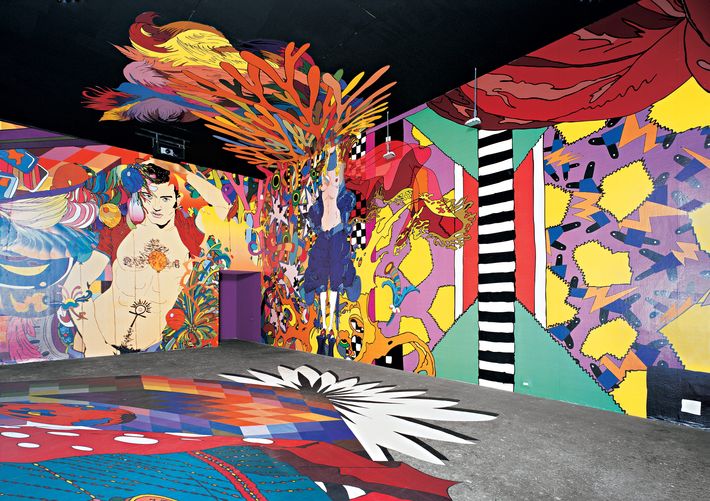

It’s a couple of days into the New Year, and Jeffrey Deitch is in Los Angeles, that city that he, in three years as director of the Museum of Contemporary Art—and like so many swashbuckling, top-of-their-game Manhattanites who moved out West before him—ultimately failed to seduce. His plan was to transform the museum into a House of Deitchism: crowds, excitement, music, dancing, James Franco and Marina Abramovic, graffiti writers mixing it up with Andy Warhol’s soup cans, Kenneth Anger and the sisters of fashion label Rodarte. In short, the entire theatrical, multidisciplinary, occasionally pervy, finger-on-the-pulse aesthetic-entertainment complex that he’d helped stir up in New York, where for four decades he’d cavorted stylishly with a march of boldface names. It was a very New York concoction of cool.

But it didn’t go over so well at MoCA, where his sensationalist instincts rankled those who wanted their art museum to be something more ecclesiastical, set apart from the give-’em-what-they-want box-office mania of Tinseltown. Many in New York had thought his hire was a brilliant one, having seen how Deitch had, apparently out of a simple desire to amuse himself by enabling others, managed to be both transgressive and investment grade all at once. But major museums are not run by big-time art dealers, much less one with a Harvard M.B.A., and while Deitch gave the man who hired him (billionaire collector and MoCA underwriter Eli Broad) what he said he wanted (attention-getting shows, if ones that did disrupt the museum’s traditional educational mission), Deitch didn’t seem that interested in the job of running a museum, with all that glad-handing, fund-raising, and curator petting. He just wanted to be able to do the shows he wanted to do. After much controversy and travail, he announced he was calling it quits six months ago. But even now—as MoCA zeros in on a more conventional replacement and claims it’s raised $100 million for a new endowment—the systematically upbeat Deitch isn’t ready to abandon L.A. entirely.

“It’s 77 and beautiful,” he says from a home he still keeps there, on a day when New York is a grimy tundra bracing for the “polar vortex.” “I find it very productive,” he says of the good-cheer weather. “I’ve already written two essays. So many people I connect with here can live because they sold a pilot two years ago. So it’s much more comfortable.” People in New York, he says, feel embarrassed when confronted by people between projects. “They always ask, ‘What are you doing? When is the book coming out?’ ”

“The book” is a Deitch Projects retrospective, a meticulously curated history and part of a legacy-manicuring project that is Deitch’s Act Three. As I met with him over the fall, Deitch didn’t seem the least defeated by his Los Angeles adventure. Instead, he seemed determined to consolidate his gains and shore up his claim to a central place in the last half-century of American art. I’d seen him first at the Hole, a gallery on the Bowery, where one of his former protégées, Kathy Grayson, let him re-create the eighties nightclub Area, which had been important to him when he was younger (timed to someone else’s book about the place). One of Deitch’s core beliefs is in the dance floor as a cultural teakettle, though he himself is the sober sort, usually in the corner, watching it all go down. He’d filled this party with artwork produced by Area habitués Keith Haring, Chuck Close, and Larry Rivers, and as it got going that night, Deitch took in the dancing, completely naked Japanese-masked young people who call themselves “the Narcissisters” and, half-smile on the face, nodded: “Oh, yeah, we got it. This is Area,” he said quietly. He felt he’d recaptured something, a time when, he told me later, “downtown was really a community, because virtually every artist, art writer, musician, and hanger-on lived somehow in this area.” It was a hothouse he’d been trying to keep alive, or restage, for decades now, as the once-rambunctious city lost a certain energy, first to the devastation of AIDS and then to gentrification.

