By 1955, the writing careers of Vladimir Nabokov and Dorothy Parker were headed in opposite directions. Parker’s was in a deep slump. The New Yorker—a magazine she had been instrumental in founding—had not published her fiction in fourteen years. Nabokov, by contrast, was becoming a literary sensation. The New Yorker had published several of his short stories as well as chapters of his autobiography Conclusive Evidence and of his novel Pnin. His next novel, Lolita, would bring him worldwide recognition for its virtuosic prose and the shocking story of a middle-aged man’s relationship with his pubescent stepdaughter and her aggressive mother. It was a manuscript that Nabokov circulated very little because he feared the controversy that would erupt when it was published.

Yet three weeks before Lolita arrived in bookstores in France, where it first came out that September, Parker published a story—in The New Yorker, of all places—titled “Lolita,” and it centered on an older man, a teen bride, and her jealous mother. How could this have come to pass?

Nabokov had initially discussed his forthcoming book with his editor at The New Yorker, Katharine White, in 1953. “Don’t forget,” she wrote to him on November 4, “that you promised to let us read the manuscript … Sometimes a chapter or several chapters can be made into separate short stories.” At the end of that year, Nabokov’s wife, Véra, contacted White on his behalf: “He finished his novel yesterday,” Véra wrote to White, “and is bringing two copies, one for you, the other for the publisher. There are some very special reasons why the MS would have to be brought by one of us for there are some things that have to be explained personally.” White and her husband, E.B. White, were away in Maine and missed the delivery, so White suggested that they just mail it to her. But the Nabokovs would not entrust it to the U.S. mail and wanted people who read it to swear to perfect secrecy. “Its subject is such,” Véra explained to White a week or so later, “that V., as a college teacher, cannot very well publish it under his real name … Accordingly, V. has decided to publish the book under an assumed name … It is of the utmost importance to him that his incognito be respected. He would trust you, of course, and Andy [E. B. White] to keep the secret.”

White responded, sounding irked: “I don’t think that Vladimir need worry at all about sending me his book. We manage to keep authors’ anonymity in this way constantly.” The Nabokovs, however, by now were pondering a response from the Viking Press, to which it had been successfully delivered.

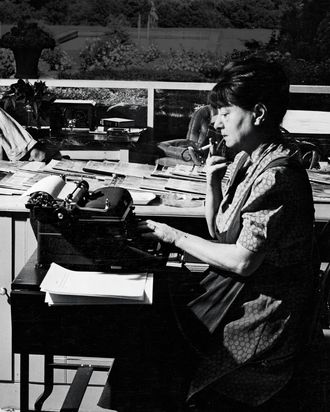

What was Dorothy Parker doing in late 1953? She was living in the Volney Hotel on the Upper East Side, having moved back from Hollywood after her screenwriting career and her marriage had both fallen apart. She was determined to reestablish herself as a playwright and began with The Ladies of the Corridor, a play about aging, lonely women at a hotel like the Volney, written in collaboration with Arnaud d’Usseau. In an interview, she described her characters as “contented women [who] wouldn’t change places with anyone, and if you possibly told any of them they were miserably unhappy, they’d think you were insane. But some of them don’t know they’re dead—that curious death-in-life with which they are content.” The play flopped, closing after 45 performances and mixed reviews. Parker herself seemed to be headed for the death-in-life of the Volney residents she had portrayed.

Meanwhile, Pascal Covici, an editor at Viking, had read Nabokov’s manuscript. In January 1954, he wrote to the author, praising it extensively but calling it unpublishable: “It would be a suicide.” When Véra Nabokov wrote to Katharine White later in January, she enclosed Covici’s letter: “V. wonders if you still will want to see the novel after you have read Covici’s reaction. V. would like you to read it, if only to hear what you think of the possibility of publishing it.”

Katharine White first suggested that the Nabokovs offer it to other publishers. They eventually did, sending it to Simon & Schuster and New Directions. Both declined, but New Directions’ James Laughlin offered that Nabokov might seek out an English-language publisher in France. Nabokov, however, thought he had at least one more American to try: Roger Straus, of Farrar, Straus & Young (later Farrar, Straus & Giroux). Straus had already written to the author himself, misaddressing his letter to “Mr. Nobokov,” and saying: “Our mutual friend, Edmund Wilson, has told me that you have a new novel … Do please send it to me if it’s not committed elsewhere.”

