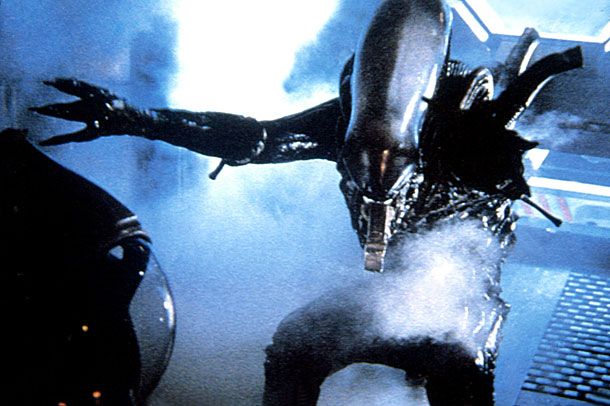

Photo: Twentieth Century Fox

Ever since the project was announced, director Ridley Scott has maintained that Prometheus, his first science-fiction film since 1982’s Blade Runner, was not a prequel to his 1979 space-horror film Alien. Having seen the film, we can report that this is most certainly false. The film, which opens today, is the latest in a fascinating franchise. Three sequels followed the first, all helmed by directors — James Cameron, David Fincher, Jean-Pierre Jeunet — who took the elements of the original and added their own memorable visual styles.

To kick off a new feature called “Vulture Scavenger,” we watched all four Alien films (repeat after us: There are no Alien v. Predator movies), listened to multiple director commentaries, watched dozens of featurettes, read books, and scoured old newspaper and magazine articles in search of the tidbits that any obsessive Alien fan would love to know.

1. The first film’s gory central set piece, in which a creature explodes out of the torso of one of the Nostromo’s crewmembers, was part of the story from the very beginning. According to Jason Zinoman’s history of seventies horror films, Shock Value, writer Dan O’Bannon suffered from Crohn’s disease, a disorder that resulted in extreme gastrointestinal pain. In the midst of writing a version of the story, he awoke one night with the idea for the chestburster, which mirrored his own suffering.

2. O’Bannon also enjoyed the idea of having a man give birth: “Having the victim in a horror film always be a woman was a cheap shot. I always imagine the director jerking off, ‘Oh, I can’t wait to see that woman get chopped to pieces.’ No, I want to see a man get it because I knew it would make the men uneasy.”

3. When it came time to shoot the film, the actors were obviously aware of what the scene involved — having read the script — but they had no idea it would be so gory. Such a large blast of fake blood blew into actress Veronica Cartwright’s face that she fell backwards over a small table and fell on her back, cowboy boots in the air.

4. In the mid-seventies, Chilean director Alejandro Jodorowsky (El Topo) was assigned to direct a film version of Frank Herbert’s Dune. The filmmaker gathered an odd contingent of creatives around him — Dan O’Bannon (who at that time was known for doing the special effects on John Carpenter’s Dark Star), Salvador Dalí (as an adviser), Jean Giraud (better known as the comics artist Moebius), and Swiss surrealist painter H.R. Giger. When Giger and O’Bannon met for the first time, in a Paris hotel, Giger was smoking opium. “For his visions.”

5. After that project fell apart, the group all scattered to the wind. But when O’Bannon’s Alien script (initially titled Star Beast) started to move forward, Giger came back on to work on designs for the creature, the derelict spaceship, the planet surface, the Space Jockey (more on that later), the chestburster, and the Alien eggs.

6. Moebius’s main contribution to the film was the bubble-helmeted surface suits, which were later given a medieval/Japanese samurai warrior flair.

