Maya, a 21-year-old woman living in New York City, chuckles that she was “still very much in utero” when HBO’s The Sopranos premiered in early 1999. After watching (and rewatching) the series between her senior year of high school and freshman year at college, she started a Twitter page — sopranos out of context — to share screenshots from the show. Earlier this year, the account had around 3,000 followers. Now over 100,000 people follow the account to see snaps of Artie Bucco with a towel on his head and Christopher wondering how Lou Gehrig got Lou Gehrig’s disease.

The account’s popularity coincides with a resurgence of Sopranos pop culture over the course of the year. The wave isn’t being propelled by longtime fans, but by Zoomers just discovering the show, in all its existential dread and outlandish humor. Maya and other Gen-Z folks aren’t just watching the show for a mafia drama fix. When Tony shrugs and asks “Is this all there is?” it hits different for a generation riding out the miserable, dying gasps of American capitalism, imperialism, and white supremacy while climate crises dismantle the country faster than any revolution could. Add in a pandemic? Madone.

Maya says she and other Zoomers reviving the series are reimagining its position in pop culture too. The president is in hospital and Mike Pence is waiting in the wings? There’s a Sopranos scene for that. Big Pussy Bonpensiero going in the water? WAP. “It’s like we’re speaking about the show in our own language,” says Maya, via memes and pop-culture minutiae that often convey a more acute evisceration of their conditions than an academic paper could.

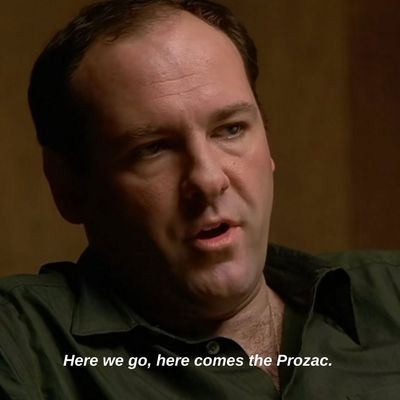

Other Zoomer fans concur. Lexi, a 22-year-old fan based in Southern California, credits her generation’s experiences and understanding of mental illness and therapy as critical pretexts for their engagement with the show. “The way Tony talks about feeling like shit and his unhappiness with his life and the way it’s going is a commonality among many of my friends and peers,” she says. Leila, a 22-year-old fan from Brooklyn, originally registered The Sopranos as “the show with the big guy in the chair” while their dad watched it. After rewatching it, they describe it as a “documentation of the white American hypermasculine mentality, but it also shows the repercussions [that] has on everyone around them.” Leila says their fixation on the show was a running joke in their friend group until their friends found themselves bingeing it, too. “It’s such a fun and chaotic show,” they say.

Those twin assessments hit on two fundamentally different experiences of the show for Gen Z: the cursory one of The Sopranos as a comedic entertainment object, and the intellectual one, where the series is filtered through a 2020 lens that’s armed with abolitionist theory, anti-capitalist vigor, and climate nihilism. It means adoring the hilarious phenomenon of Tony huffing and squinting at A.J.’s shaved eyebrows while reading subtexts of imperialism, colonialism, and white supremacy.

Pandemic conditions have only boosted the show’s relevance. In Philadelphia, 22-year-old Simon says that The Sopranos was perfect quarantine material. “Suddenly, you had all this alone time, and watching hours of James Gandolfini act through anxiety and the dullness of life so well, it’s just good company through all of this,” he says. “Like listening to sad music when going through a breakup.”

“The show absolutely speaks to our conditions,” says Benji, a 17-year-old Twitch streamer based in New Jersey. Like Tony, Benji feels he’s living at the end of an era. “I often find myself thinking that I’ve come too late for anything good,” he says. Benji identifies with A.J.’s existential nihilism, but also connects with the nuances of other characters’ struggles: “It kind of reminds me of the worst of myself and the best of myself, and the world.”

