When I moved to New York in 1980, most artists lived in Manhattan. For some time now, the bulk of the artists in the city have lived and worked in Brooklyn. Still, so much of the art world remains attached to Manhattan and its money that it feels like Brooklyn is but a satellite orbiting the gleaming cluster of galleries that stretch from Chelsea to the Lower East Side. Decades after rising rents and gentrification pushed artists to the outer boroughs, it remains unclear who or what, exactly, a Brooklyn artist is.

Brooklyn’s eternal secondary status is epitomized by the Brooklyn Museum, located at the crossroads of Eastern Parkway and Flatbush and flanked by Prospect Park. The museum houses over 140,000 objects in its 560,000 square feet, but it is not quite the encyclopedia of art history that is the Met, whose $374 million annual operating budget dwarfs the Brooklyn Museum’s budget of $61 million. Everything at the Brooklyn Museum is done on a shoestring. What’s more, there’s a pent-up yearning for this museum to be more than a museum, to capture the artistic energy that is bubbling up everywhere across the borough and refine it into something discrete and new.

To mark its 200th anniversary (who knew an American museum could be this old?), the museum is hosting “The Brooklyn Artists Exhibition,” a baggy, uneven show that features both the institution’s strengths and weaknesses under director Anne Pasternak. On the one hand, we have a museum that is far more open than its counterparts to embracing the city’s changing demographics and questioning hegemonic historical narratives. On the other hand, the art itself doesn’t amount to a distinct ethos or spirit that animates each of the great museums in Manhattan. The artists may technically live or maintain studios in Brooklyn, but they could really be from anywhere.

The show is salon meets flea market — a beautiful mess bombarding you with stuff. In one entrance are the abstract paintings of Tamara Gonzales and Yevgeniya Baras, and in another the graphic fantasies of Chitra Ganesh and Jackie Hoving. The first gallery is a mash-up of everything: old-school Brooklynites like Michael Ballou (whose wobbly vase I mistook for Yves Klein) and Sam Messer (a bumpy painting of a typewriter) are cheek by jowl with Leah DeVun’s quietly compelling photograph of a trans parent at home, Jason Bard Yarmosky’s painting of identical twins, and the architecturally inspired paintings of Jane South. It’s a great cement mixer of styles, materials, processes, mediums, and approaches.

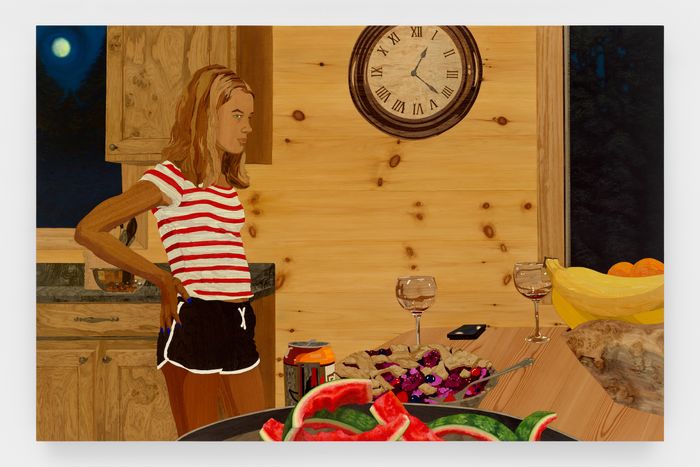

There’s a lot of controlled, craft-based art. Rather than individual artists, the sheer varieties of forms and ways of making are the real stars here. But overall the visual tropes feel familiar, be they geometric, biomorphic, or abstract. There’s a lot of the requisite figurative work painted from life, much of it deadeningly photorealistic. As for subject matter, there are a lot of contested bodies from many identities and sub-groups. We get ideas of urbanization, ecological decay. Were we to read the backstories of much of this work, we would learn it was socially minded.

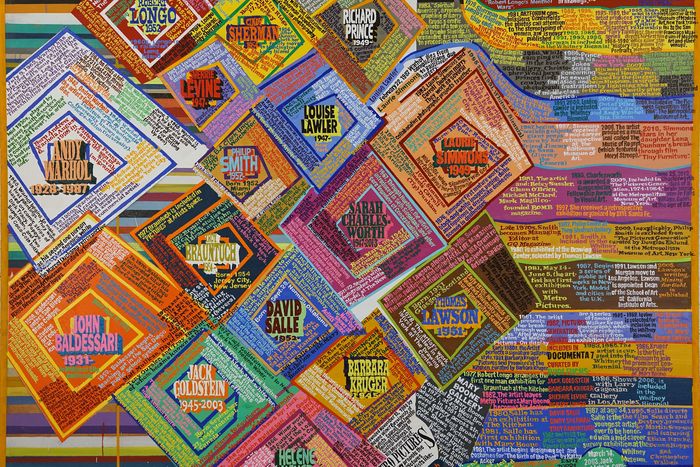

A handful of pieces stand out. My favorite thing here unfortunately has a sound component. This is Ruby Chishti’s In the City of Children, a large sculpture made of recycled clothes, thread, wood, wire mesh, and steel, charged with lost dreams and a forceful presence. Not to be missed is the insane marquetry painting of Alison Elizabeth Taylor, in which different types of wood are arranged to look almost seamless. Also great is Nancy Grossman’s powerful Untitled, (Red Fez), dated 1967–2016, an assemblage of metal, rubber, fabric, and leather mounted on canvas. And then there is Loren Munk’s wildly colored painting of a map with text that recounts the galleries of Soho — perhaps an inadvertent nod at the gravitational pull of the Manhattan art scene and its wealthy patrons. All these artists deserve more exhibition attention.

As I perused this eclectic undertaking, I thought about how more and more artists have moved further away from artistic centers like New York, as the economics have made living here (even in Brooklyn!) impossible. As long as artists surround themselves with other artists (a must, in my book) and see shows in cities every so often, they don’t need to be in New York per se. Which perhaps is what the migration to Brooklyn was all about anyway: Rather than establishing some new frontier in New York art, it was the first step toward leaving New York for good.