Edmund Wilson was a friend Nabokov shared with many people in American literary circles—including Dorothy Parker. Wilson had first learned about Nabokov’s Lolita in the summer of 1953, when he was contemplating an article about Nabokov and asked the novelist whether he had a new project in the works. “Yes,” Nabokov responded, “I will have … кое что [“something”] published by the fall 1954. I am writing nicely. In an atmosphere of great secrecy, I shall show you—when I return east—an amazing book that will be quite ready by then.” A year later, Nabokov offered to let Wilson read his new novel, which he said he considered “to be my best thing in English.”

In November, while in New York talking to Straus about his own projects, Wilson got the Lolita manuscript and was a bit less discreet than Nabokov would have wanted. He shared it with his current and former wives, Elena Wilson (who “couldn’t put the book down”) and Mary McCarthy (who “didn’t quite finish it”). Wilson further violated Nabokov’s admonition of “great secrecy” by showing it to Jason Epstein, then an editor at Doubleday.

That happened on Thanksgiving weekend of 1954, when Epstein and his wife, Barbara, were at Wilson’s house in Talcottville. As Epstein wrote in his memoir, “Edmund invited me into his study and handed me a manuscript in two black binders. He told me in his high-pitched, rather breathless voice that the author was his friend Volodya Nabokov, that the novel he had handed me was repulsive and could not be published legally, but that I should read it anyway. Perhaps I would disagree.” Epstein was interested enough to ask Nabokov to send him the manuscript, without revealing that he had already read Wilson’s copy.

In January 1955, Parker signed a new fiction contract with The New Yorker and returned to its pages with a story called “I Live on Your Visits.” It too was in familiar aged-Volney-ladies territory. Her next, however, was not.

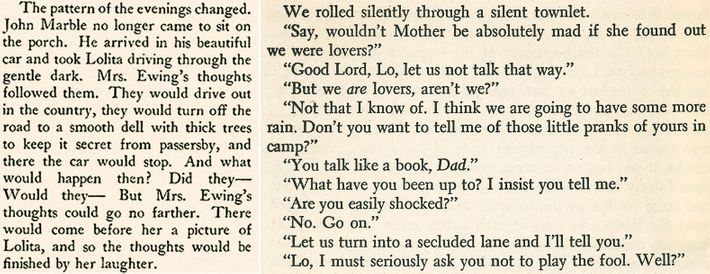

Parker told an interviewer around this time that she usually got the names for her characters from the “telephone book and from the obituary columns.” It is highly unlikely that “Lolita” came from either of those sources. In Parker’s story, Lolita is perhaps 18 or 19 when we meet her, and, unlike Nabokov’s Lo, she isn’t very pretty. But Mrs. Ewing, Lolita’s widowed mother, is—like her counterpart—all about “vivacity,” “sparkling,” and “little spirals of laughter,” not to mention husband-hunting. When John Marble, a dashing man in his thirties and looking “as if he had just alighted from the chariot of the sun,” comes to their town, the hearts of all eligible girls and women are set ablaze, including, we gather, Mrs. Ewing’s. To her mother’s distress, Marble chooses Lolita.

Not only does the story differ markedly from Parker’s other late-career stories, but it is differently written. Parker said she was trying “to do a story that’s purely narrative. I think narrative stories are the best, though my past stories make themselves stories by telling themselves through what people say. I haven’t got a visual mind. I hear things. But I’m not going to do those he-said-she-said things anymore, they’re over, honey, they’re over.” This was, however, just a one-shot deal; she immediately went back to the he-said-she-said model.

By the time Parker’s story was published, Nabokov had been turned down by most American publishers, including Doubleday, where Epstein had failed to convince his boss that they should publish Lolita. (Disgusted, he soon quit.) Following Laughlin’s advice, Nabokov had placed the manuscript with a publisher in Paris—Olympia Press—and it was supposed to be coming out in September. Then, on August 26, he opened his New Yorker, saw Parker’s story, and immediately wrote to another fiction editor, William Maxwell, because he knew Katharine White was away:

Dear Mr. Maxwell,

I am dreadfully upset by the following coincidence. The Olympia Press (headquartered in Paris) are bringing out LOLITA, a novel of mine, on which I have worked for four years and which is scheduled to appear by September the 1st. Before I sold them the book, it had been seen by Viking, New Directions, Straus and Doubleday, and not only by their readers but also by the friends of their readers. There is a story entitled LOLITA in the last issue of The New Yorker by Dorothy Parker.