I later saw him in Miami, during Art Basel, where he staged a talk with his friend Spike Jonze about Her, at which he admitted he “almost had the same kind of relationship with a girl who gives me directions on my GPS.” It seemed like a joke someone else would make about Deitch and his give-nothing-away personal life (almost everyone in the art world is quick to blithely declare him “asexual,” though “Page Six” said he found “true love” with former Warhol crony Paige Powell in 2009). And we met up as well in his former gallery on Grand Street, where he is now both landlord and “guest” of another former protégée, Suzanne Geiss, preparing that monograph on the full fifteen-year life of Deitch Projects, titled Live the Art—a concept, or mandate, that has preoccupied him since the mid-seventies, when he curated his first show, “Lives,” about artists who use their lives as their medium.

It is Deitch, not Larry Gagosian or David Zwirner or Sotheby’s now-ex-capo Tobias Meyer or collector Steve Cohen, who is probably the most exceptional and representative figure of the post-Warhol art world—a strange and slippery amalgam of tight-lipped wallflower and PR-savvy showman. The Greek-Cypriot super-collector Dakis Joannou, whom he’s known and advised since the eighties, jokes that Deitch is “superhuman.” He’s certainly Zelig-like. Deitch claims to be the first person to have bought Basquiat (“five little drawings for $50 each”), midwifed the incredible ascent of Jeff Koons, forged the loss-leader gallery model of supporting exciting and attention-getting but deeply weird work with an aggressive backroom secondary-market hustle, helped give Art Basel Miami its bacchanalian gloss with his annual music-art extravaganzas (Fischerspooner, Devendra Banhart, Santigold, Chicks on Speed), and abetted the process by which the contemporary-art museum became a showcase and playroom for private collections, many of which he helped assemble, in part with work from artists he made stars: Vanessa Beecroft, Cecily Brown, Dan Colen, Shepard Fairey, and Miranda July, among many others.

I’d called him in L.A. to ask about reports that he was about to create a temple to Deitchism in Red Hook. Artforum had blogged that he’d been talking at a holiday cocktail party about opening a “ginormous” new space there, which could be his own mini-MoCA, a monument to his legacy and values without the hassles or compromises. But Deitch says Red Hook is far from a done deal. “I’m looking at different places,” he says, including possibly the so-called SuperPier on the Hudson at 14th Street. “Most of them have complications. I am looking at Red Hook, but there are a lot of issues, like can we get a water taxi going? Who could help subsidize that?” It all came out on the Internet because Russian billionaire Roman Abramovich’s girlfriend, the collector Dasha Zhukova, mentioned that she’d been out to Red Hook (which is already home to many big-time artists’ spaces, including Dustin Yellin and Deitch favorites Urs Fischer and Swoon), and he quizzed her on her perception of its accessibility.

That’s Red Hook, the gloriously isolated former docklands that Robert Moses cut off from the rest of the city with the BQE and then populated with public housing, and that Sandy flooded so badly. Red Hook, which now, like everything else, has become a colonial department of the international art-and-money crowd—a class of people, and aspiration, that Deitch knows well, because he helped create it. “I want to do something big and fresh,” he says. But also: “I do want a space that I can control.”

Deitch knows everyone, but most people don’t know much about him. Like his hero Warhol, he’s an impresario of almost undetectable brio, a painfully painstaking man, patient with his explanations but only because, one suspects he suspects, you might be too inattentive to otherwise understand just what he has in his mind. He is solitary—a disciplined runner, he’s never been married and answers all his own e-mails—and in 1992, he curated a show largely drawn from Joannou’s collection called “Post-Human,” about the blurring of what is real and what is artificial. It’s a concept he can seem to embody: a kind of abstracted and evacuated person, almost holographic, not unlike his friend Jeff Koons. (“I think he has played the role of a post-human character himself,” says Massimiliano Gioni, the New Museum and Venice Biennale curator.) Deitch will talk over people, but politely, unspooling pedagogic insight. That closed-off social affect, for what it’s worth, always annoyed the L.A. Times art critic (and Deitch arch-critic) Christopher Knight, who complained to me that “I’ve sat next to Jeffrey at dinners many times and I’ve never been able to have a conversation with him.”

