“I had maaaaaybe had sex once by that point,” Leo Fitzpatrick says, puffing an American Spirit outside Home Alone 2, the teensy Lower East Side gallery he co-owns with some artist friends. “And it was probably the worst sex you can imagine. And if you think my game was bad before that film …”

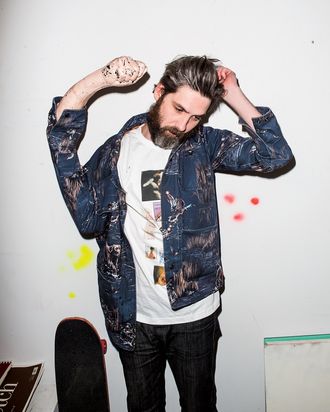

Fitzpatrick is flashing back to 1995’s Kids, the era’s definitive document of fucked-up downtown cool, and the ludicrousness of his casting as Telly, the infamous “virgin surgeon.” He’s 36 now, but clean-shaven, in off-white Chucks and a spiffy jacket dotted with drawings of ducks, he’s still thoroughly boyish. It’s not so hard to envision him as he’s now describing himself: a gawky teenager from West Orange, New Jersey.

Back then, he’d come into the city to hang out with the skateboarders—all “losers,” he says proudly, with “fucked-up families”—in Washington Square Park, which is where the photographer Larry Clark first found him and his friends and cast them in Kids. The movie launched the careers of Harmony Korine, Rosario Dawson, Chloë Sevigny, and Fitzpatrick, whose latest flick, the “preapocalyptic comedy” Doomsdays, is now making the festival circuit.

Not that he’s seen it. When I meet him, he’s sweeping out the gallery, which is currently exhibiting a few spiky John Miller topographic works that look like mountain peaks from Mars. His next show will be a photo exhibition from old friend Larry Clark. “He’s like my big brother or something.” These days, Fitzpatrick explains as we clomp down Forsyth toward his regular spot, Pause Cafe, it’s “the art world I gravitate to more than any other world.” Acting’s just the day job.

“For me, talking about acting’s like talking about accounting,” he says. “Like, ‘Oh, we’re gonna move to this city because all the accountants live there, and we’re gonna work on numbers all day, and it’s gonna be so sick.’ ” When Doomsdays—in which he stars as Bruho, a violence-prone fellow who spends his days ransacking empty off-season vacation homes—played a festival in Denver recently, Fitzpatrick snuck out of the screening to hit up a museum.

For a couple of years after Kids, Fitzpatrick wasn’t so sure he wanted to act at all. At 18, he left for London, where he knew the movie wasn’t out yet, then rambled on to Berlin and Paris. “I had no money,” he says. “I just figured out hustles to get by, like maybe selling my clothes. I wanted to travel around and be broke and live in sketchy apartments.” In foreign cities, he’d always seek out the skaters. There was a “solidarity among the misfits,” Fitzpatrick says. “Now skateboarding’s on TV. If I was 12 years old today, I don’t know if I’d wanna be a skateboarder. I’d probably be into unicycle or something. Anything that wasn’t cool.”

Being a self-identified loser under the glare of microfame was odd enough. That his attention was coming from playing a villain was doubly discomfiting. “I met Roger Ebert at an independent-film awards or something,” he recalls. “And he said, ‘When I saw you just now, I wanted to punch you in the face. And then I had to remember you’re an actor. So congratulations!’ ” Fitzpatrick shrugs. “Those are my accolades.”

He’s carved out a solid career since, pinging between hyperindies and network procedurals and playing Bubbles’s buddy Johnny Weeks on The Wire. The hardest part of acting is “not doing it,” he says. “I wish I could be working every day.” He stays overworked because waiting for the phone to ring with offers would drive him crazy. “My meditation is making shit. The last thing I wanna do is sit home and watch television. Even though I love Pawn Stars and shit.”

At Pause, Fitzpatrick opts for an iced coffee with tons of simple syrup, then gently reminds me to throw a buck into the tip jar. On the bench outside he lights another cigarette, explaining that the coffee and the cigarette are the only constants to his days, which are usually filled with whatever comes up: tending to the gallery; making art with pals (he grew up with photographer Ryan McGinley, and artist Dash Snow was one of his best friends); hanging with his fiancée, designer and D.J. Chrissie Miller; or publishing chapbooks, like the recent Just Born Dead, a collection of journal entries from his twenties, a “bunch of years of sloppiness.”

“My dad gave me my first beer when I was 4 or 5,” he says, “and I fucking have loved it ever since. It’s amazing how much beer you can actually drink in a night.” Remarkably, his vices never went past the brews. “I’m kind of a wimp. I’ve never drank whiskey in my life.” Also: “I once tried to shotgun a beer and poured it all over myself by accident.”

The recent shuttering of Max Fish, his local, has left Fitzpatrick “a man with no land” and has him wondering why he still bothers sticking it out here, where insane rents have hindered the kind of madman creativity that first drew him to the city. “If I was a 16-year-old kid now, I couldn’t afford to move here. I’d probably move to Austin or Detroit. I’m sure there’s a new scene to replace my scene. Everything’s happening in Brooklyn now. I’m not cool enough to know what that is.” He imagines “a life upstate, where it’s a little calmer. You don’t need that much to enjoy life. You know, it’s not like I’m a food blogger. I don’t care about new restaurants.” And then he smiles. “But at the same time, I probably won’t ever leave.”

*This article originally appeared in the December 9, 2013 issue of New York Magazine.