Please do find out if the term “coincidence” I have used above needs some qualifications; and in any case would you consider my contributing

a note in regard to both Lolitas to your Department of Corrections and Amplification? Or any other appeal, complaint, yelp or distress?

Nabokov, of course, did not believe it was “a coincidence” and put the blame squarely on the shoulders of the publishers and their readers. He also knew about Wilson’s long-term friendship with Parker. After some discussion at The New Yorker, Katharine White, who was still up in Maine, was designated to respond to Nabokov. Her letter on August 31 assumes that Nabokov was blaming her for the leak and for suggesting the name “Lolita” to Parker, and it reads as both disingenuous and defensive. She stated that publishing a clarification would be unwise since the coincidence of two titles—and it was pure coincidence, she assured him—was far from unusual and, in fact, happened all the time. She added that Dorothy Parker was not given to show her stories around or discuss them with her editors until she was ready to submit them. Parker was also, according to White, not the kind of person who would do such a thing. What’s more, Nabokov was lucky, she told him, that his book was coming out soon and so no one would suspect that he took the name from Parker’s story.

The exchange might have escalated into a fight, but when Nabokov’s novel was published two weeks later—under his own name, at the urging of Olympia’s publisher, Maurice Girodias—he found himself in much bigger battles over Lolita. In mid-September, he wrote that he had concluded that the Parker parallel “has no importance whatsoever.” He was still of the opinion, however, that Parker’s “Lolita” had come about “under the possible influence of discussions of my novel, which … were going on at one time, when the MS (most unfortunately) was being passed along among publishers’ readers and their friends.” He could not resist mildly ridiculing the illogicality of White’s suggestion that he might fear being called a plagiarist himself: “My book which is over 400 pages long is built around the name. Nobody could for one moment believe that the title was adopted at the last minute.” (Some critics do, in fact, believe that Nabokov himself borrowed the name from the 1916 German tale “Lolita,” by Heinz von Lichberg. For reasons I have written about elsewhere, I think that one was, in fact, a coincidence.)

As for Dorothy Parker’s “Lolita,” her return to The New Yorker did not revive her career any more than The Ladies of the Corridor had. She soon wrote another play, which was optioned but not produced or published. The New Yorker’s records from 1956 show an “advance of $500 for Dorothy Parker, who is again about to be evicted,” and she sold her old stock in the magazine soon thereafter because she needed cash. But a book review she wrote for the Times in 1957 caught the attention of the editors of Esquire, who were looking for a critic. Among her first assignments was to review Lolita, which had finally been published in the United States by G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

It is hard to fathom how Nabokov must have felt about that, but he could not have been anything but pleased with her review. She commended Putnam’s for its bravery (“And may honors and blessings light upon the heads of G. P. Putnam’s Sons, however many there may be of them”), and then defended the novel itself: “I do not think that Lolita is a filthy book. I cannot regard it as pornography, either sheer, unrestrained, or any other kind.” She praised the author for making the book not just anguished but also “wildly funny” and ended with a tribute to his mastery: “It is in its writing that Mr. Nabokov has made it the work of art that it is … His command of the language is absolute, and his Lolita is a fine book, a distinguished book—all right, then—a great book.”

Had this, in fact, been her second look at the book? The trail, it seems, leads to Edmund Wilson. In 1954 and 1955, Parker was a regular guest at his gatherings at the Algonquin when he was in New York, though his other friends objected to her habit of coming “an hour late” and offering odd excuses, like having to walk her sister’s dog. She is more than likely to have visited him in Talcottville as well, where Wilson had been indiscreet with the manuscript. He would have been very likely to also impress on her his major points about Lolita: that the novel was “repulsive,” that it would never be published in the United States, and that Nabokov was vehement about people not knowing that he was the author. Uninspired, a little desperate, and nearly broke, Parker may have been susceptible to an intriguing prompt. Being Dorothy Parker, she also probably could not resist the opportunity to sting the current “golden boy” of The New Yorker by letting him know that she was aware of his secret.

They would cross literary paths once more, in 1963. Four years before her death, Parker gave up the job at Esquire. The magazine once again needed a book critic and, this time, approached none other than Vladimir Nabokov. “I have given much thought to the highly attractive and flattering offer to take the place of Miss Dorothy Parker whose admiring reader I have been for many years,” Nabokov responded. “Very reluctantly, I must decline it.”

*This article originally appeared in the December 2, 2013 issue of New York Magazine.