To talk about his future, and the meaning of his past, Deitch suggested dinner at the Leopard in the old Café des Artistes, near his apartment at the Century on Central Park West. It’s a staid, beige place that lost most of its historical charm in an inattentive renovation a few years back. “So, these are by Howard Chandler Christy,” he says, pointing to the gamboling wood-nymph murals from the twenties and thirties by the artist known for his coquettish World War I recruitment posters as well as Scene at the Signing of the Constitution of the United States, which hangs in the U.S. Capitol. “This is one of the special places in New York City. I wanted this table so you could be inspired here.”

The waitress approaches to take our order: “Do you have good tomatoes today?” he asks, then repeats: “Good tomatoes.” She retreats to the kitchen to check. “I’m very fast,” he says on her return. “What I’d like to get is tomato and mozzarella, please, with extra tomatoes. Then I’ll try the Dover sole.”

Deitch is fastidious and very much in control of his self-presentation: For years, he’s had his trademark glasses custom-made in Germany to his own design, and his trademark double-breasted suits made in Italy by the tailor an old girlfriend introduced him to. “I’ve been through all of these scenes from radical politics and Students for a Democratic Society and the hippie period—all of this, and then punk rock,” he tells me. “But see, I’ve been like the same through it. There’s pictures of me like in the seventies where I look pretty much like I do now, in a way, and that’s part of my thing.”

Deitch was born in 1952 and grew up in Connecticut, where his father ran a heating-oil and coal company and his mother was an economist. He was an exchange student in Japan during high school; his brother imports musical instruments from Africa and Indonesia. “My parents were very cultured people,” he says. “They collected local art. They really were not aware of the New York art world, but the house was filled, still is filled, with art by local artists.” His father’s business had an early computer, and “I took home these reams of this accordion-type computer paper they used to use, and I would just draw endlessly interesting logos and logotypes, corporate logos. Most of what you see is driving around in shopping centers, and you see the signs. It’s on packages. That’s the visual world, so that’s what I reacted to. I don’t know where that art is, reams and reams of my drawings,” he says wistfully. “My mother tried to push me into piano lessons, which I did, but that’s not where my interest or talent was. I remember being an elementary-school student, 8 years old or something, and I remember this vividly, of the first time that I made a serious painting. I was at the beach in Long Island Sound, and I painted the cottage that we were renting. I remember this feeling of ecstasy, of making. I just had such joy.”

It’s easy to see, five decades later in this 61-year-old man, that obsessive kid, drawing logos (the Deitch Projects logo was derived from Warhol’s Brillo boxes). He’s a sort of lonely romantic, a pragmatist seeking a mechanism for transcendent experience—or at least a way to pay for it. “I played in a marching band when I was in school. I played brass instruments. I played trumpet, baritone horn, and I loved it. That was a really fun thing to do. I like that kind of real mainstream Americana, like John Philip Sousa.” (He had a marching band play for Jeff Koons on his 50th birthday and invited the USC Trojan Marching Band to play at MoCA.) “I’m very aware of the connections between art, literature, and music. I look for aesthetic energy, aesthetic movements that are so big that they’re too big to just be an art alone, that they spill over.”

He switched from economics to art history at Wesleyan University—on summer break, he opened a gallery in the parlor of an inn in Lenox, Massachusetts—and also scrutinized Andy Warhol’s Interview magazine, fascinated by the counterculture he created at the Factory. “I just wanted to be part of art, and I didn’t really differentiate so much whether I was going to be a writer, a curator, a dealer, artist.”

What he was looking for was “this kind of aesthetic energy,” he says—he tried his hand at performance art, setting up arguments on the street and then filming them. “I couldn’t get any traction,” he says a little sadly. “Flash Art was the only magazine that covered me.” While working at a gallery, he found the music scene: “Television, Talking Heads, and Devo, and then my favorite, Suicide. It was a great reward to eventually show Alan Suicide’s art at the gallery. I might have been there at the first Talking Heads show in New York. Because I wanted to be able to stay up half the night and go to these concerts, I quit my job at the John Weber Gallery and switched to writing the gallery newsletter so that I could stay out till five in the morning. It was a great education for me.”