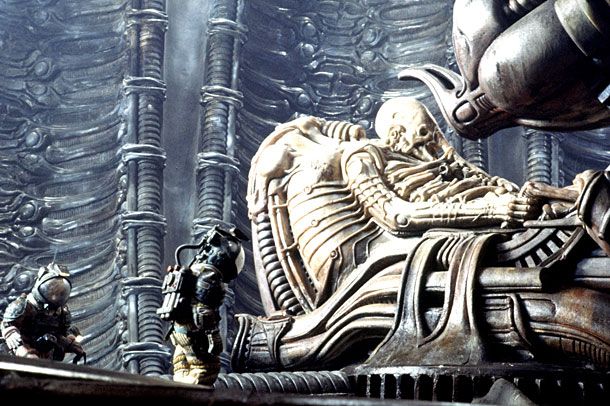

Photo: The Kobal Collection

7. Despite Ridley Scott’s initial hesitance at having the Alien be a man in a suit, the production eventually cast a six-foot-ten Nigerian-born graphic arts student named Bolaji Badejo. Discovered in a London pub, he got the job after several lithe female models (and Peter Mayhew, who played Chewbacca in Star Wars) tested for the part.

8. John Hurt was not the first actor cast as Kane. Jon Finch, who had played Macbeth in Roman Polanski’s 1971 film version, had to drop out of the role on one of the first days of shooting, on account of a bronchial attack. (Ironic? Yes.) He had already prepped for the role by having a chest and neck built for his big chestburster scene. Hurt took over the job the very next day.

9. Veronica Cartwright flew to London, where the film was shooting, convinced that she had gotten the part of Ripley. Her representatives kept insisting over and over to her that she had won the film’s lead female role. But the costume department broke the news to her — she was whiny Lambert. (Cartwright was later assured that the role was an important one, the audience surrogate, but who knows whether or not she was just told that to allay her anger at losing the Ripley role.)

Photo: ?20thCentFox/Courtesy Everett Collection

10. There were many concepts and plot points from O’Bannon’s original story and script that did not make it into Alien. They stuck in Ridley Scott’s head, and for years he has talked about returning to the characters of the Space Jockey (the name they were given during filming) to try to find out where that humanoid creature came from. In 1984, as Aliens was on the horizon, Scott said that his version of a sequel would have explored “what the Alien is and where it comes from.”

11. In fact, the Space Jockey was almost dropped from the first film entirely. The giant, biomechanical Space Jockey set, designed by Giger from an early painting of his, was an expensive proposition. But according to Ron Shusett, who co-wrote the original story with O’Bannon, Scott fought back against the studio, saying, “We need this. This is our Cecil B. Demille shot. When they see this, they know it’s not some little thing, not miniatures … Your jaw drops and you know you’re watching an A-level movie.”

12. We’d like to keep this feature spoiler-free. But we can say that the elements that got cut from the 1979 Alien that have found their way into Prometheus are a giant pyramid/temple full of dangerous items as well as a curious decapitated head.

Photo: ?20thCentFox/Courtesy Everett Collection

13. Carrie Henn had never acted before scoring the role of Newt, the last surviving colonist of LV-426, in James Cameron’s sequel. And she has never acted since. At last notice, she was a schoolteacher in California.

14. One of our favorite lines in the movie is one that has always annoyed Henn. “It’s the only line that anyone I ever run into remembers,” she says in one Aliens documentary. “And anyone who ever wants to irriate me — my friends — they just say this. They say it for everything. The line was, ‘They mostly come out at night. Mostly.’ And my friends will say, ‘Oh, we mostly go to the movies at night. Mostly’ They just come up with whatever they can possibly come up with.”

15. Cameron’s initial version was two and half hours long. Rather than trim a bunch of individual moments, he decided to just cut entire scenes. Below are some of the most prominent.

16. An early exchange between Ripley and Burke (Paul Reiser), in which he delivers information about Ripley’s daughter, who died two years prior. Weaver later expressed dismay at the excision of this scene, which she claims to have based all her character beats on, especially all the stuff about Ripley’s need to kept Newt safe.

17. An early scene set in the colony of “Hadley’s Hope” on LV-426 (dubbed Acheron by Cameron for the film, though the name is never said out loud). Newt and her brother (played by Henn’s real-life sibling) drive out with their parents to the wreck of the derelict craft from the first film. The parents disappear inside. When they emerge, Newt’s father has a facehugger attached to his head.

18. Several moments with some kickass remote-controlled sentry guns that amp up the tension right before the horde crashes through the ceiling.

19. Giger did not work on the sequel, and Cameron and visual-effects supervisor Stan Winston made several changes to the basic Alien design.

