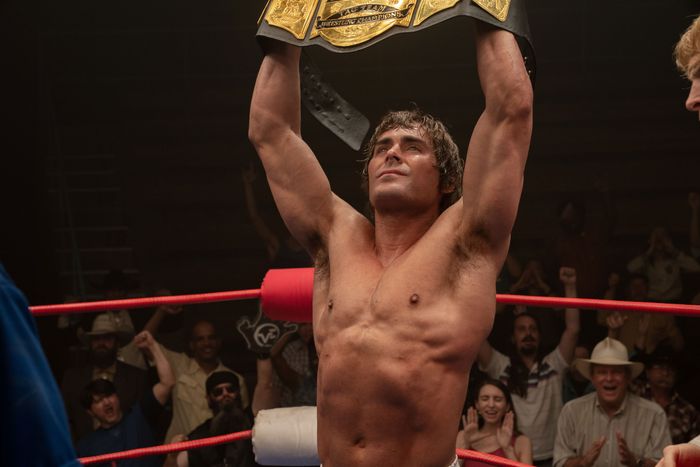

When Zac Efron first appears in The Iron Claw, the sheer bulk of him is enough to make you gasp. Nearly 20 years ago, when Efron shimmied his way into public consciousness as Troy Bolton, the lithe heartthrob of Disney’s High School Musical, his bright-eyed, puppy-dog appeal and nimble dance moves clinched his teen-idol fame. Seeing him now — puffy and encased in muscle; his jaw comically pronounced after injury-related reconstructive surgery — might come as a shock for anyone who holds on to the image of Troy. Yet the power of Efron’s performance in The Iron Claw has little to do with transformation, at least not the kind that actors like Efron’s Disney Channel contemporary Austin Butler undertook when he “transformed” into Elvis. We don’t question whether his mannerisms or speech patterns echo that of the real Kevin Von Erich, because Efron lays bare the only surviving Von Erich brother’s deepest wounds — and he does so by exerting the force of his own personality.

Efron is never not himself onscreen. He has that in common with the greatest stars. Cary Grant, Jack Nicholson, Tom Cruise — no matter the genre, wig, or weight gain, these actors could never be eclipsed by their characters; their essence shines through the artifice, making it real from the inside. Much of Sean Durkin’s wrestling drama is spent watching Efron sprint and lunge and throw himself into the air, but when the camera pulls in to his face, there’s the Efron we’ve known: his blue eyes edged with the same soulful naïvete that made him so convincingly romantic in youth. It’s that boyish charisma that anchors the film’s tragedy. It reminds us that beyond their physical powers and brawny exteriors, the Von Erich brothers were barely grown. Efron embodies the crisis of a man whose innocence is exploited in gruesome, unimaginable ways.

The Iron Claw introduces Kevin as he’s climbing out of bed in his tighty whities. The camera centers his abnormally ripped body, but the moment is tainted by a feeling of unease rather than awe at his sculpted physique. Kevin is an adult still living under his father’s roof and sleeping in a too-small bed in a room he shares with his brother. At first, there’s something joyous about his arrested development. When we see him zooming through a field, dutifully starting his day with a bit of cardio, Efron’s eyes give off sparks of ecstasy. Kevin is thrilled by his own abilities like a kid who’s switched bodies with Superman. It’s no wonder the eldest Von Erich brother gravitated so early to his father’s profession. Being in the ring is the closest he can come to flying.

When we meet the Von Erich patriarch, Fritz (Holt McCallany), this fantasy is put into perspective. Here is a man whose self-worth is premised on retrograde standards of masculinity, manifested through a blind obsession with athletic success. Denied the World Heavyweight Championship title at the height of his own wrestling career, Fritz has internalized the sport’s macho theatrics: strength, both physical and performative, is to him the greatest measure of character, and his sons are mere heirs whom he ranks with a straight face. Raised under these conditions, Kevin’s exaggerated musculature isn’t intimidating; it feels like overcompensation, a bid for his father’s approval.