But he still wasn’t making money, which is part of why he went and got the M.B.A. “I used to joke that I was the only person who ever went to Harvard Business School and studied art criticism, because I introduced the kind of art writing about the connection between contemporary art and economics. I may have been the first person to write about this. I gave a talk at the College Art Association in 1979 on art and economics. That became, eventually, an essay in Art in America on Andy Warhol as a business artist. So, all that drew on what I learned at Harvard Business School, understanding economics and the theory of marketing. So, it really helped me to have an original take on art and its economic structure and the way the art market was a crucial part of the consensus of how artists present their work to the world and how they’re judged. I wrote up a business plan for a bank to start an art-market department, and I went to both Chase and Citibank, but in 1979, Citibank was the more dynamic bank. Walter Wriston was chairman of the bank, who went to Wesleyan, where I went to school. He was a legendary, visionary business leader. So, I decided to go to Citibank.” The slope-roofed new headquarters had just opened (“I just noticed there’s a Haring work that’s up for auction of a flying saucer zapping the Citicorp Center”), and Deitch got to go to Japan a lot, because Japan was buying a good deal of art with all the extra money from what became known after the fact as its real-estate “bubble economy.” He finally got to know Warhol through an advisory gig he had with something called the I Club in Hong Kong in 1982—“a similar idea as Area, but it was a heavy investment,” he says (meaning a reported $10,000 membership fees). Warhol had done a portrait show at the Whitney, “and I knew Andy loved going around, getting portrait commissions. So, I brought Andy Warhol to Hong Kong.

“Before, I’d seen him around. When I visited the Factory, I did this research on business art, and he would just talk in monosyllables. I just figured he doesn’t really talk in complete sentences. Then I picked him up at the airport in the Mandarin Hotel Rolls-Royce, and he’s very energetic. He and his entourage booked the whole first-class section on the Pan-Am flight. So, he was ready to go and go to the club and have dinner, and there’s this big Chinese-style table with a lazy Susan, and it was Andy’s entourage and me and Alfred, the owner of the club. And Andy was comfortable with all of his friends, just talking. I just couldn’t believe my ears. When I came back, talking to [gallerist] Leo Castelli, I said, ‘Not only does Andy talk, he’s one of the most fascinating conversationalists I’ve ever encountered.’ Leo said, ‘Of course. Who do you know who has a more interesting life than Andy Warhol?’ ” But most of the time Warhol kept that voluble self under wraps, Deitch says, “because he couldn’t talk to all these people wanting to hustle him into this or that.”

In 1988, Deitch started his own art-advisory firm—both living and working in Trump Tower, an easy stroll every Friday over to MoMA to study the collection. But “in the eighties and in the nineties, I was feeling unfulfilled,” he says—still a little too far from the curatorial center of things as merely an art businessman. “That’s one of the reasons why I did Deitch Projects. I had to get into more creative things.” He’d sell an $8 million Warhol and bankroll a performance collective like Fischerspooner—he’d do that kind of thing quite a lot. “The business was never an end in itself; it still is not,” he says. “One of my roles is to be the kind of person who finds money for the most transgressive, crazy art project, to make it happen.”

“He very clearly crafted his image around being this agent-provocateur citizen of the world,” says painter Kehinde Wiley, who had his first New York solo show at Deitch Projects when he was just out of Yale art school. (“In studio visits he would never have negative criticisms. He would say, ‘I like this, this is a masterpiece.’ ”) “He reminds me very much of the flâneur: He’s in society and not engaging. But there’s a fork in the road where the flâneur is able to take all that knowledge and mobilize it, but never is it about personal agency. Sort of like the Wizard of Oz.”

“The criticism that he gets sometimes is that he’s critic and curator and finance expert,” says Gioni. “Sometimes he is criticized for being complicit with the market. But he became his own model.” The other criticism, of course, was that he wasn’t actually serious about serious art—or not as serious as he was about the party taking place around it. Which he sort of confesses to: “I do not think that there’s any contradiction between being rigorous, super-serious, and being fun and lively,” he says. “Look at the greatest artists, Picasso. This is the most rigorous, toughest stuff. He pushed and challenged himself, but you see the images of Picasso—he’s having fun, he loves it. Toulouse-Lautrec, this is revolutionary, rigorous art. He’s hanging out in those clubs. He’s going to the Moulin Rouge and having a good time. Of course, obviously, the example of Andy Warhol, the Factory. That’s a fundamental thing, that there’s no contradiction between engagement and enjoying life, and a rigorous approach and disciplined approach to art, and you should be able to do both. Art that’s deadly serious—and some that I respect—it’s not the art that excites me.”

But in 2010, he chose to shut down his Emerald City carnival of the new, as well as the art-dealing operation he’d honed to pay for it, to become the director of the financially troubled MoCA at the behest of Broad, with whom he’d worked quite closely over the years and who would call Deitch’s arrival a “game changer.” “I feel as if I’ve been training for this position my entire life,” Deitch said at the time.

