This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

For a solid decade, Whoopi Goldberg was the funniest woman in America.

Along with her two best friends in Hollywood — Billy Crystal and Robin Williams — she ruled the 1990s and, in so doing, expanded notions of what a Black woman could be in Hollywood. Whenever the three appeared on a stage together, it was appointment TV. They had chemistry as a trio of troublemakers. Crystal the wisecracker; Williams the frenetic, unpredictable master of impressions; and Goldberg, the crackling mischievous wit who had everyone’s number and wasn’t afraid to use it: the Clintons, Heidi Fleiss, Bob Dole — you name ’em, she had a joke about ’em.

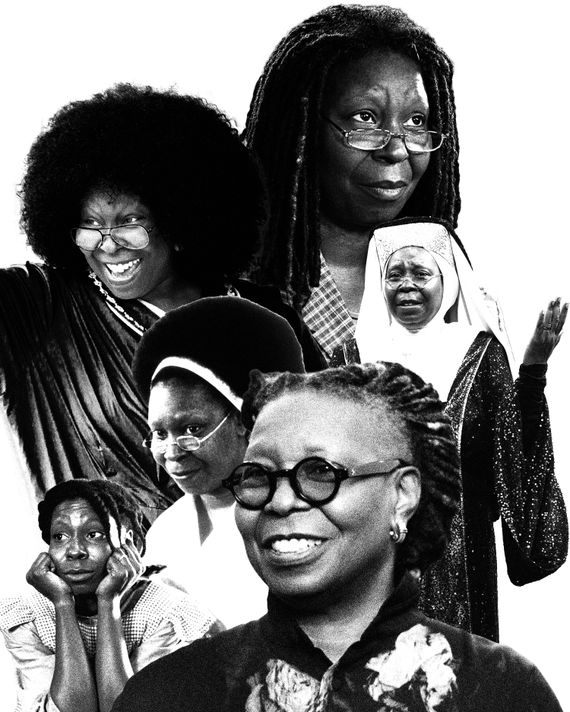

To tumble down the YouTube archive of Goldberg’s career is to marvel at the stage presence of a dreadlocked woman with no eyebrows who held Hollywood in the palm of her hand every time she hosted the Oscars. She was the cool girl, born Caryn Elaine Johnson and raised in New York, who actually got to do things her way, up to a point.

On paper, it seems difficult to quantify what made Goldberg, now 64, such a star. Like Williams and Crystal, she was prolific and often the centerpiece of movies that would likely not stand up to the tastes of a more demanding and discerning 2020 audience. Remember Corrina, Corrina, in which she played a maid helping a little white girl and her father grieve the loss of their homemaker mother while falling in love and fixing racism? How about Ghost, the film for which she won an Oscar playing a magical Negro communing with a dead Patrick Swayze? Or Clara’s Heart, in which she’s the Jamaican helpmeet to a rich white family?

Perhaps those projects elicit grimaces as a whole, but more often than not, Goldberg made them sing, especially if they required a rapid-fire delivery of dialogue when she got good and revved up to chew someone out — like the moment in Sister Act when Bill Nunn’s detective character, Eddie Souther, blithely tells her she’s going to have to enter witness protection in a convent until her murder-committing mob boyfriend can be apprehended. She was a singular talent in a business that didn’t know what to do with actresses after they turned 40 and really didn’t know what to do with a dark-skinned Black woman who defied white beauty standards when Black actresses who looked like Halle Berry and Vanessa Williams were in vogue. That singularity is evident in her EGOT status; she’s the only Black woman in history to have nabbed each of the major award statues, and she did it with a handicap. Goldberg never did get to be an ingénue, having broken out in 1985 by playing Celie Johnson in The Color Purple at age 30. But what Goldberg apparently lacked in light skin and straight hair, she more than made up for with comic smarts and an undeniable screen presence that sprouted, naturally and without effort, from that signature, cigarette-flecked rasp of a voice.

The capstone, the true pearl of all her onscreen efforts, of course, is Celie. It’s one of the few films that really marshals the potential that came bursting through her 1984 one-woman show, Whoopi Goldberg: Direct From Broadway, which she initially developed and performed under the title The Spook Show. Goldberg moved through a menagerie of characters à la Moms Mabley: a Valley girl, a drug-addicted thief, a hobbling old woman, a little Black girl who hasn’t yet discovered the gems within herself and so pretends to be blonde and white by throwing a towel over her head. Direct From Broadway is a comedy and it isn’t. In her first big write-up in Vanity Fair, the one accompanied by Annie Leibovitz’s portrait of Goldberg as the metaphorical fly in a tub of milk, Susan Mingus (widow of Charles) summed up its unexpected depths: “I came expecting comedy,” Mingus said. “She’s deadly serious. She’s not a comedian. She’s a philosopher. Or a saint.”

