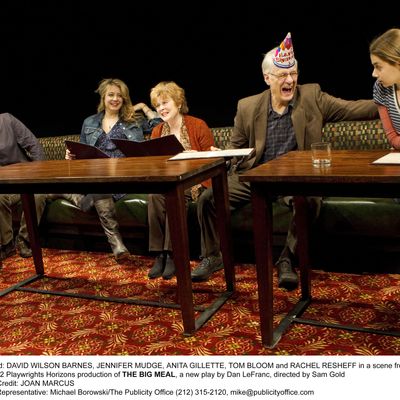

The Big Meal (at Playwrights Horizons’ Peter Jay Sharp Theater through April 8)

At last count, there were at least three Last Suppers currently onstage in midtown Manhattan. One is set to power chords and rock falsetto, one to folk twanglings, and the last, best, and least liturgical is sculpted entirely out of fraught dinner conversation and those unanswerable silences that hang, shroudlike, in the interstices. (Surprise, surprise: The director is the atmosphere craftsman Sam Gold.) In Dan LeFranc’s The Big Meal, five generations of a family (played in musical-chairs rotation by eight excellent actors, age 11 to seventysomething) are glimpsed, throughout the decades, in a spectrally generic Restaurant: First passes are made, first dates are had, births are celebrated, deaths mourned, and Eternity arrives with a side of fries. (Thrift, thrift: The funeral baked meats furnish forth the marriage table, and that’s just the appetizer course.) The inspired pairing of undersung greats David Wilson Barnes (Becky Shaw) and Jennifer Mudge (Reckless) — two of the theater world’s most convincing “grown-ups” — anchors the show emotionally. (They handle all the early-middle-aged roles, the very appealing duo of Phoebe Strole and Cameron Scoggins take the younguns’, and veterans Anita Gillette and Tom Bloom hilariously and devastatingly embody the seventh stage of man). Gold keeps LeFranc’s elegant and deft but slightly monotone stage conceit steaming along past its expiration date. The play has its limitations, and the finale is a long tail of writerly tone-poesy, but through it all, LeFranc sustains a voice and a vision — relaxed, humane, terrified, bemused — and Gold and his ensemble are just the team to array it all on the plate to best advantage. The service is excellent, and the wait isn’t as long as you think. Terrifyingly brief, in fact.

No Place to Go (at Joe’s Pub at the Public Theater through April 8)

The hangdog crooner Ethan Lipton — a working artist who, until recently, supplemented his art with a “permalance” day job he loved and had come to depend upon, financially and even spiritually — presents a lounge-y song cycle about the loss of his employment. With a few poetic exaggerations: There’s a sentient sandwich in the conference room, and the company is, in his retelling, moving itself “to Mars,” for the cheap real estate. But current employees are invited to relocate! No Place is a tuneful, modestly outraged telling of corporate betrayal, warbled by Lipton in his hot-asphalt blues growl and backed by his Orchestra, a brilliant trio made up of bassist Ian Riggs, guitarist Eben Levy, and sax-man Vito Dieterle. It’s the middle-aged satellite-radio background hum accompanying the shouts and chants of the Occupy crowd, but it’s no less incensed, if you’re listening. And listen you should, if you’ve ever had a job, lost a job, or lost a job you didn’t know you cared about until it was gone. Lipton is eulogizing the end of an epoch in the life of Creative New York: The unofficial private-sector safety net that once sustained a generation of dreamers and artists has been effectively shredded, and probably isn’t coming back. So pour yourself a tall, cold “$200 drink” (as Lipton assesses the quaffage at Joe’s Pub) and listen to the man send off an era in style.