they prepare by getting their graves dug before it starts to get cold and the soil can no longer break.

It’s difficult and expensive to transport goods to such remote locations, especially in the winter, so residents frequently reuse construction material. “The main streets were this hodgepodge of different buildings built in different sizes at different years with different types of cladding,” says Taylor. “Nothing gets thrown away in Alaska. That was a theme we wanted to latch onto: a resourcefulness, a desolation, this idea of broken things tied together.” In Iceland, production set large swaths of Ennis in Davlik, a village to the north of the country, and Keflavik, a town not far outside Reykjavik that happened to be home to an old American military base. That base turned out to be a boon for production because its buildings possess a distinctly American look, down to the doors and fixtures, as opposed to a European one. “Fully rebuilding houses would be a touch too much,” said Taylor.

Housing the Locals

Homes make up some of the more interesting spaces in Night Country, since they serve as the primary means to insulate from the cold — and express the nature and stature of a character. Chief Danvers, for instance, lives in a building that looks every bit your prototypical suburban American home: two stories, white façade, garage on the side, and a flagpole complete with a frozen, flapping American flag. “We felt like her rented accommodation as a police chief would be slightly more aspirational than others in town,” said Taylor. “It’s a brittle, kind of colorless representation of her character.”

A more colorful take on home as an expression of character belongs to Rose Aguineau, played by Fiona Shaw. One of López’s earliest reference points for Aguineau was Michael Caine’s character in Children of Men, Jasper Palmer, a former political cartoonist and friend of Theo Faron (Clive Owen) who maintains his optimism in the face of the apocalypse. Jasper lives off the grid in a gorgeous modernist house full of books and ephemera; that building features a huge window that looks out into the forest, similar to Aguineau’s smaller window that gazes out into the dark blue expanse. Cramped and lived in, her space is bursting with fabrics, art, and endless rows of books that populate rickety open bookshelves (made of driftwood brought in for production) lining the walls. “We wanted it to be quite warm inside,” said Taylor. “When you’ve got those tremendous blues with the snow outside, it’s always lovely to balance it with slightly more rustic terra-cotta, auburn colors.”

To further flesh out the space, the team worked closely with Shaw, who drew inspiration from Dorothy Cross, an Irish artist and personal friend. Cross’s art routinely deals with the ocean and the natural world, and like Aguineau, she’s also a mix of academic and artist. Cross’s workspace, which you can peek at in this video, informed the choice to dress the living room in a way that trends closer to an art studio, with crafts, gems, and fabrics tastefully strewn about. Aguineau’s house was also one of the few occasions where Night Country shot entirely on location. The home apparently belonged to two Icelandic sustainable farmers, whom Taylor described as “basically Rose from 20 years before.”

Policing the Town

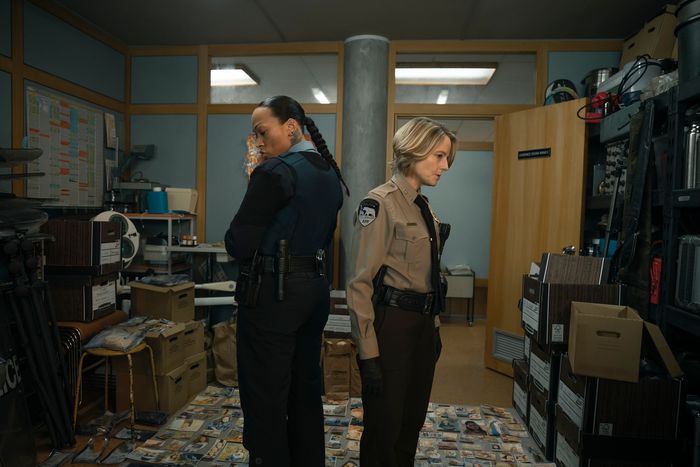

You can’t have a detective show without a police station, and almost as a rule, those settings are drab, Brutalist affairs. Recall the room where Martin Hart (Woody Harrelson) and Rust Cohle’s desks are situated in the first season: a colorless, cluttered space drenched in depressing fluorescent light. Though life-sucking in its own way, Night Country’s police station has a touch more character. Since the series takes place around the end of the year, holiday décor like garlands and a small, sad Christmas tree appear throughout the office, which features the warm lighting you’d expect from people who know how to deal with the polar night.

Drawing once again from the notion of reuse in remote Alaska, a throwaway line in the script reveals that the station is housed in an old dentist’s office. (In real life, these exteriors were shot using an old post office in Davlik.) Taylor scattered props that point to the building’s previous life throughout. “There’s an old dentist’s sign outside that I didn’t light up so people who see it could think, What the fuck?” said Taylor. In the third episode, when Danvers and Navarro hole up in a smaller room to sort through evidence files, you can spot an old dentist’s lamp shoved in the corner. “Issa wanted the audience to sense that it’s a two-bit police department,” he said. “They’re not the best.”

