In 2013, playwright David Adjmi came up with the idea for Stereophonic, a show about a group of ego-clashing, Fleetwood Mac–esque musicians working on their soon-to-be-epochal rock album in the mid-’70s. The play would need music — mostly bits and pieces of it as the band struggles to finish their own Rumours. A friend had suggested Adjmi reach out to Will Butler. He joined the project the following year.

At the time, Butler was still a multi-instrumentalist in Arcade Fire (he left the group in 2021). He had never worked in theater before but was drawn to the concept. He knew what it was like to be in a band, struggling to put out a single good song and striving to find collective inspiration that didn’t compromise his own creativity.

Eleven years later, Stereophonic is making its Broadway debut in April. In the fall, it received rapturous reviews during its Off Broadway run (it was one of our picks for best play of 2023) with special praise reserved for Butler’s songwriting. The music in Stereophonic challenges the audience to both sympathize with and loathe each of the five band members — guitarist and vocalist Peter, bassist Reg, vocalist Diana, keyboardist and vocalist Holly, and drummer Simon — most of whom are entangled in thorny romantic relationships with one another. This tension comes to a head with “Masquerade,” a groovy stomper of a tune that the band agonizes over. It’s the only full song heard in the play. First, the tempo is too slow. Then it’s too muddy. The drummer nearly walks out in a rage because he can’t nail the beat without the help of a click track. They finally nail it on take No. 37 — a rare moment of euphoria in a studio plagued by deception, jealousy, and cocaine. The song is confirmation to the audience that the band indeed has the talent.

So how does somebody create a fake classic-rock song that actually sounds good?

1.

Give It a Timeless Sound

I wanted “Masquerade” to feel transcendent. Other pieces of music do that in the play, but “Masquerade” is one of those where you feel why they’re doing what they’re doing. Why are we showing the audience this song front to finish? It had to be really bold and really fun. I wanted it to feel both like 1976 and the fact that 1977 is coming. I wanted it to be rooted in the time, but also I wanted to see Kurt Cobain listening to it in 1989; I wanted to see a 16-year-old me listening to it in 1998. I wanted it to have that timeless character, like, Oh, this feels like an era like “Stayin’ Alive,” but it also feels like it could be today.

2.

Root It in the Text

Most of the music is reverse engineered from the script. It’s like, So Holly went to the David Bowie show and Sylvester opened in 1972 and then she probably had dinner at fucking Eric Clapton’s house at some point and he played her these two reggae records. These are people that listened to the White Album. The British people in the band were probably friends with people that were in the first draft of the Rolling Stones. They were playing ’50s American blues music. Holly’s parents definitely had Glenn Gould’s Bach: The Goldberg Variations on their shelf. It’s not like, Oh, let’s see the albums that came out in 1975 and let’s try to copy that. I was trying to root it in where they came from. This type of writing isn’t strange to me — every band I’ve ever been in has written in character at times. It’s either straight up a persona you adopt or you’re writing a story. It’s like “Nebraska,” by Springsteen, where you’re like, I’m a serial killer. You’re putting on hats.

3.

Find the Right Riff

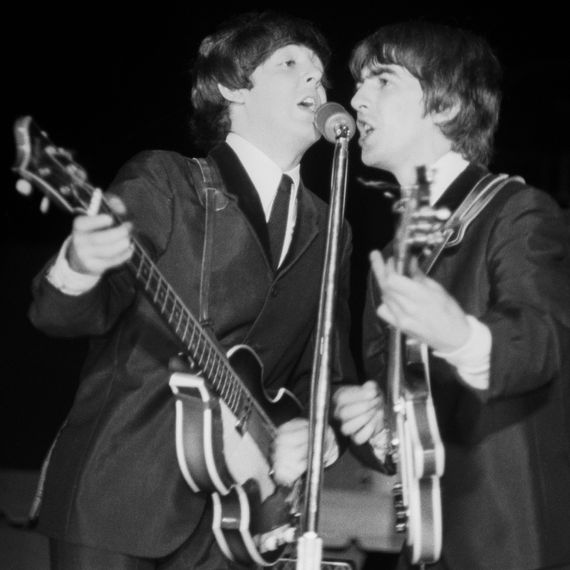

One technical constraint on this song is that it had to be a riff. It had to have an element of comedy — you’re hearing it so many times and it feels like your eyeballs are going to fall out. It was tricky to do. On a very basic level, it’s rooted in Peter because Peter’s a guitar player. This guitar riff was something in his head that he couldn’t stop. It’s in his fingers and in his brain, going over and over. That’s what happened here, too. Some riffs of the era were inspiring. It’s a little bit “Helter Skelter” from the White Album and “I Want You (She’s So Heavy)” from Abbey Road, the late Beatles. “Masquerade” is kind of like Stevie Wonder playing a country song.

4.

Pair It With Some Brooding Lyrics

Lyrically, it’s a medieval journey song. It starts with “Got my ticket to the masquerade,” which is kind of like bayou rock. It’s like going on a pilgrimage to something you know is hollow, but that’s the only place to be. You start there and then realize how lonely you are: I’m going to the party, and I’m so lonely. Fuck, I guess I’m going to go to the bayou. Wow. Life is dark out here, huh? There’s a fear and an angry undercurrent in there. The outro, “I’ll see you when I get there,” is really dark. You know when the Police sang, “Every breath you take / I’ll be watching you”? That seems so romantic, but you’re like, Huh. I guess the music made it that way, but that’s dark. It’s a journey to hell — I’ll see you in hell. But it’s also fun. It’s about a party.

5.

Do It Live

It only clicked into place when we heard the cast sing it. The second we had those three singers — Tom Pecinka, Sarah Pidgeon, and Juliana Canfield — it was like, Oh, okay, this is a band. Hearing the three of them sing together does a lot of dramatic work, where you’re just like, Shit, they sound good. They’re meant for this. There’s a version of a song that’s just Peter and Diana singing, and there’s a version that could just be Peter singing. They’re such good singers with characteristic voices that it blends so well. It makes it work on every level.

6.

Throw It All Away

Sometimes, in a band, you make something really awesome but it’s just missing something. Or your brain can’t comprehend that it’s awesome, you cut it, and it gets destroyed. Either way, it’s not on the record. It made sense that they would record something so great and then be like, “Oh, but we already have a rocker on the record and it’s better than this one.” I could see how everyone would love it and then they would start to lose their minds.

MORE FROM THIS THEATER SEASON

- Made for Jessica Lange

- The Weird, Wide-Eyed, Weepy, and Wild Voices on Broadway

- Amy Herzog and Sam Gold Are Just a Couple of Ibsen Lovers