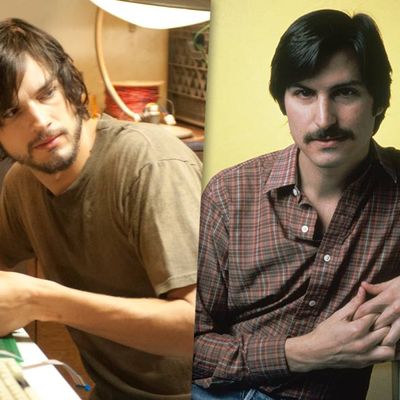

Jobs, the just-released movie about the life and times of the late Apple co-founder, is not a portrait of a nice man. In it, we see Ashton Kutcher’s version of Steve Jobs berate employees, park in handicapped spots, refuse to claim paternity of his child, steal money from his co-founder, cheat his employees out of stock options, deliver a Mamet-like vulgar tirade to a young Bill Gates, and behave in all ways like a world-class asshole, all while fetishizing his accomplishments. (Read Bilge Ebiri’s review here.)

Most of this is strictly accurate. Steve Jobs was a tremendously mercurial person, and he could act like a condescending autocrat when he thought he was in the right. Almost every scene in Jobs is either literally true, or close enough to fool your average moviegoer. But what Jobs fails to get right, for all its adherence to Walter Isaacson’s biography and other Jobs retrospectives, is the mysterious X factor that made Steve Jobs so successful.

The real Steve Jobs was three distinct entities: Genius, Asshole, and Leader. Jobs gets the Genius part right. It shows Jobs at his visionary best — getting Steve Wozniak to see the commercial potential in an all-in-one graphical computer, redesigning the Macintosh to make it look different from every other PC on the market, getting his engineers to pull off near-impossible feats of timing and scale. It also gets the Asshole part right — showing Jobs turning on his friends, snapping at his bosses, screaming bloody murder at everything with a pulse, and having his humanity subsumed into the maw of a fast-growing company.

But when it comes to Leader — the charisma that made people follow Jobs to the ends of the earth and made him capable of world-changing feats — the movie is almost entirely silent. The Jobs of Jobs is without guile, an unlikable psychopath whose management style is all stick, no carrot. For a movie script, this simplistic portrait works well. But it’s entirely different than the real Steve Jobs, whose imperial obsessiveness was tempered by a healthy dose of genuine charisma.

Take the movie’s font scene. At an all-hands meeting, an employee dares to question Jobs’s choice of “adding pretty fonts” on the Lisa computer, the forerunner to the Macintosh, causing Jobs to fire him with a cinematic “Get out!” But this event didn’t actually happen. In reality, Steve Jobs hired a typeface designer, Susan Kare, and got to work convincing the rest of Apple’s executives that fonts were a worthwhile way to spend their money and time. It was an act of soft diplomacy, not a unilateral diktat.

In fact, most of the real Jobs’s big projects at Apple were the result of collaboration and cross-pollination. Many inspired inventions in Apple history — the scrolling wheel on the original iPod and the rainbow-color scheme on the original iMac, for instance — were brought to Jobs by designers at his company who had to convince him of their merits.

He also made it a point to surround himself with smart people capable of challenging him when he made a mistake or pursued a dead-end project. The movie gets enamored of Jony Ive, who would go on to become his lead designer, because Ive gives an impassioned speech telling Jobs how much of a genius he is. In truth, Ive rose through the ranks because he was better than Jobs at product design, and didn’t hesitate to overrule him. The real Jobs had plenty of disagreements, and he didn’t win them all. A notable example of this is when Jobs proposed re-branding the Macintosh as the Bicycle (his theory being that computers were “a bicycle for the mind”), and his team laughed and ignored him. “We simply refused to use the new name,” one of his engineers reportedly said.

The Jobs of Jobs wouldn’t have let that happen. That Jobs surrounds himself with toadies, yes-men, and marks who bend to his will. When he wants the Macintosh to use a faster processor, it happens. When he wants Wozniak and his fellow geeks to fill a purchase order early in Apple’s history, it happens. The only people who truly challenge him successfully are the board members who get him displaced from the company, and even then they’re portrayed as myopic losers. Indeed, the real Jobs’s worst nightmare, the thing he feared most, was a company that accepted his judgments unquestioningly. “In both his personal and his professional life over the years, his inner circle tended to include many more strong people than toadies,” Isaacson wrote. At early Apple, employees working under Jobs even gave out an annual award to the person in the division who stood up to him best.

The takeaway from Jobs is that its subject was both a visionary and insufferable bully, Einstein and Genghis Khan all in one — a crank with a circuit board. But imperious management and pointless nitpickery weren’t how Steve Jobs built the world’s most successful company. He did that through his power of persuasion and an uncanny ability to inspire those around him to take his ideas on as their own passion products, and vice versa. In a way, then, the flaw of Jobs isn’t, as some reviewers have suggested, that it’s too kind to the Jobs legacy — too quick to gloss over his flaws, too hagiographic. It’s actually that it’s not kind enough. By omitting what was genuinely appealing about Jobs, and leaving only his psychopathy and brilliance in place, the filmmakers have turned him into a one-dimensional figure — a Howard Hughes for the microchip age. The real Steve Jobs was a little less crazy, and a lot more human.

Then again, it’s not as if he’d have taken issue with a little theatrical license.