Writer-director David Mamet’s HBO movie Phil Spector is a curious creature. It makes a big deal out of being a drama that’s not meant to represent reality, but it’s about a real murder case, all of its major characters are based on real people, and you come out of it feeling as though you’ve just seen an impassioned legal argument: the Celebrity Defense. It’s an exceedingly strange movie. It genuinely seems to believe its title character, cantankerous, spaced-out record producer Spector (Al Pacino), who’s on trial for blowing a woman’s brains out, when he yammers about all of the musical celebrities that lived more sordid lives than he did but were forgiven their transgressions and canonized as pop-culture legends anyway.

Spector is thus transformed into an Ayn Rand hero, the Howard Roark of overdubbing, a genius besieged by parasites; incredibly, the movie doesn’t seem to be kidding. The various women who testified to his misogynist mentality, hot temper, controlling personality, and love of guns during Spector’s first trial are abstracted by being shunted offscreen, the better to let Spector and his defense team (led by Helen Mirren’s Linda Kenny Baden, who represented him in his first murder trial, which ended in a hung jury) tarnish them as gutless nobodies who would never have dared to publicly defame Spector if he weren’t already tarred as a woman-hating killer by the press. (“They came out when it was in their interest to come out!” Spector rails.) And the culture as a whole is depicted as appallingly ungrateful for failing to balance Spector’s personal flaws against his achievements as a record producer and … what? Believe his ridiculous story about the victim, nightclub hostess Lana Clarkson, ending a date with him by sticking a pistol in her mouth and pulling the trigger?

Rather than summarize the elisions and distortions in Mamet’s script, I’ll refer you to this Los Angeles Times piece by Harriet Ryan, who covered both Spector trials. Suffice it to say that the movie presents the defense’s farfetched ballistic arguments as eminently reasonable, and implies that a key witness lied about hearing Spector make an incriminating statement after police coerced him. I wouldn’t mind the fiction/reality disconnect if the movie had bigger aesthetic or rhetorical fish to fry, as Oliver Stone did in JFK or as Kathryn Bigelow did in Zero Dark Thirty, but it just seems weirdly defensive and petulant about Spector’s fate, and its larger argument about celebrities not being able to get fair trials because they’re celebrities is neither novel nor especially engaging.

Mamet has always had a thing for righteous macho martyrs — see Oleanna, about a professor whose pending tenure is scuttled when he is accused of sexual harassment by an ambitious young female student*, and Hoffa, which compared the mobbed-up labor leader to Jesus and wasn’t remotely joking — but now that he’s entered a right-wing troll phase of his career, he’s cranked up the persecuted truth-teller affectation to the point where you can picture Mel Gibson talking him off a ledge. I’m pop-psychoanalyzing Mamet here not because I particularly enjoy it, but because Phil Spector’s tone and thesis are so out-of-nowhere weird that it doesn’t really make sense as anything but an example of an artist projecting himself onto another artist and saying, “I feel you, bro.” There are points in which Spector’s rococo monologues evoke Mamet’s editorial page rants and his books about creativity, cranky rambles in which he often comes across as one of those old rich guys who thinks that being an old rich guy makes him an expert in everything. (Mamet-ologists will recognize Spector’s invective against psychiatry, a hobby horse that Mamet has been riding since 1987’s House of Games: “Freud was essentially, and God bless him, a confidence man,” Pacino’s Spector tells Baden. “He didn’t invent a cure, he invented a disease.”)

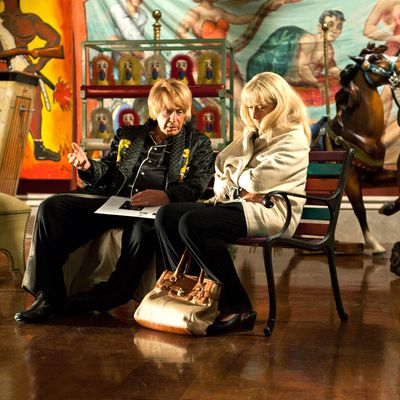

Pacino is predictably outstanding as Spector; he captures the man’s trembling arrogance, which always seemed rooted in childhood fear. It’s such a fully thought-out performance that when Spector shows up for his courtroom appearance wearing a giant blond afro wig that looks like the Death Star by way of Art Garfunkel, it somehow makes sense. Pacino and Mirren’s teamwork keeps Phil Spector watchable even when it’s dousing itself in dramatic ethanol and lighting a match. The script’s notion that Baden and Spector are outcasts who found each other is corny, but the actors sell it so enthusiastically that it rings true and touches the heart — at least until you remember that Clarkson is still dead.

* The description of Oleanna has been corrected.