Elisa Hernández Pérez, an Iowa-based Ph.D. in media and communications studies who co-authored a 2016 paper on The Sopranos, Mad Men, and American capitalism, says that this year’s Zoomer-led memeification of The Sopranos is a natural progression of cultural interpretation. Hernández Pérez says that while initial readings of the show centered Tony’s disenfranchisement, newer analyses position it almost as parody: Rather than hearing Tony’s woes and relating, a younger generation of viewers can hear them and chuckle at another middle-aged white man victimized by the systems he’s supporting, incapable of imagining an alternative.

“I think it’s fascinating that now people are reading it from humor, because you can go one step further and read it as parody,” says Hernández Pérez. She says that like Tony, older viewers may have felt let down by the American Dream, while younger ones scoff at the concept altogether. “The next step is making fun of the fact that that frustration even exists. ‘How could you even believe this?’”

Hernández Pérez says that shows like The Wire and The Sopranos also draw attention to the evergreen moral relativism that typifies America’s arbitrary legal systems, which overcriminalize and imprison poor racialized communities while wealthy white criminals skirt accountability. Lexi hits upon this, too, noting The Sopranos’ juxtaposition of poor Black “criminals” against the ostensibly less threatening white gangsters.

“Why is [drug dealing] so much worse than what a company like Amazon does with the way they treat their workers?” poses Hernández Pérez. “It makes you realize how brutal all of it is.”

This year’s Sopranos memes, she continues, are an example of Gen Z’s evolution of culture critique. While academics host conventions to parse the subtexts of The Sopranos, Zoomers just make a meme that says it all. “It’s like that tweet with the guy who was like, ‘I worked on this story for a year and he just tweeted it out,’” she laughs. “It’s the exact same thing. I worked on this for years, and these kids are just tweeting it out. They’re just using different terms for it.”

“I think part of why it’s really resonating right now is because Chase was right,” says Alan Sepinwall, Rolling Stone’s chief television critic and co-author of The Sopranos Sessions, a retrospective book with creator David Chase and New York Magazine critic Matt Zoller Seitz. The show’s pilot episode affirms the experience of Benji, the Twitch streamer: “The first episode, Tony tells Dr. Melfi, ‘I came in at the end. This thing I’m involved in is over,’” Sepinwall points out. “If you’ve been living in America for the last 20 years, and especially for the last four, it really feels like something is coming to an end, that things are bad, that all of our worst impulses have grown unchecked and there’s no way of fixing things.”

“There’s a sense of loss to the show; there’s a sense of loss to Tony as a character,” continues Sepinwall. “You can relate to this idea that he feels his life should be something other and something more than what it turned out to be.”

When Sepinwall says that “the mafia is just kind of pure unbridled capitalism,” and that they’ll “bleed you for everything you are worth and they don’t care,” it’s plain and even popular to read “the mafia” as the United States. This is painfully true during a pandemic that has killed more than 300,000 Americans. And for Zoomers, it’s increasingly easy to see the Soprano family as a caricature of a country refusing to embrace its own health and well-being over money, of what Sepinwall describes as a “desperation to keep this machine churning no matter what, rather than stepping back and reexamining, ‘Hey, wait a minute, is what we’re doing here a good idea?’”

Culture critic and Death Panel co-host Beatrice Adler-Bolton, who is 30, thinks that Gen Z’s experience of The Sopranos has likely been informed by watching Adler-Bolton’s millennial cohort — a generation heralded as disrupters but still restrained by American exceptionalism and individualism — suffer and break under the weight of this sort of neoliberalism and the gig economy. “I think it’s an incredibly powerful thing, how much neoliberalism has fucked over millennials, because it’s made our generation a very good example, and it’s made us very angry,” says Adler-Bolton. “For people 10 to 15 years younger, with the pandemic now as it is, why the fuck do we even have a government? Why do we even have America?”

Or, in Gen Z parlance, America is just an enfeebled Artie Bucco, shouting that it’s the world’s leader in data collection. There’s a Sopranos meme for everything, from bodega discourse to Shakespearean tragedy. Maya has grown sopranos out of context into a digital Satriale’s, where she and other Zoomers can gather and hype up the new Megan Thee Stallion release or work through a post-post-secondary existential crisis. The Sopranos has given Gen Z a new way to connect and make collective sense of their conditions.

“We kind of see each other, you know?” Maya says.