Since the Sundance opening of James Franco’s take on Allen Ginsberg in Howl, I’d heard the movie was howlingly bad — which makes me think that some of the best critical minds of my generation have been destroyed by cynicism. The film, directed by Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman, is an exhilarating tribute from one form (cinema) to another (poetry).

It takes Ginsberg’s momentous, paradigm-changing poem as its launching pad and landing place; its beginning, middle, and end. You could call it a deconstruction except that sounds too formal. It’s a celebration, an analysis, a critical essay, an ode. Howl leaps among four distinct periods and gestures toward others. First, there is that night in 1955 at San Francisco’s Six Gallery (the event was advertised as 6 Poets at 6 Gallery) when Ginsberg (Franco) electrified a semi-intoxicated crowd with the first public performance of the poem. (You could hardly call it just a “reading.”) Second, there is Ginsberg giving an interview (the interviewer is unseen, only the turning reel-to-reel recorder) in which the now-bearded poet recounts the events leading up to that poem. Then there is the obscenity trial (dramatized from actual transcripts) of City Lights owner-publisher Laurence Ferlinghetti, who is prosecuted by David Strathairn and defended by Jon Hamm before Judge Bob Balaban. Finally, there are flights of animated angels — or, really, angels looking like sperm with comet tails who soar above a burnished urban inferno, a place of Moloch the fascist devil and fearful denizens chased by the demons of the military-industrial-government complex.

The result brings out everything that fed into “Howl,” how it changed the culture in its first years of publication, and most important, the immediacy of the poem itself, which emerges from Franco’s incantation as the work of a Whitmanesque bard, a Blakean mystic, a jazz musician, a rabbi chanting to a crowd of davening worshipers. One complaint about the film has been that the animation is too literal-minded. Perhaps it is, but it’s also rhapsodically beautiful, dissolving the boundaries between objects the way Ginserg’s words dissolved the boundaries between the physical and metaphysical. Even a much-derided image, of typewriter keys bursting into flames, has a musical truth — and I love the way manual typewriter keys are fetishized.

The trial in Howl is a handy distillation of why artists need room to break rules and shock prevailing sensibilities — Strathairn, while in no way driving the comparison home, wonderfully invokes Jimmy Stewart’s fumbling homespun wisdom act, his words in this case embodying all that is lazily reflexive in the posture. And the amusement and near incredulity in Hamm’s eyes as he hears the arguments against shocking the bourgeoisie (from Strathairn and a fatted, smug Jeff Daniels) are a true howl.

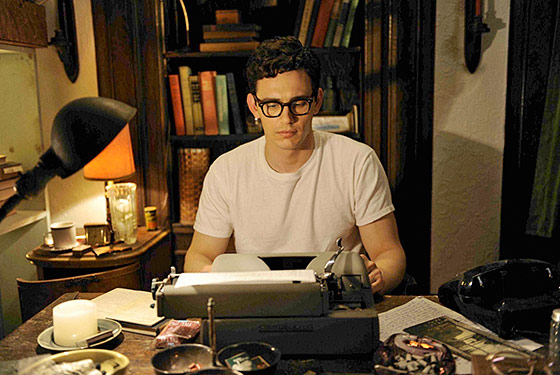

His cheeks rounded, his Jewishness conveyed as much from his grasping at his own elusive insights as his New York cadences, Franco is the movie’s perfect center. This wasn’t yet Ginsberg the teddy bear (with the ever-ready hand to pat some young man’s knee) that I and many others met on university campuses and in the Village decades later. It is the Ginsberg still assembling the pieces of his persona — as gay man, as beatnik, as political dissident, as brokenhearted mama’s boy, as paranoic who was nonetheless a fount of healthy, compassionate ecstasy.

Yes, the film can be literal-minded, yes it occasionally clunks, but Howl is truly a trip back in time — and a reminder of how much we’ve lost with the messianic Poet (by which I mean the role, not the man) now marginalized.