Efron has spoken publicly about his experiences relying on intense, borderline-unhealthy workout and diet regimens to maintain his sobriety, and gossip peddled by tabloids and the terminally online has contributed to an invasive obsession with the actor’s body. From criticism of his dehydrated Baywatch (2016) abs to his so-called dad bod in the travel docuseries Down to Earth (2020), that fixation with Efron’s physique has hounded his transition from adolescent to adult star. This fraught history seems to color the self-consciousness that Efron brings to the screen. Kevin isn’t a strutting peacock so much as he seems to be hauling a load, always checking that what he’s carrying is satisfactory.

Kevin may be the beefiest son, but he’s Fritz’s second favorite after Kerry, played by Jeremy Allen White with a slick, leonine intensity that more readily commands respect. Kevin is knocked down yet another rank when David (Harris Dickinson) is initiated into the sport. The younger brother overtakes the more seasoned Kevin because he’s a natural performer, better at shit talking and chest puffing before an audience. When Kevin is recording a promo reel for an upcoming match, you can see the gears turning as he tries to act out a cocky stage persona — the special sauce in wrestling’s orchestrated soap opera. He stumbles through his lines. Efron exudes sincerity in this moment, the same quality that allows him to pull off grandiose emotions in movie-musicals. Here, he uses it to highlight the tenderness and self-doubt that bar Kevin from convincingly monologuing about imaginary rivalries and ass-beatings.

Kevin is more at ease in passive roles, be it following Fritz’s orders, playing wingman to his brothers’ teenage shenanigans, or allowing his future wife, Pam (Lily James), to take the lead. When Pam approaches him after a match, she coquettishly takes him through the steps of asking her on a date. Efron’s eyes are avoidant and hesitant but kind, showing us how Kevin’s devotion to wrestling has delayed his sexual coming of age. His brothers are even younger when the masochistic demands of the sport take their toll on them with a biblical force: David dies after rupturing an intestine, Kerry loses a foot after a motorcycle accident and commits suicide, and Mike (Stanley Simons) suffers brain damage that also destroys his will to live. But even before these tragedies, Kevin is paying the price of Fritz’s emotional violence. Physically impressive though he may be, Kevin can’t help but act small. The disconnect between Efron’s hulking physique and his docility underscores the impotence of these masculine games.

Movies about fighters over the past century have tended to romanticize and extol their sport’s manly virtues (Rocky); others see the fight as a gladiatorial form of exploitation (1956’s The Harder They Fall). The Iron Claw, however, paints Kevin’s dedication to wrestling as morbid in a scene where he’s flipped on his back and slammed down upon concrete in a match against the reigning world champion. He’s meant to prove his worth to his father with this fight, but a dirty move from his opponent leaves him immobile, squirming, gasping on the floor. Against reason, Kevin slowly pulls himself back into the ring, dragging his own body like a corpse. This moment doesn’t ring with the same awestruck inspirationalism of other fight-movie resurrections — think Russell Crowe in Cinderella Man, whose return to the ring after a crippling injury sends him into early retirement is cast as triumphant. Even The Fighter, another film about a toxic family mismanaging a rookie’s career, ends on a congratulatory note. Kevin’s efforts are devastating, and they anticipate the bodily sacrifices of the younger Von Erichs, whose deaths remain offscreen.

Efron’s distinct virtues as an actor correspond beautifully to the dynamics of a wrestling drama, with the sport’s exaggerated forms of masculinity laid bare by the performer’s latent idealism and soft, childlike manner. These same qualities shape the film’s sense of hurt as well — we see Kevin, his eyes frozen in shock as he curls up in a fetal position, paralyzed by the loss of his brothers. Yet with this innocence, so effortlessly conveyed by Efron, comes hope. In part healed by the creation of his own family, Kevin bats away his demons by surrendering himself to his children and their childhood, allowing himself — in a tearful moment of introspection — to display vulnerability, which was denied him in his youth. Efron communicates a sense of history not because he looks wizened and weathered but rather because we still see the boy inside.

More on The Iron Claw

- The 50 Greatest Sports Movies of All Time

- Vulture’s 2024 Summer Pop-Culture Gift Guide

- Everything The Iron Claw Leaves Out About the Von Erich ‘Curse’