Constructing Tsalal

For the Tsalal Arctic Research Center, the suspicious science facility that kicks off the mystery of Night Country, Taylor brought in a glaciologist, Robert Mulvaney, to help with the layout of the building, explaining how the scientists populating Tsalal would move through the space. In the opening sequence, the camera floats through in a manner that reflects the usual rhythms of life: There’s a gym, a laundry room, a kitchen, a recreation room where Ferris Bueller’s Day Off is playing. “You want it to excel in its normality,” said Taylor. “If it was too much like a horror house, that would be distracting.” Hence the amount of clutter and everyday detritus: Post-it Notes and flyers line the walls of the living spaces, as well as bookshelves of varying orderliness. The laundry room is bursting with towels, napkins, and cleaning supplies — you can practically smell the detergent.

With the exception of some portions of the exterior, Tsalal was built on a soundstage, and the set is said to be the largest in Iceland. For the design team, the challenge was to find a middle ground between the excessively futuristic and a retro-’70s look, which at this point is an aesthetic cliché owing, perhaps, to the popularity of The Thing, the John Carpenter classic now synonymous with paranoia around arctic research centers. “I really liked the idea that you never could see what was coming around the corner,” said Taylor. “There was also kind of a degree of jeopardy because you couldn’t quite anticipate what was about to happen.”

For the exterior, the production team studied various real-life research facilities around the world, eventually developing a particular fascination with the saucer-shaped Igloolik Research Center. Circular designs seem to be common with fancy, high-tech structures these days (the Sphere in Las Vegas; the Apple Park campus’s giant ringlike shape, which earned it the nickname the “spaceship”). Circles, of course, are also a key motif in the broader True Detective mythology. Matthew McConaughey’s Rust Cohle utters the much-memed line “Time is a flat circle,” and Night Country shares the first season’s obsessions with spirals. “It’s the idea that insanity is a circle,” said Taylor, speaking to the shape’s thematic contribution. (“It’s probably why the Apple campus is like that,” he jokes.)

Fishing on the Ice

The third episode sees Danvers and Navarro track a suspect, Oliver Tagaq, to an Indigenous fishing village somewhere outside Ennis. An open encampment almost completely exposed to the elements, the village is made up of tents, scrap, and two derelict huts. Whenever they sought to develop a primarily Indigenous location, Taylor’s team worked closely with Cathy Tagnak Rexford and Princess Daazhraii Johnson, two Indigenous producers from Alaska. Rexford, a poet and playwright, and Johnson, whose production credits include Molly of Denali, also assembled an advisory council to weigh in on matters pertaining to production and the narrative. (When Danvers and Navarro meet Tagaq in his hut, he refers to the village’s being on Iñupiaq territory.)

“We would have a kickoff meeting with Princess and Tagnak where we would talk about what exactly we were doing, how we were doing it, and where,” said Taylor. “We would run a loose dressing plan past them — a mood board of a selection of props we thought would be appropriate. Usually, they would give us a load of stuff they thought would be worth sourcing and introducing. Then we would build it and dress it.” They also worked with Sarah Whalen-Lunn, an Indigenous artist, to create the design for more granular details like tattoos, signage, and paintings.

The village was constructed in an old gravel pit mine not far from the location where production staged the discovery of the corpsicle. “They leveled off an area we imagined was the seas just beyond,” said Taylor. “It went for miles and miles through the valleys, and we were implying that the sea was only just over the way.” The two derelict huts were found during shooting of the mine-gate protest at another location and were loaded up on a truck, driven up the mountain, and unloaded at the gravel pit, after which they were left to sit for a few months so snow would naturally build around them. “That photographed spectacularly,” said Taylor. “When you see the cops come up and those guys drift across to them with the dogs, there’s a sinister, hostile feeling.” That vibe deepens when Navarro returns with Pete, a younger cop played by Finn Bennett, in the next episode and finds Oliver’s hut abandoned, the suspect having left behind a frozen bowl of soup.

Thawing the Corpsicle

After discovering the corpsicles of the missing Tsalal scientists, Chief Danvers turns to the local ice-skating rink, an establishment owned by the town’s shady mine, to thaw the huge, frozen block of scientists in such a way as to avoid compromising the forensic results. The venue is actually a real ice-skating rink in Reykjavik called Skautahöllin í Laugardal in Laugardalur Valley, an area to the east of the city known as a popular hub for outdoorsy recreational activities. Over several episodes, Danvers and Navarro routinely return to the mountain of flesh at the center of the rustic ice rink, a grotesque sculpture that cuts a fun contrast to the venue’s family-friendly origins. The building’s festive décor also contrasts with the macabre; holiday lights hang from the rafters, and Christmas trees pepper the grounds. There’s even a tree on the ice, which sticks around as an amusing accompaniment to the frozen scientists. “I like that we dressed the venue in a Christmas tree,” says Taylor. “The juxtaposition with the bodies is such morbid fun.”

More From This Series

- Vulture’s 25 Most-Read TV Recaps of 2024

- The Best TV Shows of 2024

- How Did Best Song Become the Year’s Most Exciting Emmys Race?