In The Color Purple, Goldberg deploys that skill for creating a character who withdraws deeper and deeper into herself to dissociate from the daily abuse she receives from her husband, Mister (Danny Glover), who acquired her in much the same way a man might acquire a mule. It is literally the story of a woman discovering her voice after she’s been told she’s worthless and ugly and that her worthlessness and ugliness is a direct result of being born a Black woman. The turning point of the film is a study in queer subtext; the light begins to shine within Celie when Mister’s girlfriend, Shug Avery (Margaret Avery), turns her attention and kindness to Celie. It’s a scene that relies on Goldberg’s control; a slow, shy smile creeps onto her face, and her instinct is to hide it behind her hand because the warmth and glow of Shug’s attention is almost too much to bear. That scene alone should have won her the Oscar, but instead she won it for playing Oda Mae Brown in Ghost.

In films where she’s given the time and real estate to tackle more challenging themes, like she was able to do in The Color Purple, Goldberg shines, even when the material is less serious. Sister Act, How Stella Got Her Groove Back, and The Associate remain timeless because their subject matter is timeless, too. In Sister Act, she’s an underappreciated Reno lounge singer with an irrepressible love for Motown and an inability to simply fade into the background, even when her life depends on her doing so. She elicits guffaws as the unapologetically horny friend seeking a hookup in Jamaica in How Stella Got Her Groove Back, then elicits tears when it’s clear she doesn’t want to spoil the fun of her best girlfriend’s May-December relationship by revealing a diagnosis of terminal cancer. And in The Associate, she embodies the frustrations of being an intelligent striver whose career growth is stymied not by ability but by gender, so she decides to create an imaginary white male business partner when she isn’t taken seriously on her own. (That last circumstance, by the way, is one that two real-life women enacted in 2017 for the same reasons.)

In a just world in which actresses were not given a Last Fuckable Day expiration date, Goldberg would have been tapped to co-star in a series of buddy comedies with her Sister Act and Rat Race co-star Kathy Najimy. Surveying her post-2000s work can be frustrating — when she’s not doing voice work, she’s shuffled into roles as post-menopausal aunties like the one she plays (whose name is Moms) in Furlough or Raynelle Slocumb in Kingdom Come or Lola in Nobody’s Fool. A bit in Terence Nance’s Random Acts of Flyness provided a too-short return to the sort of oddball irreverence where she shines brightest (“Don’t touch the pussies, please,” she admonishes in the episode. “Those are not your pussies”).

If there’s one actress who has inherited a smidge of Goldberg’s comedic legacy, it’s Tracee Ellis Ross. Ross lights up award-show hosting gigs with a Goldbergian embrace of the ridiculous — one of two elements that made watching Goldberg’s Oscar-hosting stints such fun. (The woman painted her face white and opened the 1999 ceremony fully dressed as Queen Elizabeth I, then returned after the commercial to retort, “Who knew it was this hard to get a virgin off your face?!”) The other element is what puts Goldberg in a class of her own. She had a knack for telling truths about white Hollywood to its face and delivering them with zero remorse (truly, the whiteness of those 1990s Oscar audiences is a sight to behold) and without the meanness that characterizes the acts of Ricky Gervais or Seth MacFarlane. And often she did so at great risk to her career; she was first and foremost an actor who worked within the system, not a titanic producer calling her own shots. Often, when she made everyone laugh, she was talking shit about potential bosses.

These days, Goldberg has settled into a stint as co-host of The View, the referee of a rhetorical daytime lady cage match in which she is likely to bust the myths trotted out by conservative blondes like Elizabeth Hasselbeck and Meghan McCain. One can imagine her film work finding new life among the lip-syncing TikTok set. (Even if she doesn’t, a single phrase, “Molly, you in danger, girl” will forever live on in GIF infamy.) She is still making new projects — she stars in a forthcoming CBS All-Access adaptation of the post-apocalyptic Stephen King novel The Stand. Will it matter if it’s any good or if she’s any good in it? Probably not. That rasp, those locs, that wit — they’re indelible.

Soraya Nadia McDonald is the culture critic for The Undefeated. She was a finalist for the 2020 Pulitzer in criticism and the winner of the George Jean Nathan Prize for dramatic criticism.

*A version of this article appears in the October 26, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!