20. Winston’s Aliens had three “fingers,” as opposed to the original model’s six-finger hands.

21. “The Alien head in the first film was very smooth,” said Cameron. “Underneath, it had a skull shape and a ribbed design. Originally it was designed to see that [skull] through a kind of transparent surface in the Giger design. I thought what was underneath was more interesting.” So they removed the translucent dome altogether.

22. The film’s facehuggers had longer tails and were (obviously) more mobile than the one we see in the Scott film.

23. The Alien Queen — as memorable a creation as Giger’s initial model — was created entirely by Winston and his team. The fourteen-foot beast was a combination of a miniature, a rod puppet, a hyrdraulic head and neck, a face operated by cables, and a body supported by a crane.

24. Since there were so many Aliens in this film (as opposed to the single creature from the previous), Cameron decided not to make full suits. Instead, he and Winston had actors dress in black unitards and wear Alien-suit tops. Creative camera angles, lighting and quick cuts hid the lack of Alien bottoms.

25. The film was nominated for several Academy Awards, the most prominent being Weaver’s nod for Best Actress, the first such nod for a sci-fi or action film. (She lost to Marlee Matlin.)

26. Weaver hadn’t even been signed up for the sequel when Cameron began to write his script. Everyone just assumed that she was already onboard. When she asked for a significant payday, Fox initially told Cameron to proceed without the character of Ripley. After they finally agreed to pay her fee, Weaver was initially disturbed by the film’s militaristic tone (“It’s hard for me, morally, to justify being in a movie with so many guns … I give money to anti-gun legislation. I never even go to see movies with guns,” she said at the time), but proceeded nonetheless.

27. The third film was troubled from the beginning — it went through several writers and directors before settling on a young David Fincher, who took on the Alien sequel as his first feature film. Way before that, though, cyberpunk writer William Gibson wrote an early version of the script mostly set on a space station and featuring the return of Hicks and Bishop. At one point. Renny Harlin, who had just come off Nightmare on Elm Street 4, was attached to direct. He eventually left to do Die Hard 2.

28. The studio then approached Vincent Ward to direct. He signed on and came up with a far-out idea that involved a

planet made out of wood populated by luddite monks. (You can see many of his sketches and concepts

here.) He eventually left the project after the studio started to balk at the potential cost of his vision, despite the fact that they had already started building some sets. Also, according to producer David Giler, “No one could ever answer why [the wooden planet] was there, why it wasn’t rotting away, how it got there.”

29. The basic concept of the monks — celibate men out in the middle of nowhere — was kept, but morphed into a penal colony full of rapists and murderers. So, almost the same thing.

30. The drama did not stop once the film secured Fincher as director. He clashed constantly with the studio and the film went more than twenty days over schedule. Initially scheduled for Easter 1990 under a previous director, it was then bumped to summer 1991, then Christmas of that year, and then all the way to Memorial Day 1992. The final budget was a whopping (for that time) $50 to $60 million.

31. Fincher was given eight days of reshoots. Then, at the very last minute — mere weeks before the film was slated to finally come out — it was decided that the ending should be tweaked. “The missing ingredient turned out to be six more seconds, drawn from the original script and shot at a price estimated at $500,000,” wrote a 1992 Chicago Tribune piece.

32. Several sequences were cut from the film, including an opening that saw Ripley discovered on an oily beach, a scene where a creature bursts out of a giant ox, and an entire subplot involving the character Golic (Paul McGann) worshipping and then releasing the trapped xenomorph.

33. “It was a baptism by fire. I was very naive … I’d always had this naive idea that everybody wants to make movies as good as they can be, which is stupid. So I learned on this movie that nobody really knows, so therefore no one has to care, so it’s always going to be your fault. I’d always thought, ‘Well, surely you don’t want to have the Twentieth Century Fox logo over a shitty movie.’ And they were like, ‘Well, as long as it opens.’”

34. “They would say, ‘Look, you could have somebody piss against the wall for two hours and call it Alien 3 and it would still do 30 million dollars worth of business.’ That’s the impetus to make these movies, you can’t keep the people away.”

35. “When you direct a [music] video, people give you the money and say, ‘Call us when you’re done.’ Movies aren’t like that. I think you’re always in over your head on your first movies, even if it’s a very small movie. All you can do is lick your wounds when it’s over.”