Reinventing the museum would be Deitch’s biggest project yet: his high-low show on a big new soundstage and with better weather. But running an institution was a very different game. As a gallerist, “you can indulge completely your own interests,” says Christopher Knight. “A really great museum director has to have the capacity to set aside his aesthetic biases and support the staff.” Instead of Deitch Projects’ two garagelike galleries in Soho (and satellite spaces in Brooklyn and Long Island City), he’d have an entire museum, and in some ways an entire new city, at his disposal, not to mention an 8,000-square-foot house, with space to display his cheerily surreal art collection (there’s a Michel Gondry piano that plays a video programmed by participants in 88 locations around the world). In New York, he’d bunked in a monkish apartment near Central Park, where he’d run miles every morning; at his place in L.A., he could have a hundred people over. It’s up near Griffith Park, looking down on the city and up to the Hollywood sign. For added transgressive romance—which is what seems to make Deitch most happy—it’s said to be where Cary Grant lived with Randolph Scott.

“I got so slammed for this show,” says Deitch, shaking his head in disbelief. It’s the day before Thanksgiving, and we’re looking at images of Dennis Hopper’s art, the subject of a MoCA show that opened a few months after Deitch arrived. “Did you know his photographs? They’re great.”

When in New York, Deitch has set up camp at 76 Grand—he still owns the building, though Geiss has been running her gallery in it. And now they’re sharing the loftlike upstairs office again, with matching desks that look like they come from a Sol LeWitt home-furnishings line. “Suzanne,” Deitch says, looking over at Geiss, a stylish woman in an interesting sweater with three tasteful rings in her left ear, who’s winding up business so she can go away for the weekend at Disney World. (No, no kids, she tells me, just because she loves Disney World.) “You saw ‘Hopper,’ right?”

“Yeah, I went out for it,” she confirms, one hand on her phone.

Deitch turns back to his computer screen. “It was just crazy … You’ve read all this negative stuff from New York critics who never went there, who didn’t understand that this was … this was as interesting as anything that any contemporary museum in the country did, what I did in three years …” To prove it, he’s doing a book about his time there, too, called The MoCA Index.

Rain drums on the skylight, trucks rumble down Grand, and two other well-turned-out young women toil away on the other side of the bright-white room in front of a wall of bookcases, one with a small sculpture on her desk of a hand, middle finger up. Deitch stops himself: He is not by nature a grouser, or a glum and persecuted outsider, but rather a thoroughgoing, almost aerobic optimist, a man whose fundamental talent might be the consistency of his affirmation of whatever strikes his conceptual fancy. Which is a lot.

He turns to the PDF of Live the Art, to be published in the fall by Rizzoli. It’s a kind of art-history memoir, told as a visual essay; a dinner plate will be fused to its cover. Its first line is “Deitch Projects was not meant to be an art gallery.”

“I’m really privileged and inside the center of the art world, since the early seventies,” he says. “I absorbed so much and am lucky to have had personal relationships with most of the major artists, all of the major artists, most of the major collectors, dealers, and curators. I want to do what I can to solidify this knowledge and to participate in the writing of the history,” he adds solemnly, gently. “It doesn’t mean I’m not interested in the new stuff anymore. I still am, but I feel this responsibility that I can’t just let this all go through my fingers. I want to be part of telling this story.”

We turn back to the book, and he begins to tell the story: “Joe Fawbush had this gallery, and it was a very good gallery,” representing Kiki Smith and Christian Marclay. This is where we are now, 76 Grand, at one time the home of a workshop that made theater curtains. “He died of AIDS. His partner, Tom, knew that I loved the building. They were good friends. He asked me if I wanted to take over the lease. I made a deal with the landlord to rent with an option to buy, which was a good deal you could make in those days.” At the time, he was helping Koons create his “Celebration” series (which reportedly nearly bankrupted Deitch), and 76 Grand “was a project room just to have fun while I did my art-advisory business.” In the beginning, he invited only artists who hadn’t yet had a New York solo show and would give them $25,000 in production funds, which, if not reimbursed through sales, meant that Deitch got to keep the works for his own collection.

