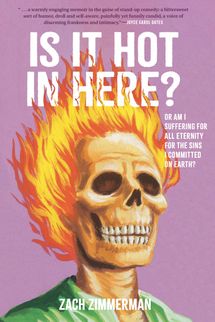

If Southern Baptists have any maxim they like to pretend to live by, it’s “Love the sinner, hate the sin.” Some use it as a semantic excuse for prejudice; many don’t even bother to fake it anymore. New York–based comedian Zach Zimmerman was raised on this particular brand of American Evangelicalism and picks it apart in smart, deeply personal comedy, so let this fitting piece of Bible Belt wisdom inform your reading of this excerpt: Love the sinner Zach Zimmerman, hate the sin of how long it took Zach to get into RuPaul’s Drag Race. In a debut collection of essays, Is It Hot in Here (Or Am I Suffering for All Eternity for the Sins I Committed on Earth)?, out April 18, the comedian explores religious guilt, carnivorous family members, queer community, and Red Lobster. Here, Zimmerman preaches on hookups, identity, and Alyssa Edwards.

1.

In a dressing room, a shy college first-year tried on a black bra, a black dress, and a red wig. The Walmart attendant looked on in dismay. A few hours later, they entered a college drag competition with too little clothing and too much Everclear. You’re never fully dressed without a shot. Inebriated and uninhibited, they took to the runway. They danced in the sacred way known only to a nineteen-year-old Southern Baptist whose body knows its queerness before the mind does. A nipple reveal in the final round clinched the title. I won.

2.

I watched my first episode of RuPaul’s Drag Race for the same reason anyone does anything they don’t want to do: a very cute boy. I had just moved to New York, where drag — and my dodging of it — seemed to matter more. During my first year of college, when my only out gay friend, Jacob, invited me to watch the premiere, I said no. A chance choice gave way to inertia; unchecked inertia became identity. But when the aforementioned Very Cute Boy asked me where I’d be watching the Season 10 premiere, I named the only gay bar I could think of.

Therapy was a Hell’s Kitchen gay bar where I once went home with a man who controlled his apartment lighting with his watch. I learned this fun fact when he woke me up at 3 a.m. to kick me out. Therapy is also where I arrived on a cold Thursday night to make good on my claim to the Very Cute Boy.

I quickly learned there’d be no talking during the feature presentation. Chitchat was self-policed by a hundred people trying to hear the show projected onto a small screen. During commercial breaks, the TV audio feed, much to the dismay of advertisers across America, was replaced with a local drag queen’s commentary. I couldn’t keep up with her references.

On my first date with the Very Cute Boy that weekend, we saw the gay high school rom-com Love, Simon. I oversympathized with the villain, who was a high school mascot like I had been. I also made a point of mentioning that I’d seen an episode of Mama Ru’s program.

“You’ve only seen one episode?” he asked.

It turns out that only brushing your teeth the night before a dentist visit is not an effective oral hygiene regimen.

There was no second date.

3.

Alyssa Edwards, a contestant on the fifth season of Drag Race, quickly became a fan favorite. The smooth southern talker and trained dancer had a penchant for non sequiturs and a signature “tongue pop.” She didn’t win the competition, but she won the war: a return to an All Stars season and a spin-off Netflix series about her dance studio in Texas.

I learned all this in the twenty-four hours before opening for her. In a Google haze, I mined my material for broad appeal gay jokes, penned new drag jokes, and furiously texted my Drag Race fan friends for a download on who she was.

I arrived at the venue a half hour before the first show. The cavernous, underground three-hundred-seat theater just off Broadway in Times Square hosted headliners. Tonight would be Alyssa’s stand-up debut. Would she make a reference I wouldn’t get? Should I lie and say I’m a lifelong fan? I was terrified I was going to be fired but also convinced we were going to become best friends.

I walked through the kitchen, feeling at home with the servers, before knocking on the closed dressing room door. A beautiful southern belle (from the waist up) greeted me.

“Hi, I’m Zach, your opener.”

“Oh, hi, Zach.” Alyssa was mid–costume change. We stood in awkward silence.

“Is there anything you want me to say?” I asked.

“You can say you’ve seen Alyssa’s Secret, and now it’s time to see Alyssa.”

“Alyssa’s what?”

“Secret. My web series.”

My research had not covered the web series.

“Of course. Yes.”