36. “I have many, many friends who are vice-presidents and presidents of production at movie studios and they never understand this very simple thing: My name’s going to be on it. Your name’s not on it. Your point of view is as valid as any member of the audience. But it’s a different thing when you’re name’s on it, when you have to wear it for the rest o your life, when it’s on a DVD and it’s hung around your fucking neck. It’s your albatross.”

Photo: ?20thCentFox/Courtesy Everett Collection

37. Weaver was not particularly excited to go back for a third film, especially not one whose preproduction had dragged on for so long. But, she successfully lobbied for a bigger payday and made sure that the movie contained no guns.

38. According to a 1992 Chicago Tribune article, “The question of salary, however, is no joke to Weaver. Although she feels that ‘it’s in bad taste to talk about how much one is paid,’ she makes it clear that she found her payment for the last two Alien films rather distasteful. ‘I got paid not very much for the first two,’ she says, noting that 70 percent of her $1 million fee for Aliens got eaten up by American and British taxes and the agent’s fee.”

39. In order to keep her head sleek, Weaver shaved her head three times a week while shooting. When they had to reshoot the film’s ending, an expensive bald cap was required to mimic the look.

40. Though Whedon is credited as the film’s sole writer, he has been very vocal about how everyone else ruined his script. “It wasn’t a question of doing everything differently, although they changed the ending; it was mostly a matter of doing everything wrong. They said the lines … mostly … but they said them all wrong. And they cast it wrong. And they designed it wrong. And they scored it wrong. They did everything wrong that they could possibly do. There’s actually a fascinating lesson in filmmaking, because everything that they did reflects back to the script or looks like something from the script, and people assume that, if I hated it, then they’d changed the script … but it wasn’t so much that they’d changed the script; it’s just that they executed it in such a ghastly fashion as to render it almost unwatchable.”

41. One early Whedon version ditched Ripley altogether; and one saw an adult cloned Newt as one of the protagonists.

42. The biggest difference between Whedon’s script and the final film was the ending, which was rewritten during shooting to save money. The writer had originally included a climax that took place on Earth, with Ripley, Call (Winona Ryder), and others fighting the newborn on the surface. According to the Alien Anthology, “Whedon wrote five different possible endings set on Earth. Whedon’s endings ranged in location from a forest, a junkyard, a maternity ward and a desert. The studio even considered crashing [spaceship] the Betty into the Eiffel Tower.”

43. The much-maligned Newborn Alien would have been more roundly mocked had an original design element been left in. Director Jean-Pierre Jeunet had a mixture of male and female genitalia located on the bottom front half of the creature. (You can

see it here.) Naturally, the studio asked for it to be removed, and so the naughty bits were digtially scrubbed out.

44. It speaks to the wrongness of Alien: Resurrection that Ripley’s over-the-shoulder, nothing-but-net basketball shot is one of the film’s more memorable moments. It was a real shot, no tricks involved. Weaver trained for two weeks and scored the basket on the scene’s sixth take. The cast and crew exploded in cheers, and actor Ron Perlman broke character, requiring Jeunet to cut the scene a little earlier than he planned.

![19. Giger did not work on the sequel, and Cameron and visual-effects supervisor Stan Winston made several changes to the basic Alien design.

20. Winston's Aliens had three "fingers," as opposed to the original model's six-finger hands.

21. "The Alien head in the first film was very smooth," said Cameron. "Underneath, it had a skull shape and a ribbed design. Originally it was designed to see that [skull] through a kind of transparent surface in the Giger design. I thought what was underneath was more interesting." So they removed the translucent dome altogether.

22. The film's facehuggers had longer tails and were (obviously) more mobile than the one we see in the Scott film.

23. The Alien Queen — as memorable a creation as Giger's initial model — was created entirely by Winston and his team. The fourteen-foot beast was a combination of a miniature, a rod puppet, a hyrdraulic head and neck, a face operated by cables, and a body supported by a crane.