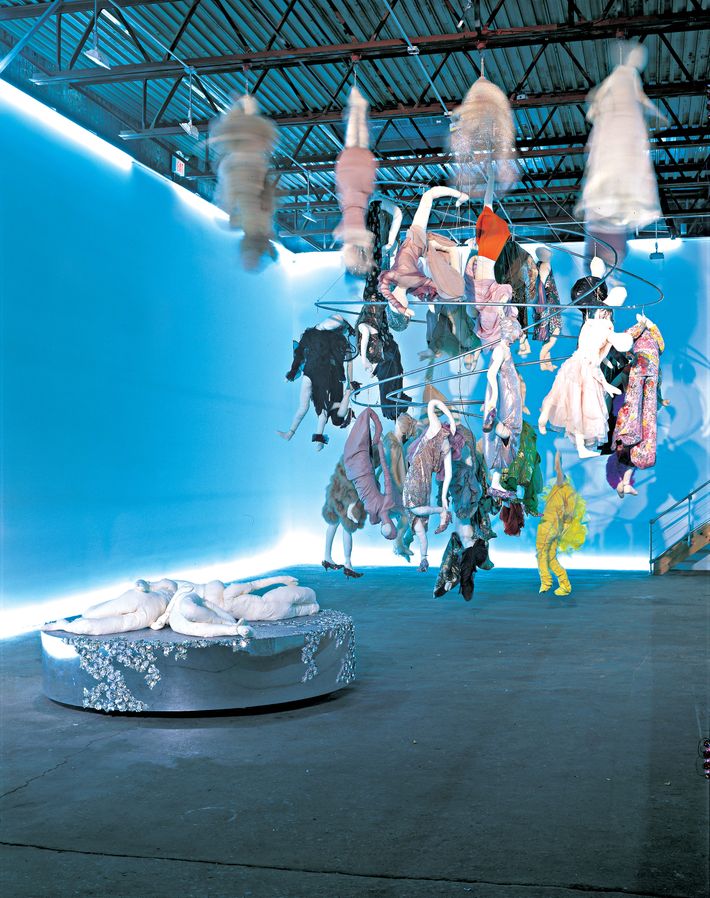

We scroll on. There’s Vanessa Beecroft, who filled the room with twenty nearly naked women. There’s Jocelyn Taylor, walking fully naked down Canal Street. There’s Russian artist Oleg Kulik, who lived for two weeks as a dog. “He just was incredibly brilliant, in fact really scary. You believed that he was a dog,” Deitch says. This was fun; soon he bought the building housing Canal Lumber, a bigger space around the corner on Wooster. The first major exhibition project there was of a Barbara Kruger video-and-slide-projection show in the fall of 1997.

There was Shower in the Dark, a conceptual performance from 2002 where participants were asked to leave their underpants in a cup when they departed and got a Deitch Projects thong in exchange. There was Paul McCarthy’s The Garden (featuring an animatronic man humping a tree). There was “Session the Bowl,” in which he turned the Canal Lumber space over to skateboarders. “This is a crazy thing we did with Patricia Cronin,” he says, turning to a sculpture of two women in bed. “She wanted to have a show here. I said, ‘I’ve got a better idea. It shouldn’t be a show in a gallery. Let’s buy a cemetery plot.’ She said, ‘Well, I want a gallery show.’ ‘Trust me,’ I said. ‘This is much more interesting. It’s permanent.’ ” It’s a grave site for her and her partner in Woodlawn Cemetery. “It’s really transgressive to have in a cemetery. And this is now like one of the major stops on the Woodlawn Cemetery tour, with Miles Davis’s grave.”

He goes on and on: “Isn’t that crazy? This is amazing. This was a good show … And this was another phenomenal show. This won the Critics’ Prize that year for best show … This is probably our most notorious show … A thousand people at this opening.” We get to the “Art Parade,” which took over the nearby blocks with a street party. “There are all these people coming to us with great projects, and I said, ‘I’m sorry, there’s no slot for you.’ So the ‘Art Parade’ was an opportunity to say, ‘Everybody, you can come.’

“I’m very idealistic,” he says. “I just have this fundamental idea that vanguard art can be life-enhancing and can be inspiring to all kinds of people. I don’t have a hierarchy. For some people, if you’re a kind of conventional person with a job and money, then you’re evil. Or, for others, people who live that kind of conventional life, people who are on the margins, whether culturally or economically, they are like subhuman. You don’t want to go near them. I try to be open, embracing, with everybody, and I want everybody to share in the exhibitions if they decide to. Today, I was in the office of maybe the most important real-estate person in the country, talking about an art project, and tonight I’m having dinner with Alan Suicide. So that’s been my life for a long time.”

He pauses. “It was a great experience at the museum, but I had a much more efficient system,” he says. “I’m happy to be back doing it my way.”

*This article originally appeared in the January 20, 2014 issue of New York Magazine.