I said thank you and closed the door. I wasn’t sure if I’d been made.

The venue started to fill up with gay men, straight women, and their very supportive husbands. I started to worry I’d be outed as a Drag Race denier introducing a god I didn’t worship.

I took the stage, did my set, and said Alyssa’s name a lot (the trick to opening for anyone). Your main job when opening for someone is to not be that someone, and I was very good at not being Alyssa Edwards. When my ten minutes ended, I introduced a video. When her prerecorded voice gave way to her live one, the audience responded in a way I’ll be jealous of until the day I die.

“Hello, Caroline’s!”

Alyssa appeared from backstage in high blond hair and a long fur robe. The audience sprang to their feet and clapped and hollered. The slower she walked, the wilder they became.

“I thought I was on Broadway. They got me in a diner!” she joked. The audience died.

I stood in the back corner with the bouncer, having lost my seat to a paying customer, and understood nothing Alyssa said for an hour. All I understood was that she was killing. I witnessed the rapture of gay religion, the lightness where we all seem to become one just above our heads, but I was an outsider to her cult.

Before the final show, Alyssa’s assistant came over to me.

“Alyssa wants you to wear this.” He handed me a blue 8-foot boa.

The blue, queer snake around my neck resurrected my knowledge of good and evil. I took the stage with a new, queer energy, my hips unlocked, my arms freed from my sides.

“When Alyssa Edwards asks you to wear a boa, you wear the boa,” I told the audience. They applauded in agreement.

After the show, I snuck back to the dressing room.

“Where we going out tonight?!”

“Oh, baby, I got a 6 a.m. flight. I have a dance class to teach tomorrow.”

I went and bought a round of shots and snuck back into the dressing room. Alyssa’s things were being thrown into suitcases by two assistants.

“Shots! Shots! Shots!”

“Oh, I don’t drink, baby.”

“Oh.”

An assistant felt bad and did one of the shots with me.

“How do you come down after a show like this?” I asked.

“Oh, I take a long bath. I’ve got this down to a science.”

I started to leave and saw the assistant to the booker. I was tipsy enough to ask, “How did I get this gig exactly?”

“We wanted someone gay,” she said, “not too fabulous.”

4.

All year, a friend had hyped an upcoming drag fest to me as an accepting, queer utopia. I bought my ticket and saved the date.

Unsure what to wear, I donned a black mesh tank and a haphazard collection of ropes (“Random rope play is not safe,” a festivalgoer reprimanded me) and put some of my friend’s makeup on (“You look like that meme of the young girl with bad eye shadow and bad lipstick,” a friend pointed out).

At the festival, drag divas and pop princesses served gender-bends and death drops, constructions and destructions, presentations and provocations, with tucks and twists and boobs and butt pads and smoky eyes — all for wrinkled dollar bills and the screams of their people.

After a few numbers and enough Vodka Red Bulls to feel like college, I heard the audience erupt in a familiar way. Nina West, recently baptized into RuPaul’s TV empire, took the stage. The festival was mostly edgy local queens, but no one is immune to celebrity. Nina performed a Disney medley with clips from The Lion King, The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, and double Mulan, paired with quick-change outfits from each princess. Recognizable chords and color patterns awoke a secular chorus of queers in the Queens warehouse. We had sung these songs in the carpeted living rooms of the ’90s when Love, Simon, Drag, and Race were just nouns. Old was reborn through lip sync and the sacred recitation of secular Bible verses, fringe gospels that forged a new queer canon and community. Culture bound us together so we could lose ourselves for a moment, the queen a lightning rod to help us connect with the clouds.

I was also pretty drunk.

So I started crying.

I cried at the coming together of people who were left out. I cried for the nostalgia I missed out on because of the culture I’d banished. It must be what Jacob and the Very Cute Boy feel when they watch Drag Race, what the crowds felt for Alyssa, what the room was feeling for Nina, what I had felt but forgotten as a first-year. I cried because when you grow up feeling on the fringe, it’s easy to reject an invitation to come inside.

New nostalgia washed over me like applause, like community, like sweat at the college drag ball when things were ever clear.

Editor’s note: Zach has now seen almost every episode of Drag Race and wants Alyssa Edwards to know she’s drop-dead gorgeous.

Excerpted from Is It Hot in Here (Or Am I Suffering for All Eternity for the Sins I Committed on Earth)? by Zach Zimmerman, published by Chronicle Books.