24. Since there were so many Aliens in this film (as opposed to the single creature from the previous), Cameron decided not to make full suits. Instead, he and Winston had actors dress in black unitards and wear Alien-suit tops. Creative camera angles, lighting and quick cuts hid the lack of Alien bottoms.](https://pyxis.nymag.com/v1/imgs/9e2/9a2/44a1966ddbdccbe73b37d8fce92e5aceb2-07-aliens-queen.rhorizontal.w700.jpg)

![27. The third film was troubled from the beginning — it went through several writers and directors before settling on a young David Fincher, who took on the Alien sequel as his first feature film. Way before that, though, cyberpunk writer William Gibson wrote an early version of the script mostly set on a space station and featuring the return of Hicks and Bishop. At one point. Renny Harlin, who had just come off Nightmare on Elm Street 4, was attached to direct. He eventually left to do Die Hard 2.

28. The studio then approached Vincent Ward to direct. He signed on and came up with a far-out idea that involved a planet made out of wood populated by luddite monks. (You can see many of his sketches and concepts here.) He eventually left the project after the studio started to balk at the potential cost of his vision, despite the fact that they had already started building some sets. Also, according to producer David Giler, "No one could ever answer why [the wooden planet] was there, why it wasn't rotting away, how it got there."

29. The basic concept of the monks — celibate men out in the middle of nowhere — was kept, but morphed into a penal colony full of rapists and murderers. So, almost the same thing.](https://pyxis.nymag.com/v1/imgs/2dc/21d/8d42084fda94509bf3e254d04c18e0a9c6-09-alien-3-monks.rhorizontal.w700.jpg)

![33. "It was a baptism by fire. I was very naive ... I'd always had this naive idea that everybody wants to make movies as good as they can be, which is stupid. So I learned on this movie that nobody really knows, so therefore no one has to care, so it's always going to be your fault. I'd always thought, 'Well, surely you don't want to have the Twentieth Century Fox logo over a shitty movie.' And they were like, 'Well, as long as it opens.'"

34. "They would say, 'Look, you could have somebody piss against the wall for two hours and call it Alien 3 and it would still do 30 million dollars worth of business.' That's the impetus to make these movies, you can't keep the people away."

35. "When you direct a [music] video, people give you the money and say, 'Call us when you're done.' Movies aren't like that. I think you're always in over your head on your first movies, even if it's a very small movie. All you can do is lick your wounds when it's over."

36. "I have many, many friends who are vice-presidents and presidents of production at movie studios and they never understand this very simple thing: My name's going to be on it. Your name's not on it. Your point of view is as valid as any member of the audience. But it's a different thing when you're name's on it, when you have to wear it for the rest o your life, when it's on a DVD and it's hung around your fucking neck. It's your albatross."](https://pyxis.nymag.com/v1/imgs/797/d1d/ad0c79cf08370584391dcc8a9bfc8c2634-11-alien-3-david-fincher.rhorizontal.w700.jpg)

![40. Though Whedon is credited as the film's sole writer, he has been very vocal about how everyone else ruined his script. "It wasn't a question of doing everything differently, although they changed the ending; it was mostly a matter of doing everything wrong. They said the lines ... mostly ... but they said them all wrong. And they cast it wrong. And they designed it wrong. And they scored it wrong. They did everything wrong that they could possibly do. There's actually a fascinating lesson in filmmaking, because everything that they did reflects back to the script or looks like something from the script, and people assume that, if I hated it, then they'd changed the script ... but it wasn't so much that they'd changed the script; it's just that they executed it in such a ghastly fashion as to render it almost unwatchable."

41. One early Whedon version ditched Ripley altogether; and one saw an adult cloned Newt as one of the protagonists.

42. The biggest difference between Whedon's script and the final film was the ending, which was rewritten during shooting to save money. The writer had originally included a climax that took place on Earth, with Ripley, Call (Winona Ryder), and others fighting the newborn on the surface. According to the Alien Anthology, "Whedon wrote five different possible endings set on Earth. Whedon's endings ranged in location from a forest, a junkyard, a maternity ward and a desert. The studio even considered crashing [spaceship] the Betty into the Eiffel Tower."](https://pyxis.nymag.com/v1/imgs/432/719/52a6d6fa90649d228551f4a782f5bf5f72-13-alien-resurrection-joss-whedon.rhorizontal.w700.jpg)